The Eye of Providence gazes at us all.

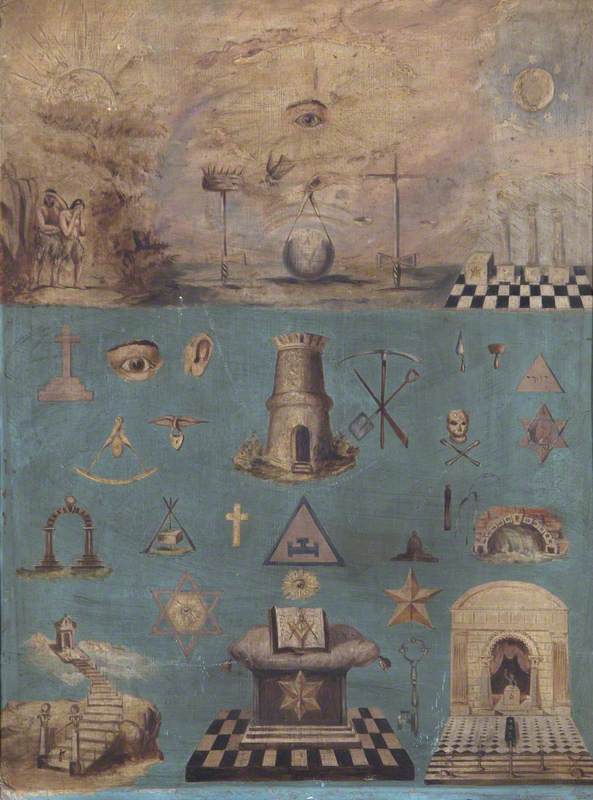

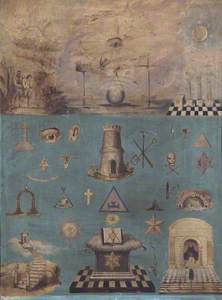

In Masonic Symbols, the 'Eye' hangs above a cryptic collection of pictures: a visual encyclopedia for new Masonic members to learn the hidden language of one of the oldest craft guild organisations in the world. The eye is a symbol that – to Masons – represents God, or the Great Architect of the Universe, but others may recognise the watchful oculus from other places – Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Mormon churches, university and fraternity coats of arms, and even on the back of the American dollar bill seated within the Great Seal of the United States. It is usually surrounded by a triangle, its sides representing the three persons of the Trinity.

A relief of the Eye of Providence on the north gable of the chapels at Flaybrick Memorial Gardens

But the 'Eye' itself is much older than the organisation that uses it in the painting above, dating back to Greco-Roman depictions of a watchful Christian God; the symbol itself was also used in alchemy, astrology and Rosicrucianism. The eye is just one example of a Freemason symbol that communicates messages only understood by fellow Freemasons. Thus, one of the most secretive brotherhoods in English history hides pieces of itself in plain sight.

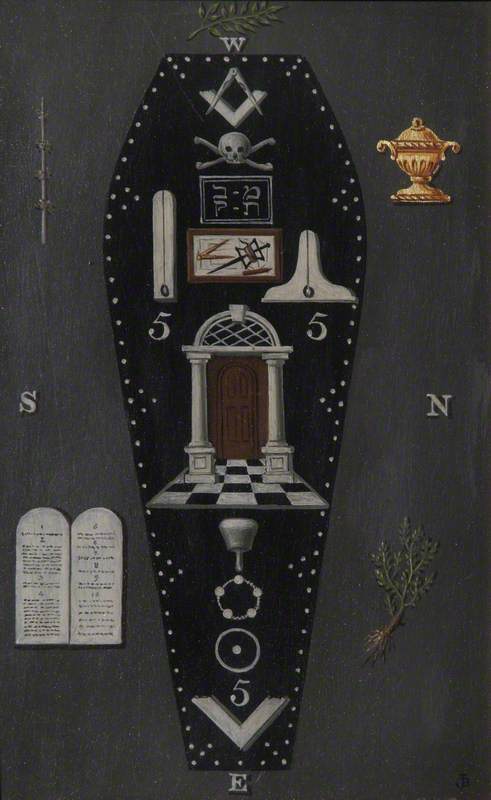

This first painting above, Masonic Symbols, is rife with emblems, from the all-seeing eye, three columns, a black-and-white chequered floor, mortar and pestle, winding staircase – all explored below – and one of the most recognisably Masonic symbols: the square and compass. The square is closely associated with morality, or acting within the square of virtue, and the compass refers to a Freemason conducting themselves within the boundaries of their trade, lodge and society. They are key measuring tools that remind Freemasons to remain within lodge- and society-dictated conventions.

Many Masons recognise English Freemasonry to have started in 1717 when the Grand Lodge was founded in England; bookseller Anthony Sayer served as the first Grand Master of the Lodge. However, the diary of astrologist and antiquarian Elias Ashmole documents the earliest Freemasonry activity in England. In 1646, he recorded that he had been made a Freemason at a lodge in Warrington, later documenting a lodge meeting at Cheapside in the City of London in 1682.

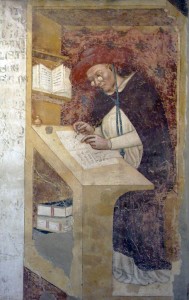

Some Freemasons trace their lineage even farther back to Medieval stonemason guilds that constructed cathedrals towering into the clouds. Some argue that the Freemasons were a sect of the Knights Templars, a Medieval Catholic militant organisation. Some even believe that Freemasonry and the Illuminati, an eighteenth-century German society, are one and the same. Some Freemasons, however, argue that their organisation dates back even further to the builders of the Biblical Solomon's Temple.

The Temple of Solomon, also called the First Temple, is believed to have existed between the tenth and sixth centuries before Jesus's Biblical birth. The Old Testament states that King Solomon proclaimed this temple a fulfillment of God's promise to David, to serve as a place of worship and assembly for the Israelites. Stonemasons were key builders of the temple and were saddled with a divine mission. Aspiring stonemasons often apprenticed with experienced craftspeople, and in the Medieval period, when stonemasons were in great demand, stonemasons founded guilds to protect their wages and regulate who could teach apprentices, who could become one and the quality of their work.

The guild apprenticeships cloaked the Masonic guilds they created in secrecy. While the guilds broke down in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the social lodges remained, often marketing their exclusivity to people of wealth and high social status. Because of their proprietary craft, Freemasons used hand gestures, handshakes, or verbal or visual passwords to identify Masons from non-Masons. But with this secrecy came exclusion. While the first Parisian Masonic lodges welcomed Black and white clergymen, women and traders, English and American Freemasons prohibited their membership.

At the same time, this Biblical lineage reinforced their spiritual and economic 'birthright' and connects modern Masons with a Biblical divine mission. Some scholars and Freemasons argue that their organisation is a secular movement – the altars in their temples holding the holy books for all members – but Freemasons' emphasis on brotherhood under God complicates the picture. In truth, religion and Freemasonry have a complicated relationship.

The Mystery of Masonry Brought to Light by the Gormagons

1724, etching & engraving by William Hogarth (1697–1764), reissue published by Robert Sayer (1725–1794). The figure with his head through a ladder could be James Anderson

While the religious imagery and rituals highlighted in these paintings recall orthodox churches, Scottish Presbyterian minister and Mason James Anderson argued in his 1723 constitution that deism – or the belief that God created the universe but remains uninvolved as the Supreme Creator – frees people from orthodoxy and dogmatism. Deism, he argued, also reinforced tolerance, a key principle for Freemasonry in word but sometimes not in practice. Guiliano Di Bernardo argues that Freemasonry's connection with deism in England, France and the United States facilitated its spread around the world. Deism was also practised by many leaders of the Enlightenment: the intellectual movement that bled into Freemasonry.

Pannill Camp challenges the overarching idea, however, that Freemasonry, Enlightenment philosophy and deism fed into one another, highlighting how ritual remained a key part of the Masonic 'craft'. In fact, Freemasonry's association with deism caused rifts in England where Masonic leaders saw deism as conflicting with older Masonic traditions. This conflict led to the creation of the Ancient Grand Lodge of England. Similarly, the Catholic Church criticised Freemasonry for centuries, associating its secretive rituals with the occult and paganism. The Vatican went so far as to prohibit Catholics from becoming Masons in 1738.

Perhaps this indicates that Freemasonry is its own religion, Roman Catholic author William Whalen argues – one that aligns itself with naturalism, but this argument also conflates deism with pagan practice.

This scene of Mary presenting Jesus to a religious brother, possibly a friar, was painted on the back of a Masonic engraved copper printing plate.

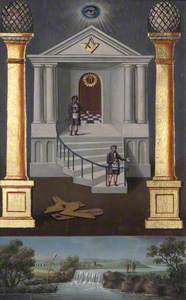

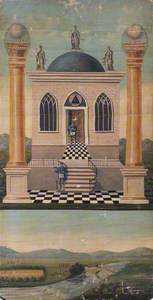

Whether or not Freemasonry is its own religion, the iconography frequently used in Masonic art highlights how the movement borrows symbols from various Christian communities. Only Masons formerly knew the meaning of these symbols – indicators of a secret order during a time when Masonry was prohibited – and they were thus employed in rituals to educate new members. The best examples are tracing boards, used as visual aids during Freemason initiation rituals. There are three different types of tracing boards associated with three different ceremonies.

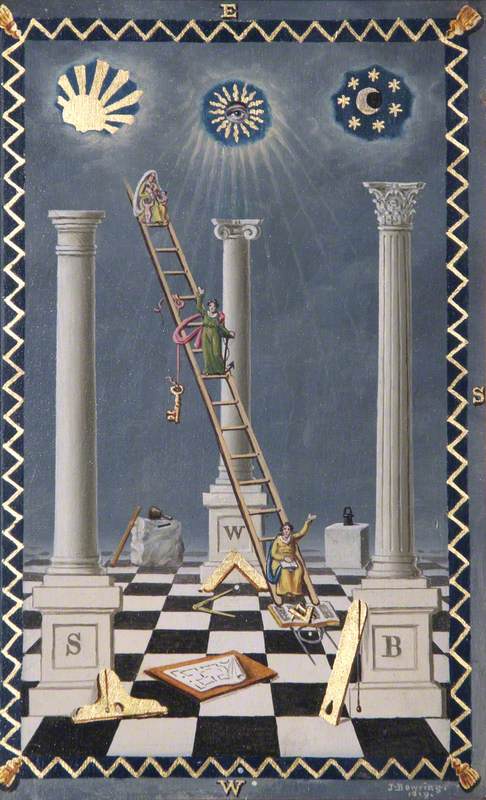

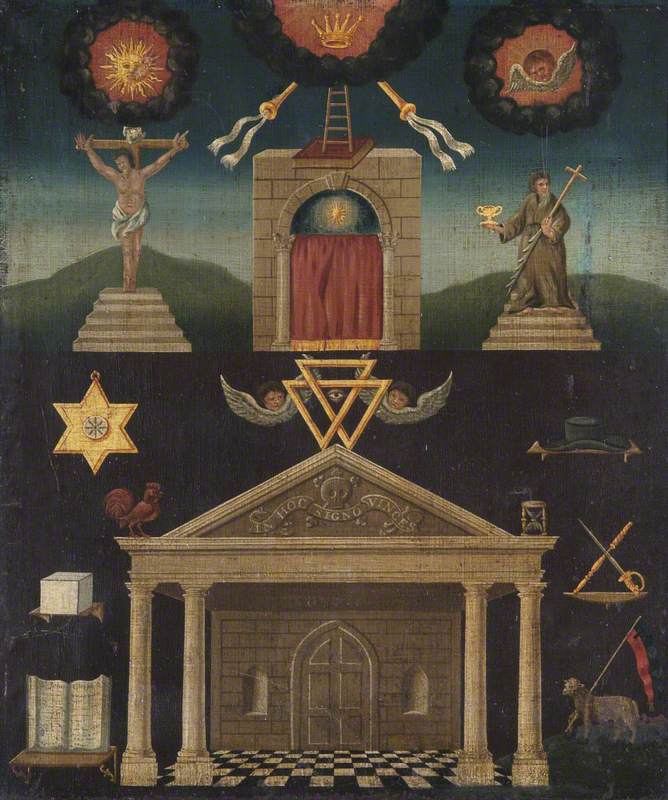

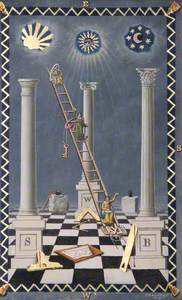

The first tracing board is the apprentices' first introduction to Masonic symbolism. Underneath a sun and moon – prophetic symbols representing God or their dominion over nature – Bowring highlights three types of classical architecture. The three types are highlighted by Doric, Ionic and Corinthian columns. Just as the sun and moon also serve as emblems of Masonic leaders, so too the columns represent key Masonic roles.

The Corinthian columns stand for the Master or Ruler of the lodge and his two deputies or wardens. The letters and symbols at the base of the columns represent their attributes and emblems: 'the Master's wisdom and set square, the Senior Warden's strength and level and the Junior Warden's beauty and plumb rule.'

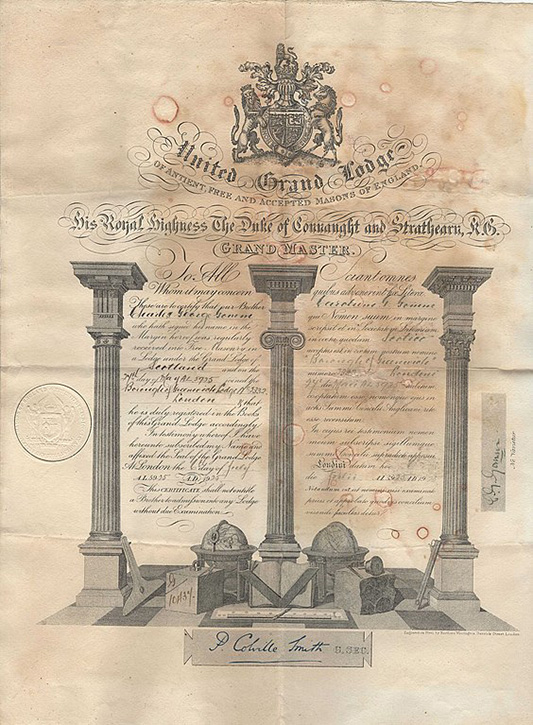

A registration certificate with the three Corinthian columns

In the book of the United Grand Lodge of England, 1925

Take note of the black-and-white flooring: a key feature of Masonic lodges. All new members are initiated on the black-and-white stone floor, whose colours represent the good and evil of human life. During the first degree ceremony, the floor represents the ground-level floor of Solomon's Temple, where all apprentices start their journey in the Masonic lodge and wider organisation. Further, the black-and-white squares refer to the duality of the human body and human action.

Also in this painting is Jacob's ladder, referring to when Jacob dreamed in Genesis that he saw a ladder stretching from Earth to heaven, with angels climbing up and down its rungs. In Freemasonry, the central rungs of this ladder represent faith, hope and charity; the others temperance, fortitude, prudence and justice.

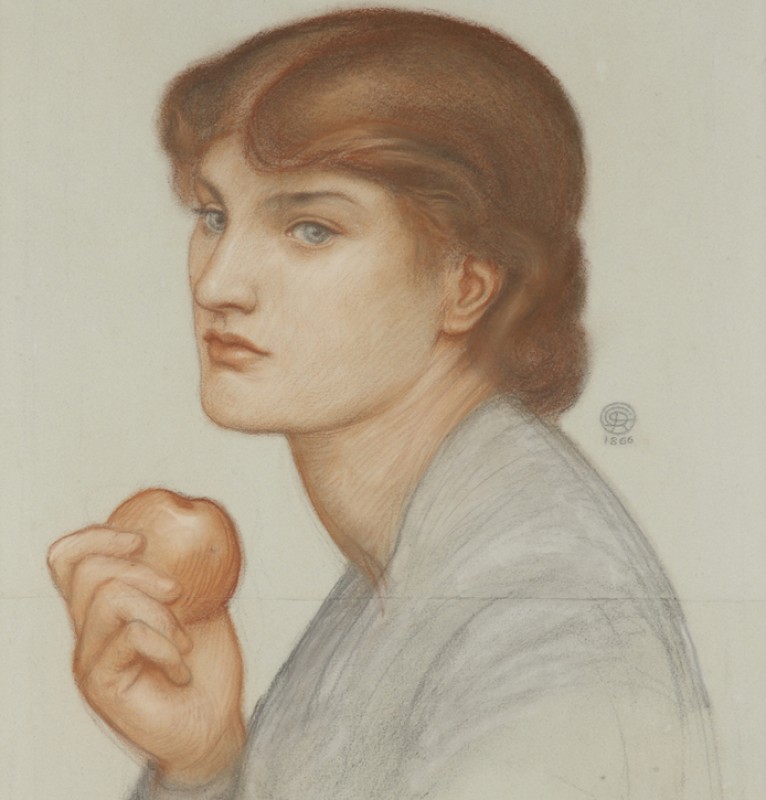

Another painting titled Faith, Hope and Charity personifies the three virtues. Faith and Hope stand or sit on either side of a temple with Masonic emblems (such as a square and compass) carrying a cross and anchor. Above them hovers Charity and an all-seeing eye.

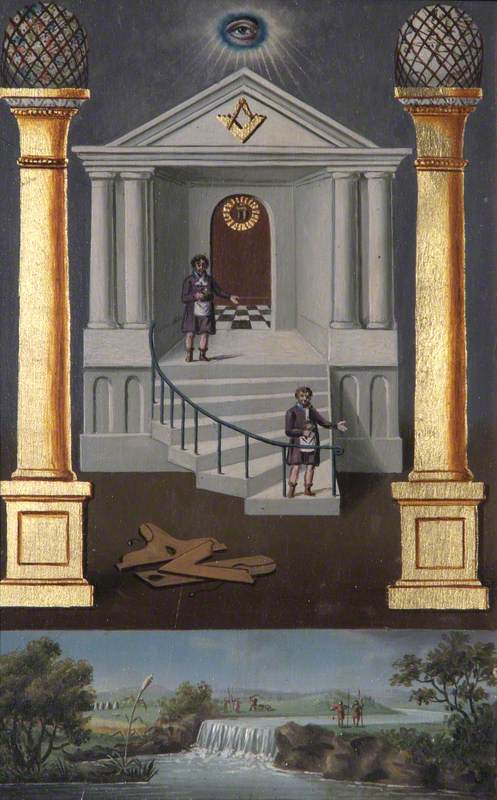

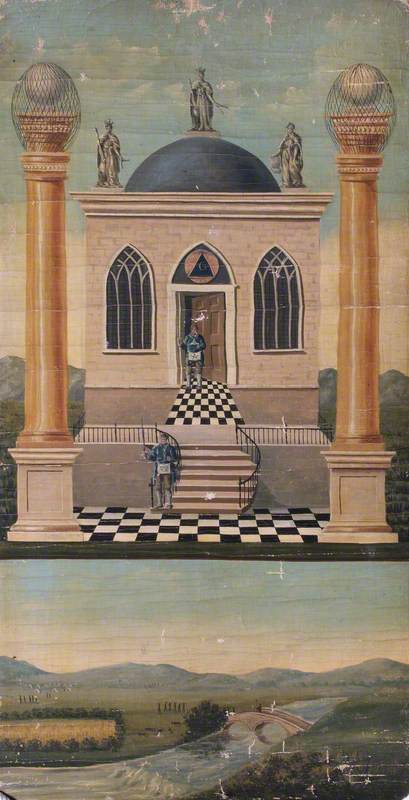

In Bowring's Second Degree Tracing Board, the ladder is replaced by a winding staircase. These stairs represent the steps leading to the middle chamber of King Solomon's Temple and an apprentice's progress throughout the organisation. Two Freemasons are shown, one on the first step and one on the top. Masonic initiation even includes a reenactment of a scene involving the Temple while it was under construction, and a Masonic lodge symbolically becomes the Temple when it includes ritual objects like the two copper, brass, or possibly bronze pillars – identified as Boaz and Jachin – on either side of Solomon's Temple. Similar bronze pillars appear in second degree tracing boards made in 1810 and 1832, this time continuing the chequered flooring.

The third ceremony reinforces the mortality of humans, so the tracing board is overwhelmed by a coffin. These ceremonies would symbolically use stonemason's tools – represented in Bowring's 1819 Third Degree Tracing Board by the set square, level, plumb rule, maul and compass – but also incorporate religious imagery including the stone Ten Commandments.

The ceremonies may also include a skull and crossbones, referencing memento mori or the Catholic concept of surrounding oneself with evidence of death as reminders of mortality. Bowring's 1810 Third Degree Tracing Board even features an open casket with a deceased individual laid inside.

The third degree tracing board also features the plumb and level, which stonemasons use to ensure surfaces are level and vertically flush. Today, the tools of the trade symbolise justice and moral verticality, or acting in an upright manner. They also represent that all people are equal, although this was not always the case among Masonic lodges, as highlighted above. These symbols appear alongside a trowel in the first Masonic Symbols painting, which is employed to spread the mortar that holds stones together. Among Freemasons, this symbol refers to spreading the 'cement' or glue of brotherly love that binds Freemasons together.

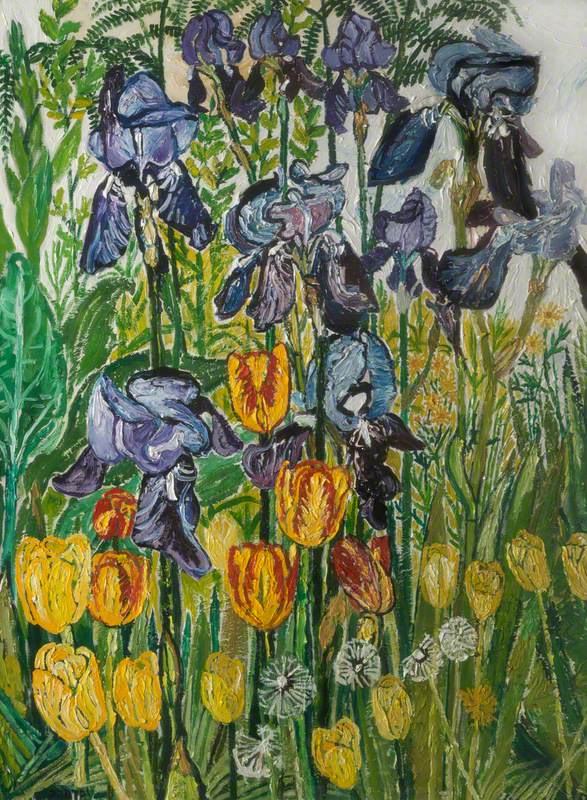

Some third degree tracing boards also feature a sprig of acacia. seen in Bowring's 1819 Third Degree Tracing Board above. The acacia plant, native to the Middle East, can regenerate from a seemingly dead branch and thus represents the promise of immortality and the afterlife, specifically salvation through Jesus and a Christian God.

Masonic Symbols below features a cockerel, representing the animal that crowed three times when Saint Peter – one of Jesus's trusted apostles – betrayed him before his crucifixion. Crucifixion imagery continues throughout the painting with a crucified Christ in the upper left and Saint Peter on the upper right. Most interesting, however, is a lamb carrying a flag in the lower-right corner.

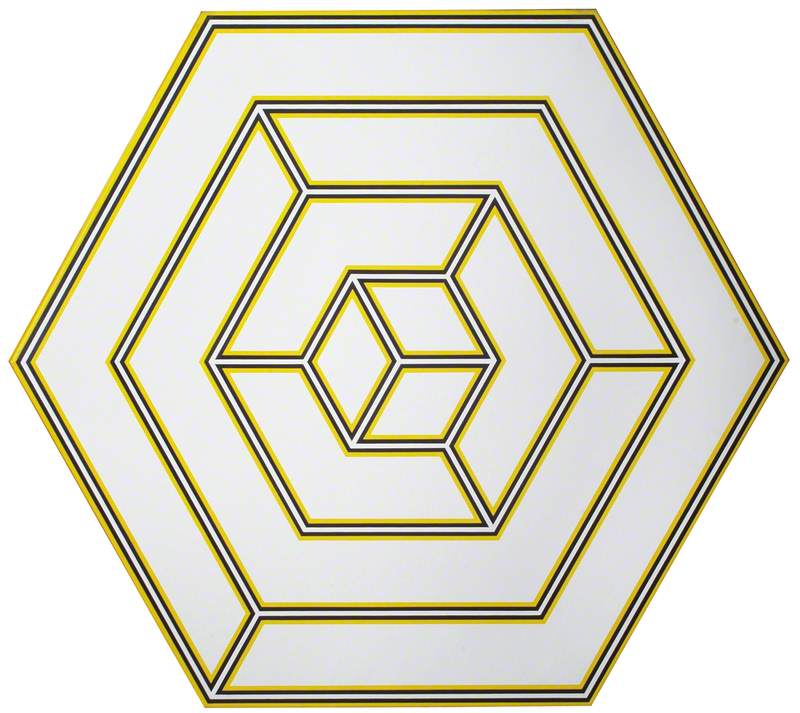

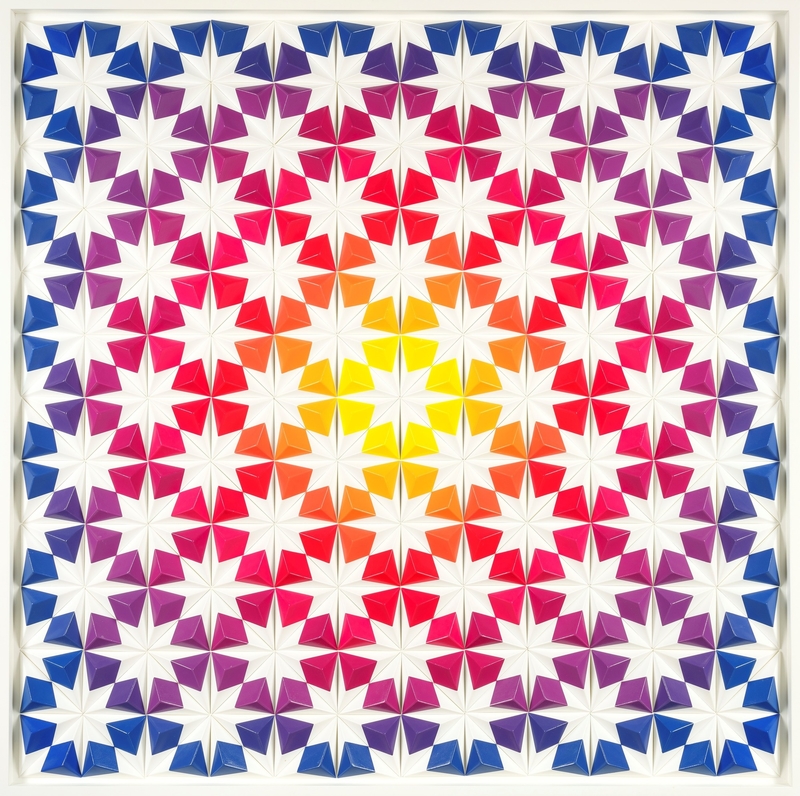

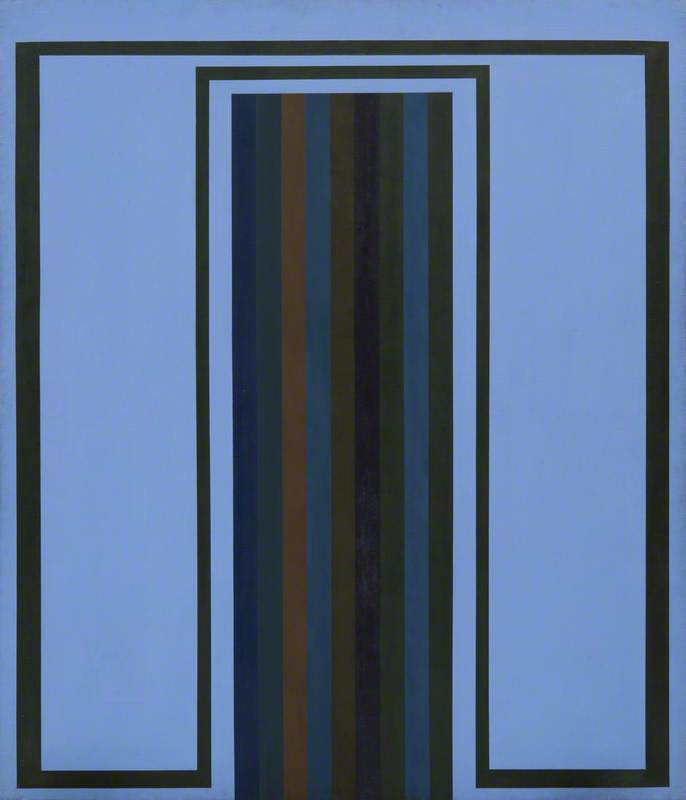

This lamb allegorically refers to Jesus being killed for humanity's sin and also parables in which he describes himself as a diligent shepherd of his flock. Masons even ceremonially receive a white lambskin apron during their initiation, setting themself apart with the appearance of an apron that represents purity, honour and affiliation with other Masons. Take another look at the second degree tracing boards above and spot the men standing on the winding staircase wearing white lambskin aprons. This deeper meaning surrounding the colour white is also highlighted in the geometric painting Perfect Ashlar (1972), where it represents purity and innocence.

But this symbolism goes even deeper with the Feast of the Paschal Lamb, also called the Ceremony of Remembrance and Renewal or the Mystical Banquet. This feast is a ritual welcoming in the spring. In this ceremony, Masons break bread together in honour of their brotherhood and in memory of brothers who have died. Although the Feast recognises Passover and Easter through its symbolism, it is traditionally held on Maundy Thursday – the Thursday immediately preceding Good Friday, or the day Christians believe Jesus was crucified.

As the Scottish Rite shared in a blog explaining the ritual, the Feast of the Paschal Lamb serves 'as a reminder to Brothers that our lives are to be dedicated to the Masonic principles of duty and service to elevate mankind.' Conflating the spread of Masonic knowledge with the elevation of humanity is one element that highlights a darker side of Freemasonry. In the painting O Wonderful Masons, a stonemason watches with his tools – a square and compass, gavel and chisel – as women fly across the sky from the darker Stonehenge on the right to London on the left.

The painting is strikingly similar to another, deeply problematic one – John Gast's American Progress. In this painting, a woman too flies across the sky but from the brighter, right side with railroads and farms, to the darker left side, where Native Americans flee settlers.

American Progress

1872, oil on canvas by John Gast (1842–1896)

While O Wonderful Masons is not as explicitly racist and imperialist as Gast's painting, it does showcase how religious symbolism in Freemasonry reinforced their power as bearers of intellectual and architectural progress but also how Masonry was a key part and weapon of colonialism, especially among early leaders of the United States. Taking a closer look at these decorative and functionally educational paintings allows us to spot many hidden symbols that continue to hold social and spiritual weight today, and symbols that continue to be used to further exclusionary (or inclusionary) ends.

Emma Cieslik, religious scholar, museum professional and writer