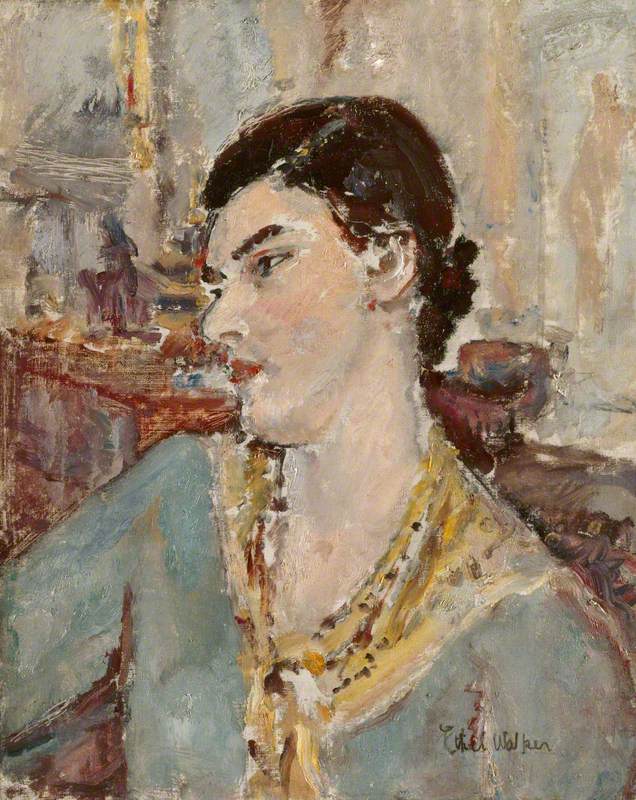

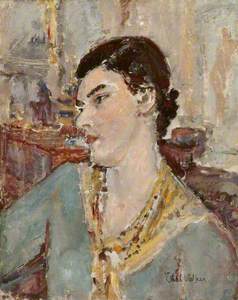

Although she is a presence in many museum collections in Britain and was celebrated in her lifetime (taking part in the Venice Biennale four times, becoming the first woman member of the new English Art Club and Associate of the Royal Academy, and being made a CBE and Dame), Ethel Walker (1861–1951) is little known today.

That she remained resolutely figurative – despite the avant-garde push to abstraction which has dominated accounts of the art of her era – did not help, but there was also the fact that she was a woman painter predominately of women, and also a lesbian, therefore doubly vulnerable to discrimination present in mainstream art history.

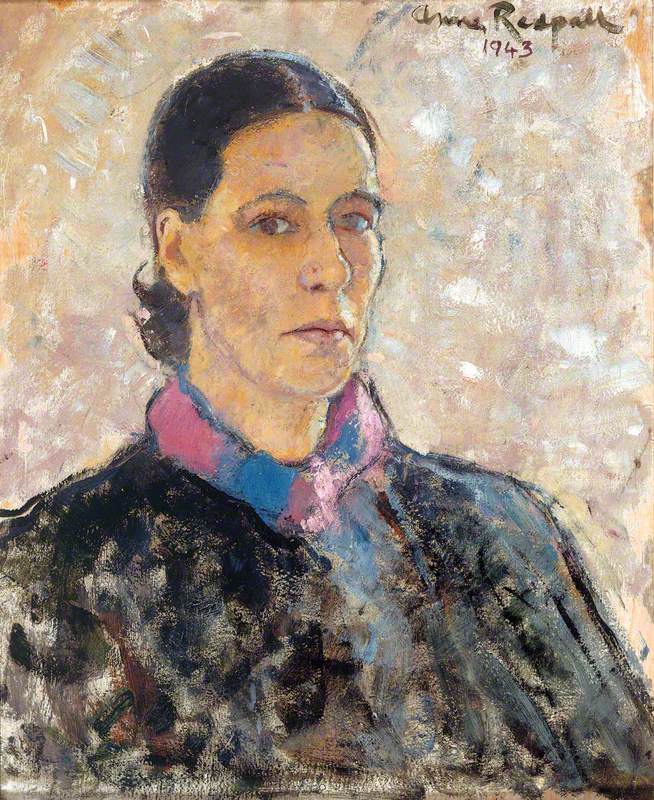

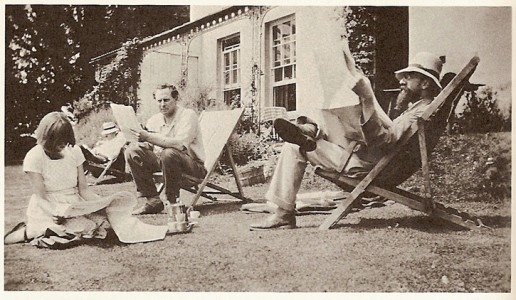

Walker sometimes made her difference apparent in her dress: photographs and written accounts capture her 'mannish' shirts and ties, plain tailored clothes and severe cropped fringe.

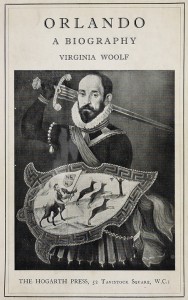

She painted herself in shirt and tie in around 1925, and her painting of a short-haired young woman in similar dress titled Portrait of an Elizabethan Youth is surely a reference to Virginia Woolf's Orlando (1928), which features a character who changes sex over the course of the novel.

But Walker could also make an appearance as the epitome of chic femininity, as in her self-portrait of around 1930 with canvas and brush in a black frock with dazzling jewellery, which was shown in Venice two years later.

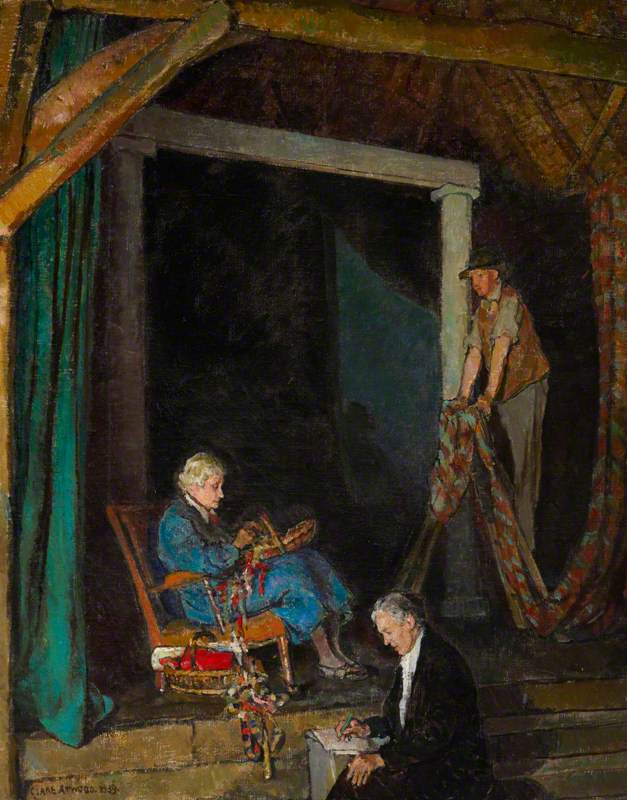

Walker was a late starter as an artist. She was 38 when she enrolled at Putney School of Art, and then went on to the Westminster School of Art where Frederick Brown (1851–1941), who later became Slade professor, was teaching. She followed Brown to the Slade, also studying under Walter Sickert there, and was to return three times for further training. But it was her relationship with a fellow woman artist who died young, Clara Christian (1868–1906), which was to have the greatest effect on her life and work.

Walker met Christian when she was aged 19. Christian owned two houses in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, one of which she transformed into studios, and Walker settled there, the two women living and working together. They were immortalised in the critic George Moore's lightly fictionalised three-volume memoirs Hail and Farewell (1911–1914) as 'Stella' (Christian), and 'Florence' (Walker). They had met Moore in Paris while travelling to see the great works in European collections, and the three became friends.

While Christian's sexuality appears to have been fluid – she was to have an affair with Moore, and died in childbirth following her marriage to the architect Charles McCarthy – Walker's admiring and even desiring eye focused on her own sex is captured in Moore's writing. 'Florence' declares that 'no more perfect mould of body than Stella's existed in the flesh – perhaps in some antique statues of the prime, though even that was not certain.'

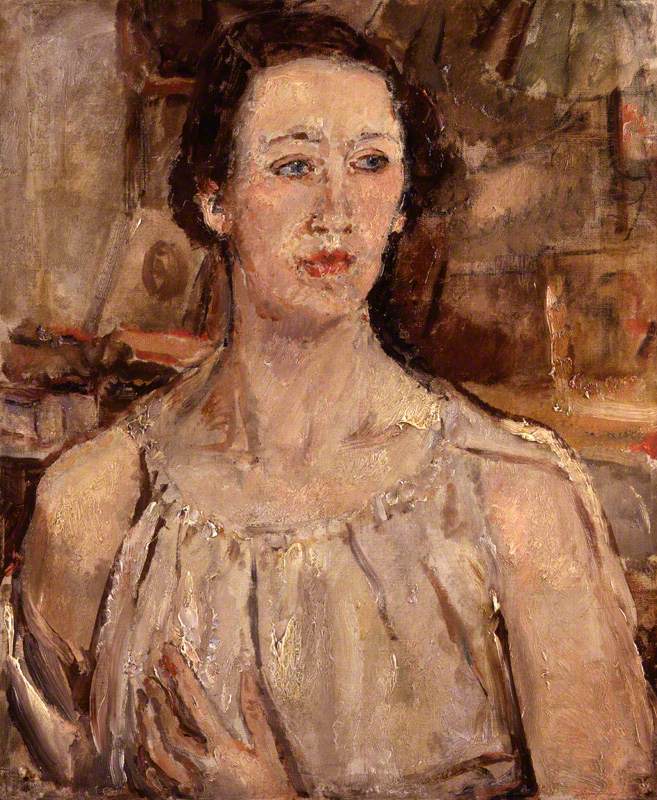

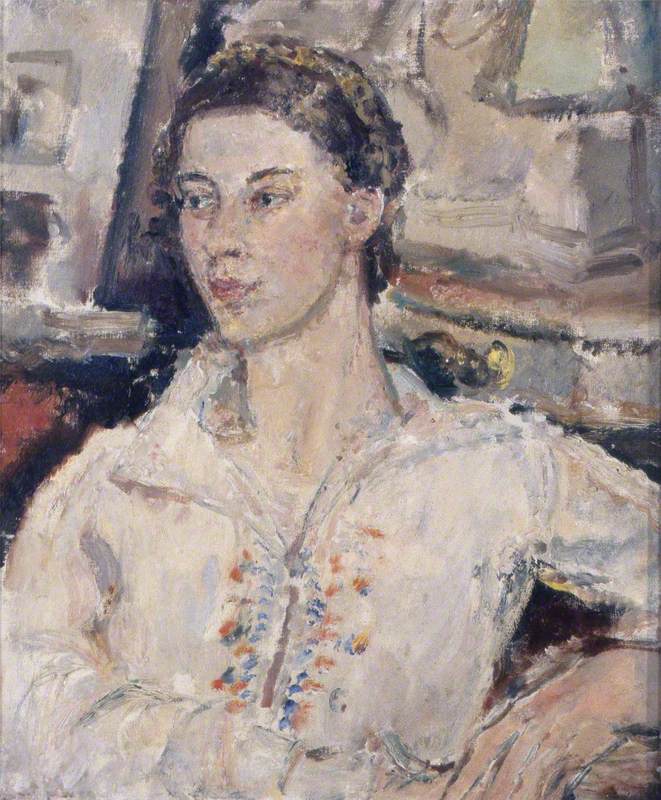

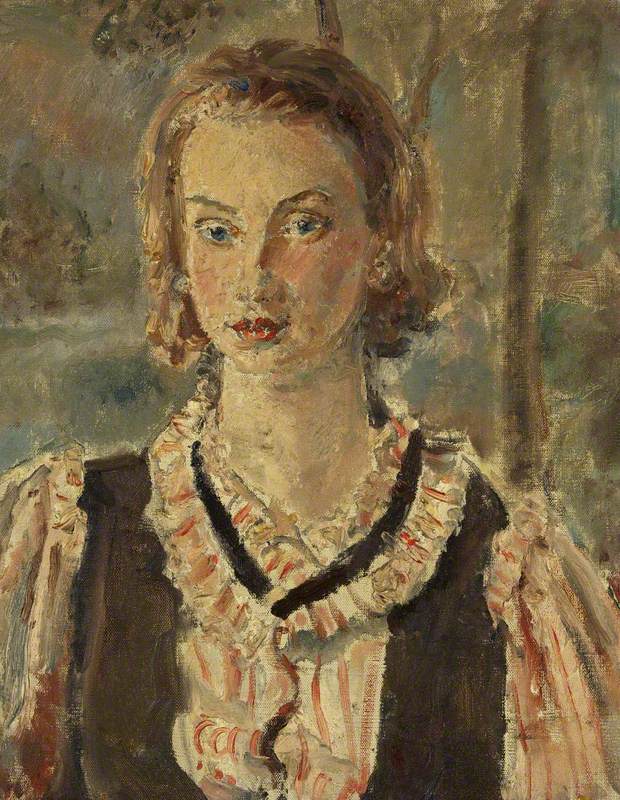

Throughout her life, Walker painted women more than any other subject.

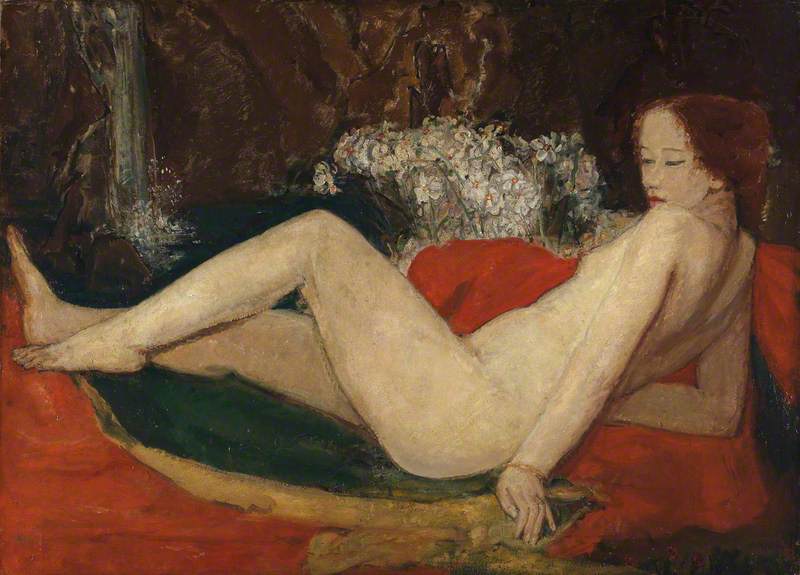

A 1916 nude with the kind of symbolist seductive darkness of a Paul Gauguin was given the enigmatic title Silence of the Ravine.

She painted portraits of fellow women artists including a young Barbara Hepworth and of Vanessa Bell.

This portrait of Barbara Hepworth was painted when she was a teenager by noted artist Ethel Walker, who lived part-time in Robin Hood’s Bay. See Walker's portrait and many of Hepworth's works at The Hepworth Wakefield. https://t.co/ue1UGeahmA Photo: George Baggaley pic.twitter.com/dMZEp8Tti2

— The Hepworth Wakefield (@HepworthGallery) February 1, 2020

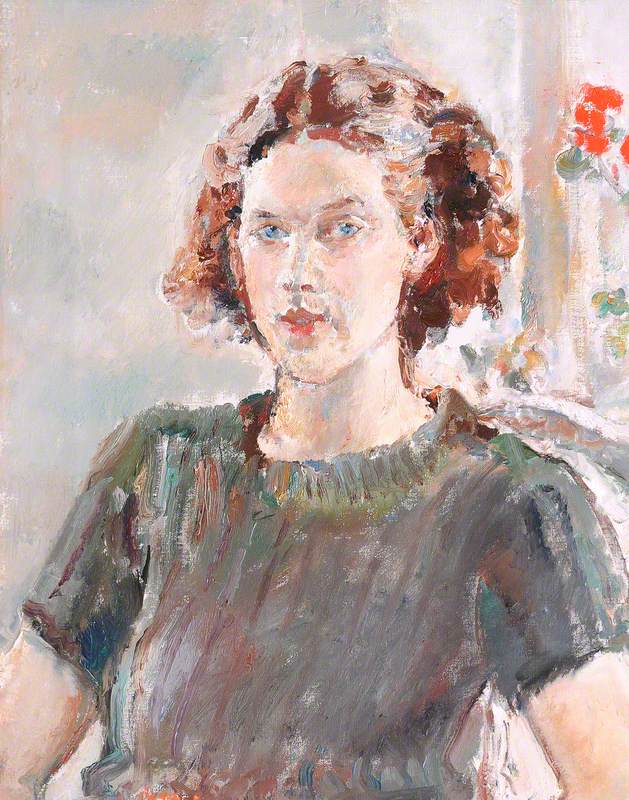

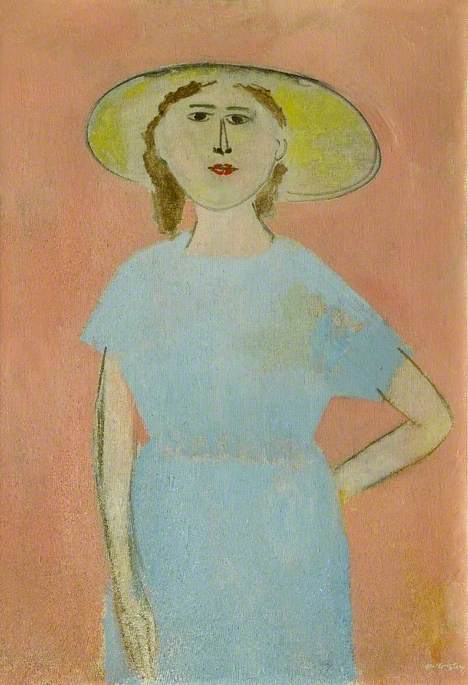

Another example is the anonymous but strikingly individual and self-possessed The Young Sculptress.

She also painted women in more conventional feminine roles. She had made her name first as a British Impressionist (she and Christian had discovered the group's work in Paris with George Moore).

An early painting of a mother and children in a garden is a beautiful example of her skill with light and in painting en plein air.

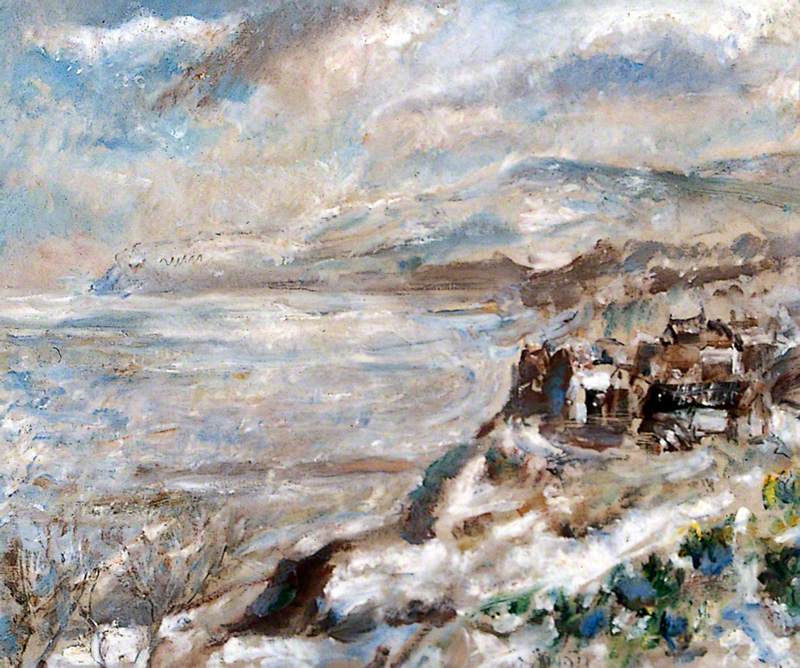

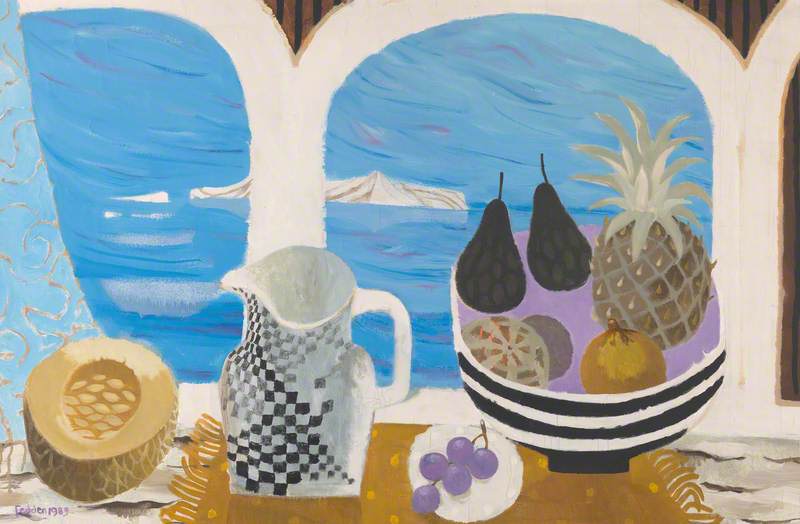

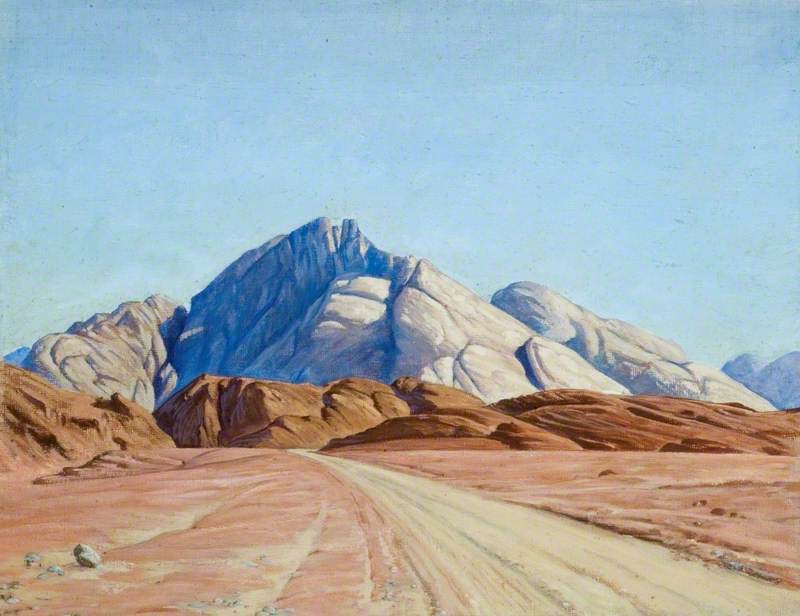

She continued this type of practice in seascapes at Robin Hood's Bay, Yorkshire, where she had a studio.

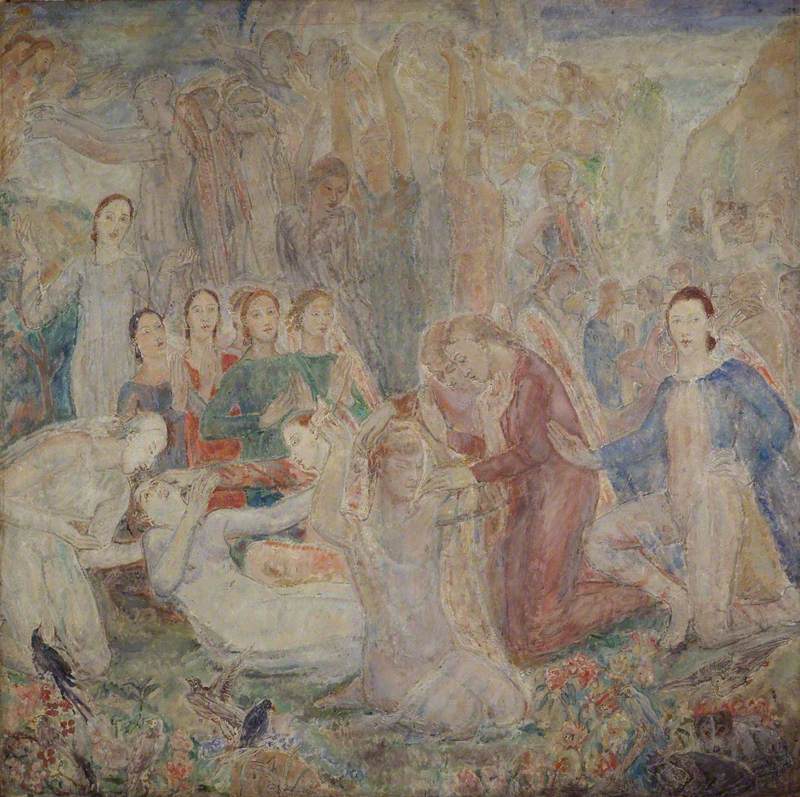

Walker's growing interest in philosophy, mysticism and religion, from the work of Emanuel Swedenborg to eastern faiths, united with her new interest in making large-scale work, led to her most ambitious paintings. She had long been an admirer of the work of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, the French artist and muralist whose work inspired many later modernists, including Gwen John. Walker returned to the Slade for specialist training in fresco and tempera painting in 1912 and 1916.

Her allegorical 1914–1915 painting The Zone of Hate, which is nearly two and a half metres square, was made in response to the development in her practice and the descent into war.

Walker began work on it the week hostilities erupted, not believing that the conflict would be over by Christmas and the Kaiser defeated (as the jingoists were proclaiming), rather that the war would last for years and that evil was taking over the world.

Fifteen years later she painted a companion piece, The Zone of Love, in which the awakening of a soul is depicted as the awakening of a young girl.

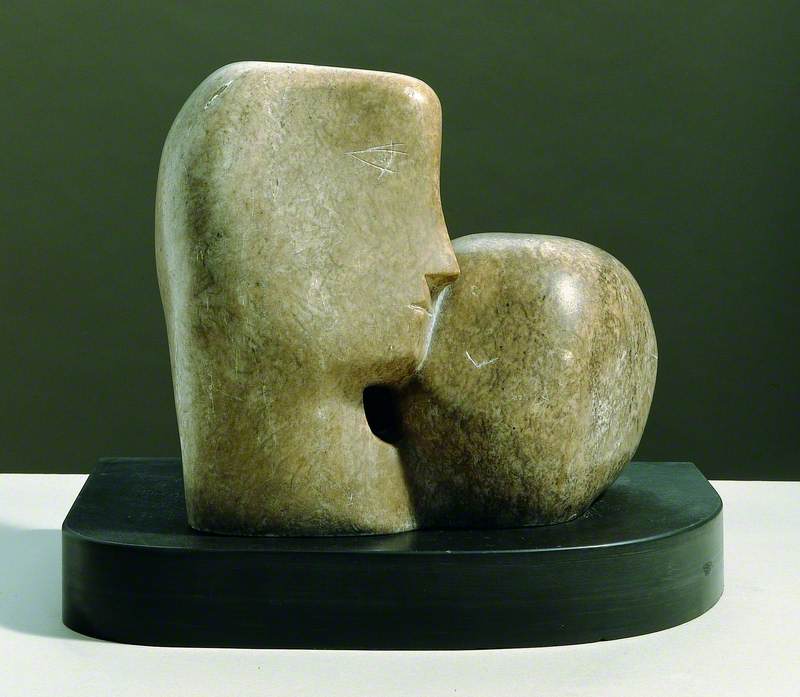

A marble bas relief of the same subject is in the Royal Academy.

Her 1920 painting The Excursion of Nausicaa reimagines Homer's Odyssey but relegating Odysseus himself to the background. Walker's eye focused instead on a group of women, painted with a pared-back palette of exquisite flesh tones, with flashes of cool blue, red and green.

On the occasion of her 1939 exhibition at The Lefevre Galleries, Walker wrote to her friend Grace English (who was to write a biography of Walker which was never published) a letter which reveals her frustration as an artist who was not (and still has not been) given her due:

'Thank you for your beautiful letter about my show, which filled my soul with completest happiness and contentment & made me able to dispense so easily with the limited survey of all the obtuse press opinions... Because I am a woman I have to be patronised it seems with a sea of futilities and adjectives.'

Alicia Foster, curator