Edgar Herbert Thomas was born in humble circumstances on a farm near Llanddewi Velfrey, Pembrokeshire, in 1862. Half a century later, in 1913, he would show 137 of his paintings at the Doré Galleries in London. At that time (and probably since), this was the largest one-person exhibition of the work of any living Welsh painter ever held outside Wales. But in 1936 Thomas would die in obscurity, and his most ambitious and celebrated pictures would be destroyed, apparently by the relatives who had inherited them.

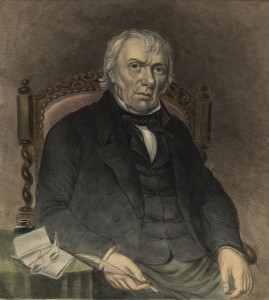

Image credit: Pembrokeshire County Council's Museums Service

Edgar Herbert Thomas (1862–1936)

Pembrokeshire County Council's Museums ServiceThe rise of Thomas might well be seen as the fulfilment of the artistic aspirations of a generation of ambitious Welsh intellectuals and patrons in the period of Cymru Fydd – 'Young Wales' – the movement of national revival that flourished from the last quarter of the nineteenth century until the First World War. Equally, his subsequent disappearance from the Welsh art world and, indeed, from the national memory, reflects also the fate of that movement of high aspiration for Wales, after the war.

As an adolescent, Thomas was apprenticed as a weaver, working at two mills in Pembrokeshire. After serving his time, he worked at the flannel mill of Mr Wilson at Pontypridd, where he also attended art classes taught by the painter William Morgan Williams (Ap Caledfryn). Through his connections, Ap Caledfryn obtained a post for the young man in the art department of the Western Mail newspaper.

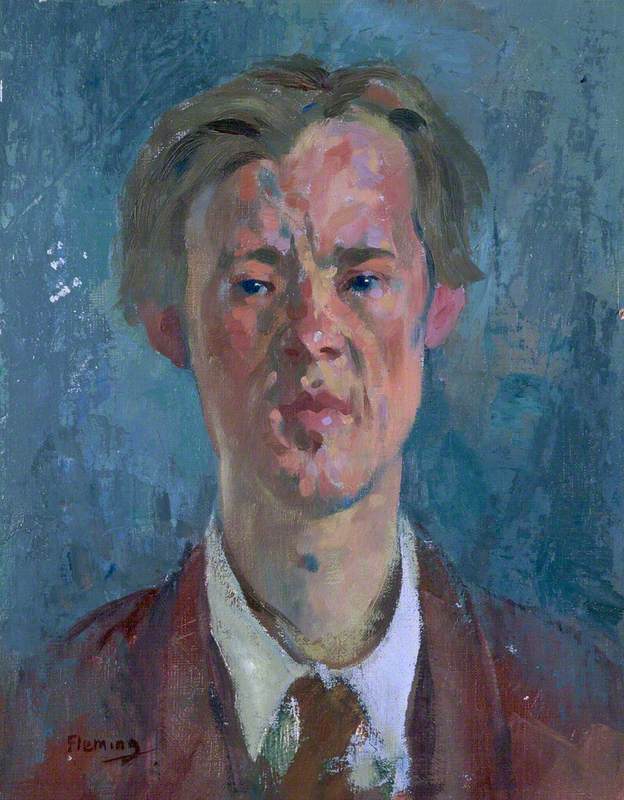

Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

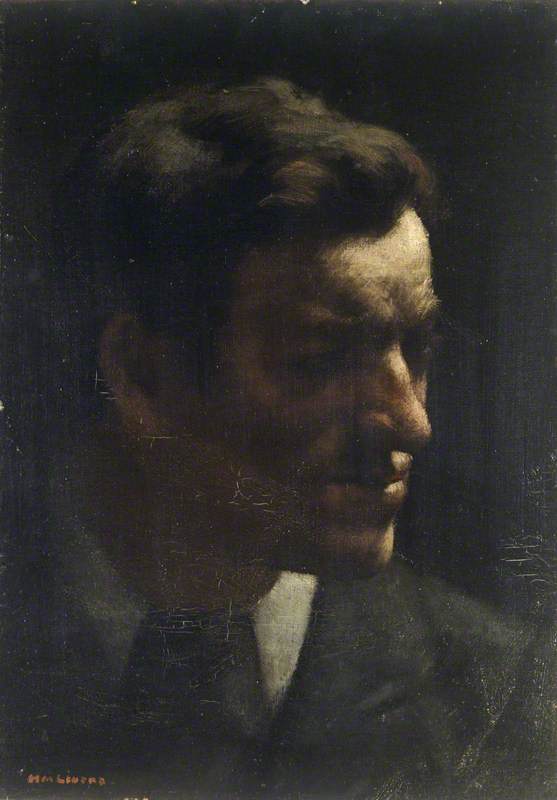

Edgar Thomas (1862–1936) early 20th C

Horace Mann Livens (1862–1936)

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesIn 1883 the National Eisteddfod was held in Cardiff, an event that included art competitions on an unusually large scale, driven by the interest of a group of influential intellectuals who associated together in the Cardiff Naturalists' Society. Edgar Thomas was among the competitors and was awarded a silver medal for a drawing. The adjudicators, the Dutch-born painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the London art critic Frederick Wedmore, praised his work in the Western Mail.

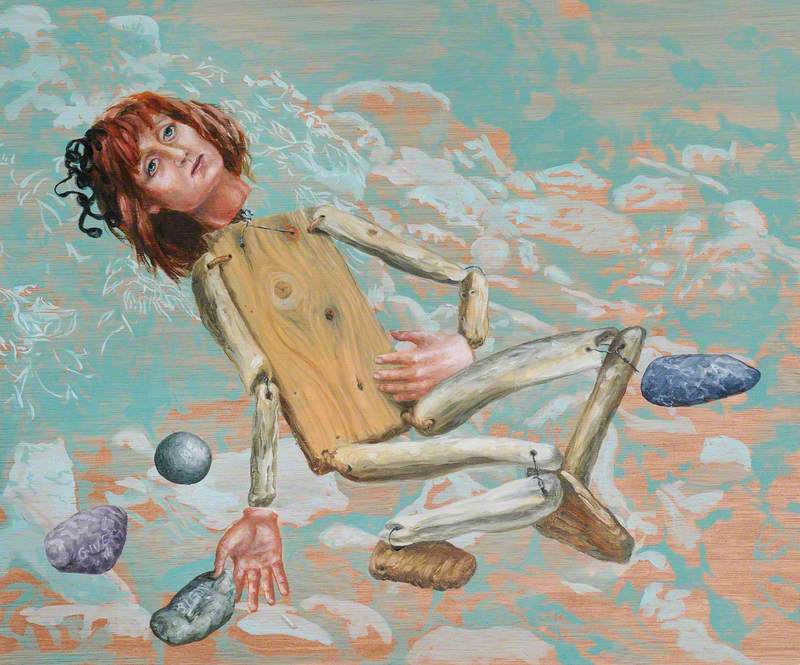

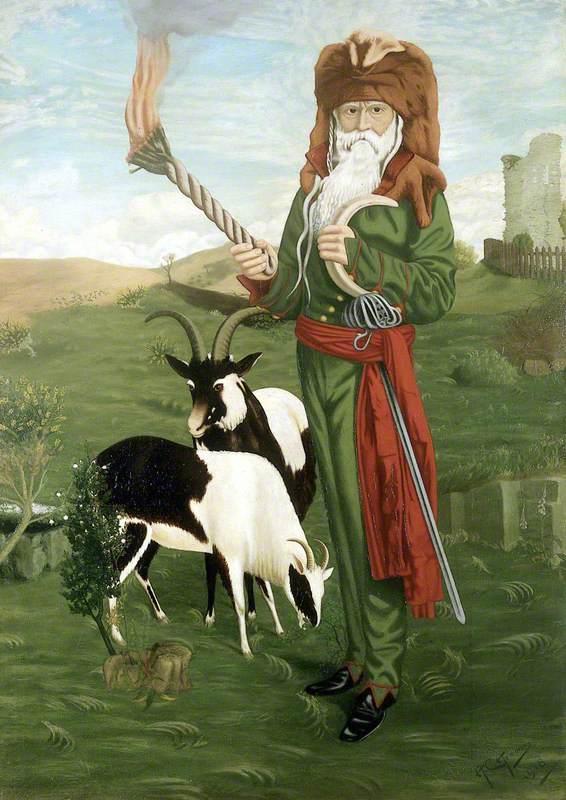

Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

The Swell of Hope early 20th C

Edgar Herbert Thomas (1862–1936)

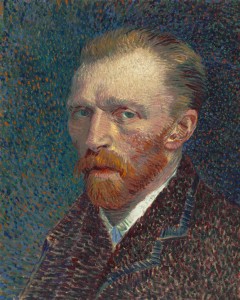

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesDespite an undignified public spat between rival claimants for the credit of encouraging the young Thomas, the Marquess of Bute financed his further training, briefly in London but most importantly at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Antwerp, where Alma-Tadema himself had studied. Thomas was a contemporary there of Vincent van Gogh, for nine months.

After this brief exposure to the swirling aesthetic fashions of the Belle Époque, including – significantly – Symbolism, Thomas returned to Wales, and eventually settled as a lodger at a house in Blackweir, on the northern edge of the town. He would remain there for the rest of his life.

Portrait commissions followed, mainly from members of the Cardiff Naturalists' Society, and all seemed well until the spring of 1892, when Thomas began to display signs of mental illness. Found 'wandering at large', he was taken to the workhouse and from there was committed to Bridgend Lunatic Asylum. His behaviour over his three months in the asylum was meticulously recorded:

'He is not making any progress. Will not wear a hat or scarf because God gave him hair to cover his head & a scarf is unhealthy. Full of philanthropic projects, "want to see my fellow man have his rights". He is anxious to make everyone a Welshman... In conversation he gets excited & then indicates that he derived his knowledge direct from the Deity. He believes he can foretell events from the appearance of the moon.'

Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Edgar Herbert Thomas (1862–1936)

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

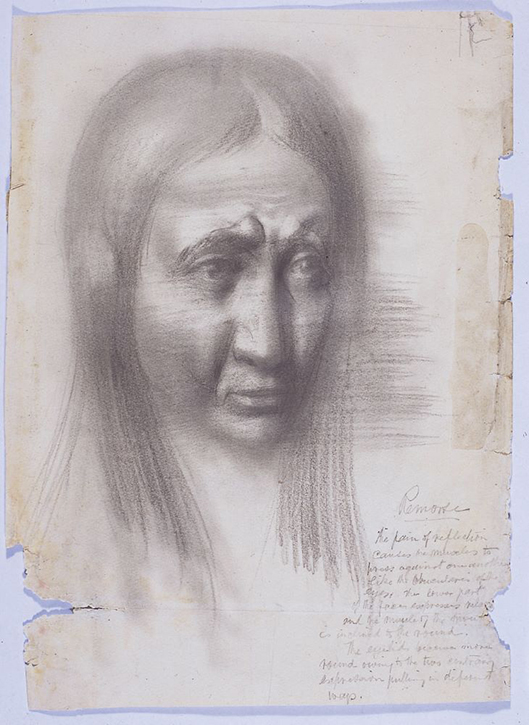

Image credit: private collection

Remorse

c.1899, pencil on paper by Edgar Herbert Thomas (1862–1936), private collection

Thomas was released against medical advice from the asylum on the initiative of a relative who 'thinks patient quite sane; accepts his ideas as Gospel; and believes patient has been misunderstood by all.' Locating the dividing line between delusional and visionary appears to have been the issue. Thomas's subsequent overtly symbolist paintings, and indeed his landscapes, portraits and still-life subjects, all manifested the mystical state of mind of the visionary, disposed to search for meanings beneath the objective reality of the natural world around him.

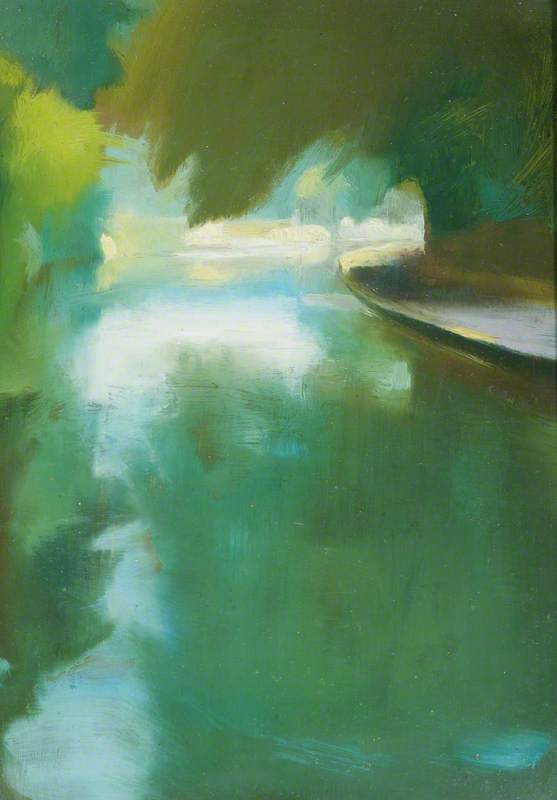

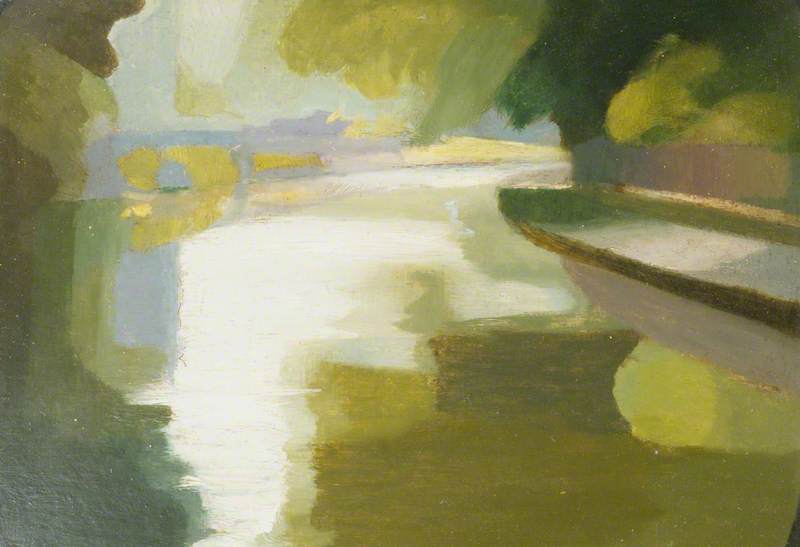

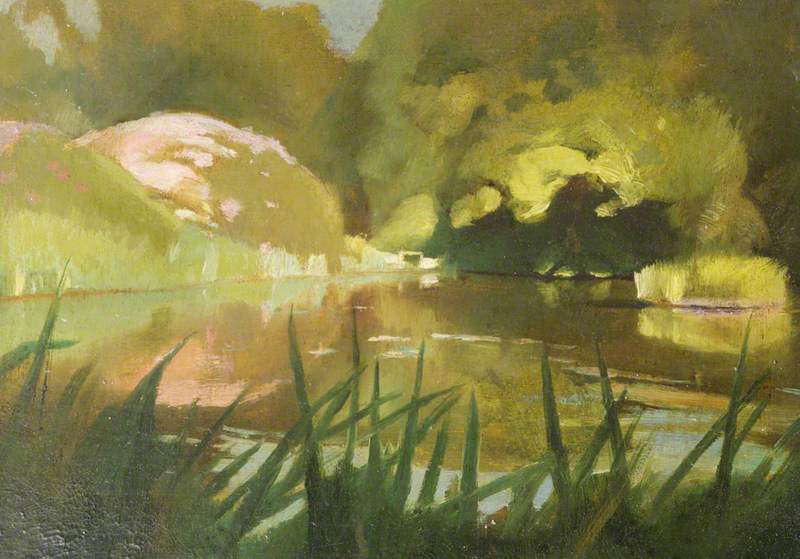

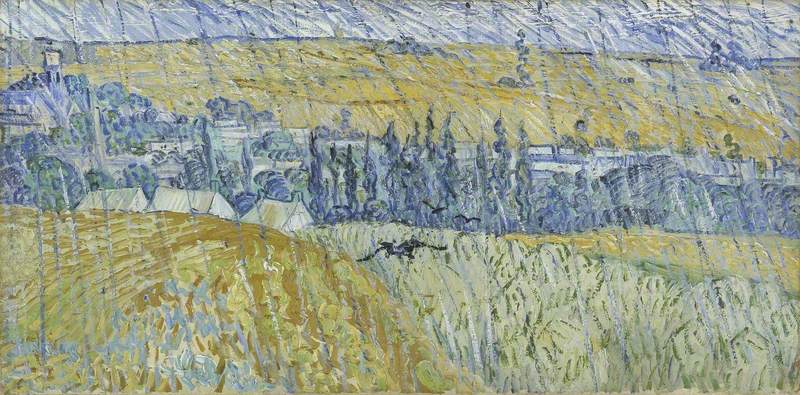

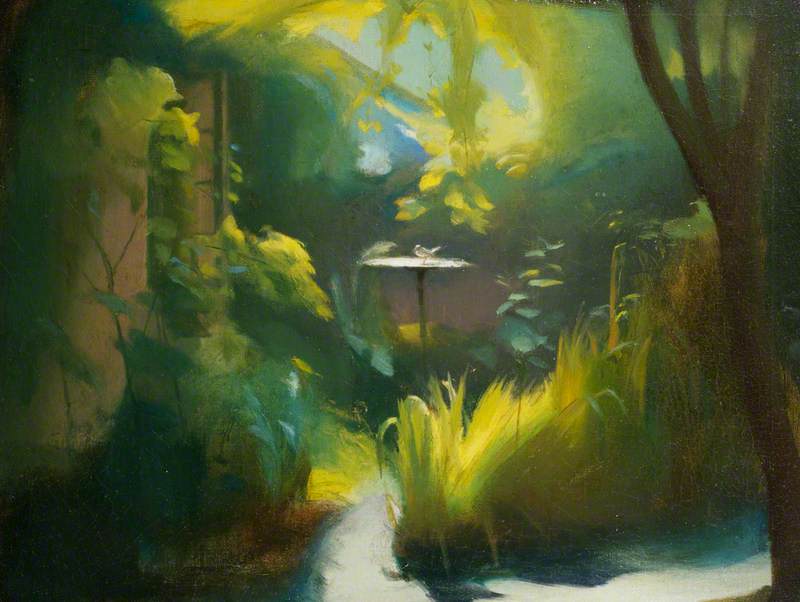

Thomas's lodgings at Blackweir backed onto the Glamorgan Canal, and in 1893 he began to paint a series of at least 80 studies of the same view from his garden, around a turn in the waterway. Initially, the work was dark in tone, reflecting the painter's palette before his psychosis, but gradually it lightened.

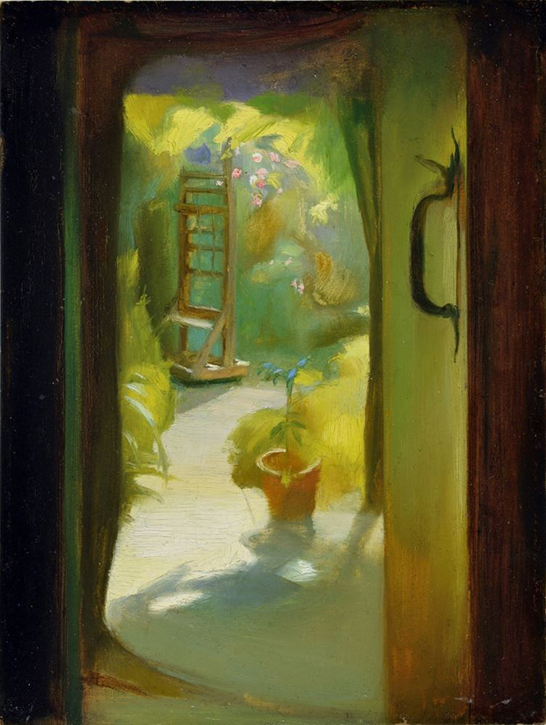

Image credit: private collection

A Bright Summer's Evening

1917, oil on canvas by Edgar Herbert Thomas (1862–1936), private collection

In 1917 he painted a view from inside the rear of his home towards his empty easel, standing in the garden above the canal. The full tonal range, from the dark of the interior to the light of A Summer's Evening (the title he gave to the work), strongly suggests a deeper symbolism, expressive of a personal inner darkness contemplating the brilliant light beyond. Later in his career, moving away from the garden of his home to paint in the company of his protégé, Henry Walter Shellard, his palette would be dominated by an intense range of greens.

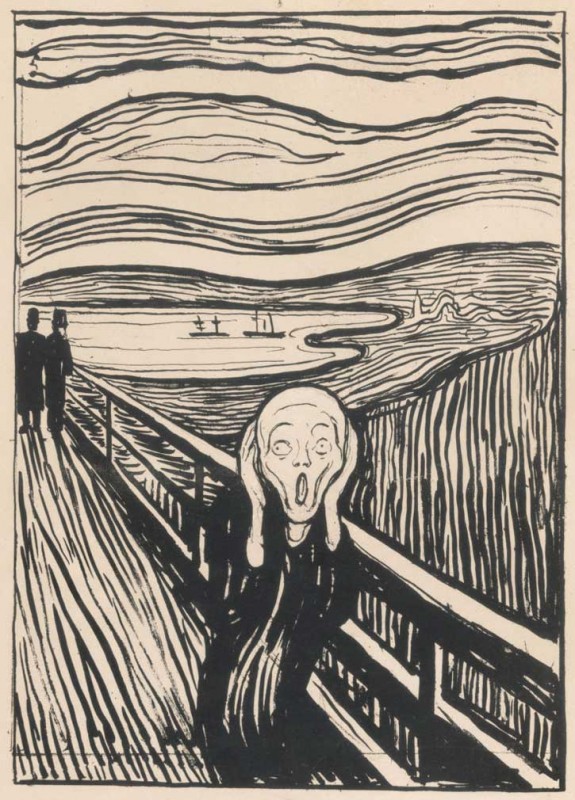

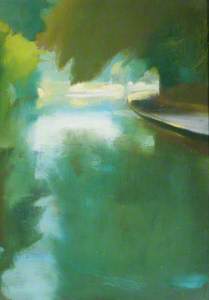

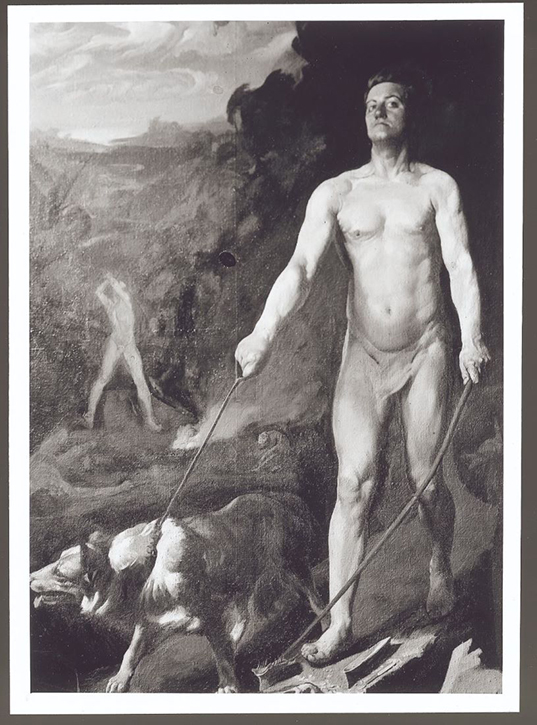

Image credit: private collection

Intellectual Blindness Following Old Thoughts

1897, photograph of a lost oil on canvas painting by Edgar Herbert Thomas (1862–1936)

Thomas's fascination with light in the natural world and with its deeper meaning had been expressed in his most celebrated symbolist work, The Birth of Light, exhibited at the Cardiff National Eisteddfod of 1899. The Western Mail regarded it as 'a great and wonderful production, evidently emanating from the weird and mystical imagination of the Celt.'

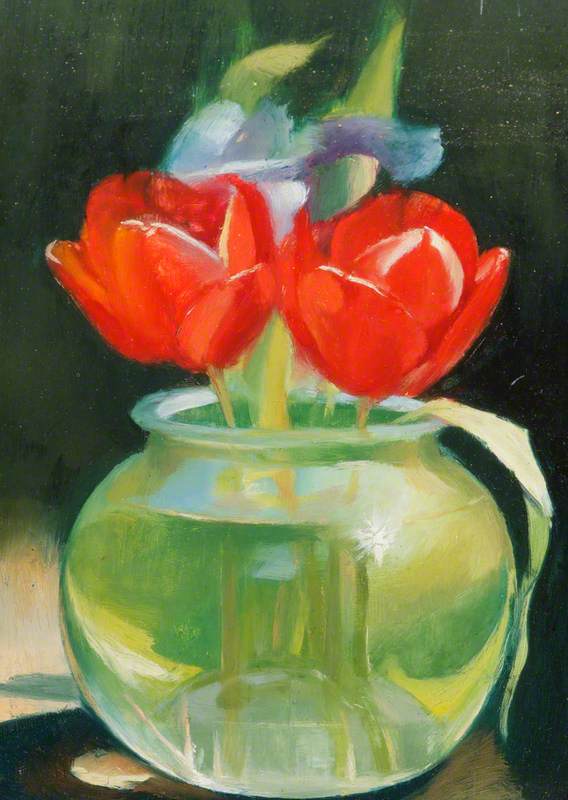

Along with Intellectual Blindness Following Old Thoughts, a large-scale picture painted two years earlier, it was undoubtedly informed to a degree by the work of George Frederick Watts, often claimed by Welsh intellectuals of the period as a fellow Celt. However, it was in Thomas's small-scale works, and especially the many luminous pictures of flowers, usually set in strongly coloured or translucent containers, that Thomas achieved a unique expression of his complex vision, paradoxically expressed in the simplest of formal terms.

Image credit: Pembrokeshire County Council's Museums Service

Red Berries and Flowers in a Gold Vase

Edgar Herbert Thomas (1862–1936)

Pembrokeshire County Council's Museums ServiceThe series of flower pictures and landscapes continued after the First World War, but critical attention was directed elsewhere, towards Modernism. At home, the focus turned towards Augustus John, in particular, who supplanted Thomas in the art world and in the public mind as the most important Welsh painter.

From the high point of his London exhibition and the deployment of the word 'genius' by his supporters in Cardiff, the work of Edgar Herbert Thomas was ignored, and much of it lost. But some pictures are held in private collections and by National Museum Wales, and fortunately a substantial body of his remarkable small works has found its way into the collections of Scolton Manor in Pembrokeshire.

Peter Lord, art historian and writer

Peter Lord includes a chapter on Edgar Herbert Thomas in his 2020 book Looking Out: Welsh Painting, Social Class and International Context, published by Parthian

Image credit: Parthian Books

Looking Out: Welsh Painting, Social Class and International Context

Peter Lord (2020)

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding