The humanity of bodies

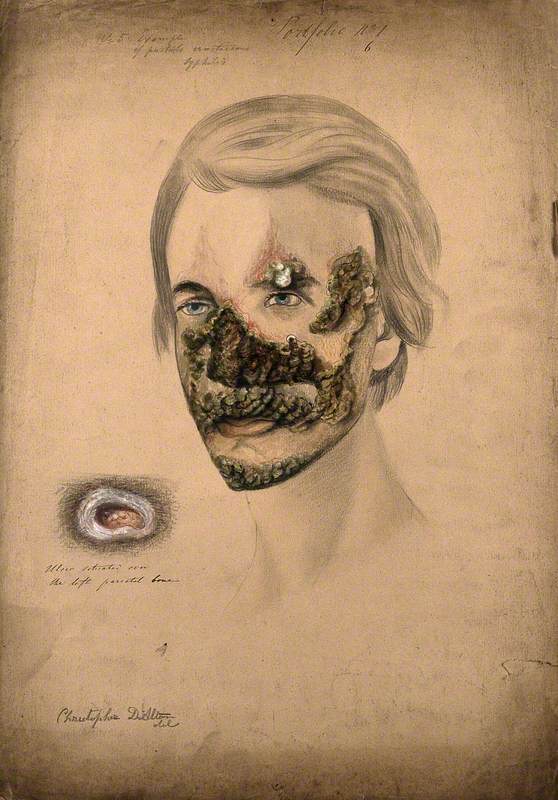

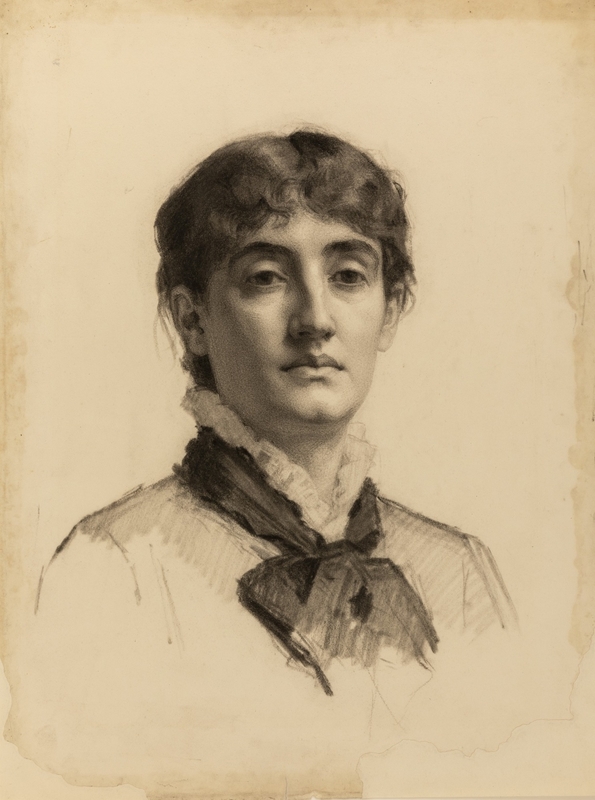

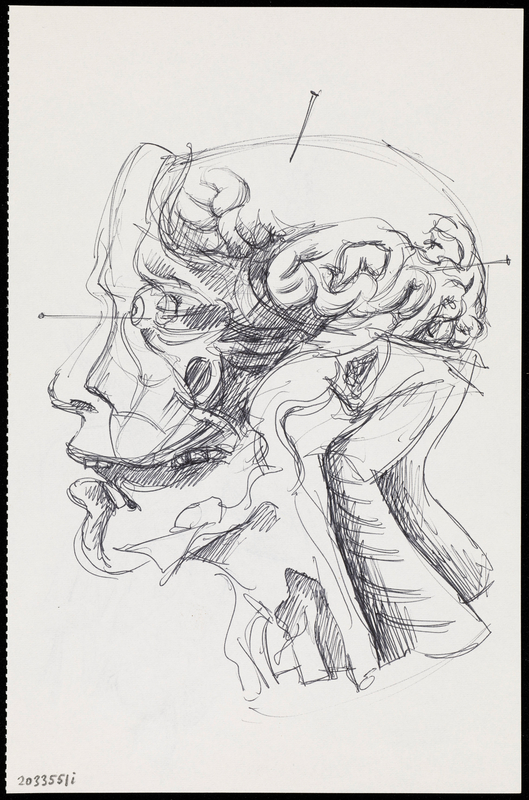

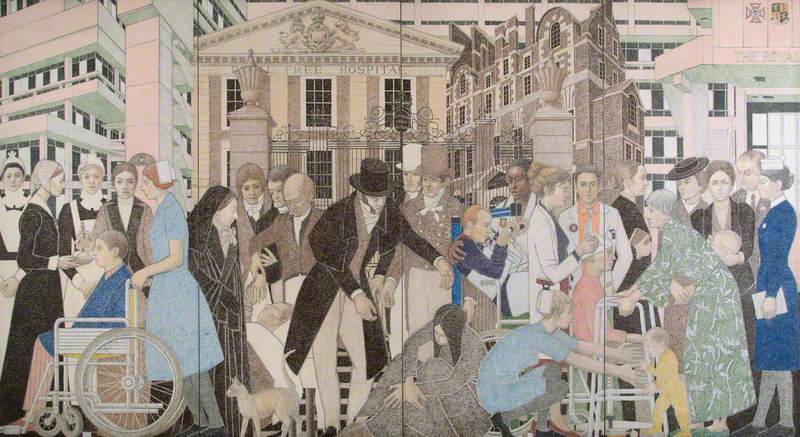

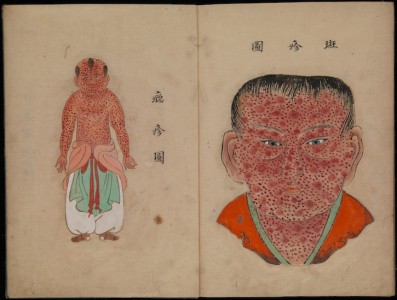

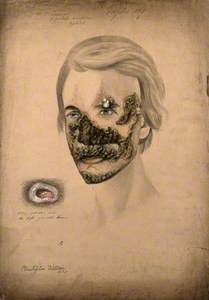

Look at this man – this unnamed, suffering man who sought treatment at the Royal Free Hospital in London sometime in the mid-nineteenth century, and sat for Christopher d'Alton, the hospital artist.

D'Alton's work at the Royal Free was, in one sense, entirely practical: he was employed to depict patients with unusual conditions. So this is a case record of sorts, intended to capture and communicate clinical information. But it is a great deal more besides.

Like so many medical illustrations, d'Alton's watercolours are striking because they are also portraits. They convey character, bearing, all the quirks of individuality, but also the burdens of pain and disfigurement. His subject here is fine-boned and long-faced, with weary eyes and tousled, faintly Romantic locks. You might cast him as Hamlet, were it not for a terrible, fulminating affliction of his skin. D'Alton's achievement is subtle and humane, an equipoise of empathy and distance. It reminds us that artists and anatomists share a common concern with the body, its form and movement, the expression of truth through flesh, and the question of how to represent it convincingly. Both have cut bodies to pieces, boiled their bones, preserved them in spirits or modelled them in wax, to learn their secrets.

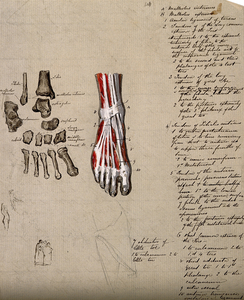

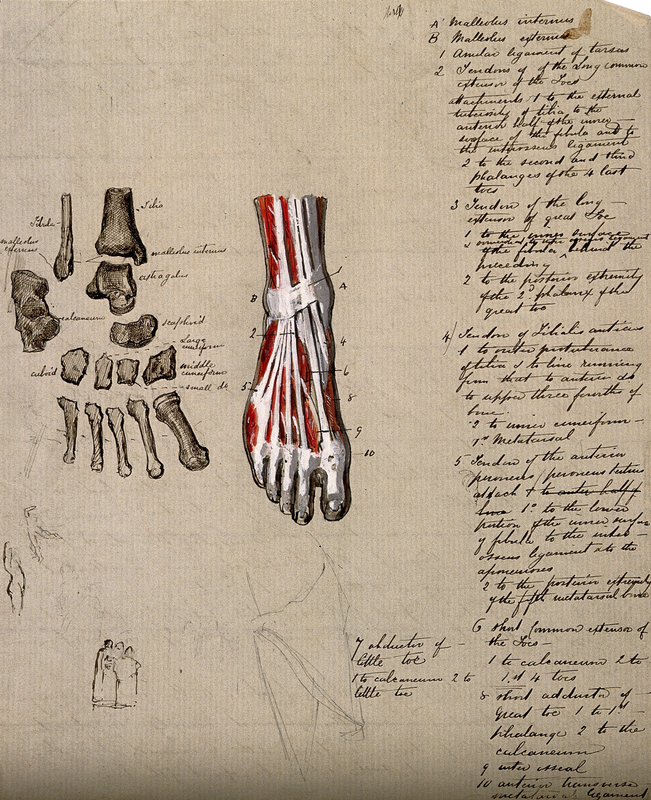

Bones and Muscles of the Foot: Two Figures, with Thumbnail Sketches of Figures in Action

19th C

unknown artist

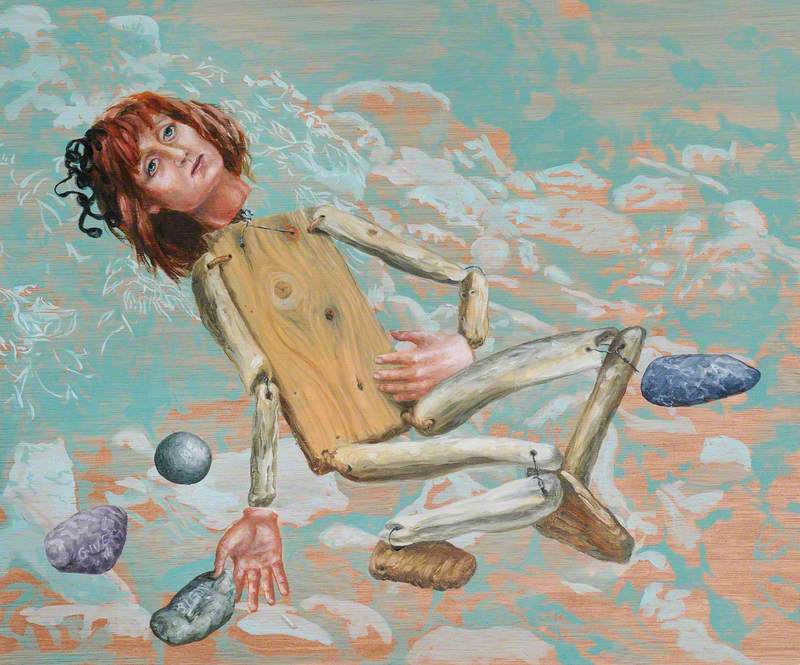

This nineteenth-century sketch catches the process in action. Made on cheap brown paper, this is no carefully finished masterpiece but a working draft – and we have no idea whether its maker was studying art or anatomy. The textbook colours and the careful list of Latin names in spidery copperplate suggest an eye for clinical detail. But look at the painterly crosshatching of the bones and the stylish little groups of figures. Is this a medical student doodling in the margin, or an artist working out a composition on the fly?

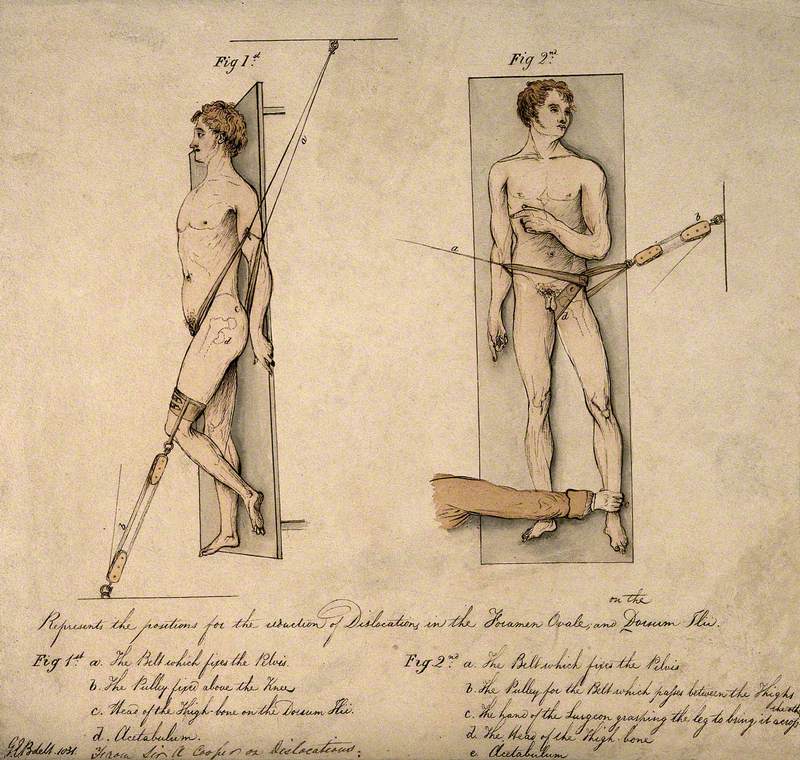

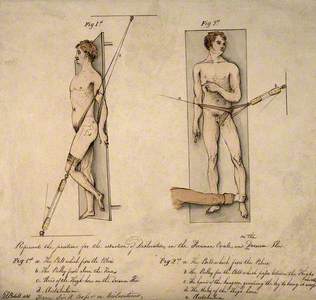

Comprehending the body is one thing – treating it may be quite another. Much of medicine, especially surgery, has depended on tacit knowledge – skills that may be comparatively easy to demonstrate but maddeningly difficult to capture. In this 1831 drawing, the military surgeon George Eleazar Blenkins shows us how to reduce a dislocated hip. Set against nautical pulleys and ropes, the vulnerable form of the patient seems touching, even a little comic. He – and we – must trust the expertise embodied in Blenkins' sleeved arm, reaching in to pop his hip back into its socket.

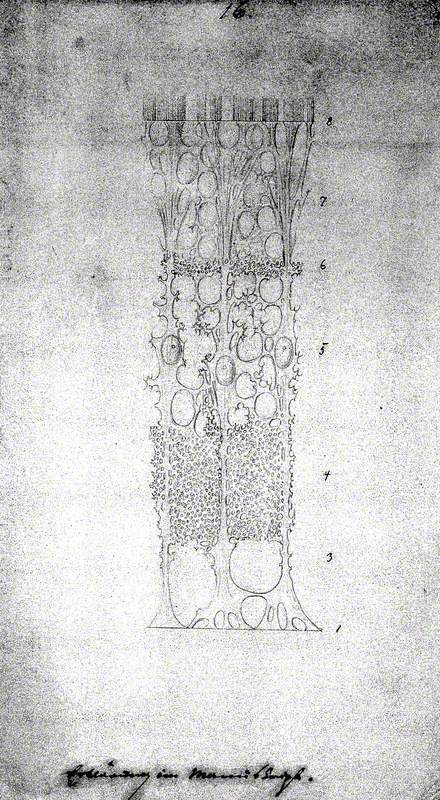

Connective Tissue of the Retina: Microscopic View

1870 (?)

Max Schultze (1825–1874)

Blenkins' heroic intervention is built on gross anatomy, the details you might observe in a dissecting room. Later clinicians and scientists, though, were fascinated by the new worlds revealed through microscopes. In this delicate, almost abstract sketch the German microscopic anatomist Max Schultze answers a question familiar to astronomers, psychonauts and mystics: how to depict something only you can see? New disciplines like cell pathology depended on rigorous collective empiricism and a searching demand for honesty. Were these strange structures real or merely an optical illusion, even a figment of one observer's imagination?

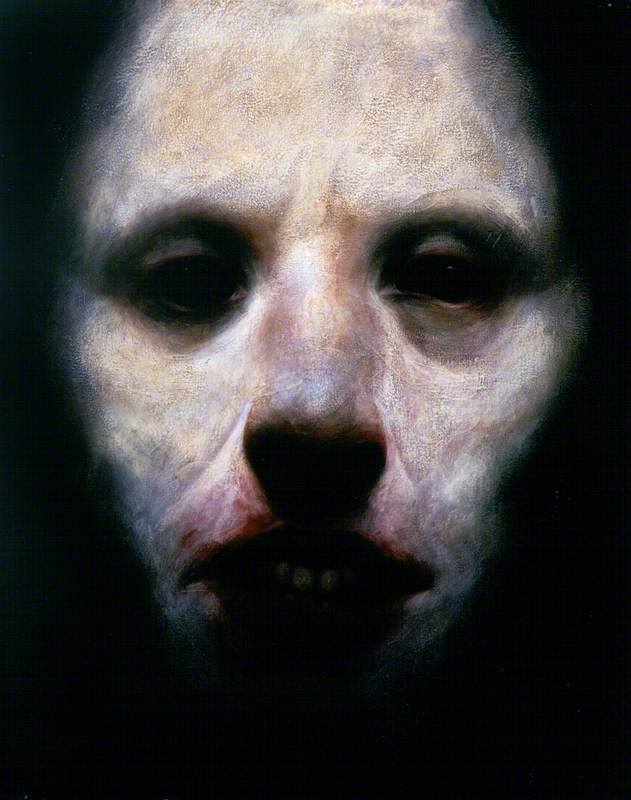

Whatever they might represent, illustrations like these are far more than photorealistic presentations of what an anatomist saw on a slab or a clinician encountered on a ward. Beneath a carefully crafted surface of clinical objectivity lie many layers of meaning, and the traces of our endlessly difficult relationship with suffering, disease and death. These images are portraits of their age, of its hopes and anxieties, of what it thought it knew and what it knew it did not.

Classification and control

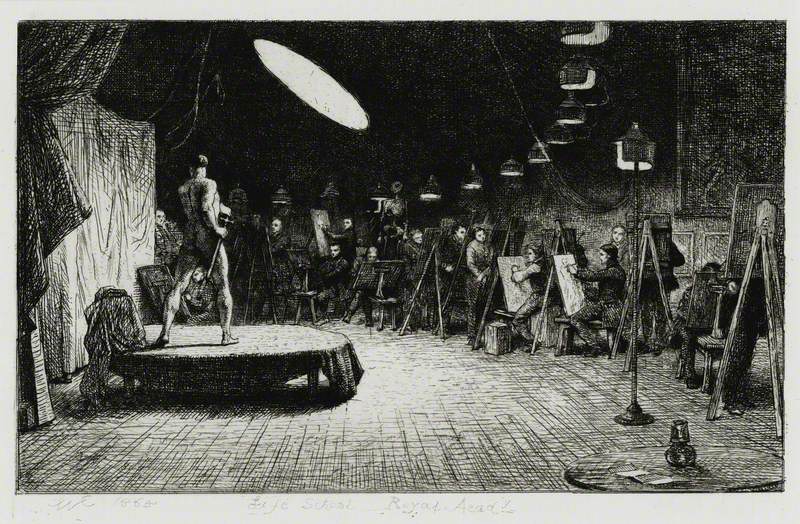

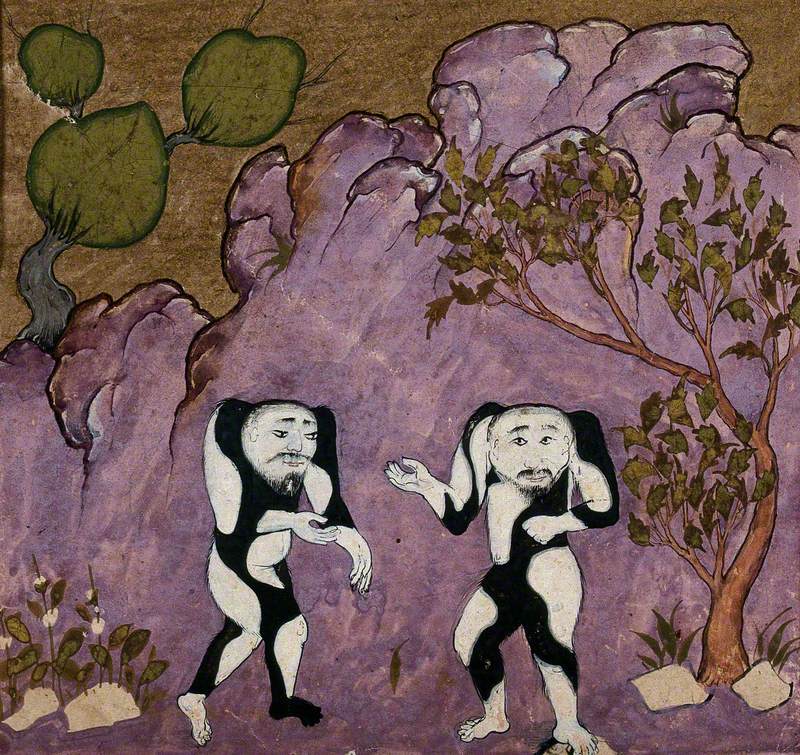

Artists have painted dissections for centuries – just think of Rembrandt's anatomy lessons. But this is a surpassingly odd scene, and the harder you look at it, the weirder it gets. Two men lean over the almost-naked corpse of a woman, her hair in a braid and her toes pointed like a ballerina. (Anyone who has been inside a dissecting room will tell you that the dead never look so radiantly alive.) One peels back the skin of her chest as if it were a cardigan. Lamplight catches the august forehead of Johann Christian Gustav Lucae, a Frankfurt anatomist who devoted his career to the 'racial morphology' of the skull. According to the artist Johann Heinrich Hasselhorst, who made this chalk study for an oil painting, they are dissecting her 'in order to determine the ideal female proportions.' No sniggering at the back, gentlemen; this is science.

We might not think of looking for the secrets of beauty in the dead, but deeper strands of culture run through this very nineteenth-century picture. There's the Christian claim that humanity was made in the image of God, and hence understanding the body might reveal something of divine purpose. There's a metaphor beloved of early modern natural philosophers: nature personified as a beautiful, flighty woman, who must be pursued, captured and stripped to reveal her secrets. Beneath all this, though, is an impulse that became the central project of the European Enlightenment: classify the world and, with this knowledge, control it.

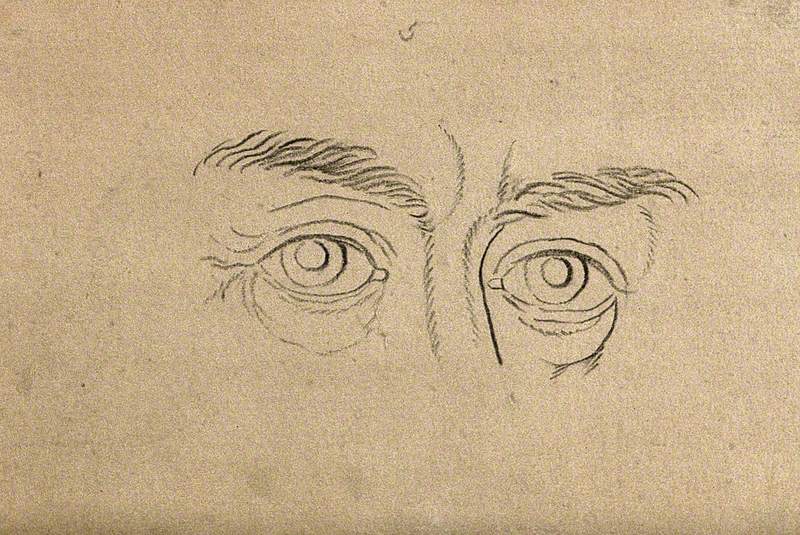

The objects of this avowedly rational gaze might be the bodies of young women, or the native peoples encountered on voyages to the Pacific, or the faces of our friends. For the Swiss theologian Johann Kaspar Lavater, the curve of your eyelid might reveal your innermost strengths and flaws. Thomas Holloway's engraving – eyes which show 'a good but weak and thus possibly suspicious character' – comes from his five-volume English edition of Lavater's Physiognomische Fragmente (1775–1778).

Classification is a project with – to put it mildly – a double face. Infectious diseases have always travelled with trading ships and conquering armies, and physicians first acquired a measure of state power through their involvement in public health. Today, the authority of modern scientific medicine rests, in large part, on its ability to classify and control disease. Many of us might be personally grateful for a discipline that can swiftly identify a new pathogen, devise effective vaccines and recommend ways to limit its spread.

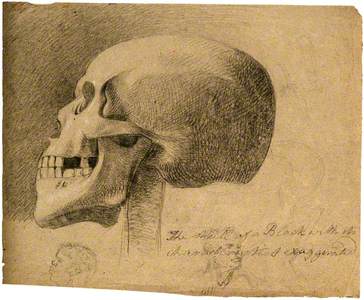

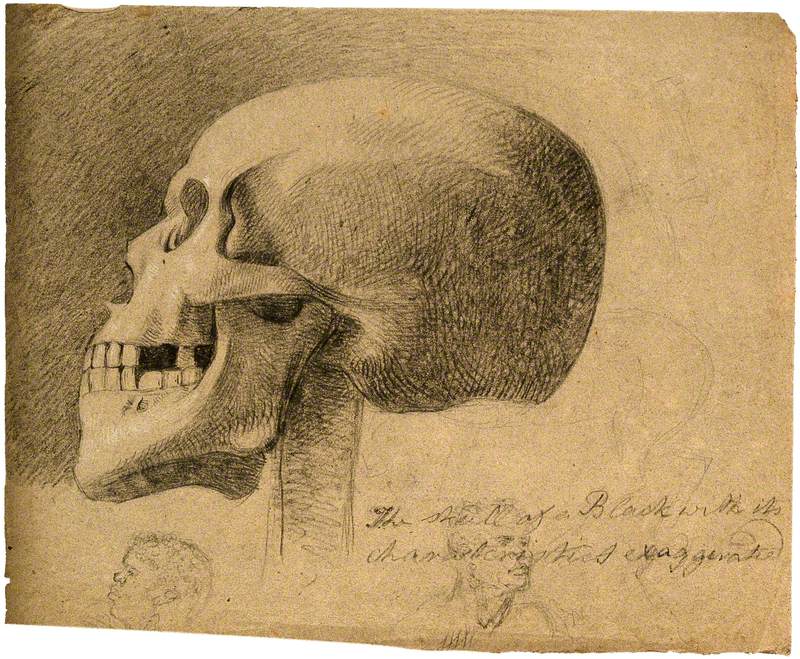

The Skull of a Black Man, with Two Smaller Sketches of Heads of Black People

c.1815

Charles Landseer (1799–1879) (possibly)

But the coronavirus pandemic also reminded us that medicine's encounters with politics can be extraordinarily complex and contentious. And a generation of historical scholarship has highlighted how classifications of medical knowledge so often reflected, even reinforced, rigid cultural or moral hierarchies of human difference – whether in gender, ethnicity, class, disability or more besides. These hierarchies have been all the more insidious for acting, as it were, beneath our gaze, giving us the impression that we merely observe how things are. As we contemplate Charles Landseer's c.1815 drawing of 'the skull of a Black [sic] with its characteristics exaggerated', we may wonder what prejudices and presumptions in our own lives will be so grotesquely clear to those who look back at us.

Self-promotion and caricature

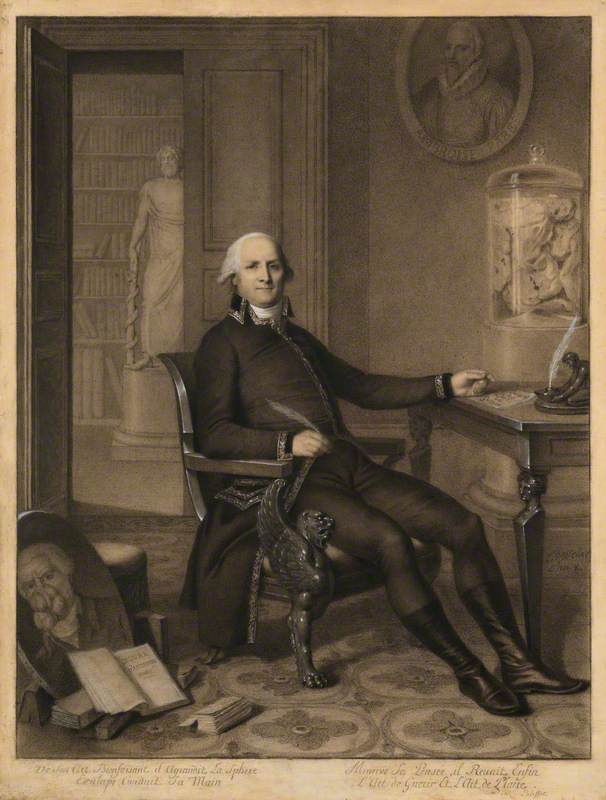

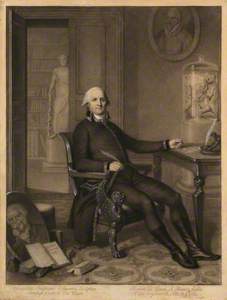

Has anyone ever seemed so lordly, so self-assured, so well-breakfasted as Ange-Bernard Imbert-Delonnes? This aristocrat of French surgery, who rose steadily through the ancien régime, the Revolution and the reign of Napoleon, looks out at us with a cool and level gaze, as he reclines in a chair – no, an imperial throne. Pierre Chasselat's chalk study might portray an Enlightenment patrician on his return from a Grand Tour, but one who has brought back some curious souvenirs. The statue in his library is not the usual Venus or Hercules, but Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. A jar on his desk holds something bulbous and grimly contorted, and a painting propped on the floor shows a man with a tumour obscuring his mouth.

What we see here is self-fashioning – the same thing going on in an influencer's obsessively curated Instagram feed. Imbert-Delonnes' reputation was built on his skill as a surgeon, and the portrait includes the tumours he excised from two leading French politicians. Just like an influencer, though, his overwhelming desire to impress might leave us wondering whether he's overcompensating. Imbert-Delonnes was well aware that medicine, and particularly surgery, were profoundly insecure professions. Practitioners may have aspired to learning, wealth and gentility, but they knew that patients had other things on their minds: the gamble of diagnosis, the drudgery of treatment, the inconstancy of cures, the shadow of death.

Incompetence, venality and pomposity were running gags in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century caricatures of physicians, surgeons and apothecaries – often little more than tradesmen, working with their hands and demanding payment for their services. The tubby, complacent apothecary in Thomas Rowlandson's publication The English Dance of Death seems in no hurry to treat the anguished woman sitting by his fireside. He's more taken with the jingle of coins, as Death stirs a milk-churn of poison.

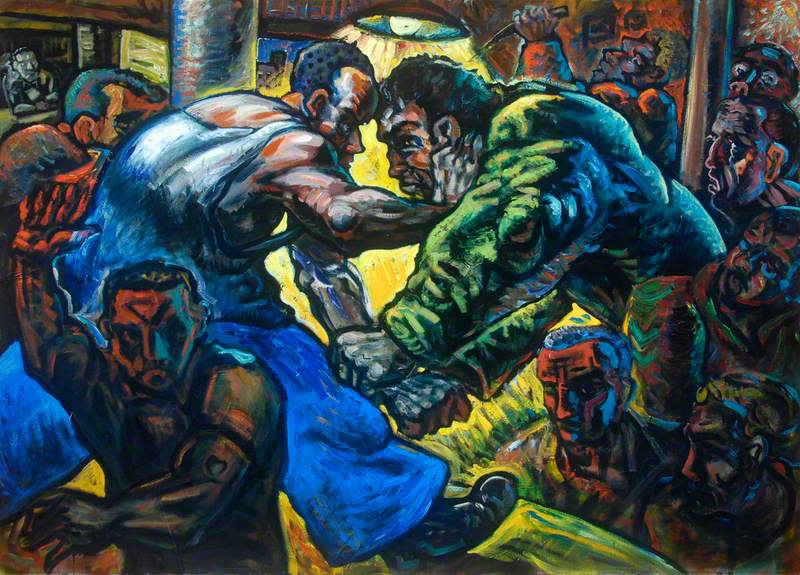

Through the nineteenth century, clinicians found fresh ways to reinforce their authority as learned gentlemen. New professional bodies set standards for qualifications and behaviour, while the disciplines emerging from laboratory science provided a compelling foundation for diagnosis and treatment. As the status of scientific medicine rose, and as its practitioners sought influence in government and society, medicine became profoundly entangled in the expansion of European empires.

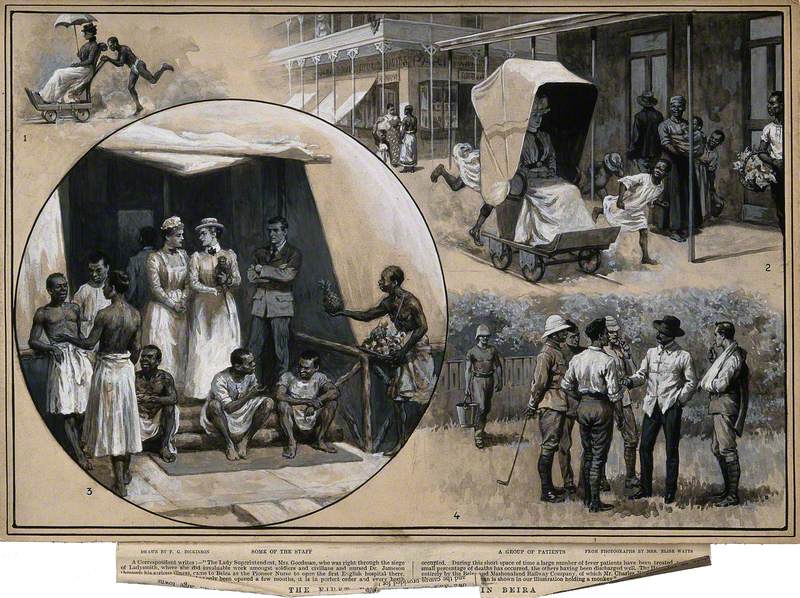

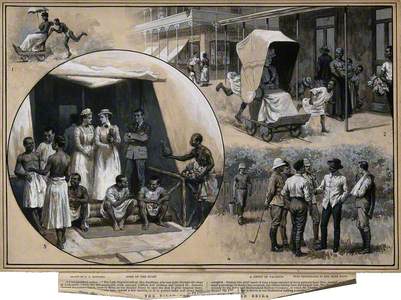

Specialities like tropical medicine had economic and military value, sustaining the health of settlers, merchants, troops and native workers. But they also featured prominently in moral and political justifications for colonisation. Far from seizing land and resources, European nations reassured themselves that they were humanitarians, bringing the benefits of scientific modernity to native peoples. During the Boer War, the newspaper illustrator F. C. Dickinson showed his readers the English hospital in Beira, Mozambique, along with its staff, patients and 'lady superintendent'. This is not, perhaps, the most overtly racist depiction of African people from this era – but note their status here, simply clad and physically lower than the white nurses and doctors they serve.

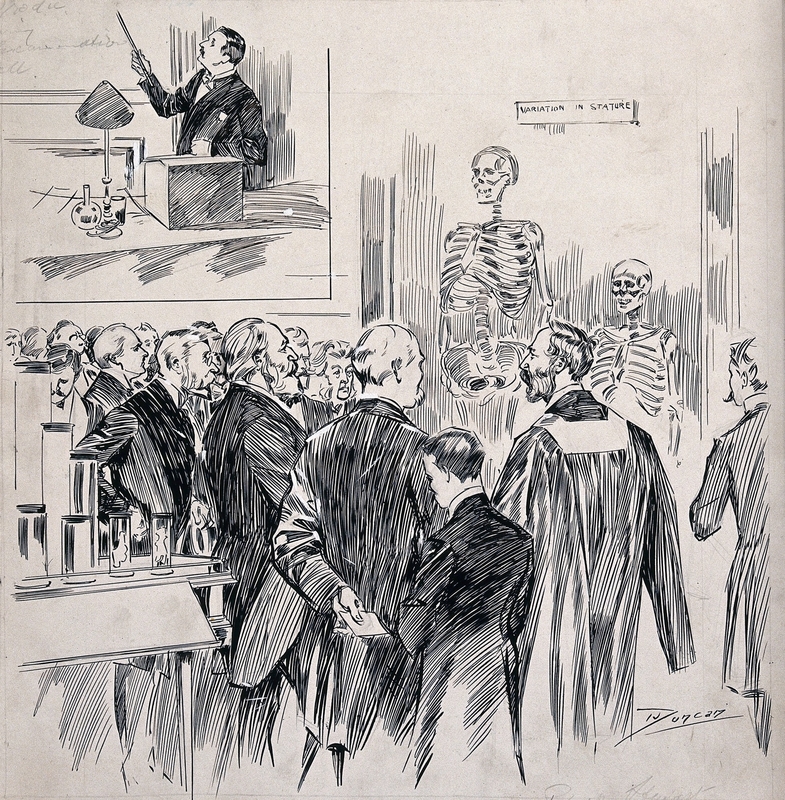

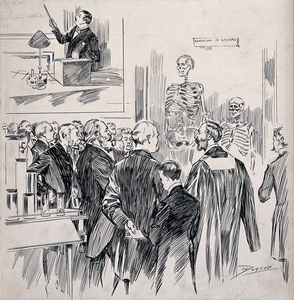

In the last year of the nineteenth century the Royal College of Surgeons of England marked its centenary, and another illustrator, James Allan Duncan, was on hand to record the scene. Beyond its value as an anthology of late Victorian hairstyles, Duncan's drawing captures how practitioners of the new scientific medicine were reinventing themselves. No longer mere conduits of ancient learning or anxiously aspirational entrepreneurs, they were now (they insisted) solemn, dignified men who embodied technical knowledge and Establishment authority. The turmoil of the twentieth century would bring new occasions for celebration and caricature alike, but this vision of medicine's power has proved remarkably enduring.

Richard Barnett, historian, broadcaster and poet

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Richard Barnett, The Sick Rose: Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration, Thames & Hudson / Wellcome Collection, 2014

Domenico Bertoloni Meli, Visualising Disease: The Art and History of Pathological Illustrations, University of Chicago, 2018

Peter Daston & Lorraine Galison, Objectivity, Zone Books, 2007

Monique Kornell, with Thisbe Gensler, Naoko Takahatake & Erin Travers, Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy, Getty Research Institute, 2022