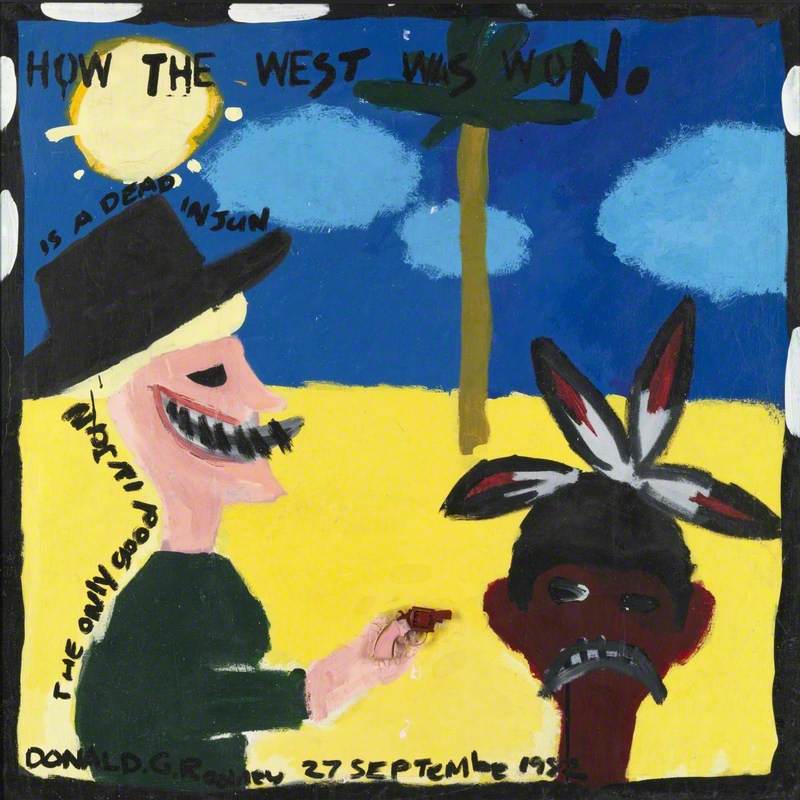

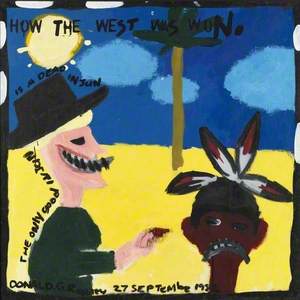

In Donald Rodney's How the West was Won (1982), a grinning cowboy stands on a plain and holds a gun to the head of a Native American. Running along the cowboy's back and over his hat are the words, 'The only good injun is a dead injun', a phrase attributed to Philip Sheridan, a Commanding General in the United States Army in the nineteenth century.

The painting's intentionally child-like style appears to recognise the ways in which these genocidal histories became fodder for children's books, cartoons, and games, particularly for young boys. The painted black and white frame around the image, meanwhile, gives the painting the look of a frame lifted from a movie reel.

How the West was Won was painted when Rodney was studying Fine Art at what was then Trent Polytechnic in Nottingham. It was there that he met Keith Piper, who inspired him to make work about the experience of being Black. Born to Jamaican parents, Rodney grew up on the outskirts of Birmingham, eventually following his BA with a Postgraduate Diploma in Multi-Media Fine Art at the Slade School of Fine Art, London, in 1987.

He began to show with Piper and other artists in a series of group exhibitions. How the West was Won appeared in one of the earliest, 'The First National Black Art Convention', held at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in October 1982. Other artists based in the West Midlands and associated with the group – who would go on to adopt the name the BLK Art Group – included Eddie Chambers, Marlene Smith, and Claudette Johnson; all questioned what Black art was and could be.

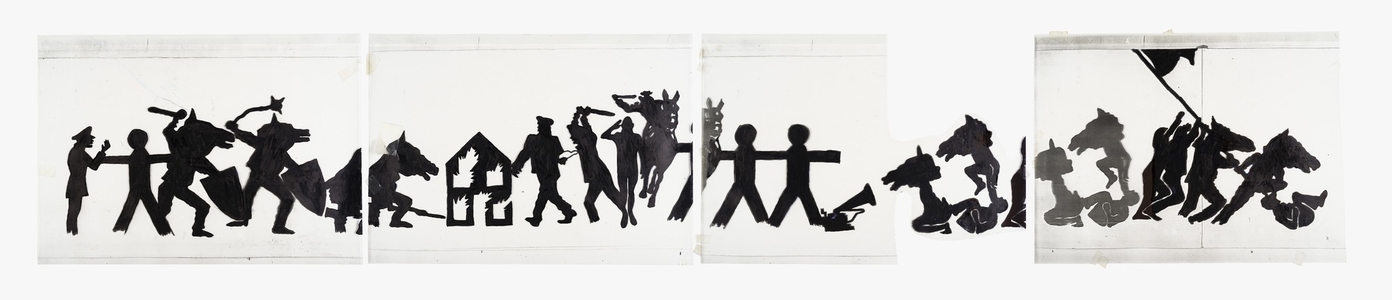

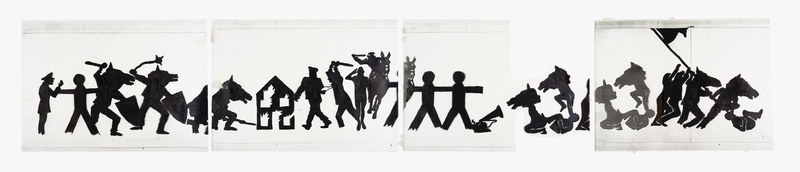

Preparatory Drawings for the Work 'Soweto/Guernica'

1988

Donald G. Rodney (1961–1998)

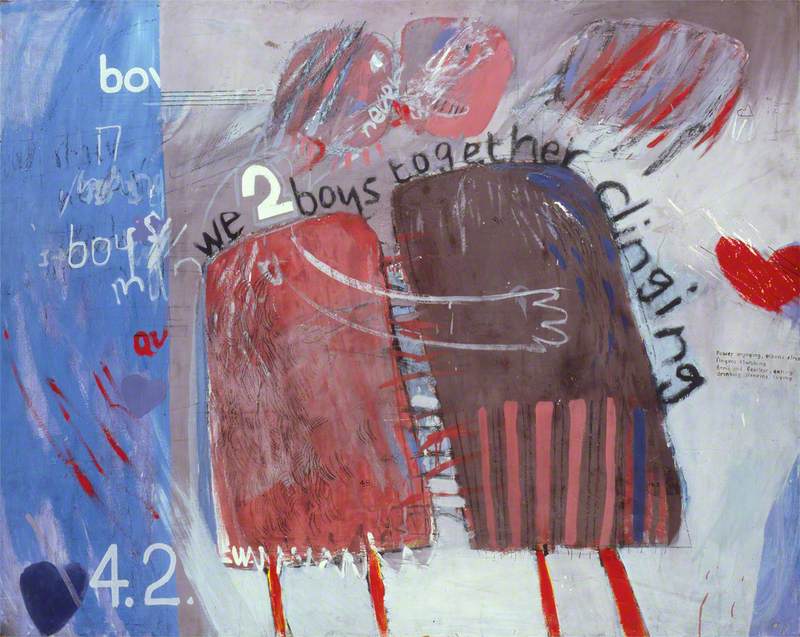

Though he was working in such a group, How the West was Won shows the breadth of Rodney's practice at this early stage. His work began with the experience of being Black and moved outwards from there. He returned to 'cowboys and Indians' and introduced even more expansive possibilities in the 1989 drawing Untitled ('Cowboy and Indian' after David Hockney's 'We Two Boys Together Clinging', 1961).

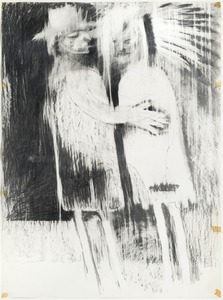

Untitled ('Cowboy and Indian' after David Hockney's 'We Two Boys Together Clinging', 1961)

1989

Donald G. Rodney (1961–1998)

The work references an early Hockney painting that utilised the poetry of Walt Whitman to make a coded reference to homosexual love.

Rodney transformed Hockney's lovers into a cowboy and Native American who meet in a moment of ambiguous, charged intimacy. The drawing is a testament to Rodney's close engagement with the history of art and his consistent forging of links between his own experiences and histories and those of others. These aspects of his practice can be traced in 'Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker', a survey exhibition that encompasses the majority of his surviving work that is currently open at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

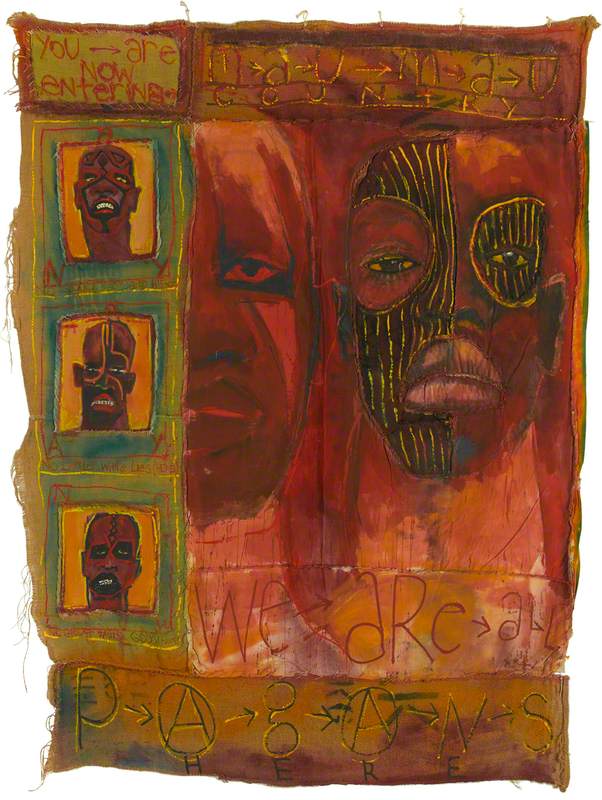

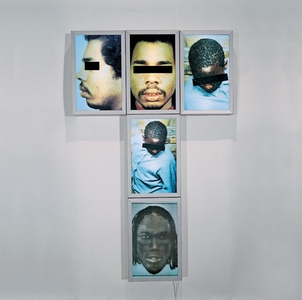

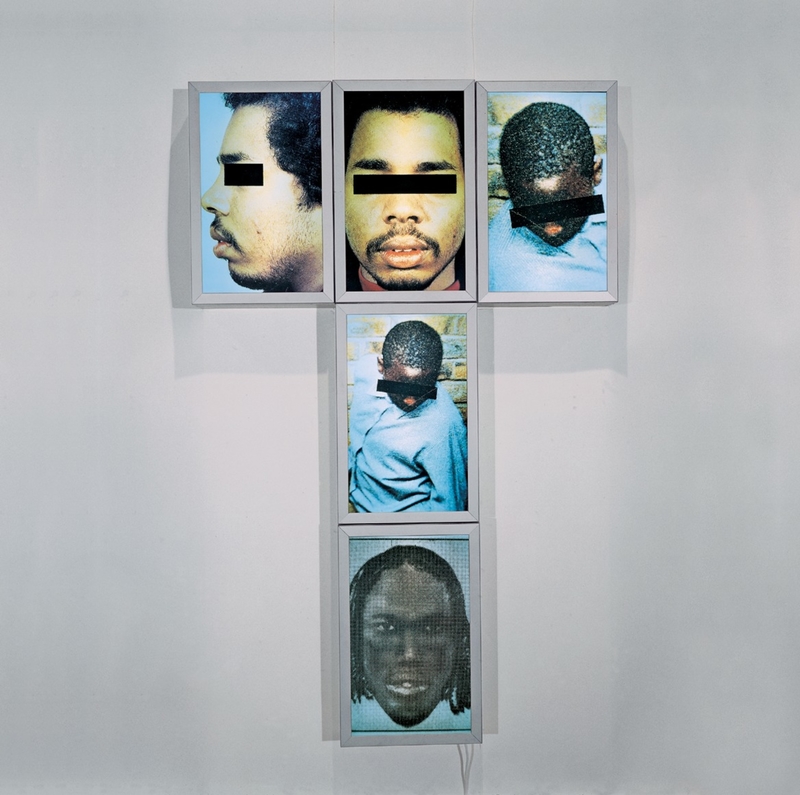

The interrogation of masculinities was not just a focus for Rodney's 'cowboy and Indian' works. In Self-Portrait: Black Men Public Enemy (1990), five lightboxes were adorned with five images of Black men, ranging from mugshots to an 'identikit' image issued by the police. The eyes of all the men, except for the 'identikit' figure, are concealed with black rectangles.

Self-Portrait 'Black Men Public Enemy'

1990

Donald G. Rodney (1961–1998)

In this way, the artwork references institutional and public constructions of the Black male as criminal or threat, and their dehumanising effects. It is named as a self-portrait even though Rodney does not physically appear, implying the all-encompassing power of such stereotypes to entrap young Black men against their will. Arranged in a 'T' formation and lit so that the portraits almost glow, the artwork also takes on the form of a crucifix and imbues these otherwise denigrated representations with holiness and care.

A year later, Rodney utilised lightboxes again to address the same kind of subject, turning now to a realm in which black masculinity found itself both celebrated and delimited – sport. In John Barnes and Mexico Olympics, both from 1991, Rodney reproduced famous photographs of acts of resistance and protest by Black sportsmen in response to racism.

John Barnes and Mexico Olympics

Both 1991, Duratrans prints on aluminium framed lightboxes with fluorescent tube lights by Donald Rodney (1961–1998), installation view, Spike Island, Bristol

These photographs were both illuminated and interrupted by the bars of the fluorescent tube lighting behind them, as if to reinvigorate viewers' relationship to canonical images of Black male resistance while also acknowledging the limitations imposed on them by sporting structures.

The following year, Rodney followed this thread with Doublethink (1992), consisting of a collection of sporting trophies, each bearing a plaque with a different generalisation about Black people. Here, Rodney mapped his interrogations of black masculinity and sport outwards, into the structures and stereotypes of society at large.

Doublethink (detail)

1992, trophies with engraved texts (glass cabinet, larger trophies and engraved captions with Eddie Chambers) by Donald Rodney (1961–1998)

Alongside these interrogations of Black masculinity, Rodney also responded to his own experiences with sickle cell anaemia; he died in 1998, aged 36, following complications associated with the disease.

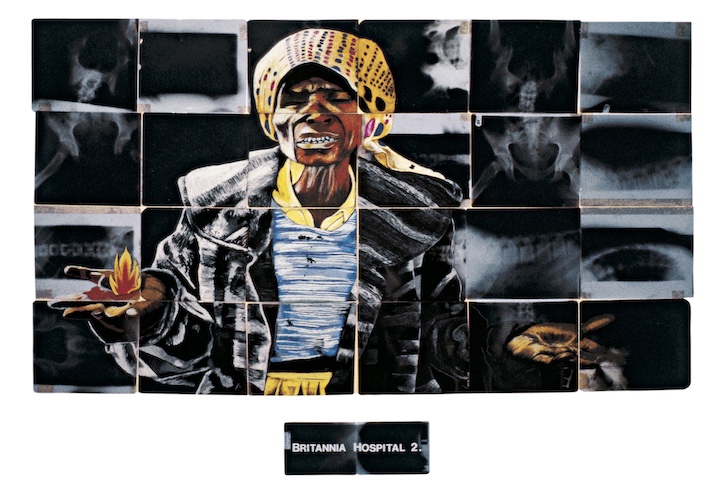

His Britannia Hospital series (1998) – made for Rodney's pivotal solo show at the Chisenhale Gallery in 1989 – was one of several instances in the late 1980s in which he utilised discarded X-rays, inspired by and acquired through his regular trips to hospital. The X-rays, like the later lightboxes, were gestures at seeing underneath or through surfaces, at looking differently.

Britannia Hopsital 2

1988, oil pastel on X-ray by Donald Rodney (1961–1998)

The Britannia Hospital works framed Britain as a hospital, and used typically disparate references from art history (Frida Kahlo), everyday life (Rodney in his hospital bed, an immigrant nurse), and Black struggle in Britain (Cherry Groce, shot and paralysed by police officers who entered her home in Brixton in 1985, alongside a member of the Met's Special Patrol Group) and internationally (the Soweto Uprising in South Africa in 1976). The hospital and its materials become a means of connecting individual sickness to the collective, of cruelty to care.

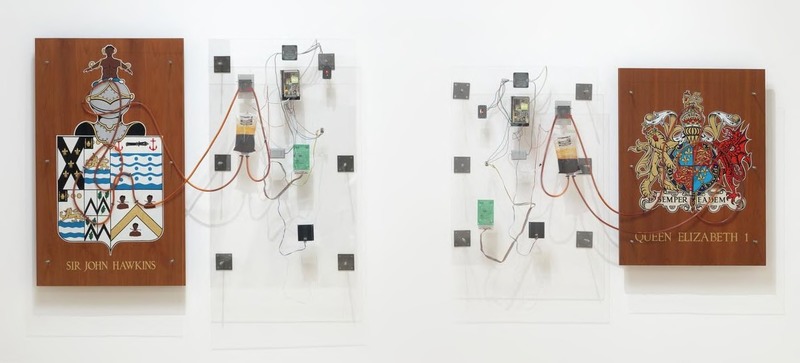

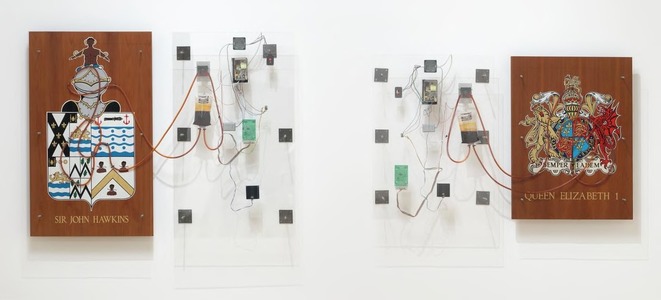

Sickness as something that debilitates but also reorientates, connecting you to individuals, communities, and histories also shaped 1990's Visceral Canker. Initially commissioned for a disused gun battery in Plymouth, the work consists of two enlarged coats of arms – one for Queen Elizabeth I and one for John Hawkins, who was from Plymouth and was the first English slave trader. The two coats of arms were linked by plastic tubes, through which Rodney intended to pump his own blood.

This intention was denied due to his sickle cell, which meant his blood was considered 'diseased' and a risk to others in ways comparable with attitudes to other blood-borne conditions at this time, namely HIV/AIDS. The result is a complex work of often uncomfortable intimacy and affiliation, between Rodney and key figures from British colonialism and slavery, and between Rodney and people with HIV/AIDS.

Sickle cell was also a vehicle through which Rodney explored more personal kinds of histories and connections, as in the photograph In The House Of My Father, in which he holds a tiny sculpture, entitled My Mother, My Father, My Sister, My Brother, both dated to 1997. The latter is a house, fashioned out of the artist's own skin, which was removed during one of his operations.

My Mother My Father My Sister My Brother

1996–1997

Donald G. Rodney (1961–1998)

The titles' references to family suggest the body as a site of inheritance and belonging. That house, though, is fragile, held together by pins.

In the House of My Father

(from an edition of three) 1996–1997

Donald G. Rodney (1961–1998)

Rodney knew that homes, and bodies, were vulnerable – from disease and from the police. Over the years, he drew on artworks by Richard Hamilton and David Wojnarowicz in his sketchbooks to reflect on this.

Rodney's art forged intimacies and affiliations. He worked from his position as a Black man with sickle cell anaemia, but allowed this to propel him into addressing and connecting disparate histories, subjects, and experiences.

A moving late work in Rodney's short career that encapsulates this is Psalms (1997). This features a motorised wheelchair, fixed with sensors so that it moves independently through the gallery, stopping if it meets viewers and objects. Made for his solo exhibition at the South London Gallery in 1997, the work poignantly came to stand for Rodney's absence at the opening because he was too sick to attend.

Rooted in his own decreasing mobility as well as the death of his father the previous year, Psalms traces the journeys of absent bodies – his own and his father's – and renews their presence in the world, endlessly. Here, the histories and experiences of race and disability that shaped Rodney's practice continue to circulate, meeting others and summoning the kinds of uncomfortable yet profound connections that were at the heart of his art.

Gregory Salter, Associate Professor in History of Art at the University of Birmingham

'Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker' is at Whitechapel Gallery from 12th February until 4th May 2025

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Eddie Chambers, 'His Catechism: The Art of Donald Rodney' in Third Text, 12.4, 1998

Alice Correia, 'Self-Portraiture and Representations of Blackness in the Work of: Donald Rodney' in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, 45, 2019

Richard Hylton, Donald Rodney: Art, Race, and the Body Politic, Bloomsbury, 2025

Richard Hylton (ed.), Donald Rodney: Doublethink, Autograph, 2003

Gregory Salter, 'Intertwining Histories in Donald Rodney's Untitled (Cowboy and Indian After David Hockney's We Two Boys Together Clinging, 1961), 1989' in Midlands Art Papers 2, 2019