In September 1989, Derek Jarman, aged 47, recalled his HIV diagnosis of 1986: 'I thought: this is not true, then I realised the enormity. I had been pushed into yet another corner, this time for keeps.'

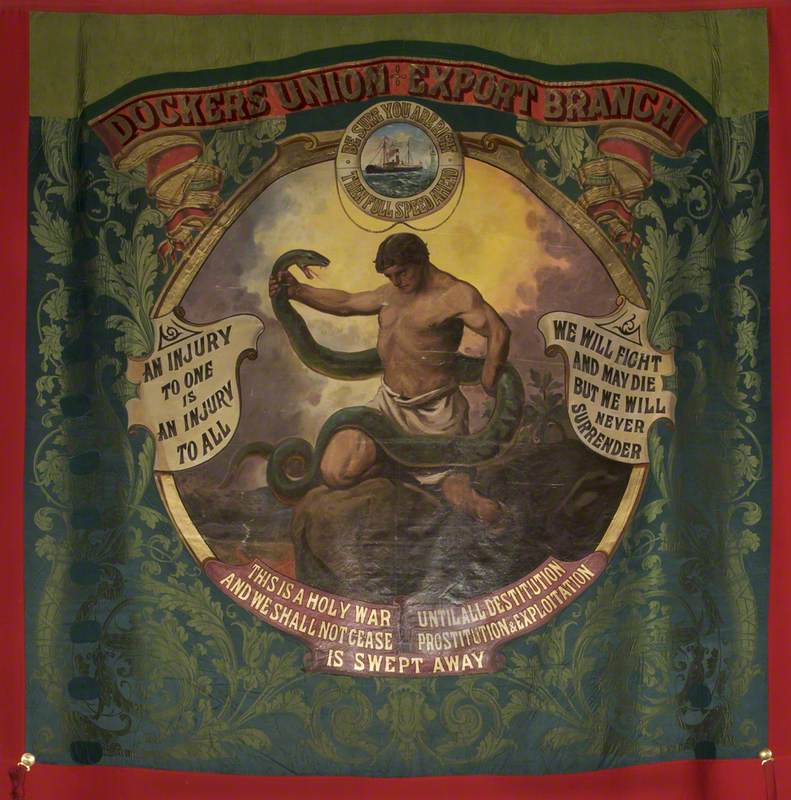

Pushed into yet another corner? Jarman was a teenager in the 1950s, one of the most oppressive decades for gay men in Britain, with pervasive homophobia, arrests, and a climate of fear and intimidation. From the beginning, then, Jarman was aware of the injustices of British society and extended this awareness to his practice of painting from the 1980s onwards, when he became deeply engaged in protest and politics. Many of these works, from the GBH series to the 'Slogan' paintings, have been brought together for the exhibition 'Derek Jarman: Protest!', at Manchester Art Gallery from 2nd December 2021 to 10th April 2022.

'For me to use the word 'queer' is a liberation; it was a word that frightened me, but no longer.' – Derek Jarman #DerekJarmanPROTEST is a major retrospective of one of the most influential figures in 20th century British culture

— MCR Art Gallery (@mcrartgallery) November 26, 2021

Opening 2 December, book your tickets now pic.twitter.com/I8GJDtWTyH

Born into a service family in 1942, 25 years before male homosexuality was legalised under certain conditions, Jarman often pointed to the importance of painting in his upbringing. He didn't want for a place at university and his father agreed to see him through the Slade if he went.

An awareness of his sexual orientation arrived early. Aged nine, he was caught cuddling his friend in bed at boarding school ('This wholly innocent affair was destroyed by a jealous dormitory captain'). Later referring to it as 'nascent', Jarman said: 'from then sexual encounters at school became furtive and unsuccessful'.

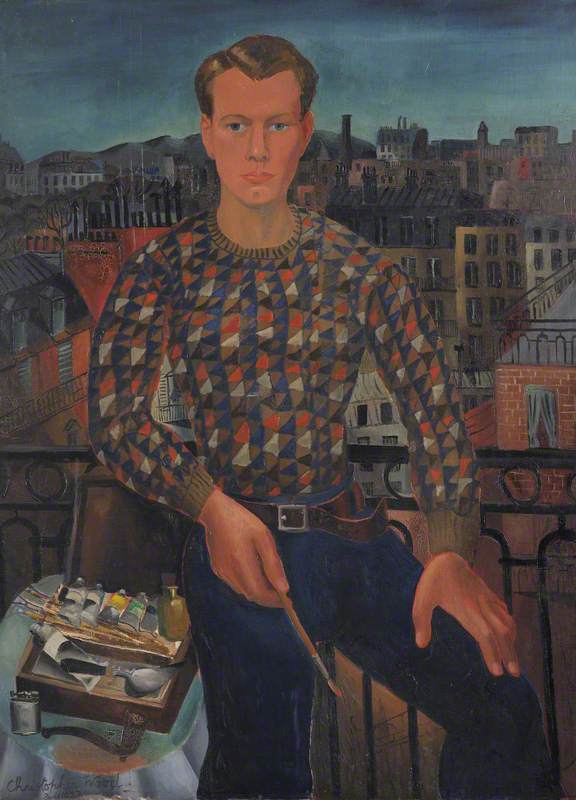

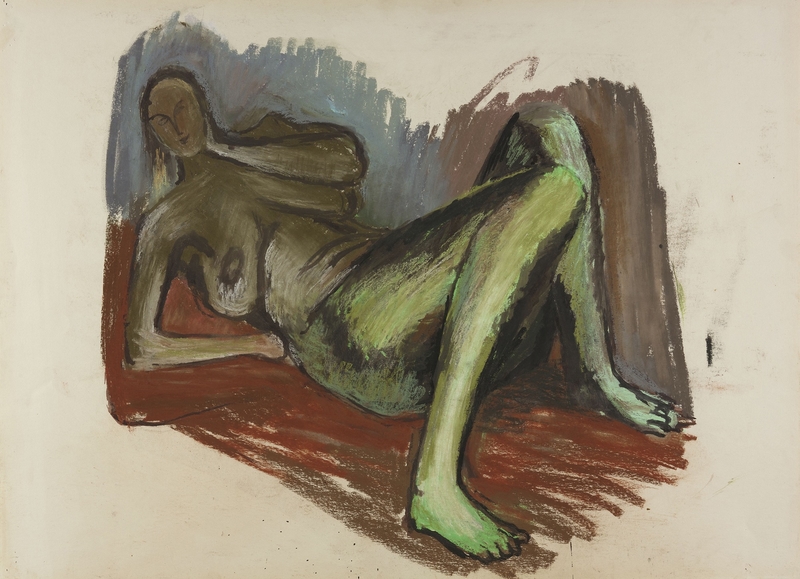

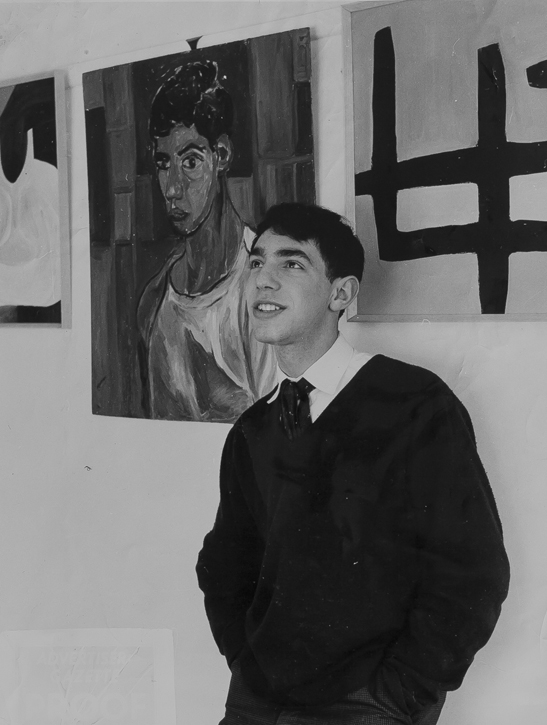

'From the Watford Advertiser 1960, with my self portrait painted 1959'

Recalling his first experience of discovering painting at Canford School in 1956, Jarman described it as self-defence. In Dancing Ledge (1984), Jarman expands on this metaphor: Almond Blossom by Van Gogh and wine bottles in Cubist still-lifes become 'weapons against the other order', and the school's art house is transformed into a 'refuge' against 'the bells, prayers, bullying... distilled into a distressing muscular Christianity'. Then 16, Jarman had scrutinised the British education system precisely, dominated as it then was by 'a systematic destruction of the creative mind', and deftly deflected its aggression towards painting.

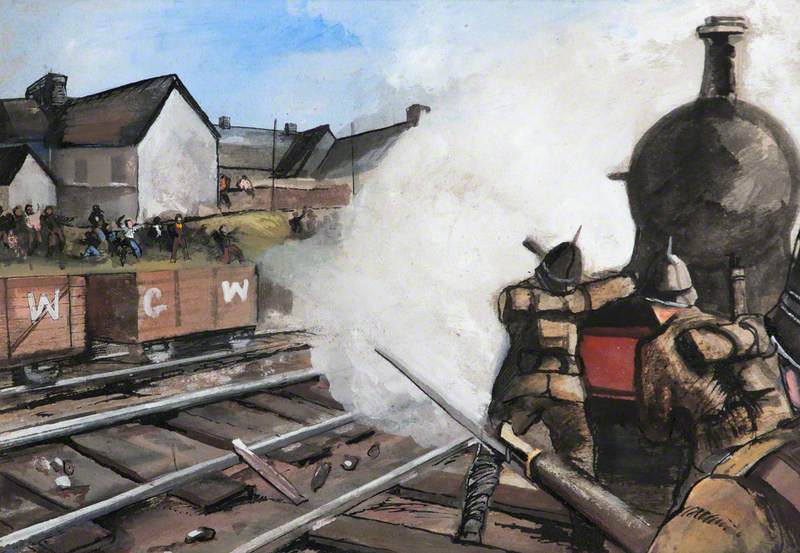

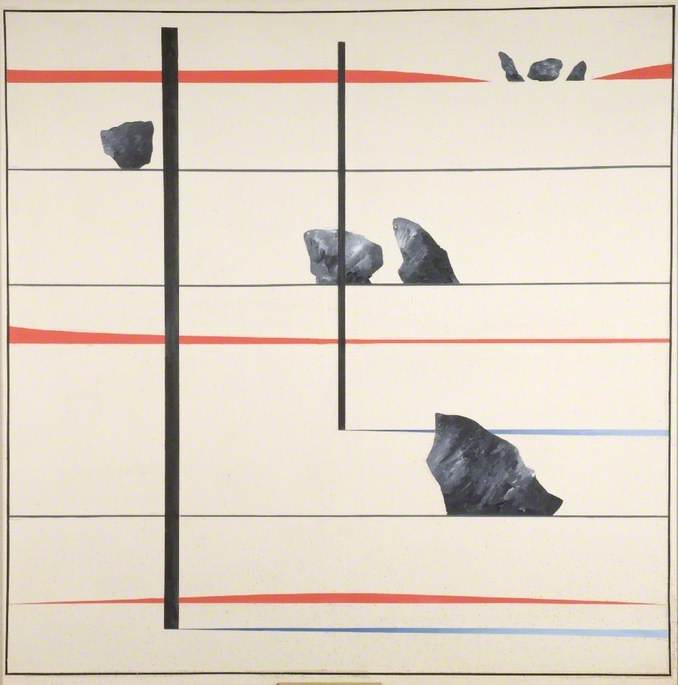

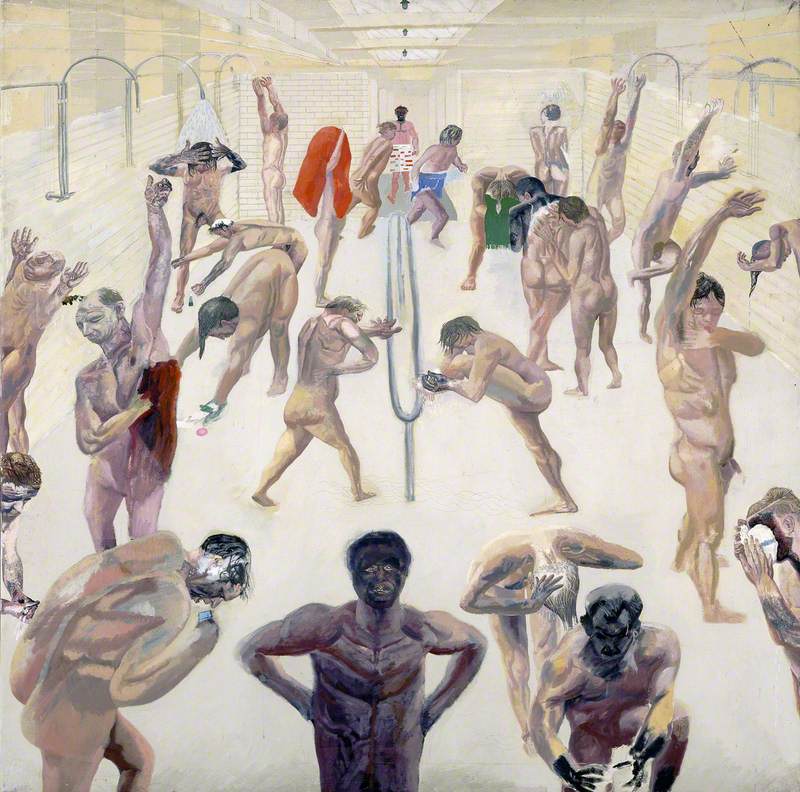

In the late 1970s and early 80s, Jarman's vision of a Britain that was no longer working prompted his GBH paintings, as if the assumptions and structures of the newly elected Conservative government reminded him of the images and feelings of anger and despair from his childhood. In painting about Britain under Thatcher, he didn't want to produce something 'too obvious'. His intention was not to commemorate or reanimate this period of history, but to create a space and an ambience for the viewer – to paint punk apocalyptic maps of Britain awash with burning reds and golds.

The GBH series, six large paintings created on specially prepared, canvas-backed newspapers, was produced for a show at the ICA in 1984, when he was 42, but, more importantly, they coincided with the publication of Dancing Ledge. The book allowed him to write about his sexuality, and let him be himself in a way he had not found easy in painting – the book would tell the story of Jarman since the libidinous excesses of the 1960s.

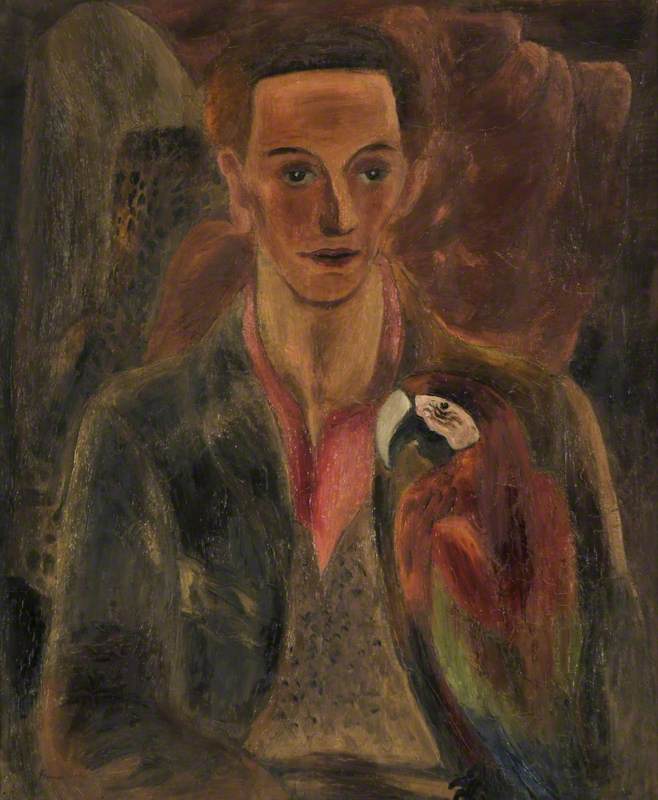

Sowers and Reapers

1987, oil & mixed media on canvas by Derek Jarman (1942–1994)

'My world is in fragments', Jarman writes at the end of his journal, The Last of England (1987), 'smashed in pieces so fine I doubt I will ever re-assemble them.' You might think that as soon as the diarist has shared that he contracted AIDS, his father died and he took up with a young man, he has nothing more to give, he has told everything. But Jarman's work proves the opposite, insisting that the bare fragments of freely given confessions are only the start.

'Paintings from a year', an exhibition in October 1987, tells a story of the whole span of Jarman's concerns across 132 canvases: AIDS, consumerism, the destruction of the landscape, American culture and private reverie. There are three paintings which are linked to, or arising out of his diagnosis with the virus, all overlapping in time: Afterlife in 1986, a small painting, almost an assemblage, about reincarnation; Smashing Times in 1987, a similar construction, black tar on celestial gold, depicts Jarman's handwriting scratched across glass: 'AIDS THE HETEROSEXIST prayer... SMASHING TIMES... VIRUS...'; and Apollo II in 1986, another assemblage, is almost exclusively concerned with the Greek god of health and plague.

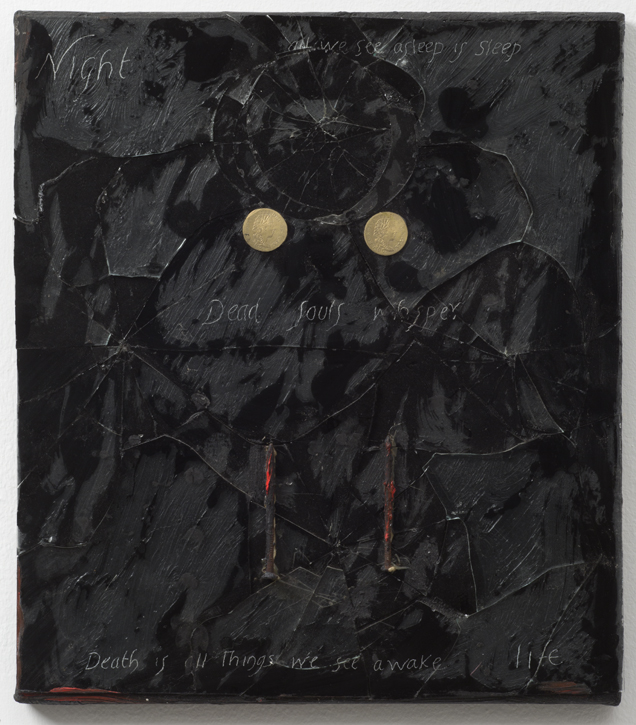

In these works, Jarman pressed gilded glass into black pigment, and engraved fragments of Heraclitus before smashing it with a hammer, fracturing the work at the point of its final creation. Along with glass and black oil, he introduced further objects to produce his marks and reference his illness. Impressing two gold coins into the paint, as in Dead Man's Eyes (1987), seems simple enough, but it is a more serious gesture than it looks, alluding to the terrible premonition of blindness Jarman had to reconcile with as his illness progressively worsened.

Dead Man's Eyes

1987, oil & mixed media on canvas by Derek Jarman (1942–1994)

These are the paintings where Robert Rauschenberg's influence on the artist first comes into view, where Jarman starts to see 'characteristics akin to film' in collage and construction and their 'ability to make literary ideas pictorial'.*

His relationship with Rauschenberg and his painting begins when Jarman is 22, and influences everything, from his choice to become a painter to how he feels about assemblage and collage. In their work, both drew inspiration from Andy Warhol, influenced, if not quite persuaded by, his insistence on the flat, hard-edge and repetitive character of silkscreen. Both believed in the power of their painting to work strategically within the mainstream to develop an immanent critique: for Rauschenberg, cold war politics, and for Jarman, the popular press.

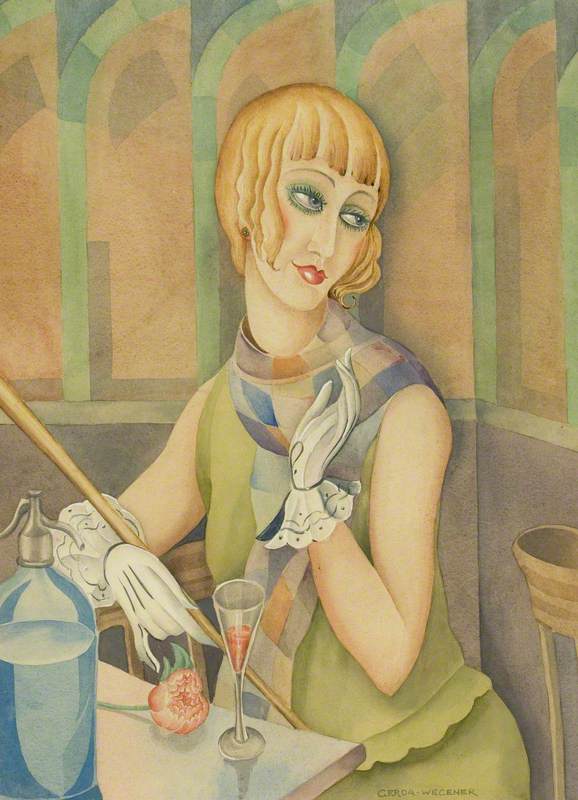

After a series of black assemblages circling around his father's death, Jarman turned his attention back to his childhood and his diagnosis with AIDS, writing the book At Your Own Risk (1992), which depicts homophobia Jarman faced living as a queer man. For Jarman, already outraged by the scarcity of the government's response to the AIDS epidemic, Section 28 – the final denial of his rights – was the spur towards a ferment of fury, despair and protest which would continue until his death. The memoir covers the years 1940 to 1991, collaging forgotten ways of behaving and speaking, weaving tabloid extracts with photographs and poetry to record a rich context of queer experience in the UK.

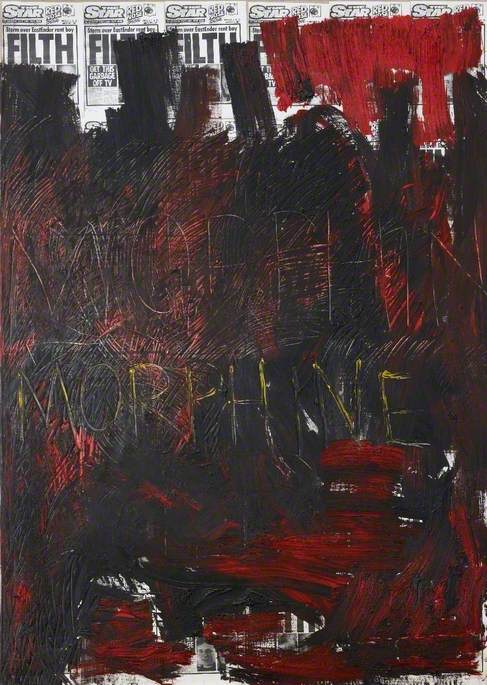

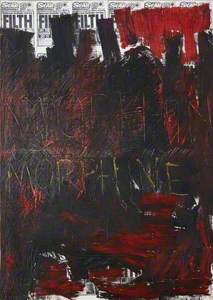

After At Your Own Risk, he painted a series of new works, completed in 1992, in which Jarman plastered photocopies of homophobic headlines in repeated rows across the canvas, covered them in swathes of paint, and finally, but most importantly, wrote messages of his own into the fluid impasto.

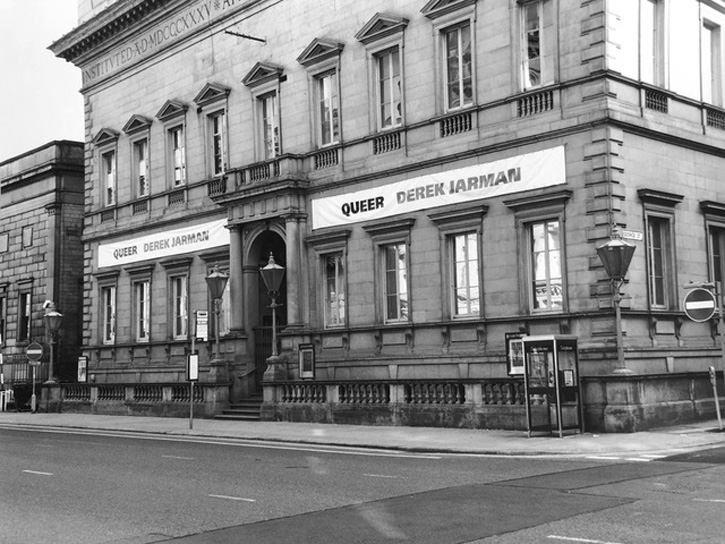

Exterior of Manchester Art Gallery, 'Queer' banner, 1993

He made an exceptional entrance with these works: in 'Queer', the show at the Manchester City Art Gallery in 1993, their reception was extremely positive, with four paintings purchased. Many of these large, lurid canvases are on display at Manchester Art Gallery as part of the exhibition 'Protest!'.

Jarman's use of newspaper becomes more political in the Queer series. His palette in paintings such as Blood (1992) and Morphine (1992) aggravates. The mood anger-inducing. The Queer series remembers, in all the ways Jarman's work has already remembered, by salvaging things, by providing testimony and evidence, by giving of himself so that others may feel less alone. 'I had to write of a sad time as a witness', Jarman says in the last lines of At Your Own Risk.

In the painting Letter to the Minister (1992), Jarman drew liberally from the English tabloid, transforming it for his own darkly funny and deadly serious purposes. The canvas is composed of multiple photocopies of the front page of The Sun newspaper covered in layers of yellow oil paint. Over a thinly washed patch of red, Jarman writes in charcoal a 'letter to the minister'. The newspaper headline ('Vile Book in School – pupils see pictures of gay lovers') alludes to the broader context of discursive pressure on homosexual lifestyles and its culmination in Section 28, and the crudely scrawled writing of the 'corrupted' fourteen-year-old schoolboy takes the place of Jarman, who connects the prohibition of homosexuality with the interdiction of Western culture: 'William Shakespeare, Francis Bacon, Allen Ginsberg'. He brings together aspects of Rauschenberg's work that Robert perhaps didn't imagine could be brought together: the blurred and overlapping images of his silkscreens; the highly gestural treatment of paint in his glossy black paintings; and the artist's voice scored across the canvas.

The experiments with newspaper and paint in each painting Jarman produces from 1992 to 1993 – when he retired from film-making and his illness worsens – all push against this division between the personal story and that of the times.

By 1992, when Jarman was writing his final diary, Smiling in Slow Motion, the homophobia in the Conservative party was known by all. Even in the late 1970s, however, Jarman felt he had some awareness of 'Thatcher's infantile regime'.** When Thatcher was elected in 1979, he immediately felt 'on board Battleship England – set firmly on course to OBLIVION'.

Margaret Thatcher's Lunch

1987, oil & mixed media on canvas by Derek Jarman (1942–1994)

Of all the paintings taking aim at the government's homophobia, Margaret Thatcher's Lunch (1987) may come closest to the most vitriolic. The bloodied knife and fork are presented as objects of violence and confront the viewer directly. They stand in stark contrast to the form of rusty metal in the tar eddied about them. Thatcher is never named, although the writing, scratched into the surface in a parody of her voice, lets us know who was in office.

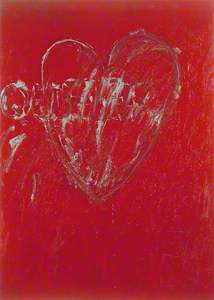

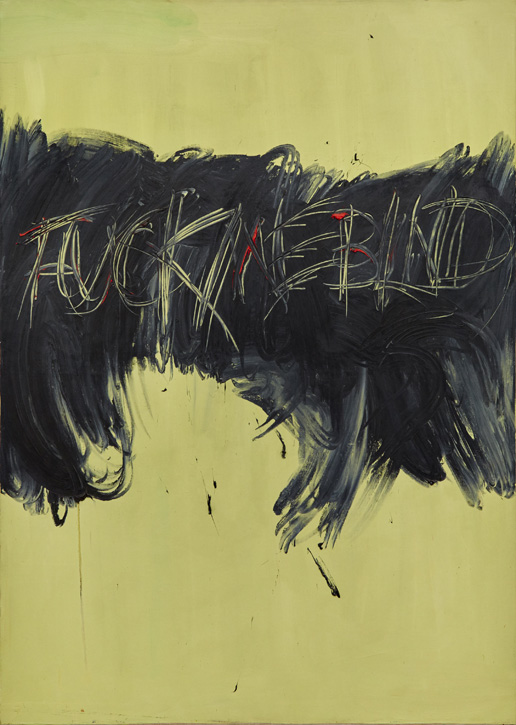

Fuck me blind

1993, oil on canvas by Derek Jarman (1942–1994)

Riffling through Smiling in Slow Motion, you'll see a great deal about the political group OutRage! and its distinction from the LGBTQ rights organisation Stonewall, and about 'outing', the practice of revealing a person's homosexuality which, for Jarman, was 'to open up discourse and with it broaden our horizons'. Given this, Jarman's lifelong effort to tackle oppression and 'fight against homophobia' reached an apogee with the Evil Queen series (1993), in which Jarman, perched in his old wingback chair, instructed his two assistants, Piers Clemmet and Karl Lydon, to fling paint at the canvas. Deciding the most important point was to comment on his illness, using a kitchen knife, he would inscribe the chosen word or phrase himself: 'Infection'; 'Death'; 'Fuck Me Blind'.

Death

1993, oil on photocopy on canvas by Derek Jarman (1942–1994)

The paintings evoke those of Jasper Johns (Jarman quotes Johns' stars and stripes more than once). We encounter the frenetic smears and concentric circles in Scream (1993) and Death (1993), a dark twist on Johns' well-known Target of 1955. Fuck me blind (1993) is a more austere take on some of Johns' work, which intimates invisibility or blindness, as in the murky Diver (1962–1963).

Infection

1993, oil on photocopy on canvas by Derek Jarman (1942–1994)

There are exceptions, of course, such as the thick impasto of Infection (1993), with clear allusions to the ravages of the AIDS epidemic abound: this painting reads 'INFECTION'. But the work has other focal points, in the series of furious white spots scribbled across the canvas, in the variation of touch, and it's possible to connect its subtle use of newspaper with previous works.

One thing is clear: in Jarman's late painting there is a semi-abstraction, in which what is exterior mingles with what is interior, often to the point of obscurity. 'They show the collision', Jarman says in Smiling in Slow Motion, 'between the unreality of the popular press and the state of mind of someone with AIDS'.

Matthew Cheale, writer, editor and art historian

* From the papers of Derek Jarman, notebook dated February 1964

**Passage deleted from the typescript of Dancing Ledge, in the BFI Jarman Collection II, Box 17

Further reading

Seán Kissane & Karim Rehmani-White, eds., Derek Jarman: Protest!, Thames & Hudson, 2020

Derek Jarman, At Your Own Risk, 1992 (reprint Vintage Classics, 2019)

Derek Jarman, Dancing Ledge, 1984 (reprint University of Minnesota Press, 2010)

Derek Jarman, Modern Nature, 1991 (reprint Vintage, 2017)

Derek Jarman, Smiling in Slow Motion, 2000 (reprint Vintage, 2001)

Derek Jarman, The Last of England, Constable, 1987