View just a handful of works by David Batchelor and you will soon appreciate his fascination with colour, especially the zingy hues found in urban environments.

Whether his Walldella series' vibrant rainbows or the pops of bright tones he adds to common objects, such as the cement mixer in Pink Pimp Mix (2006), the Dundee-born artist is on a long-term mission to explore how we respond to artificial colours that form such a fundamental part of our surroundings.

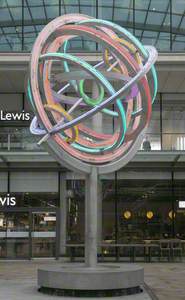

Based in London since 1984, Batchelor often relies on found or everyday materials for his sculptures, sizable versions of which appear in the new town of Milton Keynes and across London, including his neon-lit West Wing Spectrum (2003) at St Bartholomew's Hospital.

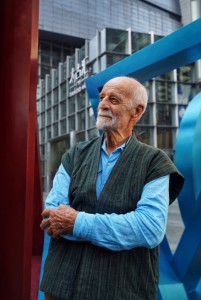

Work from across his career is currently on show at 'David Batchelor: Colour Is' at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, in the first large-scale survey of his output. Covering 40 years of creativity, including recent pieces made during the pandemic, Batchelor has had a large amount of input on the show. He explains on a call from his studio:

'I want the experience to be visually compelling, before people have to read the text. Then I hope the visitor comes away curious about what I've done, with perhaps that curiosity leading them to places that it has taken me and places that it hasn't.'

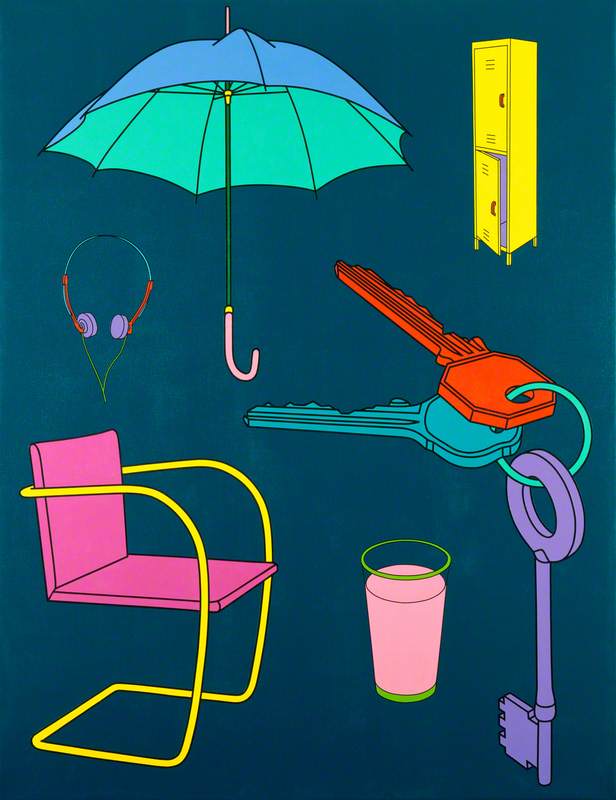

Installation view of 'David Batchelor: Colour Is'

Seeing works together devised over such a long period has been a remarkable experience for the artist, he admits. 'One thing you notice is that certain elements reoccur - motifs, devices, or just shapes and forms,' he says.

'You find yourself reusing them without being conscious of it, like the zigzag shape which is in one of the earliest works in the show and appears in some of my recent paintings. Between then and now, there are illuminated works that also use that stepping motif.'

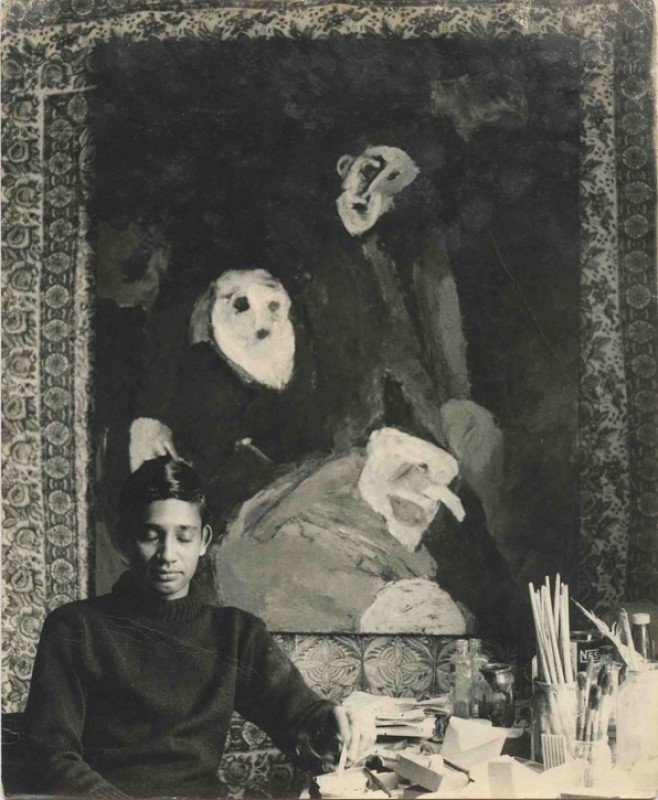

David Batchelor

Another recurring theme is the artist's use of shelves to place objects on, a strategy Batchelor sees as part of his attempt to make colour central to his work, 'to make a work that is about colour or somehow is colour'. This ambition dates back to 1992, when the artist broke with his habit of working in black and white to add pink to the front of a sculpture to successfully differentiate its front and back.

'I quickly noticed there was very little, if any, colour in my studio. There was very little colour in much contemporary art and there had been very little in my education, especially when I was taught at art college by conceptual artists, in fact, there was no talk about colour.'

Installation view of 'David Batchelor: Colour Is'

So Batchelor began to reflect on what he considered to be an 'avoidance' of varied hues. 'Colour is something we all experience, but in many respects, it's unfamiliar to us: we don't know what it is or why we see colour, what purpose it serves.'

He then muses more widely on the role of art, explaining his own particular drive: 'Artists want to invite you to look at something you think you know and to show it in a way that makes it unfamiliar. Art is nothing more than an invitation to look at things.'

Installation view of 'David Batchelor: Colour Is'

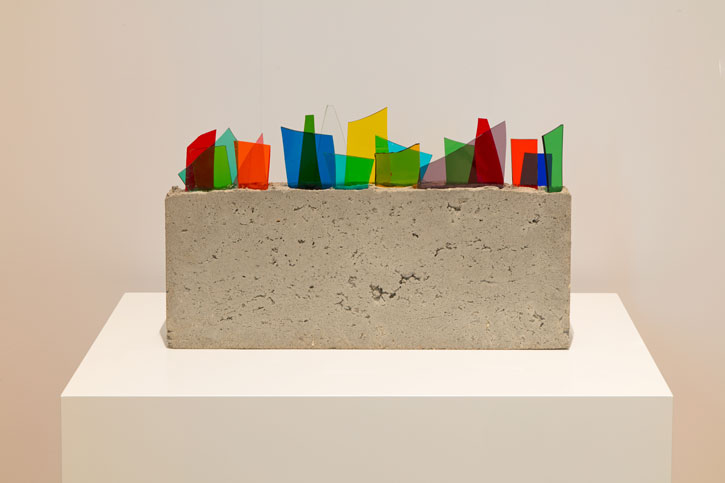

Rather than compile a catalogue for 'Colour Is', Batchelor has chosen to publish a book focusing on a particular strand of his oeuvre, joining a series that includes Flatlands (2013) and Found Monochromes (2010) that brought together drawings and photographs respectively. Concretos brings together many of the pieces devised since 2011 where the artist fixes colourful objects into low concrete blocks.

View this post on Instagram

Dating as far back as 2012 and inspired originally by shards of glass protruding from the top of a wall, discovered while strolling around a Sicilian seaside town, Batchelor has created so many 'concretos' that he has divided them into sub-genres (neo-cons, alt-cons and geo-cons among others). This is how he works, the sculptor explains, finding a device – objects in concrete, say – then working through its iterations and limitations.

'I find a provisional way of working and then I try to find the limits of it. How big can I go? How varied can the materials be? My blob paintings and colour-chart paintings are the same. Not everything works - there's quite a lot of failure, but that's always the case. Some things just don't do anything; they look inert, but to my surprise and pleasure, concrete is an incredibly adaptable theme.'

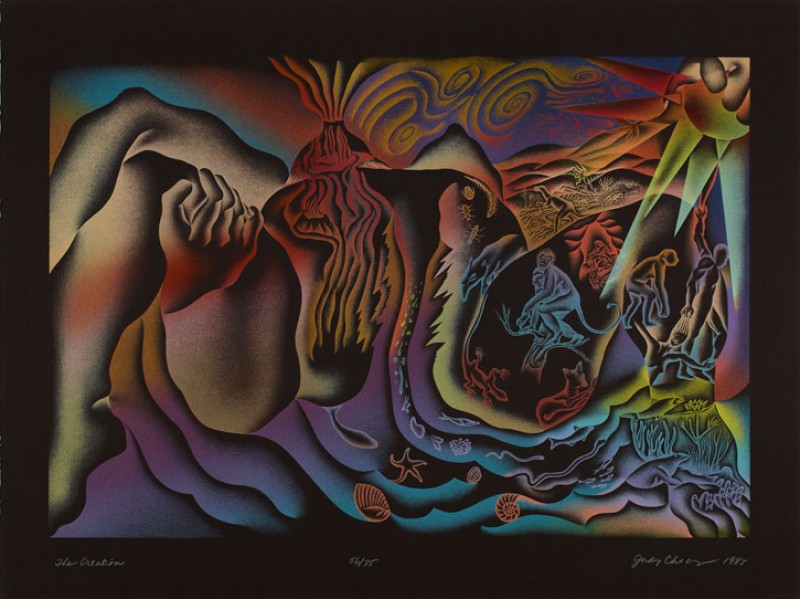

Inter-Concreto 29

2021, contrete, tape & Dibond by David Batchelor (b.1955)

Just as engrossing as the images in Concretos are Batchelor's essays, one of which examines the French concept of the flâneur, the urban sophisticate praised by the poet Charles Baudelaire that wanders the city's streets observing society. Walking is an important source of inspiration for Batchelor too, not only for the broken glass that inspired his concretos.

'A lot of things I've done have been inspired by what I've seen in the street,' he says. 'It's really important to see things in the world that aren't art and aren't even there to be looked at in any detail, things in the corner of my eye or the corner of the street. It goes back to Baudelaire: the artist has to attend to their modernity and filter those experiences into something.'

Batchelor remembers being inspired by a sight in São Paulo, Brazil: roadworks lit by bare lightbulbs inside plastic buckets. More recently, he has just returned from a holiday in Morocco where he was struck by the array of decorative steel work on doors in the Fez medina. 'I've been trying to imagine whether these shapes in bent steel, which would be painted, might work,' he muses.

Beyond his visual practice, Batchelor has explored the importance of colour in his much-admired book Chromophobia, which explores the aversion to its use in western cultures, or as the author puts it, 'since antiquity, colour has been systematically marginalised, reviled, diminished and degraded'.

Batchelor traces his wide reading and confidence with the written word partly to those conceptual artists that dominated his fine art degree at Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham (1975–1978), which led to a master's in cultural studies at the University of Birmingham (1978–1980), under the influential thinker Stuart Hall.

'Chromophobia was the legacy of both institutions. I read a lot of good stuff [at Nottingham] that stood me in good stead, but at the same time, I didn't make any work. We were writing polemics, encouraged to abandon art for activism of one kind or another, and I thought I was more interested in the politics of culture. One of my old friends from cultural studies said it was my book for that course and I think they're right.'

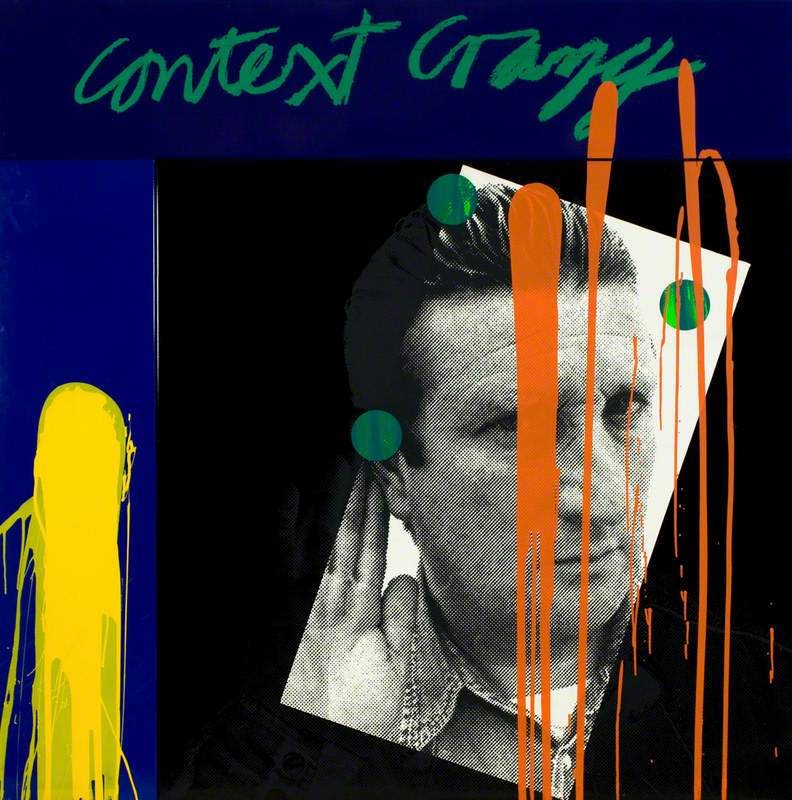

I Love King's Cross and King's Cross Loves Me, 5

2001

David Batchelor (b.1955)

Batchelor's art, though, is as much about playful trial and error as theory, something he highlights via a Samuel Beckett quote: dance first, then think. 'You've got to have that sense of feeling first, then following it up [with analysis]. I always think my main fan base is the under 12s, because kids don't have any problem going to look at my stuff.'

He illustrates this with an email from Compton Verney: a member of staff there overheard a six-year-old boy at the exit claiming that before seeing Batchelor's show their ambition was to be a cowboy, but now they wanted to be an artist. You get the sense this sculptor is as happy about that accolade than any high-brow reviews.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'David Batchelor: Colour Is' runs at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, until 2nd October 2022