There he is, peering out at us from a canvas painted 300 years ago by Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). He stands apart from his troupe, isolated in the brilliant white of his costume while the others huddle together behind him in a riot of sumptuous colour.

Pierrot, Harlequin and Scapin

c.1719

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

There he is again 60 years later, in his infancy as a rosy-cheeked and helplessly naïve child, his hands lost in the ungainly sleeves of his tunic.

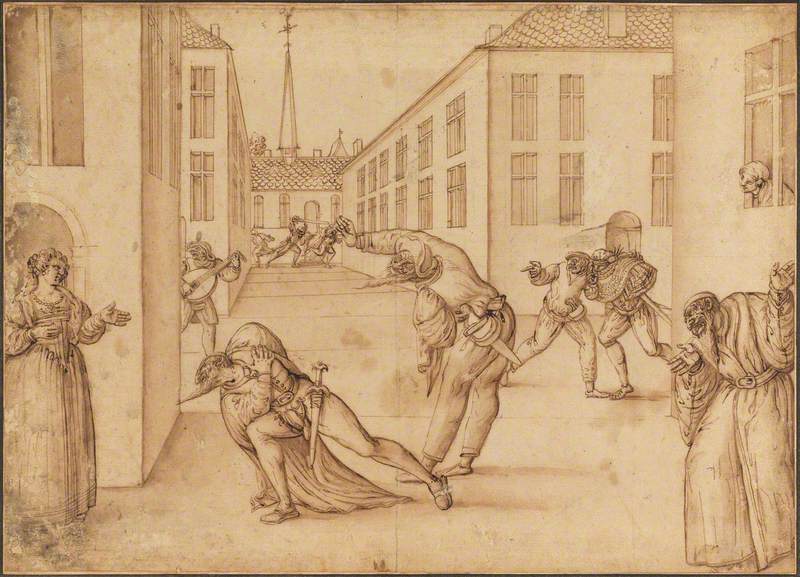

And again, hunched nervously over his helpers as he prepares to do battle with his old rival Harlequin, who in stark contrast appears relaxed and cocksure.

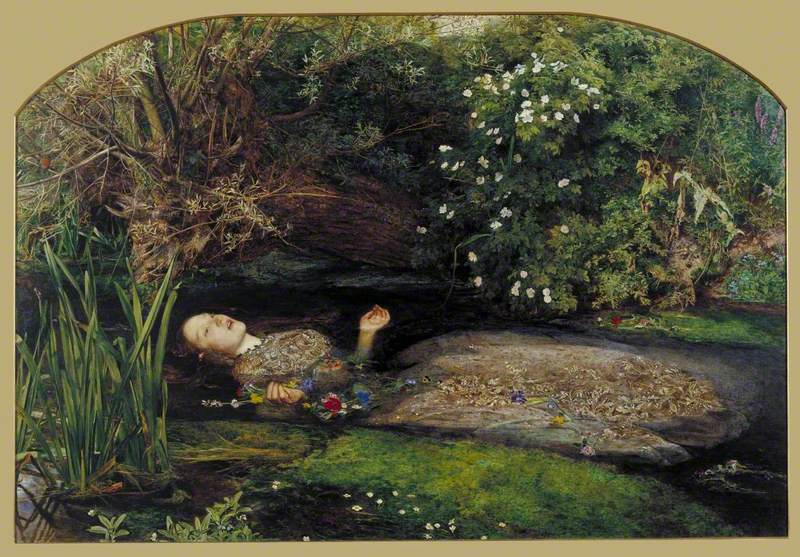

This is in the year 1857, the same year in which Jean-Léon Gérôme famously depicted the same event but settled his gaze on the inevitable aftermath that sees that iconic white costume stained with blood.

He's there in wartime Britain in Walter Sickert's 1915 painting, gazing hopelessly out at a poignantly invisible audience.

He's there in the aftermath of the Second World War, not the titular figure of John Armstrong's 1950 canvas but as a receding character in the background, fighting a losing battle against the cruelty of the elements with his umbrella.

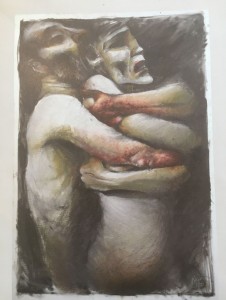

Such is the lot of Pierrot, visual art tells us. Always struggling, always alienated, always doomed to succumb to tragic defeat, he has suffered the barbarity of the world for three long centuries.

He didn't always have it so hard. Pierrot, an invention of the Italian commedia dell'arte troupes who delighted French audiences in Watteau's day, began life as a lazy, buffoonish stock character, the bumpkin foil to his fellow player Harlequin's ingenious trickery. Far from the star of the show, and far from the moonstruck figure who stumbles through the annals of western art, his simple ways were initially played for laughs.

It is unclear why Watteau saw something of the great melancholy that would come to characterise his outlook. It is difficult, too, to separate the truth from the fiction owing to the revival of interest in his Pierrot paintings during the heyday of Romanticism, whose proponents found this strange clown's curious alienation irresistible. The blank stare he offers his audience who came to see him fail, who came to laugh at the bawdy comedy, began to seem like an unexpected ally for a generation of artists and writers who increasingly viewed themselves as exemplary sufferers, at odds with an uncomprehending public.

The nineteenth century saw a wave of monographs written on Watteau, each one claiming (in an argument that has been consistently discredited by modern art historians) that the painter, depicting the revels of the sophisticated beau monde but standing essentially outside of it, identified with Pierrot as a symbolic analogue for the tragically estranged artist.

Simultaneously, Pierrot found a new lease of life on the French and British stages played by his greatest and most talented sponsors, Joey Grimaldi in London and Jean-Gaspard Deburau in Paris.

Both were strange, mercurial, and somewhat ghoulish figures in their own right. Grimaldi was known for inventing a set piece revolving around the discovery of a skeleton which reportedly caused some performers to literally die of fright, while Deburau was acquitted of murder after felling a child with a single stroke of his walking cane in 1836. The two actors responded to the Romantic temperament of their time and recast Pierrot as an eerie and existentially minded character who swept across the stage with a silent, somnambulist grace.

By the mid-nineteenth century, it scarcely mattered what Watteau's intentions had been in painting Pierrot. It was accepted, particularly among the French avant-garde of the day who battled against public conservatism, that Pierrot was no ordinary clown. To Charles Baudelaire, the poet with whose name the most sinister elements of the Romantic imagination are synonymous, Pierrot appeared 'pale as the moon, mysterious as silence, supple and mute as the serpent', a figure who has been 'degraded by his misery and the ingratitude of the public, into whose booth the forgetful world no longer wants to enter'.

The transformation was complete. In his poetically futile struggle, his newfound cruelty, his existential suffering and the ineffable grace of his pose, Pierrot was both the ally and rallying cry of the artist, the poet, the dandy.

Thomas Couture was among the artists to fall under his spell, not only depicting Pierrot before his fatal duel but also in a quiet moment alongside Harlequin.

The contrast between the two is instructive – Harlequin appears content with his newspaper while Pierrot stares sullenly into the smoke rising from his cigar. Behind him in the gloom, a poster advertising a masked ball is visible, while cluttered at the right of the canvas is a collection of empty wine bottles and a discarded top hat. Is the implication that they have returned from the ball? If so, the gaiety of the masses seems to have only intensified Pierrot's melancholy and, while Harlequin seems unconscious of his costume as he returns to normal pastimes, Pierrot seems to be all too aware that he cannot simply divest himself of his role now the party is over.

The friendship between clown and artist only intensified as the cultural pessimism and malaise of the fin-de-siecle dawned, and its most famous artists increasingly saw something of their own struggle for meaning in the confusion of modernity in Pierrot's brutal and arbitrary trials.

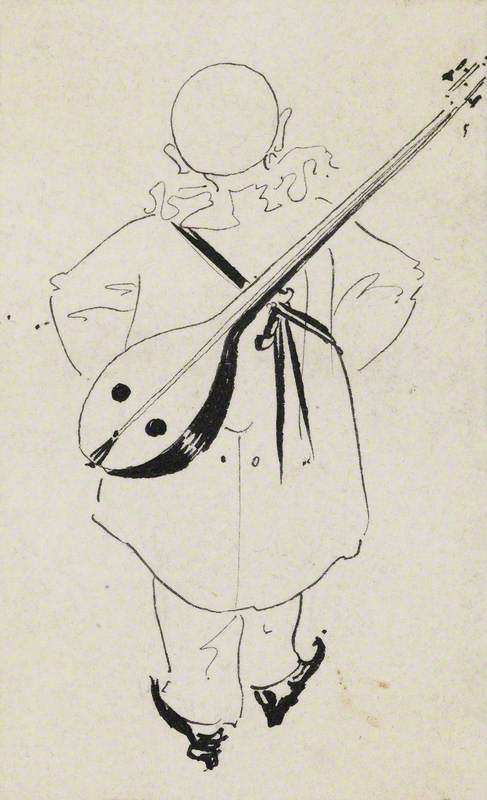

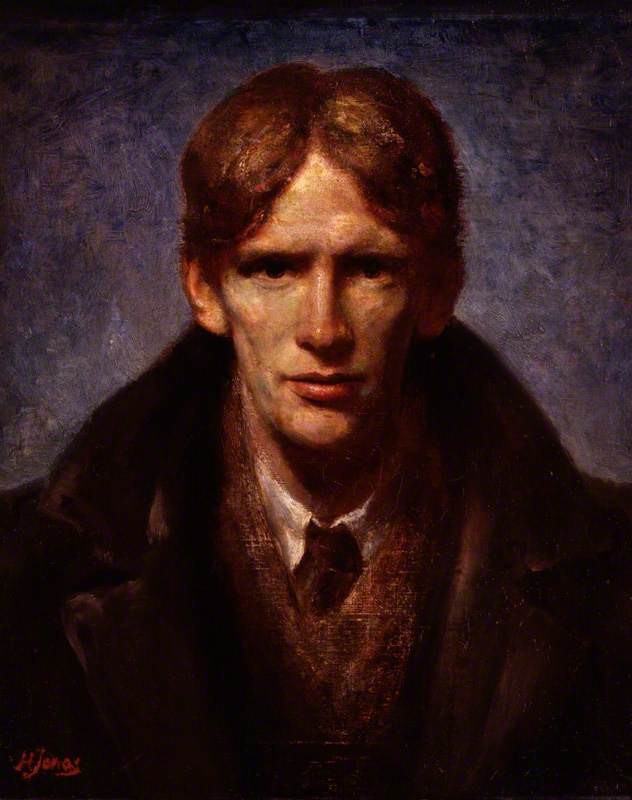

Perhaps the greatest, and most decadent, artist of them all was Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898), visionary draughtsman and decidedly tragic figure on account of his death from tuberculosis, aged just 25. Beardsley returned to Pierrot often in his short career. More often than not his Pierrots are alone, drifting in the blank white space that threatens to engulf them owing to the extreme economy of Beardsley's line. His 1894 Pierrot with Mandolin is a representative example, one that inverts the origins of Pierrot's entry into the world of visual art.

No longer looking out to his audience as Watteau's Pierrots inevitably did, Beardsley's figure has emphatically turned his back on them and has given up his mandolin – it is an image, perhaps, of the artist vilified by a philistine public refusing to play for them any longer.

And so he persisted, then as now – no longer the country bumpkin but the flour-faced victim of the modern age, articulating the existential angst of succeeding generations of artists through his mysterious silence.

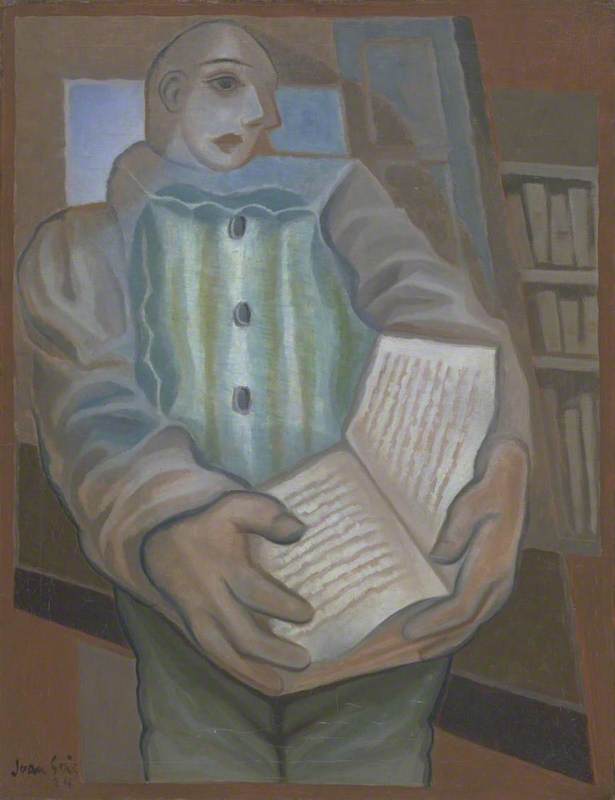

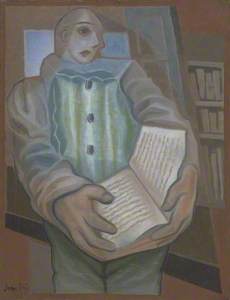

Despite his frequent appearances in the Rose Period works of Picasso, the elegant and romantic canvases of Pavel Tchelitchew, and the Cubist-inflected paintings of Juan Gris (1887–1927), for my money his most brilliant role in the twentieth century is in the oft-forgotten work of Ethel Wright (1866–1939).

Bonjour, Pierrot! – the cheeriness of the title appearing as yet another cruel joke – sees Pierrot once again staring at us with the same forlorn gaze he has perfected over the course of three centuries.

Tickled with a peacock feather by a laughing woman sticking her head through a window (she ought to be more careful – this is exactly the sort of teasing that unleashed Pierrot's occasional cruelty and brought Deburau's cane down upon an unfortunate boy's head in 1836), he appears not to notice, too consumed by his introspective melancholy.

Once again, he appears in front of a poster advertising a masked ball. Once again, he seems all too familiar with the fact that his is no mere costume to be taken up, but a symbol of the pain he endures. At least he has a dog for company now, its chained collar seeming to echo his white ruff and mirroring his own inability to escape the constraints of his fate. Knowing his luck, it's probably seconds away from biting him.

Samuel Love, MA student at the University of Edinburgh