Over the past two decades, various studies have shown that when in a museum or gallery environment people on average tend to look at a painting for somewhere between 15 and 30 seconds. It could

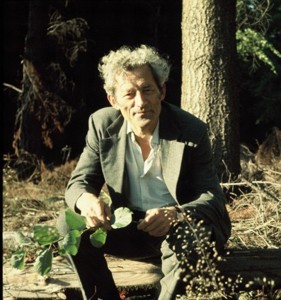

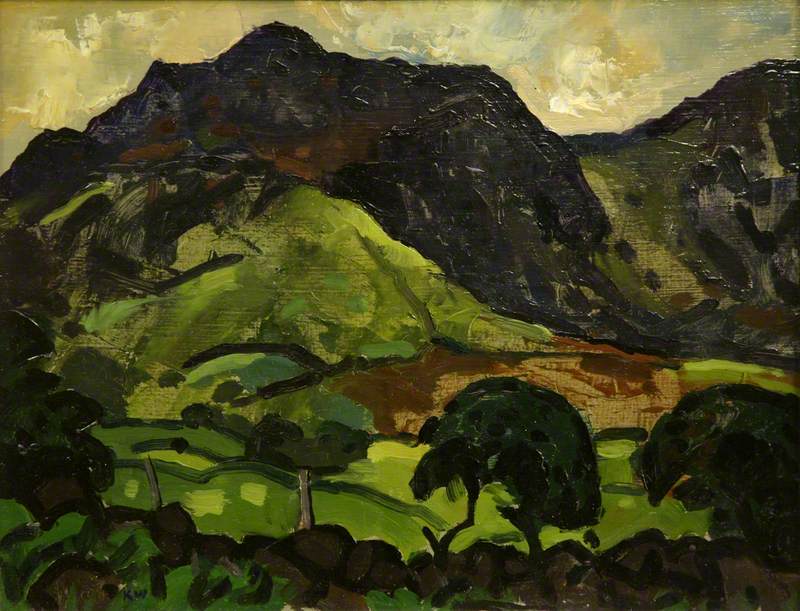

The landscapes of the late North Staffordshire artist Maurice Wade (1917–1991) fall into this category and more often than not leave a lasting impression for those lucky enough to see them in the flesh.

Maurice Wade was born on 31st March 1917 and his birth was registered at Wolstanton, Staffordshire. The only child of Joseph and Lucy Wade, he was born into modest circumstances, his father being a gas fitter. He served in the army during the Second World War, returning to North Staffordshire in the early 1950s and taking up a post teaching art at Churchfields Primary School in Newcastle-under-Lyme before becoming a full-time professional artist.

At the height of his painting career, Wade would exhibit at the Société des Artistes Français (where he was a gold medallist and exhibitor

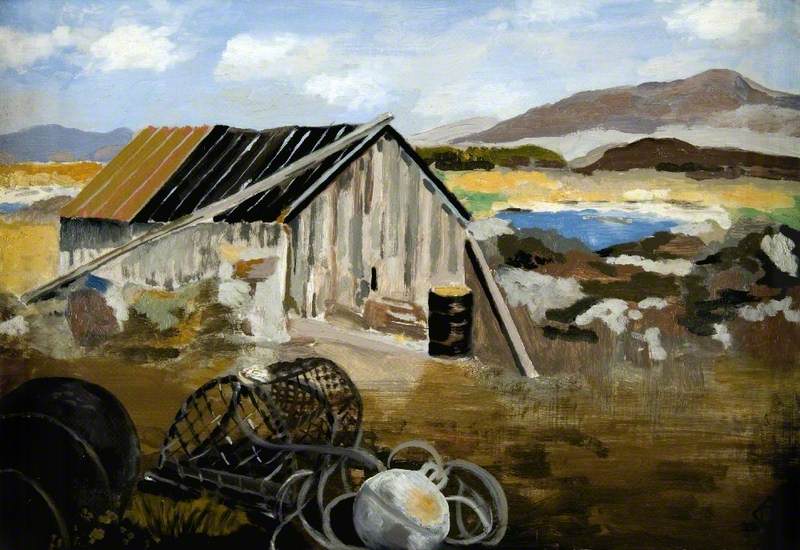

So, what is it about Wade's paintings of canals, disused factories, churchyards, hen runs and outbuildings of North Staffordshire that causes such astonishment to the viewer?

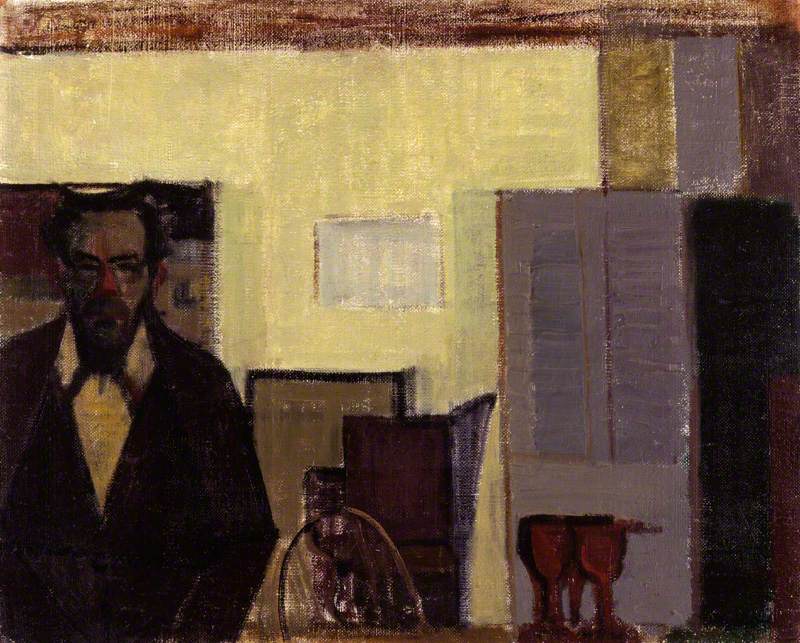

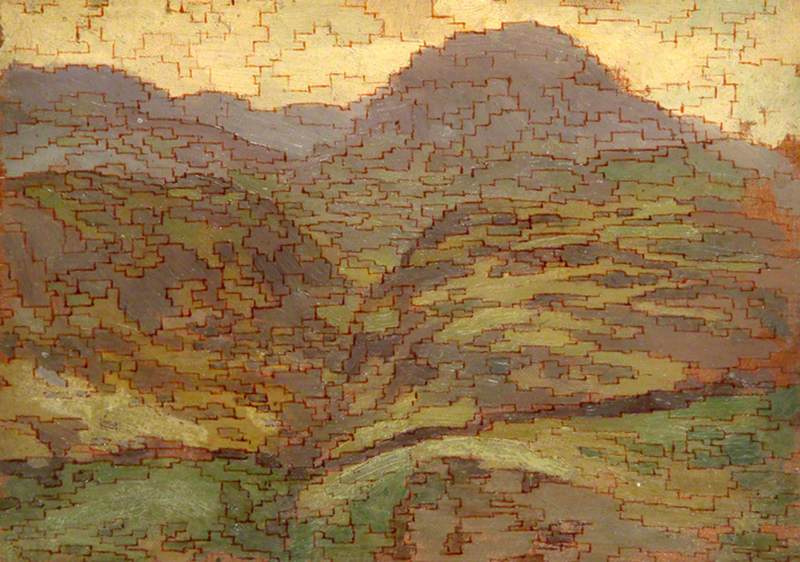

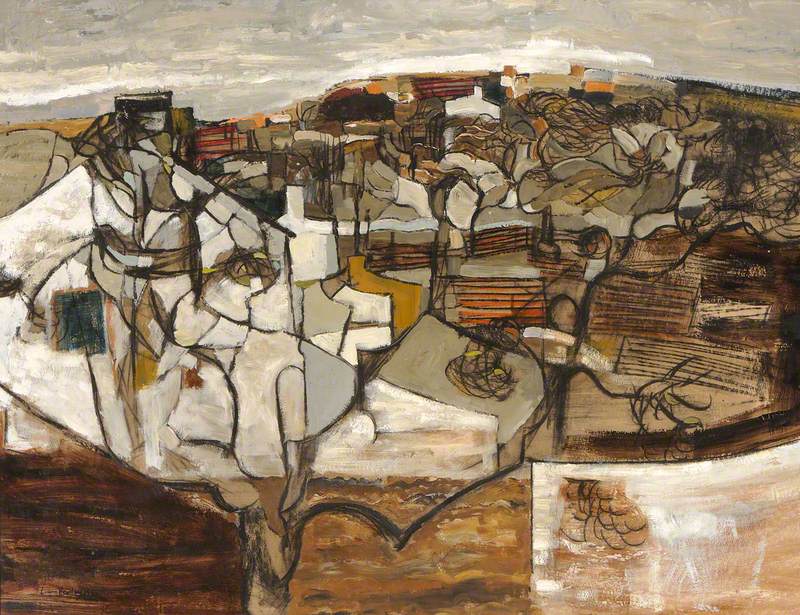

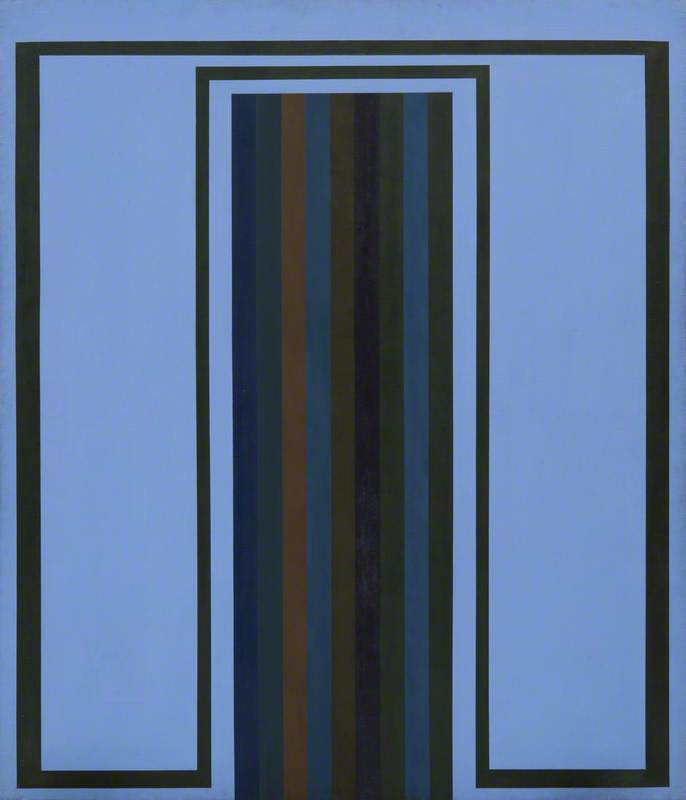

First and foremost, they are technically brilliant. Using a limited palette and painting solely with a palette knife, Wade consistently produced sublime and striking representations of geometrical structures and form that so often mesmerise observers of his work.

It is, however, Wade's approach to his subject matter that really sets them aside. These are that most rare of paintings, industrial landscapes with no hint of sentimentality, snapshots of time that are completely devoid of nostalgia. Paintings so cool, so still, so tranquil that had he introduced humanity into them, it would have very much detracted from the finished pieces. Indeed, Wade is quoted as saying 'I feel that man has no place in these pictures.'

Canal at Middleport is an excellent example of Wade's symbolic interpretation of a landscape. He produces a disengagement with the clutter and noise of the

In the landscape's sky, Wade, unlike most of his contemporaries, sees an open expanse of brilliant, spellbinding white. Likewise, his canal is a shimmering plate of glass, reflecting back every brick of the factory as if they were jewels. It is such an approach that can stop people in their tracks upon viewing. In simple terms, these are paintings that make you think and adjust to what you are seeing – a discombobulated brain catching up with the eyes.

Kitchen Chimneys is an earlier work from 1964 which again demonstrates Wade's technical brilliance. With no canal to produce striking reflections, Wade this time uses shadow to great effect on this painting of terraced 'backs'. While the subject matter may be ubiquitous, the finished landscape is a tour de force and one that draws the viewer in, almost trapping their gaze.

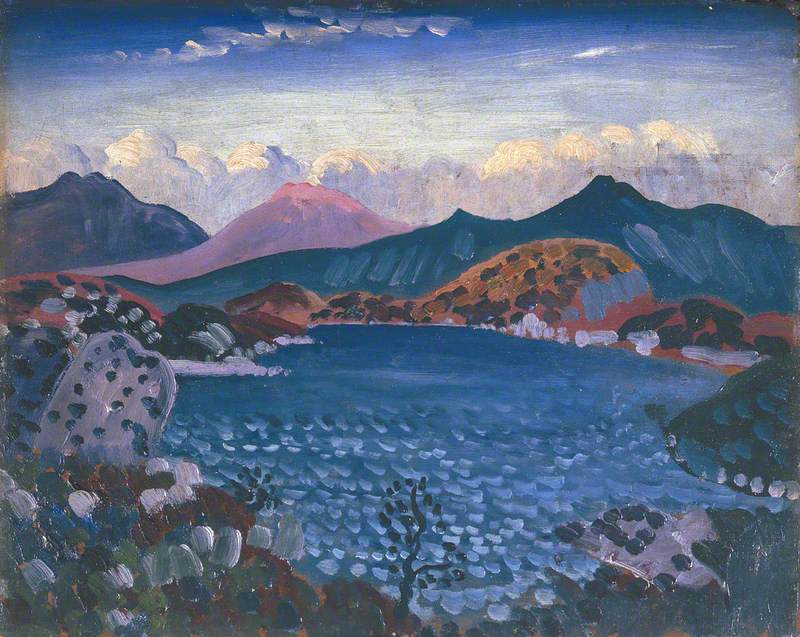

Influences are there to see or at least to be speculated upon. The stillness of Vilhelm Hammershøi's paintings is an obvious comparison along with the stripped-back London landscapes of Algernon Newton. Not bad company for Wade to be among.

So, in Wade, we have an artist whose paintings are worthy of more than a 30-second glance, and from our experience often engages viewers for a lengthy period of time, given the beauty and wonderment of his work. For those of you who wish to experience a selection of them, the Wedgwood Museum at Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent is highly recommended as they have a number on

Henry Birks, joint owner and director at Trent Art