Notoriously excluded from Giorgio Vasari's The Lives – a series of artist biographies – Carlo Crivelli has long been overlooked in favour of fifteenth-century household names, such as the Florentine Sandro Botticelli, or the Venetian Giovanni Bellini. Previously sidelined and misrepresented within the discipline of art history, his highly distinctive style resisted dominant pictorial ideals at the time, and his works defy stylistic categorisation.

One thing, though, is for certain: Crivelli was an artist who did not play by the rules. A new exhibition at Ikon – the first-ever UK exhibition dedicated to the artist – focuses on his highly experimental use of perspective, optical illusion and visual trickery. In his paintings we see a truly sophisticated and unique relationship between the material and the spiritual, the real and the illusory, to render worlds in which multiple realities seem to coexist.

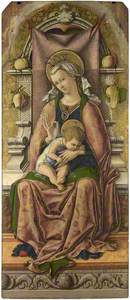

La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)

after 1490

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Born in Venice around 1430 to a family of painters, Crivelli worked as an artist and ran his own workshop in his home city until 1457, when he was imprisoned for six months for committing adultery with a married woman. Despite advertising his Venetian origins with his signature, Crivelli then permanently left Venice for Padua, where he worked in the workshop of Francesco Squarcione.

He then spent time in Zara, Dalmatia, before predominantly residing in the Marches, in the northeast of Italy. Crivelli was prolific during his lifetime, producing paintings for merchants, nobility, religious orders and confraternities, extending from the Apennine mountains to the Adriatic Sea.

Attention to material culture

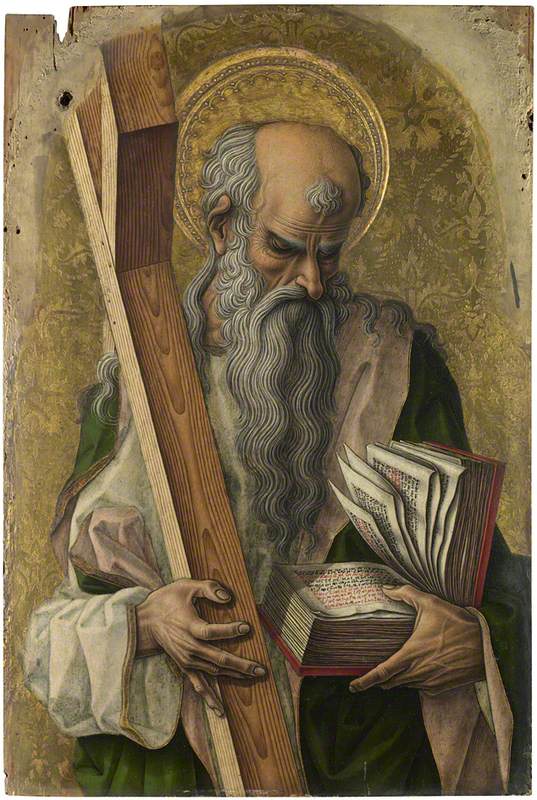

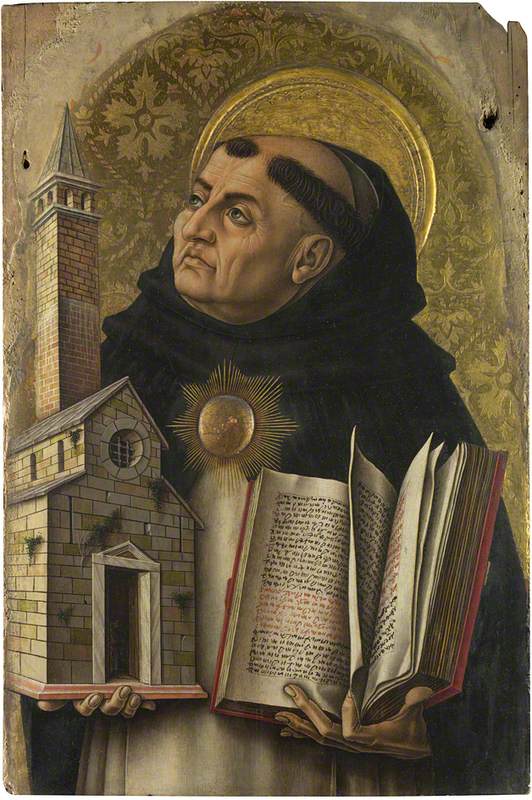

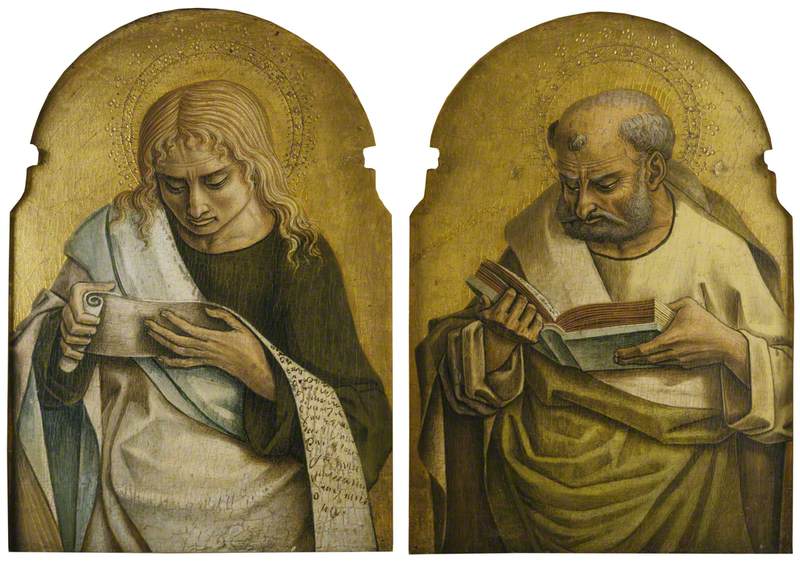

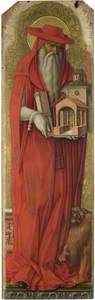

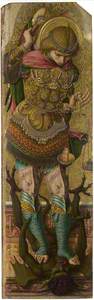

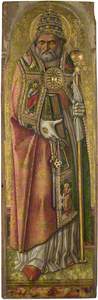

When you first encounter a painting by Crivelli, what may strike you is the sheer excess, owing to his use of opulent decoration combined with sophisticated illusive effects. His ornamental, gilded golden backgrounds, sumptuous renderings of perfectly ripened fruit and richly brocaded textiles recall works of the Late Gothic and the Northern Renaissance.

Predella of La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)

after 1490

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Crivelli is not shy about making his technical and artistic prowess known: his scenes are densely furnished with marble surfaces, elaborately carved and gilded thrones, and figures bedecked in precious jewels and gold leaf. Notably, Crivelli used pastiglia (or 'pastework') to an extent far beyond that of his contemporaries to work up details of his paintings – such as the clothing of holy figures – into three dimensions.

Spatial play and perspective

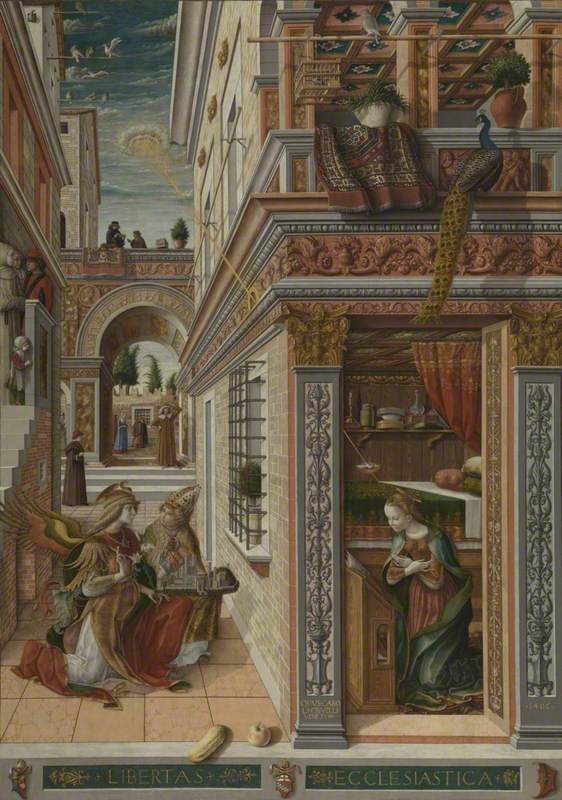

Another aspect that sets Crivelli apart from his contemporaries is his innovative use of perspective, particularly evident in his best-known painting: The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius (c.1486).

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius

1486

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Here, rather unconventionally, the vanishing point is located at the picture's left, rather than its centre. Crivelli uses perspective to create a deep sense of space within the painting, and as a result we cannot resist being pulled into it. This perspectival matrix is then disrupted by the gold ray of the Holy Spirit, which highlights the supernatural quality of Christ's incarnation.

In doing so, Crivelli is not only flaunting his artistic skill, but highlighting and exposing the limits of an imagined, pictorial system; a concept that is very modern, despite the fact that the work is over 500 years old. Here, Crivelli is revealing the mechanics behind his craft, and in doing so clearly points to an invented reality – something that most artists at the time were working hard to conceal.

Depiction of the everyday

Crivelli's interest in displaying everyday objects within celestial scenes seems to take influence from Netherlandish artists. Notably, he uses trompe l'oeil – an optical illusion – to trick the viewer into thinking the flat image is indeed three-dimensional. In doing so, Crivelli plays around with notions of weight and density, and we see domestic objects such pots and birdcages teetering on the edges of walls.

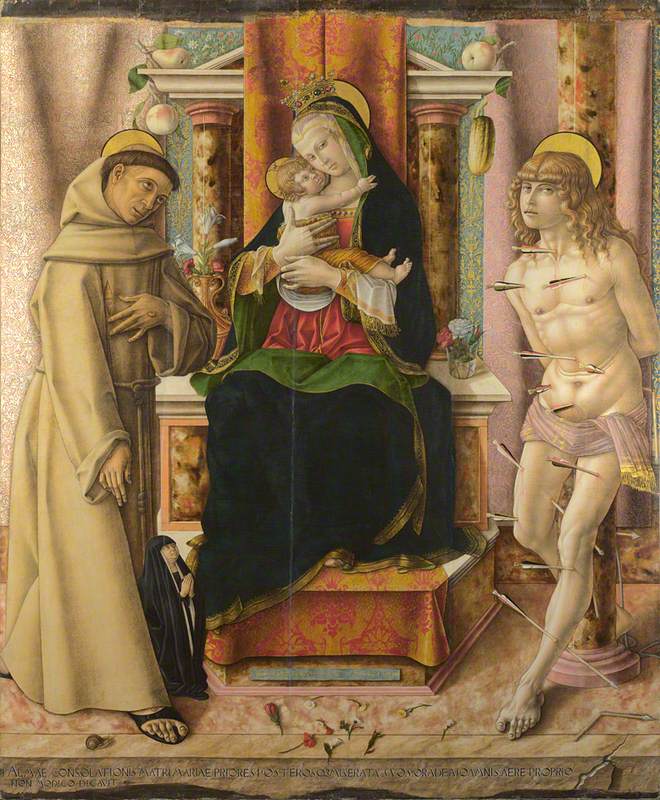

The Virgin and Child with Saints Francis and Sebastian

1491

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

This precarity grounds sacred scenes in the everyday, bringing them closer to the time and space of the devotee, or indeed, the viewer. Moreover, the richly patterned fabrics and Anatolian carpets, for example, clearly reference local traditions and trading, a nod to the merchant society in which Crivelli operated.

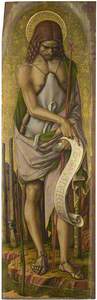

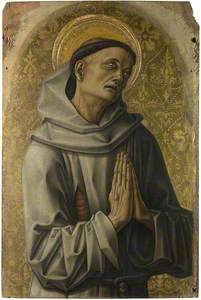

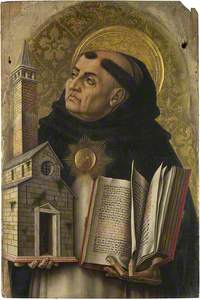

Crivelli's output consisted almost exclusively of altarpieces, intended to prompt spiritual devotion and contemplation. But how can an artist represent the unrepresentable? And how can they paint a figure that is at once human and divine? Crivelli's answer, perhaps, is to depict highly stylised figures.

In the Virgin and Child, c.1480, the Virgin appears almost manneristic, and her long, languid fingers verge on hyperreal, beyond physicality and human restraint. She heavily tilts her head and gazes outwards – but her eye line does not meet ours, as we may expect. There is an exaggerated artificiality here, reminding us that these figures are beyond our perception.

What's more, the infant Christ sits on a ledge, on which a carnation is attached with a blob of red wax, possibly alluding to the passion of Christ. The fact the flower seems to sit both 'on' and 'in' the picture suggests it is a votive offering, pinned onto the surface of the painting, reminding us of the multiple realities at play.

Playful Crivelli

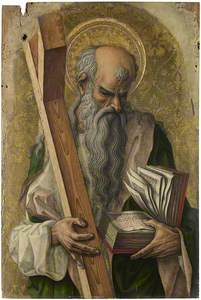

What we may find surprising is that Crivelli hid surprises and visual jokes in paintings depicting sacred events. Curious additions to holy images include animals such as snails and flies, the latter appearing time and time again. In Saint Catherine of Alexandria (c.1491–1494), a fly rests incongruously on a stone wall, to the left of the saint, almost as if it has landed on the picture.

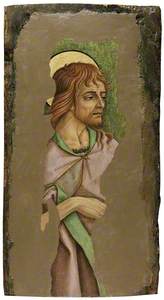

Saint Catherine of Alexandria

probably about 1491-4

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

At first glance, it appears oversized, but it is in fact scaled to the experience of the viewer, rather than the fictive space of the painting. Crivelli's signature addition is the cucumber, which can be found in celebratory garlands adorning the Virgin, or balancing on a ledge and projecting out towards the viewer. There are multiple symbolic readings into the inclusion of this humble vegetable, but you can read into it what you will.

Nothing is as it seems

The surreality of Crivelli's paintings questions artistic representation, and even the act of looking itself. In The Vision of Blessed Gabriele (c.1489), a festoon of fruit tied by two thin cords appears to hang directly from the frame of the picture, suggesting it exists in a liminal space, between two worlds.

The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele

probably about 1489

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Furthermore, the shadows on the sky – cast by the swags of fruit – bring us back to the present moment, pointing to the painterly aspect of the picture, and reminding us that we are looking at a flat surface – momentarily un-tricking us.

In Saint Mary Magdalene (c.1491–1494), the feet of the saint rest on the edge of the parapet on which she stands, extending beyond the picture plane, blurring the lines between where the painting ends, and where our reality begins.

Saint Mary Magdalene

probably about 1491-4

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Crivelli's works have the unique, mesmeric ability to cut across time and space, and as a result, they belong just as much to the present as they do to the past. At a time when we are inundated with images, we often need to question what we see in order to get to the true meaning behind it. In a similar vein, Crivelli's pictures require active, engaged looking – and even so, the more you look, the less you seem to know. Whilst looking, your eyes – or the artist – may still play tricks on you.

Melissa Baksh, art historian and freelance writer

The exhibition 'Carlo Crivelli: Shadows on the Sky' is at Ikon Gallery from 23rd February to 29th May 2022