The V&A Museum of Childhood has a wonderful historic art collection celebrating what it is to be a child. Although, like all museums, much is in storage, what is on display rewards hunting out and viewing. As of April 2019, all the works discussed are currently on display in the museum which is free to visit.

The first two works are a very good summation of the diversity of childhood. To be a child is the freedom to play, to imagine. The opposite of play is direction – the enemy of play. Let's begin with play and imagination fully engaged.

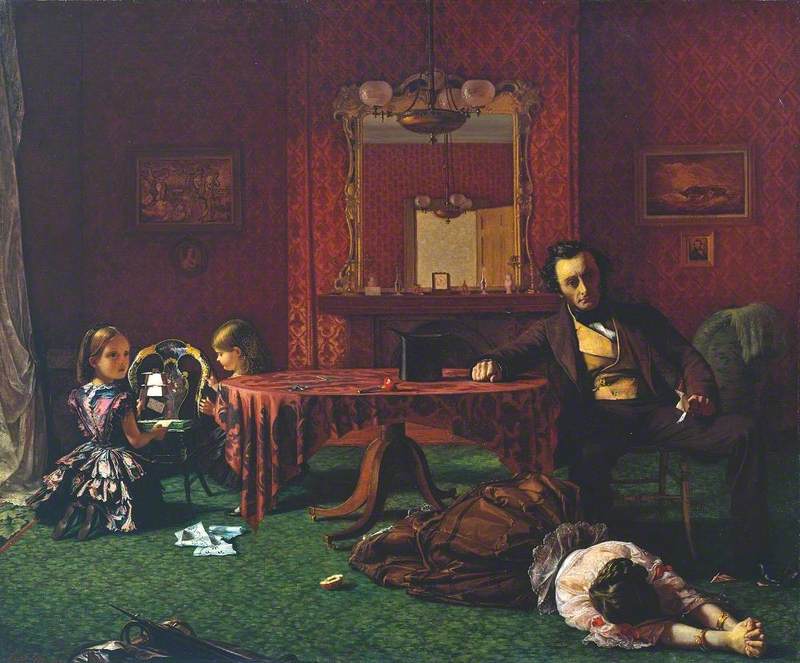

Lots of messages are present in this picture. The children are playing while their mother and grandmother are out of the house. The two children in the centre are pounding bread in a mortar and pestle to make tablets, but one child has taken the game a step further by climbing on a chair to open the medicine cupboard, and is pouring a measure of some dubious liquid into a glass to administer to the 'patient'. Fortunately, the adults are seen returning through the door, otherwise the patient might become like the doll in the bottom-right corner of the picture.

The long and successful career of Frederic Daniel Hardy (1827–1911) was principally devoted to painting happily nostalgic episodes in childhood, most often of a domestic and humorous nature. Children Playing at Doctors is a classic example of his work.

From play, we move to education.

Henriette Browne (1829–1901) was the pseudonym of Sophie de Bouteiller. She was a French Orientalist painter.

She was renowned internationally during her lifetime and specialised in genre scenes that represented the Near East in a less sensationalised, albeit still exotic, manner than her contemporaries. While many of her works have been lost, those that remain are a testament to the skill and sensibility of a painter largely overlooked by history.

This painting was also known as The Pet Goldfinch – perhaps hinting that education can lead to escaping a cage.

Like Playing with Doctors, A Girl Writing was part of a bequest of artwork by Joshua Dixon in 1886. Dixon was a merchant and art collector who bequeathed his collection to the Bethnal Green Museum. He gave 295 oil paintings, watercolour drawings, bronzes and statues specifically for 'the use of the public of East London'.

We now examine single portraits of children, from a variety of backgrounds.

This painting is by George Frederick Watts (1817–1904). Watts received no regular schooling on account of poor health, but later studied under the sculptor William Behnes and entered the RA schools in 1835.

He rose to front rank as a portrait painter and painted many of his eminent contemporaries including Thomas Carlyle, John Stuart Mill, William Gladstone and John Everett Millais.

Zoe Ionides (1877–1973) was the seventh of eight children of Constantine Alexander Ionides, the donor of the V&A's Ionides collection, and his wife Agathonike.

During a lifelong friendship, Watts painted over 50 members of the Ionides family spread over five generations. This portrait entered the V&A collection in 1920 after the death of Agathonike Ionides, along with 19 other family portraits.

Unlike the previous painting, there is no information as to who this boy was. The painter John Opie (1761–1807) was the son of a village carpenter. After many difficulties, he overcame his father's wishes and became a painter. He was self-taught and began to paint portraits at an early age.

When introduced to Opie, Sir Joshua Reynolds was very much impressed and crushed his former pupil James Northcote, who was then trying once again to establish himself in London: 'You have no chance here,' Northcote recalled Reynolds as saying to him. 'There is such a young man come out of Cornwall... Like Caravaggio, but finer.' Despite their rivalry, Northcote and Opie went on to be lifelong friends and Opie even painted Northcote's portrait.

Opie's portraits of children have been described as 'being better than those of almost any British artist of his time'. Although he was known in his lifetime his fame has faded. He was held in such high regard at his death that he was entombed in the same vault as Reynolds. But there was a mistake – the undertaker realised that the coffin was put in the wrong way round (with Opie's feet towards the west rather than the east). 'Shall we change it?' he asked. 'Oh, Lord, no!' replied Alderson, a cousin of Opie. 'Leave him alone! If I meet him in the next world walking about on his head, I shall know him.'

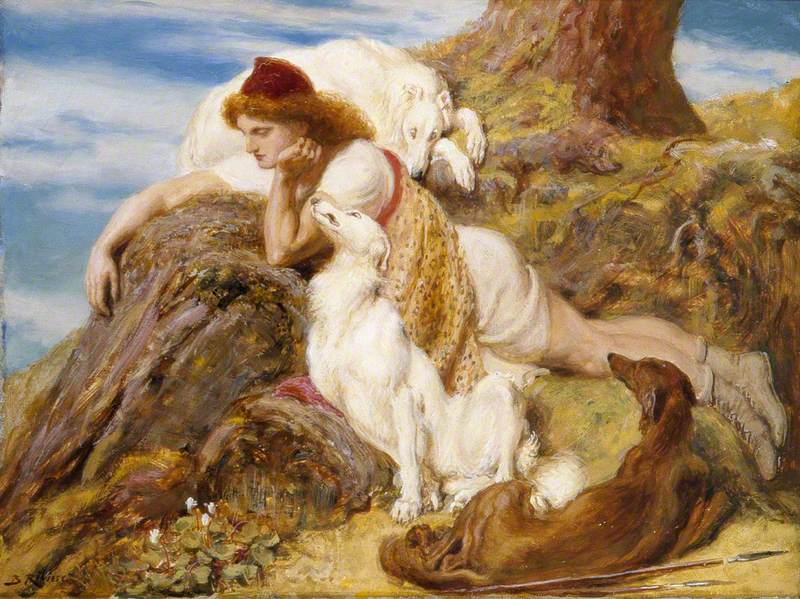

Here we have a work by Opie's friend and rival, James Northcote.

Northcote (1746–1831) was born in Plymouth, Devon, where he began teaching himself painting. In 1771 he moved to London to study at the Royal Academy Schools. He was a pupil and resident assistant to Sir Joshua Reynolds and exhibited over 200 works at the Royal Academy between 1773 and 1828.

Northcote also contributed to the literature on art by writing biographies of artists. He published the Life of Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1813 and The Life of Titian in 1830.

This portrait was acquired by the V&A in 1886 through the bequest of Madeleine Antoinette Godchaux and came into the museum named as Little Girl Nursing a Kitten. Through research, it was identified as being the portrait of the daughter of a Mrs Stately. This attribution has been made on the basis of the description in the artist's account book of the painting:

'Full length, standing young girl nursing a kitten in her arms, shaggy dog sits at l. (left) and looks up at cat.'

This is a painting full of restraint and expectation – any moment now the dog and the cat are going to run out of the painting! The cat certainly does not look comfortable with the current situation.

It is unusual in Britain in the eighteenth century to find a portrait of a baby by itself. Babies are more often shown as part of a family group. Single portraits exist of babies who had died, but they are usually shown in burial clothes. Here the emphasis is on the strong and healthy appearance of the child, who was perhaps the artist's own. A cheap model!

Portrait of an Unknown Woman and Child

1745–1750

Andrea Soldi (c.1703–1771) (possibly)

This portrait of an unknown woman and child in oil on canvas probably had a companion piece, as hinted by the child pointing out of the frame.

Andrea Soldi (c.1703–1771) was a Florentine painter who arrived in London in 1736. Soldi enjoyed considerable success with aristocratic patrons. His 'freely and well drawn' portraits were prized for their attractive light colour. Success apparently went to Soldi's head – in 1744 he was described as having a 'high mind and conceptions grandisses willing to be thought a Count or Marquiss, rather than an excellent Painter'. Soldi's popularity waned in the face of competition from a younger generation of British artists, including Sir Joshua Reynolds and at one time he was imprisoned for debt. Reynolds reputedly paid for his funeral.

My own favourite quote relating to the V&A Museum of Childhood and its collections is that by Henry Cole, when warned not to place a Majolica Fountain in the grounds of the Museum in 1872. This Fountain consisted of 369 separate parts and stood over 10 metres tall.

The Majolica Fountain in the International Exhibition

chromolithography on paper by Robert Dudley (1826–1909). Published 30th August 1862 in 'The Illustrated London News'

It was thought the 'rough' people of the East End would break it and steal pieces but Cole argued against this:

'When the idea of first establishing the museum at Bethnal Green was made known, it was stated that the valuables would be greatly damaged by the rough people who inhabit that part of the metropolis. I was cautioned not to put up a majolica fountain out of doors. The greatest local authority cautioned me, but I trusted the poor people, and I am glad to say that there has not been any damage done: on the contrary, that the people have shown great appreciation of the institution, and respect for it.'

Gary Haines, archivist and researcher at the V&A Museum of Childhood

As of April 2019, all of these paintings are currently on display in the V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green.