Scotland's rich cultural history weaves a complex narrative that includes the often overlooked story of the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) community. Despite having played an integral role in Scotland's art, music, stories and traditions, this is arguably its most marginalised ethnic minority.

When this community is viewed and portrayed through external lenses, for example in visual art, we can see how its narrative has been obscured and romanticised.

The GRT community in the UK encompasses diverse cultures and ethnicities, including English and Welsh Gypsies, European Roma, Irish and Scottish Travellers and other travelling groups. The term 'Gypsy' is accepted by English and Welsh Romani communities but deemed a slur by many European Roma communities. In this story, it is used to refer to artworks that have used the term, where appropriate.

In the twelfth century, Scottish laws referred to a group known as 'Tinklers', who were identified by their distinctive tinsmith craft. Regarded as a nomadic entity with unique customs and language, historical accounts suggest that this group enjoyed the freedom to pursue their activities under the protection of the King.

Later, in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Roma journeyed to Europe. This migration was triggered by the bubonic plague, for which they were wrongly blamed. It marked the beginning of a tumultuous journey.

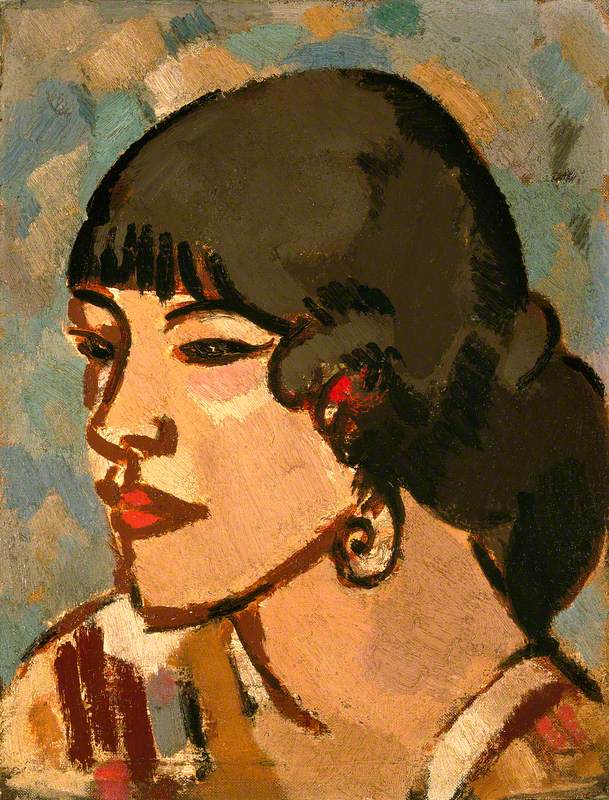

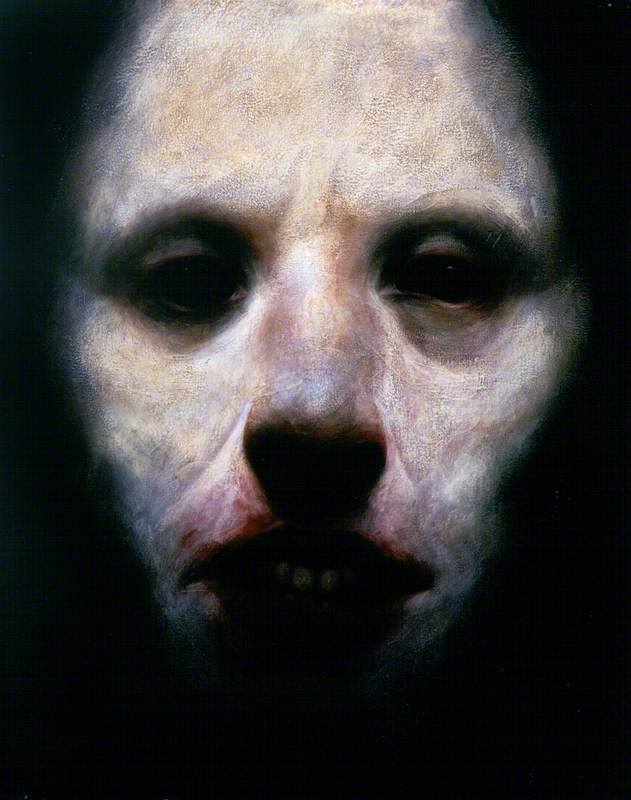

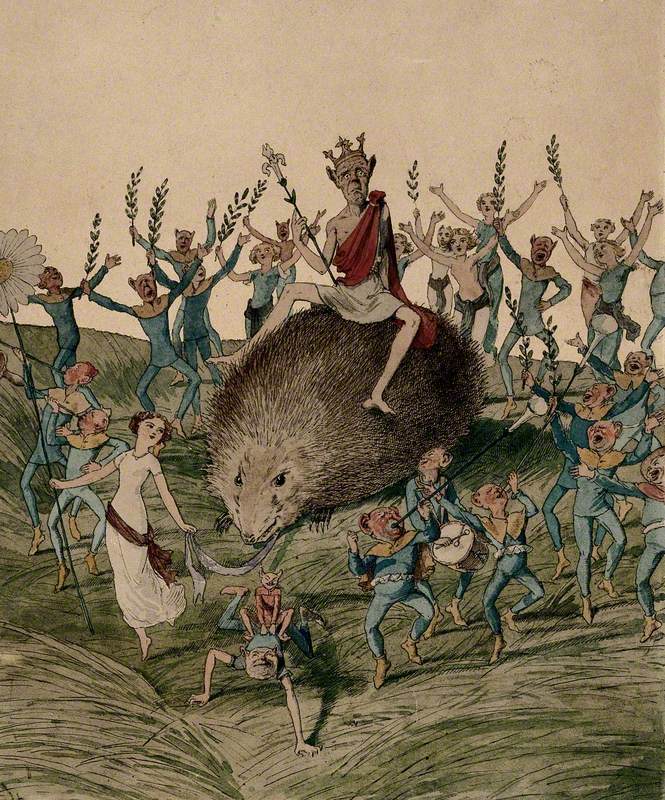

After the Roma's arrival in Western Europe during the Northern Renaissance, early artistic portrayals matched descriptions of them as 'dark-skinned' and 'horrid'. These depictions – associated with dirt, sin and evil – persisted for centuries. The church perpetuated the myth that the Roma's nomadic life was a punishment and linked them to Biblical characters such as Cain.

Themes of darkness and occultism were prevalent in many artistic depictions. During this period, terms for the Roma emerged: Zigeuner, Cingaro and Tzigan, from the Greek atsinganoi, meaning 'untouchable'. Gypsy, Gitano and Gitane derived from 'Egyptian,' as the Roma were thought to have come from 'Little Egypt'.

Arriving in Scotland in the fifteenth century, the Roma initially received a warm welcome under James IV, were granted safe passage and were paid for music and dance. However, accusations of criminal activity and greed soon shifted public perception.

The first law against 'Egyptians' in Scotland was enacted in 1541, and in 1579 punishments escalated to include hanging, branding and drowning. Portrayals of the community as sorcerers, witches and traitors to Christianity, persisted throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

In 1603, the Privy Council ordered 'Egyptians' to be expelled from Scotland under the threat of death, which resulted in numerous executions.

The last reported executions were in 1714, only 13 years before the final prosecution for witchcraft in Scotland. This illustrates the parallels that existed between Gypsy executions and witch trials – something that contributed to artistic depictions of Gypsy women with 'witch-like' characteristics.

Following the Jacobite defeat at Culloden in 1746, a significant chapter unfolded: the collapse of the clan system and the displacement of the Tinklers, who had been known for crafting objects for clans, such as armour and accessories.

A new nomadic group emerged, which, historical records indicate, came about as a result of integration and marriage between local nomadic craftsmen and immigrant Roma. During this period, many in this community adopted clan names such as McPhee, Stewart and McDonald. It was a blending of identities that culminated in the emergence of the group now known as GRT.

Forced into a nomadic lifestyle through displacement, they soon faced another obstacle, in the form of the Scottish Trespass Act of 1865, which criminalised encampment without the consent of the landowner.

This was followed by the Inquiry into Habitual Offenders, which advocated for containment, family separation and education as a means to erode the GRT culture.

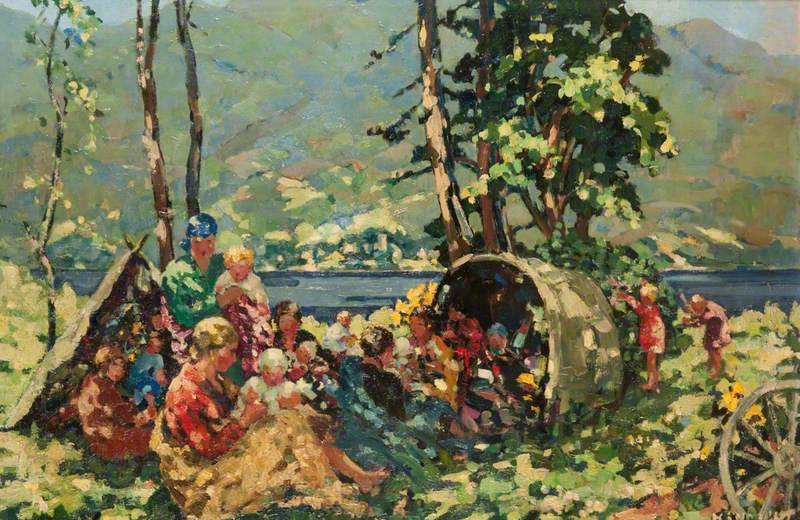

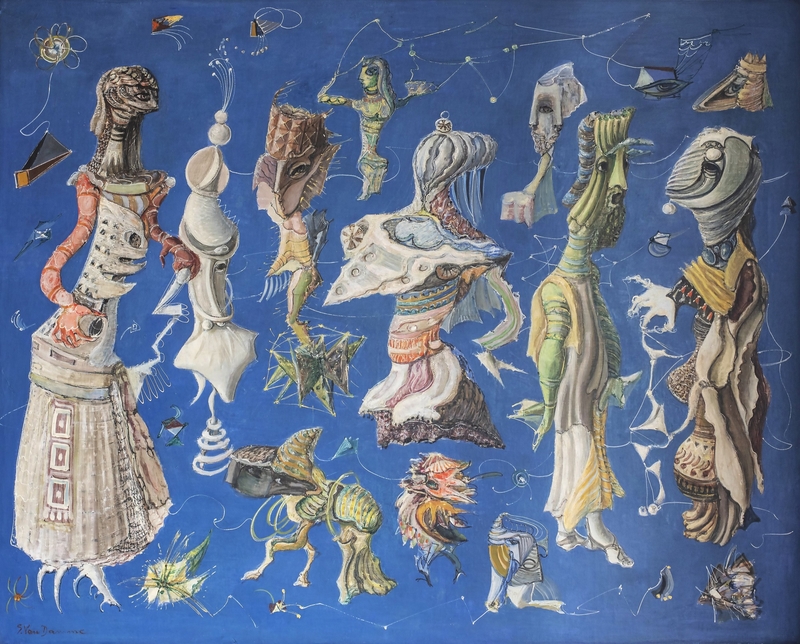

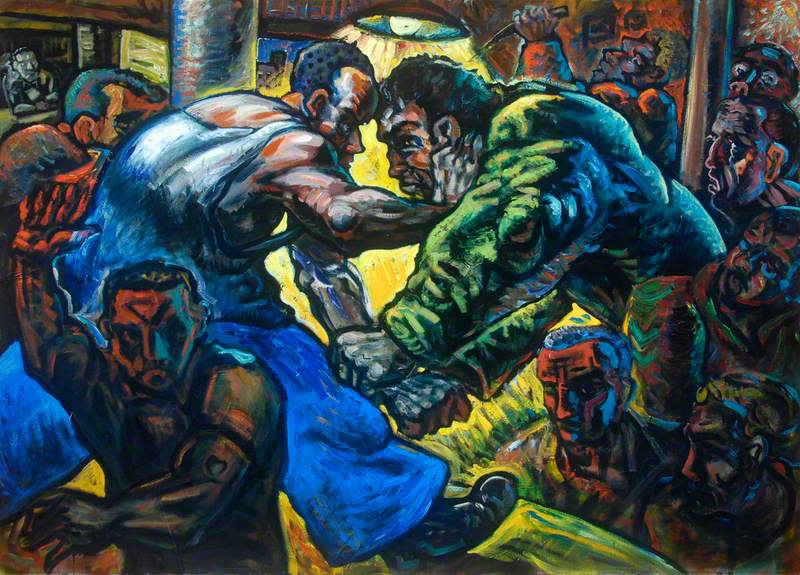

In the paradoxical nineteenth century, while legislation aimed to disable GRT culture, in art the lifestyle of 'Gypsies' became synonymous with the bohemian ideal, reflecting as it did a rejection of societal norms.

Originally a derogatory word used for French Roma, the term Gypsy evolved into something that epitomised momentary pleasures and artistic freedom.

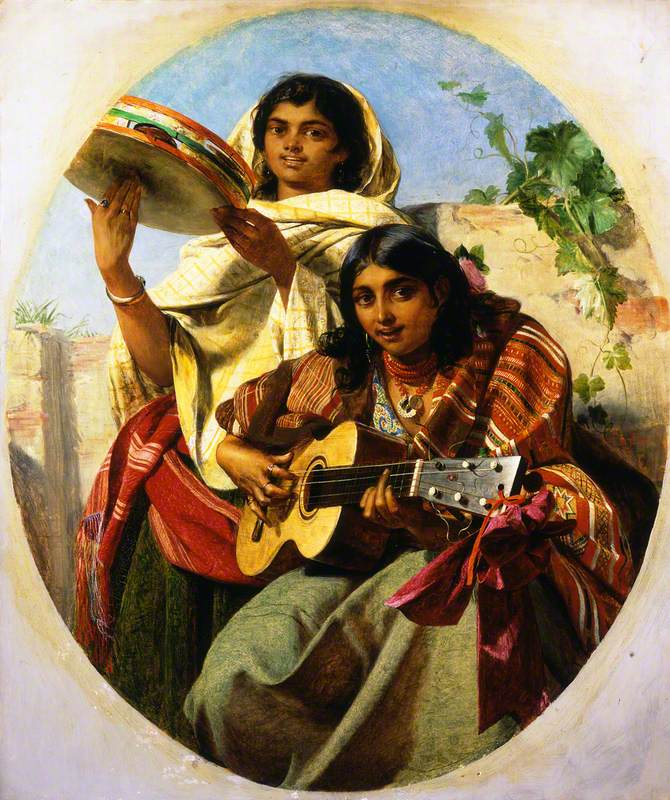

Gypsy Musicians of Spain (Spanish Minstrels)

1855

John Phillip (1817–1867)

The industrial transformation of the landscape heightened nostalgia for a pre-industrial world, with GRT symbolising an unspoiled, vanishing existence, often associated with poverty. The romanticised imagery created a fictional 'Gypsy-persona', raising stereotypes and feeding into distorted cultural perceptions.

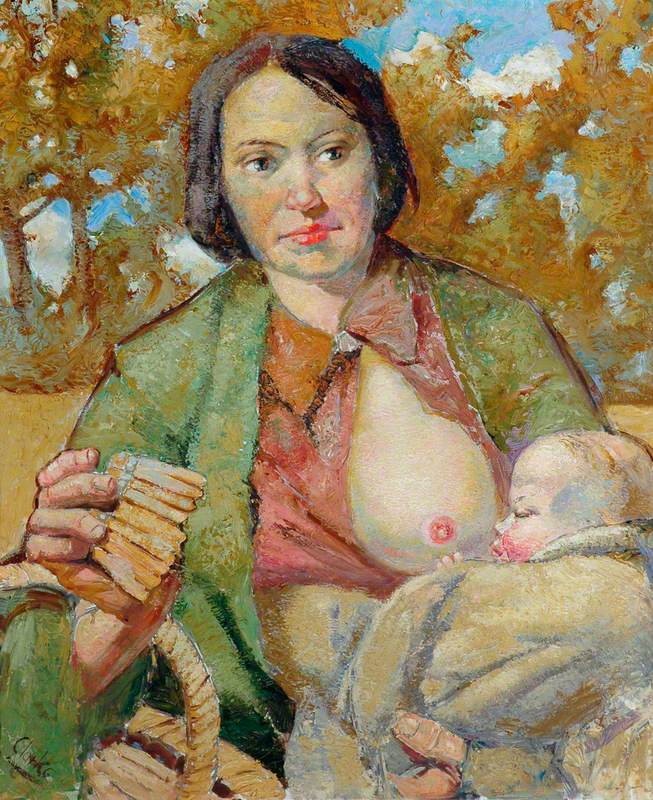

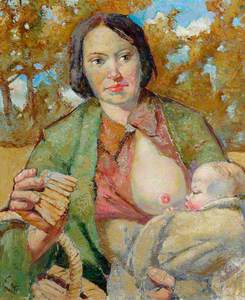

One typical depiction was the breastfeeding woman, symbolising a natural freedom in a public setting, contrasting mainstream society's strict social codes. Unlike the private photographs of Victorian mothers breastfeeding, paintings of nursing 'Gypsy-mothers' were destined for public display.

The artistic portrayal of GRT throughout history, shaped by external observations, has perpetuated prejudices among the wider general public. GRT are often defined in artworks by their way of life, emphasising biased observations rather than delving into the rich tapestry of their traditions and evolving identity shaped by various cultures.

Deep-seated prejudices, rooted in Westernised concepts of homeland, persistently cast them as outsiders, perpetual guests or unwelcome intruders. This perception mirrors their depiction in artworks as anti-social bystanders, often outside city walls.

The lack of heard GRT voices and information about the community solidifies their mysticised portrayal, contributing to the creation of an 'othered' identity.

The erroneous image of GRT as wanderers oversimplifies their diverse lifestyles, feeding into fetishising certain aspects of 'Gypsy-culture' and reducing their complex heritage to stereotypes.

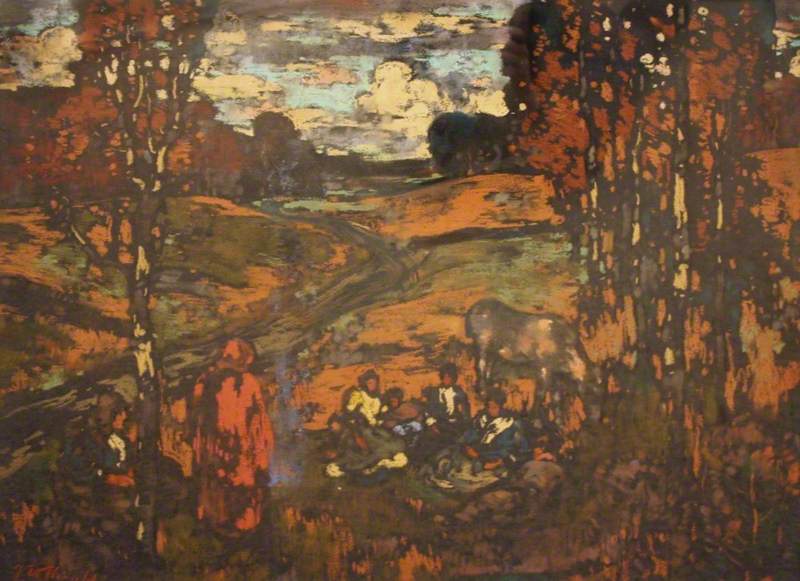

In visual art, members of the GRT community are often melded into landscapes, erasing individuality as they fade into shadows and darkness – a visual othering relegating them to societal fringes.

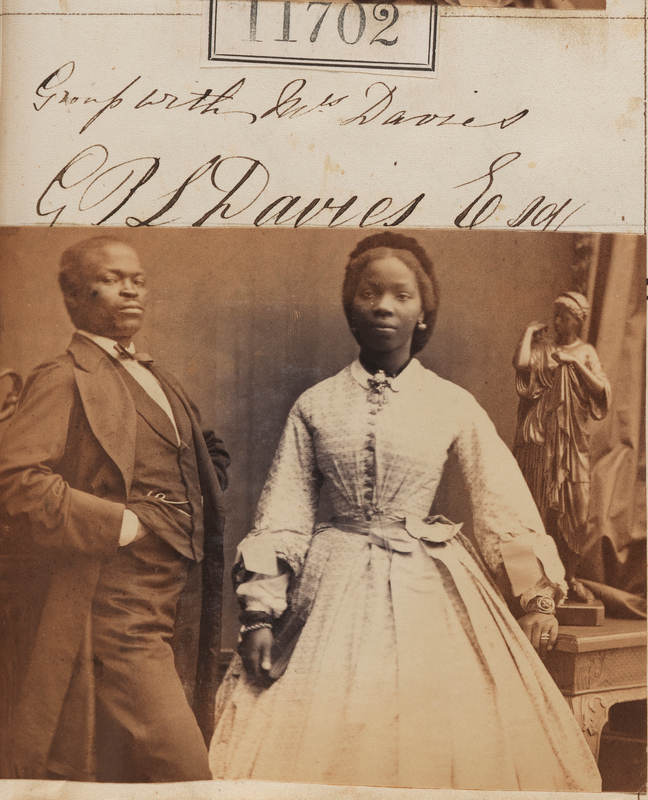

The outsider's gaze neglects their recognition as individuals with distinct personalities, reducing them to generalised 'Gypsy-concepts' without names or identities.

The widespread use of 'Gypsy' in artwork titles emphasises an image of a distinct way of life rather than acknowledging a multi-faceted identity, perpetuating one-dimensional narratives and fortifying societal misconceptions about the rich GRT community.

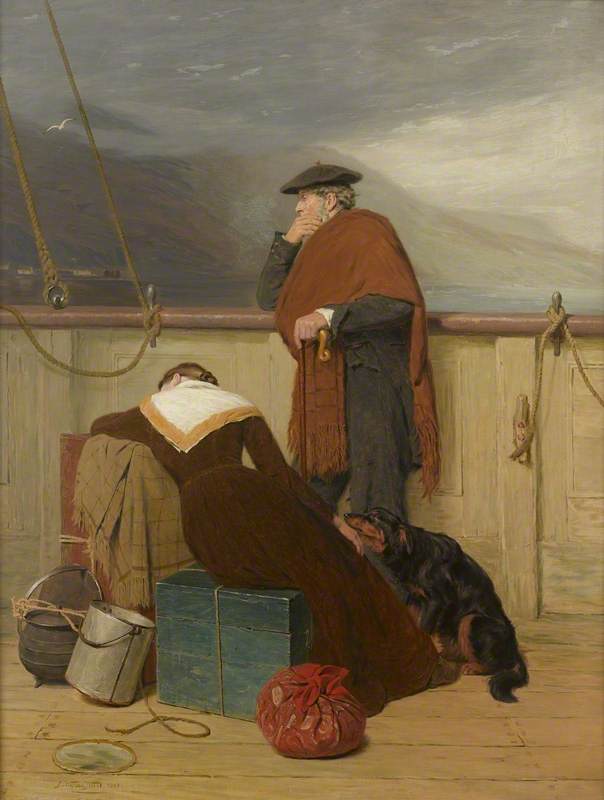

The Gypsy Fires Are Burning for Daylight's Past and Gone

1881

James Guthrie (1859–1930)

Recognising this complex history is vital for understanding GRT representation in art and dismantling enduring prejudices.

Artistic depictions, originating from external perspectives, reinforce fictionalised narratives and biases. These works can portray GRT as nomads with 'barbaric' lifestyles, underpinning prejudiced notions of criminality, the supernatural and a romanticised 'Gypsy dream' of liberty.

Fictional Gypsies in literature and art systematically erase real GRT history, replacing it with myth. This erasure assaults cultural identity, diminishing the role of memory in shaping the community's sense of self.

It allows outsiders to project fantasies and anxieties onto the GRT population, using them to explore anti-social urges or subconscious fascinations – the 'Gypsy' as a symbol of freedom was born in the nineteenth century, detached from societal constraints, fostering both fascination and resentment.

Constant misrepresentation and marginalisation impose a significant emotional burden on the GRT community, leading to heightened tension, a sense of duality and a continuous need for explanations and defence.

The lack of a written history for the GRT community contributes to their vulnerability, as written histories define identity, especially in Western European thinking. The obscurity of GRT history challenges conformity to established standards, rendering them unheard and unseen.

Art serves as a timestamp and evidence of societal perceptions throughout history. Whether accurate or prejudiced, information from art is invaluable, acknowledging that while art perpetuates stereotypes, it also has the power to transcend them.

Gamesters with a Gypsy Fortune Teller

c.1620

Bartolomeo Manfredi (c.1582–1622) (style of)

The historical context in artworks sheds light on society's thoughts about the GRT community, providing insights into the roots of misinformation. This enables a dialogue, the establishment of counternarratives, challenges to misconceptions and the fostering of GRT agency.

Instead of dismissing artworks because of misconceptions, we can use art and culture to engage in this dialogue. This inclusive approach allows untold stories to be heard, enabling the GRT community to embrace their own culture and identity.

Aila Schafer, historian and researcher

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

Further reading

Ian Hancock, We are the Romani People – Ame sam e Rromane dz̆ene, University of Hertfordshire Press, 2002

Donald Kenrick and Colin Clark, Moving on: The Gypsies and Travellers of Britain, University of Hertfordshire Press, 1999

David Macritchie, Scottish Gypsies Under the Stewarts, D. Douglas, 1894

Andrew McCormick, The Tinkler-Gypsies, J. Maxwell & Son, 1907

Judith Okely, Own or Other Culture, Routledge, 1996