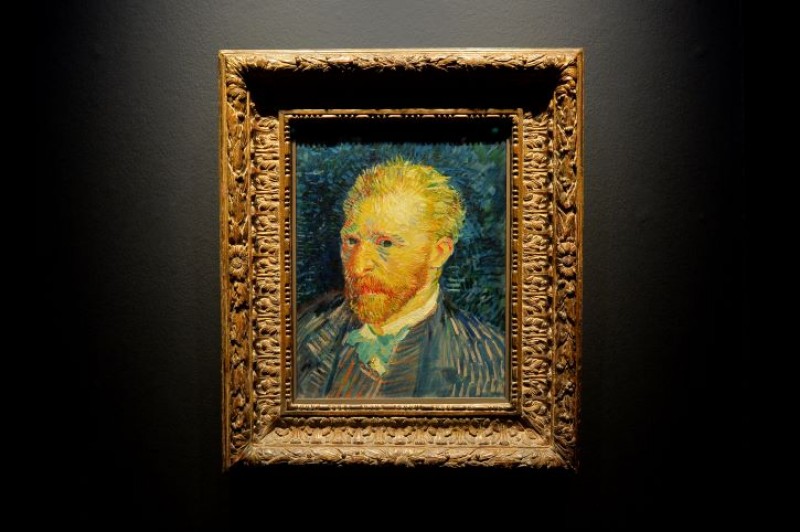

Art UK offers a superb array of painted self portraits, especially by British artists. The first English self portraits date from the middle ages, but the vogue for self portraiture in Britain properly starts with King Charles I, one of the very greatest collectors and patrons. He endorsed the Italian renaissance cult of art and artists and owned self portraits by Dürer, Titian and Rembrandt (probably the youthful picture in Liverpool), and examples by his court painters Mytens, Rubens and Van Dyck hung in his breakfast room.

Van Dyck was a prolific painter of self portraits, usually looking dashingly over his shoulder – an artistic aristocrat – and he became the catalyst for an upsurge in the production of glamorous self portraits (with not a paint brush in sight) by British artists for the rest of the century.

Robert Walker, despite being the foremost portrait painter to the parliamentary side during the Civil War, shows himself as the swaggering keeper of Van Dyck's flame, and points to a statue of Mercury, a symbol of the arts included in an engraved Van Dyck self portrait. Mary Beale, the first professional woman painter in Britain and a prolific self portraitist, paints herself c.1680 as a carefree Van Dyckian shepherdess with her young son as a Cupid-like shepherd boy.

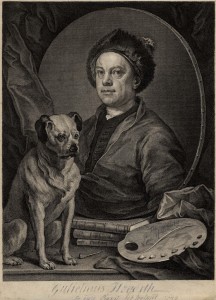

Hogarth's sardonic self portrait with his pug dog, his oval picture within a picture propped up on volumes of Shakespeare, Milton and Swift, is a bold refutation of the 'foreign' Van Dyckian tradition.

Its conceptual and intellectual ambition perhaps implies the frivolity of the Van Dyckian world view. On the face of it, Hogarth's aesthetic rebellion may appear to have failed. Sir Joshua Reynolds, first president of the Royal Academy, still shows himself in Van Dyckian mode in his great 'hand-on-hip' self portrait – despite the presence of a sombre portrait bust of Michelangelo.

And yet Reynolds' Self-Portrait as a Deaf Man (c.1775), cupping his hand on his ear, has a Hogarthian wit, humanity and sobriety.

A good portrait was traditionally called a 'speaking likeness', insofar as you felt you could hold a conversation with it, but here Reynolds' deafness is impeding the discussion. This may well be the first self portrait to allude to a disability, but it also implies Reynolds is his own man and will not listen to criticism or follow fashion.

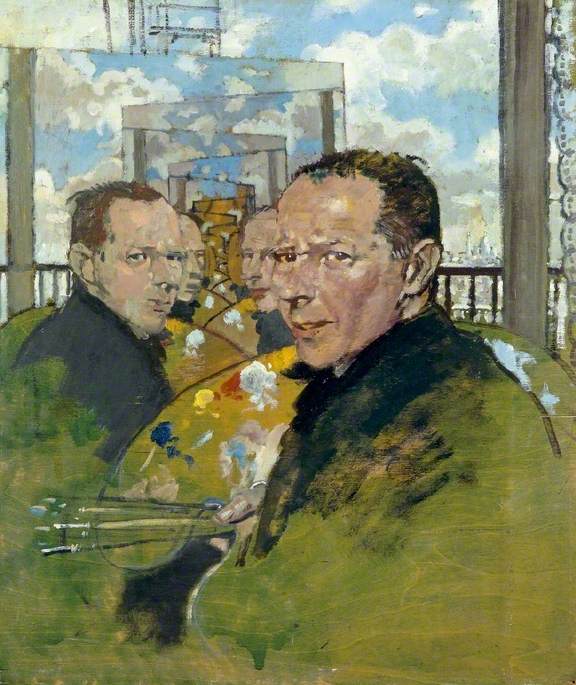

Whereas in earlier centuries, British artists were keen to allude to their artistic forebears, in the twentieth century they are increasingly likely to demonstrate their autonomy. The remarkable self portrait by society portrait painter William Orpen from the 1920s shows him seemingly sitting in between mirrors, neither indoors nor outdoors, his reflection (and a cloudy sky) multiplied ad infinitum into the distance.

It could almost be an illustration of a criticism of the narcissism of modern artists made by the German philosopher Nietzsche – 'with fifty mirrors around you, flattering and repeating your opalescence!' But there's also something melancholy about Orpen's blotchy, incomplete image: reduplication is also disintegration.

James Hall, author of The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History, published by Thames and Hudson