London-based Polish artist Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński merges sculpture and painting in a distinctive style that transforms materials into textured, thought-provoking works. His art reflects both a deep respect for classical forms and a commitment to addressing contemporary issues, particularly the physical, social, and emotional barriers that divide us.

Educated at the Fine Art Academy in Krakow and London's Slade School of Art, Sobczyński has built a career spanning over 80 group exhibitions and numerous solo shows, including a decade-long collaboration with Julian Hartnoll Gallery. His work has been showcased internationally, from the Centre for Contemporary Arts in Toruń to London's POSK Gallery.

Born amidst conflict in Eastern Poland and shaped by the challenges of migration, Sobczyński's personal journey informs his ongoing series of works. Drawing from his own experiences and the unfolding global tensions, his work creates powerful visual narratives that spark essential dialogue.

Beyond his art, Sobczyński is an active cultural advocate, contributing critiques to esteemed publications and fostering creative exchange through initiatives like the 'Polish Connection'. His art, rooted in resilience and creativity, invites us to reflect on humanity's struggles and shared aspirations for unity and peace.

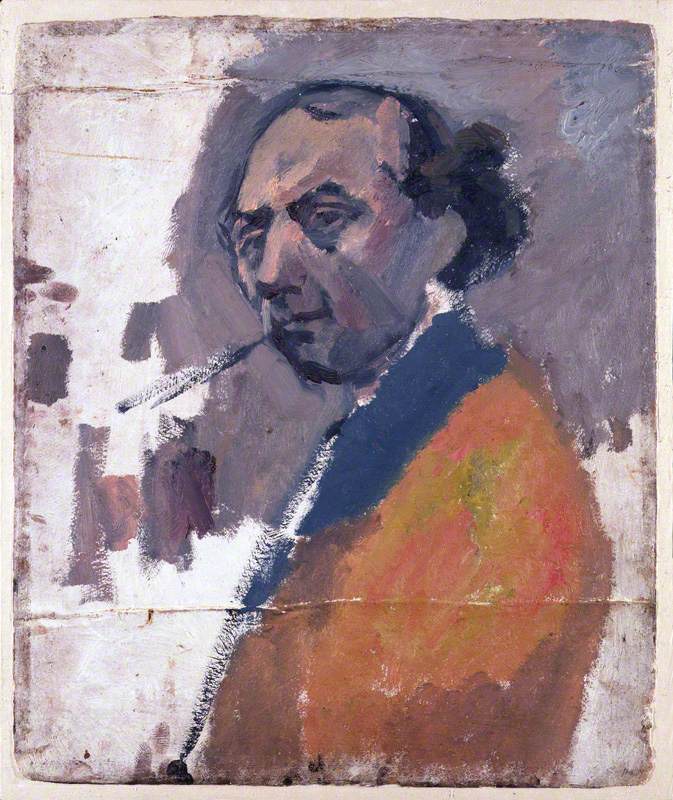

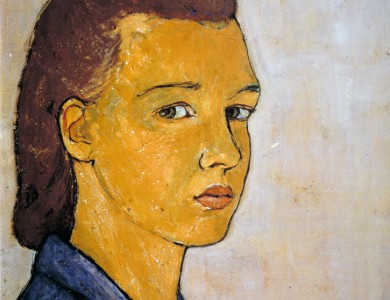

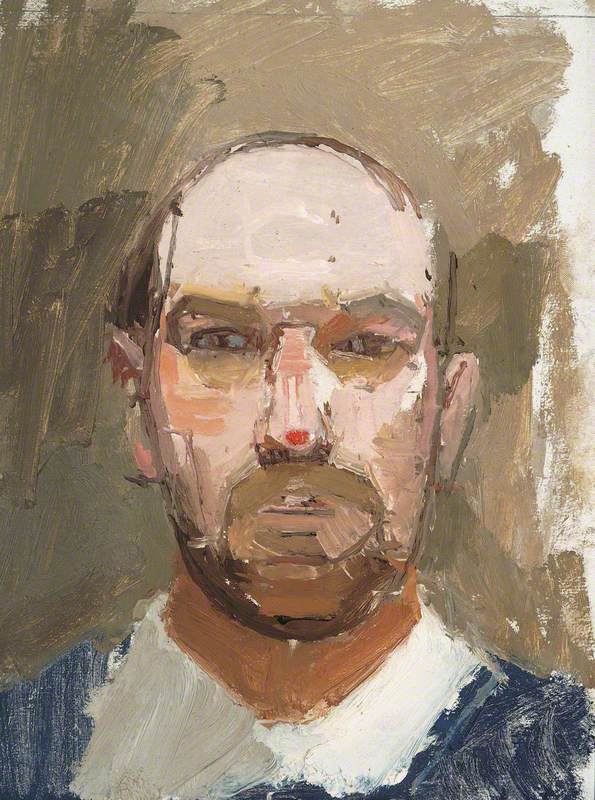

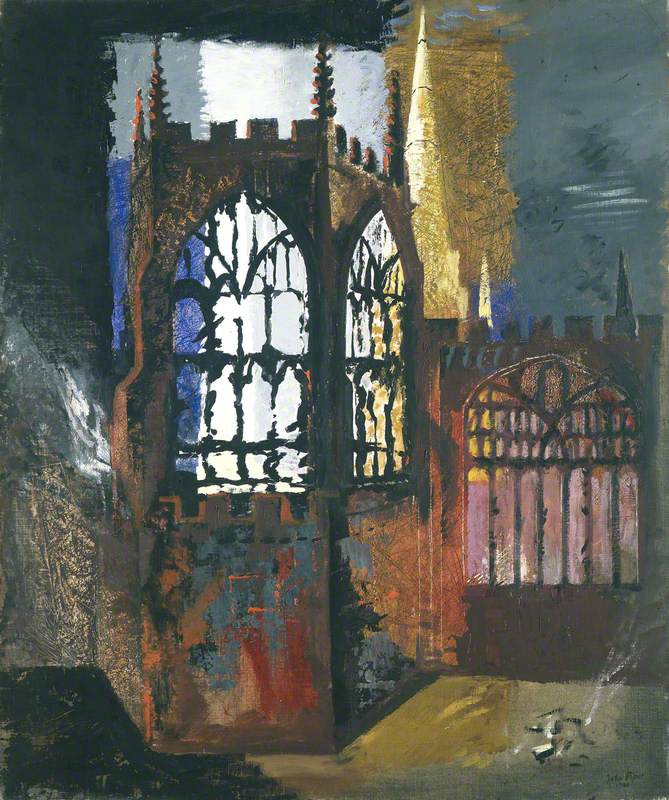

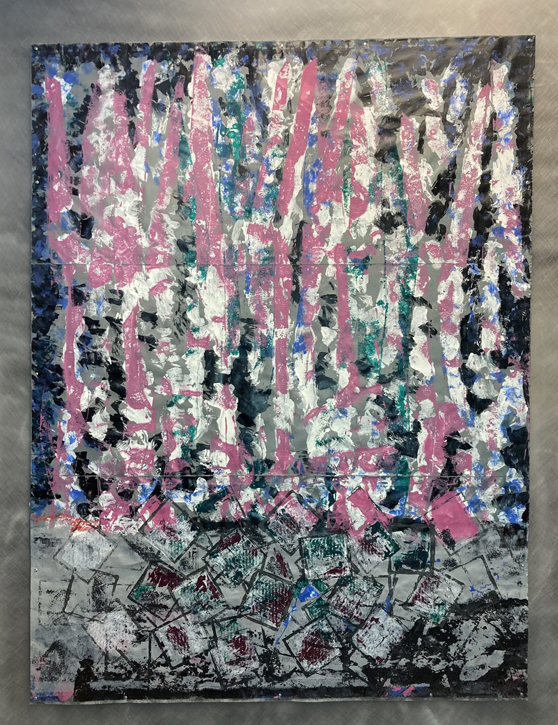

Untitled

2024, painting by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

To coincide with his solo exhibition 'Barriers & Borders' at Morley Gallery, Melissa Baksh caught up with the artist to find out more about his life and work.

Melissa Baksh: When did art become a meaningful part of your life?

Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński: That started at an early age, because I had the wonderful opportunity to study my grandfather's encyclopaedic art history books, which were full of both classical and prehistoric art. My grandmother studied art in Kyiv's art school. I remember early photographs of my grandfather and grandmother standing in a room with two easels, both of them painting. My mother was also always making things, but out of necessity – knitting jumpers, socks and gloves.

Melissa: How about your early interactions with sculpture?

Wojciech: After looking at my grandfather's art books, it seemed obvious that the three-dimensional shapes were of interest. I made my first carvings by lumping big chunks of mixed plaster to make a kind of rock, and then carved in it, producing fairly primitive shapes. My mother, who worked in cafés, would collect the lead content of white wine bottle tops for me, and I would smelt them down and make my first lead casts of these sculptures.

Sculptures by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

From the exhibition 'Barriers and Borders' at Morley Gallery

Melissa: Your work addresses themes of global conflict and violence. How has conflict impacted your life?

Wojciech: My mother lived through a very difficult period because she got married, quite literally, on the declaration of war. My parents got hitched and then my father went to the front. Nine months later, my older brother was born.

Towards the end of the war, on Liberation Day, German troops arrived and my mother – with labour pains and in the final stages of pregnancy – was ordered to leave the house. She escaped to the woods, and that is where I was born. When we returned, Russian troopers were there, helping themselves to whatever was in the house, which was windowless but standing. 'Liberation' was a new kind of reality, but it was still harsh.

Melissa: Can you tell me about your love of music, specifically jazz?

Wojciech: Right from the beginning in Krakow, jazz music was non-conformist music. It was what youngsters would listen to. It was coming from all directions, but principally, the best stuff was from America. At this time, jazz spread quickly all over the world. Musicians from East and West were playing together, sometimes even improvising together.

When I was a student, I ran a club in the basement of the Fine Art Academy and encountered jazz music from all over the world. Against the backdrop of an authoritarian system in Eastern Europe, this was scintillating.

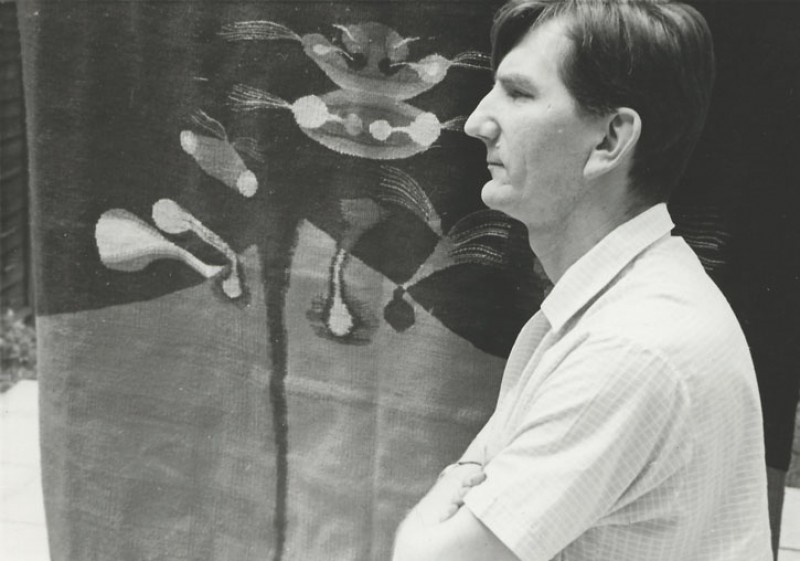

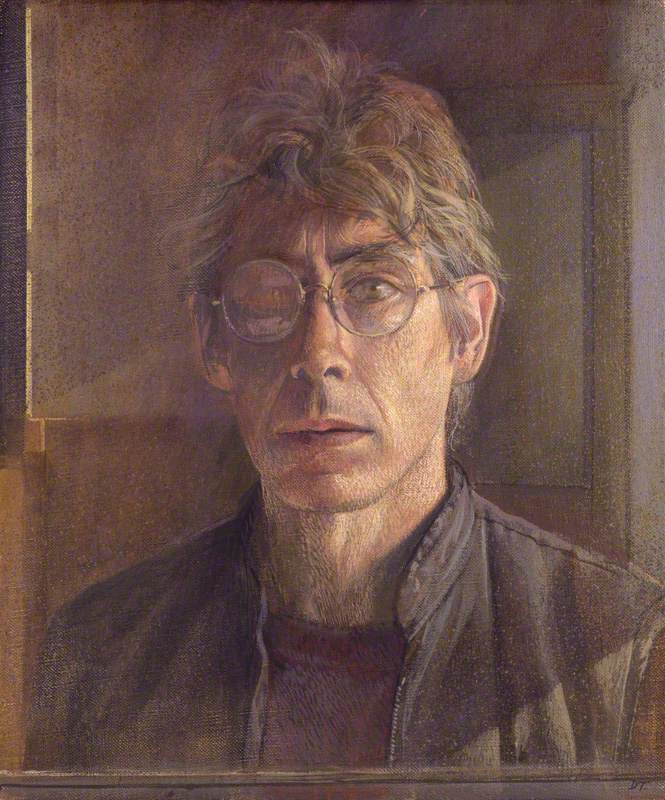

The exhibition 'Barriers and Borders' at Morley Gallery

Works by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

Melissa: How did you come to move to England?

Wojciech: I had my Diploma Show at the Academy in Krakow during the time in which the Courtauld Institute of Art's Summer School students were visiting. Whilst in a café, I was introduced to the students, and invited them to my Diploma Show which was about 100 meters away. They visited and liked my work.

Two days later, Barbara Robertson, a private benefactor who ran the Summer School sent me a message to tell me that I got a scholarship to study in England. So it really happened like a dream of coincidence. Sometimes you think nothing of it, but the consequences in my life have been quite profound.

Melissa: How did moving to London affect your practice?

Wojciech: When I came to England, influences were hitting me from left, right and centre. One of these influences was colour. I came to see colour in a completely different way. British society of the Flower Power period was very colourful, as opposed to grey and drab Eastern Europe. When I came here, I was completely bowled over by what I was seeing, not only on the street, but in the art galleries.

The exhibition 'Barriers and Borders' at Morley Gallery

Works by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

Melissa: How has your sculptural practice evolved over the years?

Wojciech: Sculpture is always in the back of my mind. I respond to sculpture. I look at sculpture. If there is sculpture to be seen, I have to stop and check it out. Romanian sculptor and painter Constantin Brâncuși is a pet love; I always admired the simplicity of his sculpture. But I always try to step out from convention, and so I stepped out from a strictly three-dimensional approach. I wanted to blend it with the two-dimensional to give it a painterly quality. So my output at the moment is a bit of painting and a bit of sculpture.

Melissa: Please could you tell me about your exhibition at Morley Gallery, entitled 'Barriers & Borders'?

Wojciech: When I started preparing the work for the exhibition, the terrible news of the Russia-Ukraine war came about. The reports of hundreds of tanks going from Belarus towards Kyiv upset me very much. I thought about this country that had been clamouring for freedom for centuries, and every time it was close to freedom, there was some intervention which was stopping it.

For me, globalisation is about living with open borders and an exchange of ideas. I really thought that, as a global society, we could finally reject force as a method of sorting out problems. For me, war is the ultimate barrier. When I think of conflicts, I remember Goya's The Horrors of War, Picasso's Guernica and David Smith's Medals for Dishonour series. I would like my pictorial 'Barriers' and barricades to offer up a discourse of peace and common humanity.

Melissa: Can you tell me about some of the works in the exhibition?

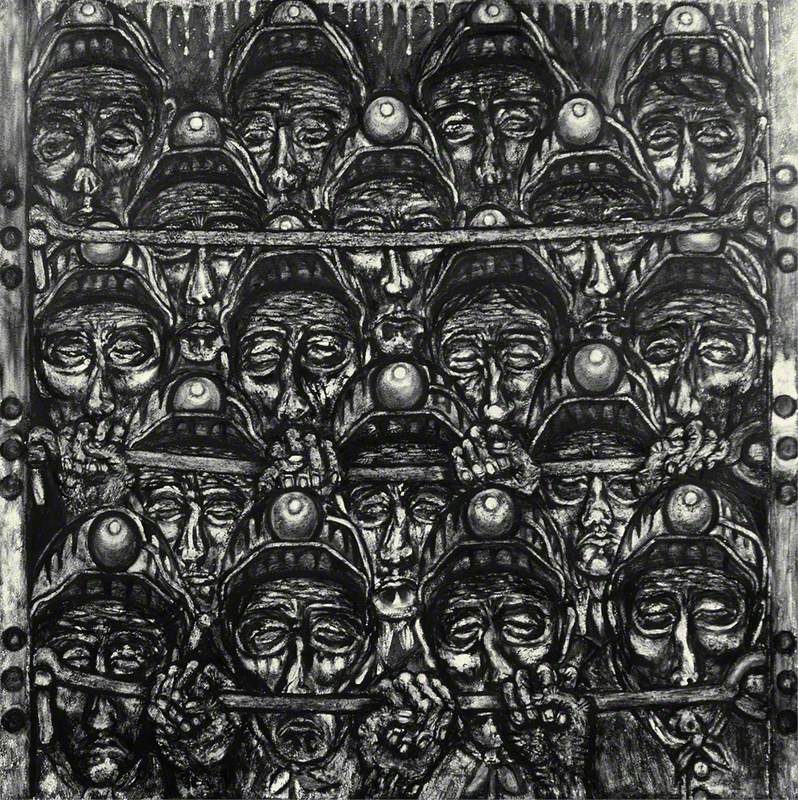

Wojciech: For WMMWM, the exhibition's title image, I had this kind of multiplier of shapes in my mind from early on.

WMMWM

2024, painting by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

Because it's Morley, and it's because it's Wojciech, I played with the inverted M, which looked remarkably like my initial. There is this contrast between the exploding upper part and the much more static lower part. It is like a painting: the lower part with cooler colours and warmer colours above, which is my method of constructing the image as a sort of residue notion of a landscape.

Stones Are Mute was first constructed to be a painting, but I frequently want painting to have the possibility to be away from the wall, so it is free-standing as well.

Stones Are Mute

2024, mixed media by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

When the conflict in the Middle East happened, there were many photographs of calamities emerging. The debris and lumps are suggestive of what we have been witnessing through our screens – of communities exploded into smithereens. I completed Blind Face of Violence within two weeks of the Russian attack on Ukraine, just before the exhibition opened. I wanted to create a piece that would have an immediate expression of fright.

Blind Face of Violence

2022, mixed media by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

There is a large piece called Counterpoint, which is a musical term, because there are various shapes in the incline, in right angle positions. They remind me of a keyboard, of the piano and the horizontal lines on which these keyboard pieces are mounted are almost like the note paper for a musical score.

Counterpoint

2024, mixed media by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

Alongside this is the Bagatelles series. 'Bagatelle' is a French term, but it is also used in Polish. It is indicative of a light-hearted, mellow piece of music. The works are not pretending to have some great dramatic expression; it's conceived with this lightness of intention and concentrates on the elements which I've included in it – in this case, colourful, chromatic exercise of variations.

Bagatelle Series

Paintings by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

One of my more joyful pieces is After the Rave. It's a crowd observed in North London: a group of youngsters, colourfully dressed, getting up to whatever they want to get up to.

After the Rave

Painting by Wojciech Antoni Sobczyński

There is a density of vertical persons standing, bopping, the rhapsody of colours echoing and vibrating, reminding me of my early days in London.

Melissa: You're very local to Morley Gallery and you've been a Londoner for many years. What about London inspires you?

Wojciech: London has been a constant source of visual nourishment over the years. One only has to look up in different directions, and you can discover many treasures. Eduardo Paolozzi's sculpture of Newton in the courtyard of the British Library is one example.

I am very lucky that I have mostly operated in central London. The sprawl of suburbia has its charm, but it can't compete with the view from Waterloo Bridge. You are immediately immersed in culture. On one hand, you've got the National Theatre, where you have great plays, and you've got the Tate and Hayward Gallery, where you've got great art. It's a joy to be on the river and admire this.

Melissa Baksh, art historian, freelance writer, and Gallery and Exhibitions Officer at Morley College London

Wojciech has generously donated one of the exhibited works, an untitled acrylic painting, to the Morley College Art Collection, a significant and growing body of contemporary works acquired and displayed to support Morley College London's renowned visual arts teaching programme

The exhibition 'Barriers & Borders' is at the Morley Gallery from 15th to 30th January 2025