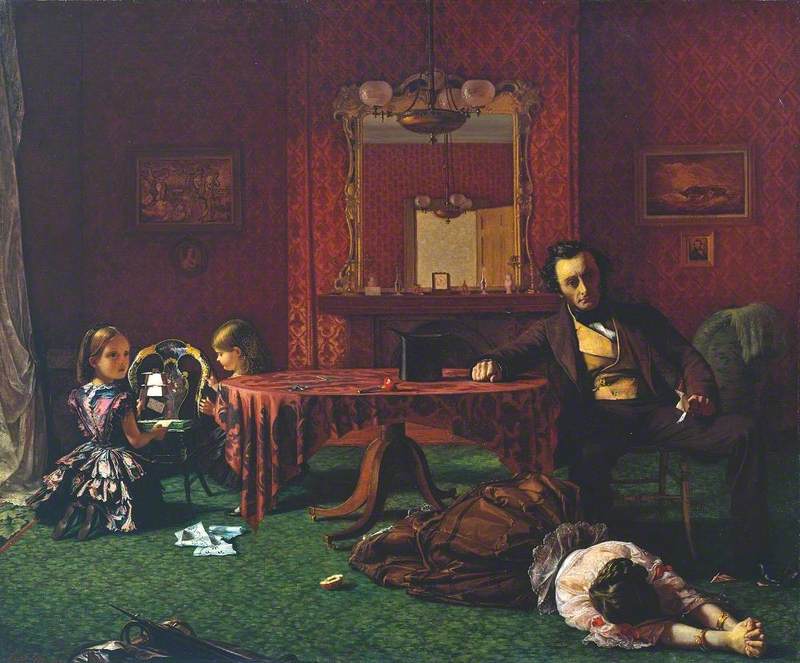

Chastely submitting to your husband, performing household duties diligently and providing comfort for your children – this was the primary purpose of the Victorian woman. The wife in Augustus Leopold Egg’s Past and Present (1858) has clearly fallen short.

The scene is set in their opulent house where the husband has just learnt of his wife’s affair. He clutches the letter from her lover that he intercepted and his dark stare towards us pulls us into this uncomfortable private encounter. She is collapsed on the floor desperately pleading with him, her bracelets reminiscent of handcuffs. Their daughters half play and half look on from the corner. The house of cards they are building, a perfect metaphor for their family, falters on the verge of crumbling.

The story continues in the second part of the triptych, set five years later, where we see the daughters in a sparsely decorated room. They have been orphaned after the death of their father and cling to each other for comfort. In the final painting, the destitute mother crouches alone in a dark arch. She is an outcast, the affair is now clearly a thing of the past and she holds onto the result of her transgression, another fatherless child.

Egg executed every aspect of the triptych with such clarity and individuality to leave no doubt in our minds that the wife sinfully deviated from her motherly duties, loyalty to her husband and society’s expectations. She encapsulates a regular subject in Victorian art – the woman who has failed.

Despite Queen Victoria being a pioneering, powerful and visible ruler of one of the world’s most influential countries, it was her early marriage to Prince Albert, unwavering loyalty to him and large family that influenced the standards to which women were expected to aspire. Queen Victoria somehow became the epitome of the ideal domesticated Victorian woman.

Women were subsequently portrayed in art as ‘ministering angels’ as in Charles West Cope’s The Young Mother (1845). In George Elgar Hicks’ Woman’s Mission: Companion of Manhood (1863) which was painted five years after Past and Present, the central panel of a triptych shows the perfect wife who is great at running her home. She is suitably dressed, fresh flowers are on the mantelpiece and breakfast is neatly set on the table. Upon her husband hearing the news of the death of someone close to him, she leans in, focuses on him and remains by his side.

Women today are still expected to be the doting nurturer and companion and those who depart from this gender script for whatever reason are judged harshly for doing so. Ariana Grande was forced to speak out earlier this year after was she criticised for leaving her toxic relationship with ex-boyfriend Mac Miller, who had struggled with substance abuse throughout his life, because he had ‘poured his heart out on a ten song album to her’. In the wake of his recent fatal overdose, trolls called Grande selfish for not doing more to help Miller's addiction and mental health and insinuated she was responsible for his death. #ArianaKilledMac became a trending hashtag.

In a headline that has now rightly been changed by the Mirror, the newspaper asked what would happen to presenter Holly Willoughby's children while she was presenting 'I’m A Celebrity...' in Australia. Its accusatory tone implied that Holly, who lives with her husband and father of their children, is their sole carer and is abandoning her maternal duties by taking on a new role.

Image credit: image capture sourced from Twitter

The same questioning has not been applied to her male co-presenter Declan Donnelly who will be leaving his new-born baby behind, revealing a double standard. Similarly, the wellbeing of the three children in Past and Present is portrayed as being the responsibility of the wife and not of their fathers. It was widely permissible in Victorian society for ‘a man to indulge his sexual appetites illegitimately, either before or after the marriage vow’. For a woman to do so was unspeakable and the demise of a family was easily blamed on the wife.

With so much pressure put upon Victorian women to be sacrificial, generous, submissive, soothing and nothing short of perfect, some inevitably failed. The woman in Past and Present No. 1 is so full of shame that she is completely deflated. Shame is that intense feeling that says there is something deeply wrong and even repulsive about yourself. It arises from being part of a species that desires to be loved, seen and known by others.

We know where we stand within a community by the images reflected back to us, and have created social structures where certain people and attributes have more value than others. The images of the ideal Victorian or modern woman we see are often constructed through a male lens that both men and women have internalised. When Madonna, who has had more singles in the top five than any other artist, turned 60 this summer, there was a debate on national TV on whether she ‘should start acting her age’ instead of a discussion about all her groundbreaking achievements.

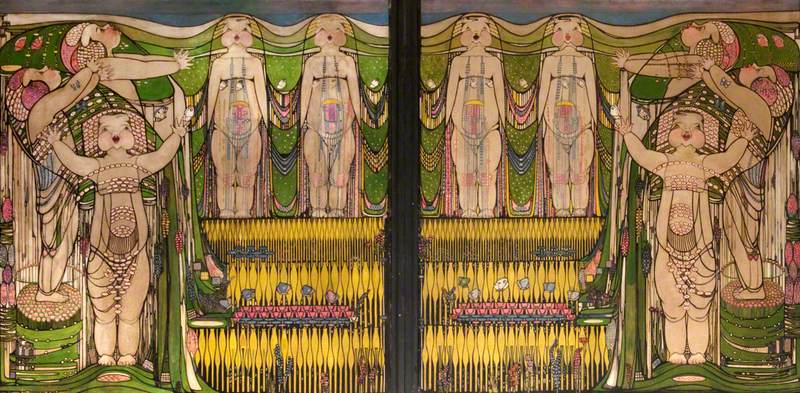

© the artist. Image credit: The Fairground Heritage Trust

John Walter Shaw's 'Easyrider': Madonna (centre shutter, recto) 1990–1995

Paul Wright (b.1954)

The Fairground Heritage TrustWhen Serena Williams showed frustration at having points docked and put at a heavy disadvantage at the tense US Open final, she was ridiculed as being angry, childish, petty and even beastly. In the wake of the furore, the Australian newspaper Herald Sun published a controversial cartoon to emphasise how far she falls from decorum and the model athlete.

The cartoonist Mark Knight (who has now deleted his Twitter account) relied on racist stereotypes to depict Serena with coily hair, exaggerated lips and oversized breasts and bum. She is seen in the middle of a hissy fit stomping on her racket which lies next to the dummy she has just spat out. Further back, a petite blonde figure – who is meant to be Haitian-Japanese Naomi Osaka – attentively listens to Portuguese umpire Carlos Ramos. They are having a level-headed discussion to find a solution to Serena’s temper tantrum.

Knight’s conscious decision to completely ignore both their ethnic heritages and depict Osaka and Ramos as essentially white attaches rationality, manners and good sportsmanship solely to white people. Serena Williams, a black woman who is evidently comfortable in her own skin, can therefore never measure up.

There has always been an impossible rulebook for women to follow. Visual culture and now the media have played great roles in policing our behaviour. When women are deemed to have strayed from someone else’s version of perfect, they are publicly shamed to put them back in their place, so to speak. The result is that as women, we either suffer the damaging weight of criticism or try to hide and diminish ourselves. This only ever limits our potential.

Chiedza Mhondoro

.jpg)