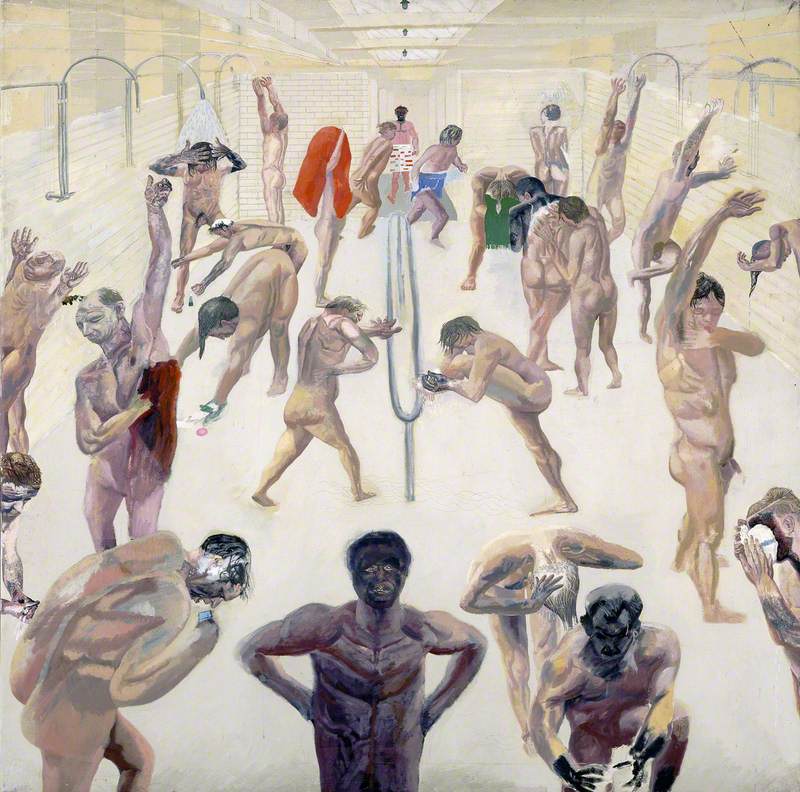

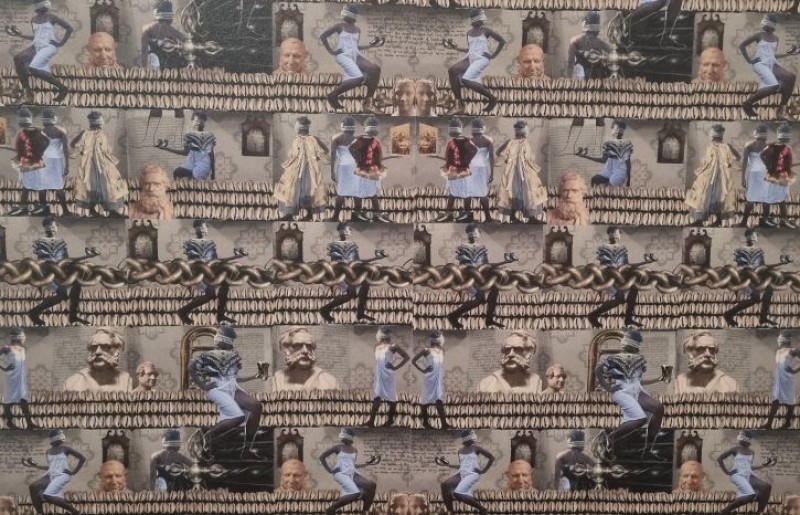

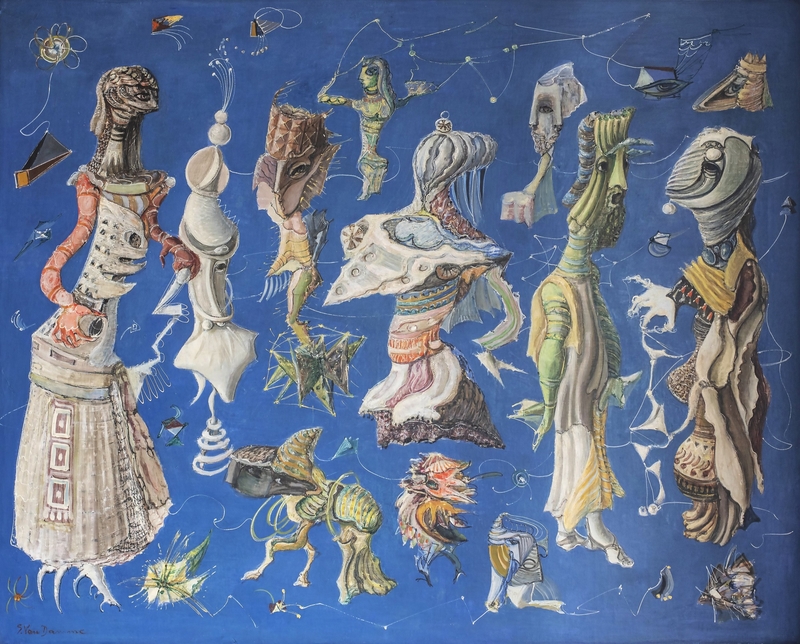

In Stephe Meyler's paintings, subtle expressions of queerness abound, as do the explorations of masculinity within social, political and battle scenes. Inspired by the Napoleonic Period, as well as political and historical events, her work exists beyond binaries, often depicting the politics of alienation or the depersonalisation of the individual in bureaucratic society. I came across Stephe's work while researching for an Art UK story about paintings of Llanelli, and have since struck up a correspondence with the artist.

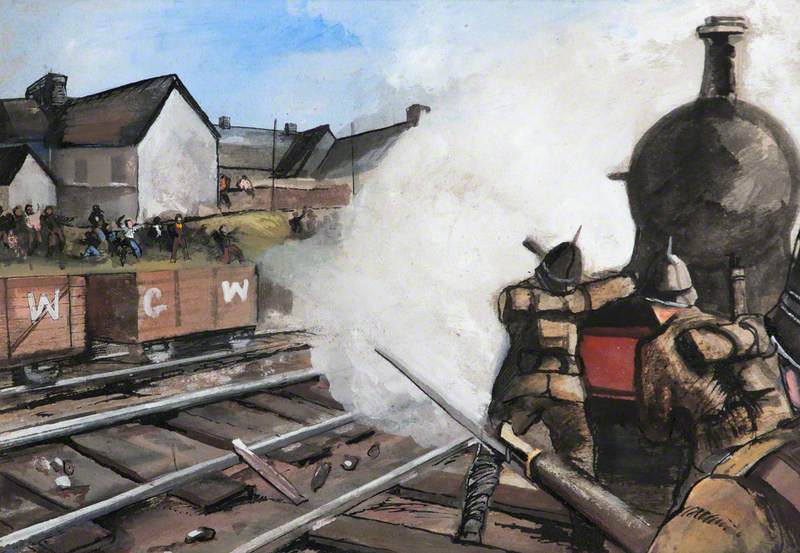

The Riots of 1911, a Reconstruction of the Event

1970s/1980s

Stephe Meyler (b.1956)

Joshua Jones: One thing I like about your work is that you make the political personal. There's what you see on the surface, and the personal expression within the subtext. Can you tell me about your paintings on Art UK?

Stephe Meyler: I was asked to paint something for the cover of a book, Remembrance of a Riot by John Edwards, which I subsequently helped to design. I made a few works about the Llanelli Riots of 1911 – one was a commission by the Llanelli Railway Committee. I also worked on a larger, oil painting about the innocent victims – John 'Jac' John and Leonard Worstell – who were shot dead in their gardens.

I used to be involved in the Labour Party as a young socialist. I had the tendency to be a bit militant in my socialism! Which fed my interest in painting that sort of thing, but not so much anymore.

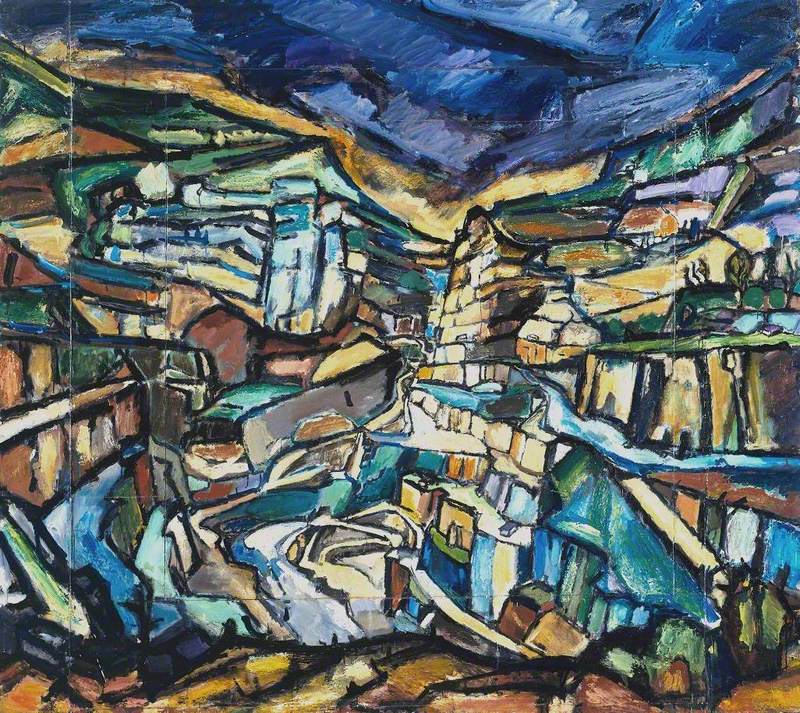

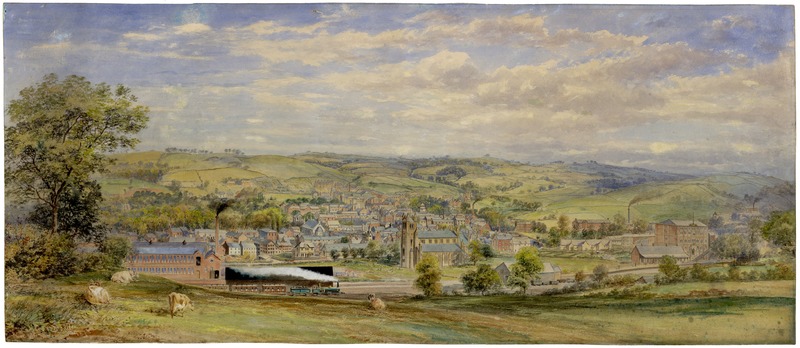

Industrial Landscape started off as a study for a bigger painting. The landscape is based on industry around Llanelli, but it's symbolic too. I wanted it to be both familiar and unfamiliar: hard to place. It could be anywhere. I don't do as many landscapes now. I tend to be more figurative.

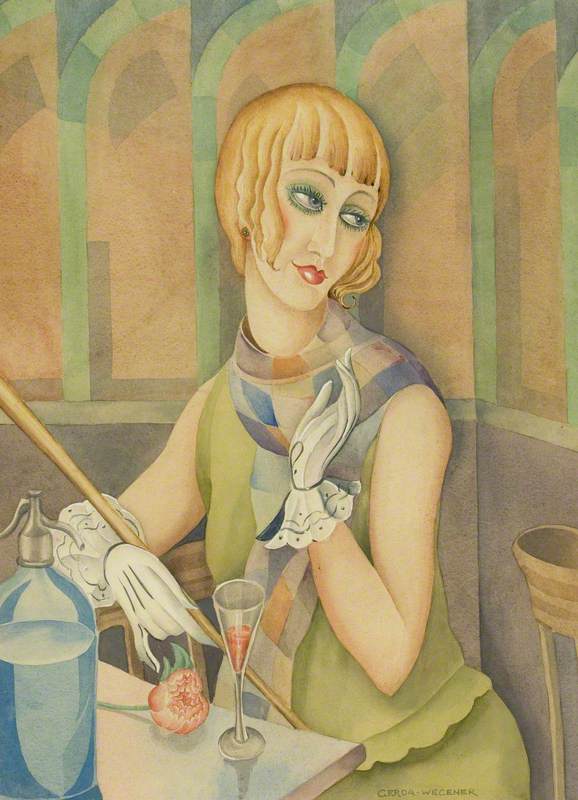

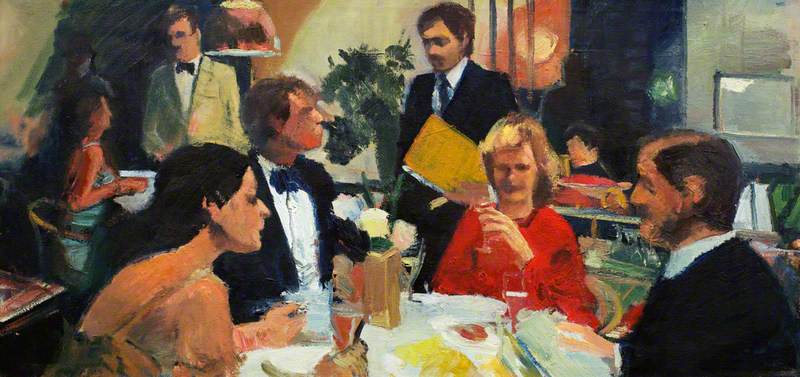

In Dining Out, I was interested in painting what it was like to be seen. In my work I explore the difference between being seen, and simply being – being one thing and seeming another. Dining Out is about that – being observed, being seen to be prosperous and having a good time, but it's also about the people you're with, to be normal and okay.

Joshua: I like that the viewer is positioned as someone returning to their seat at the table...

Stephe: That's right. And no one is looking at each other.

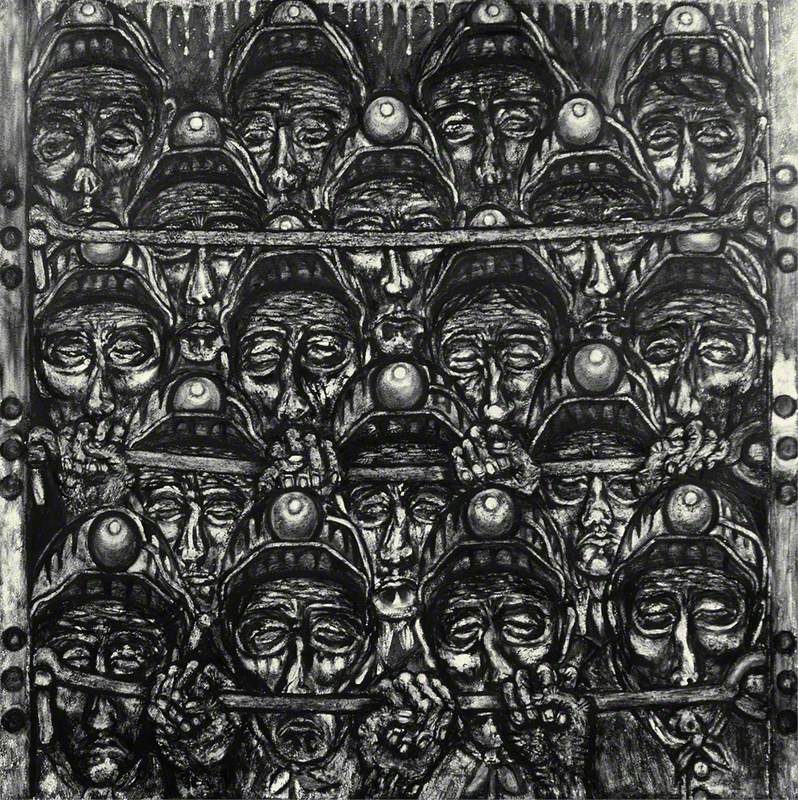

One of the main concerns under Thatcher was the depersonalisation of the individual, especially the worker. I was more politically engaged in my youth but these are still concerns of mine. They're still applicable. I'm interested in the in-betweenness of states and ideas.

Joshua: There's also a sense of neutrality within your work – itself a form of depersonalisation. The position of the voyeur in the work, especially the idea of the queer voyeur, is very interesting. You said you also write poetry – can you say more about that?

Stephe: I've written lots of poems, I write everything down, like a poetry diary. I'm still scared to mention certain things, and to be vulnerable. I think being a queer person, a trans person, means being looked at.

I lost a friend from Llanelli in the Falklands War, so I wrote a poem about him. He protected me at school. He was my Hercules. A boy at school asked me if I was 'bent'. I thought bent meant peculiar, eccentric, individual. So, I said yes. Of course, he meant gay. He said he would rather kill himself than admit to that. The other kids never liked me much – they liked me even less after that! My friend was there for me all through it.

Welsh National Falklands Memorial

2007 or before

unknown artist

Joshua: What was it like growing up in Llanelli as a creative and queer person?

Stephe: It wasn't easy – you couldn't be 'out', really. I used to admire people who were, but I couldn't. Llanelli didn't feel to be a very safe place to be out. Even as a child I felt more inclined to be a woman. As a teenager I tried having girlfriends – I felt like I could relate to them, maybe project my desire for femininity onto them. It didn't work out. I explore sexuality in my work, it's there, perhaps in the undercurrent.

When I went to art college in Carmarthen, the principal saw I was interested in Napoleonic uniforms and he said 'you seem interested in costumes, would you like to study fashion?' I thought it might be interesting. But then I thought, no way! Not in Llanelli. I did a pre-foundation course in fine art there, then a fine art in architecture course, then went on to study at Epsom. The artist Wyn Owens had also studied there. I had hoped I could become more open, especially after going to Carmarthen, but still felt I couldn't.

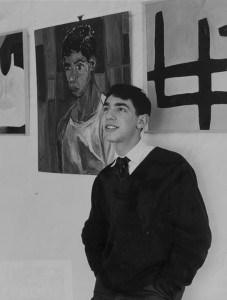

Joshua: Tell me about your early forays into art – what were you making? What were some of your early inspirations?

Stephe: My friend Nigel was very into drawing. We'd scribble with biros at the back of the class. I remember drawing a lot of battles. I was interested in Napoleonic history. The uniforms, the plumes and sashes. Very dramatic – Young Romantics before the Young Romantics! Perhaps there was a sense of overcompensation or projection of identity there, my interest in these hypermasculine worlds and figures, but there was also the tight britches and the boots with the tassels, the big swords. Jacques-Louis David's Napoleon Crossing the Alps is a fine example of what I was interested in. And the film starring Marlon Brando.

The Departure of Napoleon for Elba

Horace Vernet (1789–1863) (after)

Napoleon crossing the Alps

1805, oil on canvas by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825)

Joshua: There's a dichotomy between the hyper-masculinity of the setting, but it's very gay too: the costumes and the muscles. There's so much of that in gay art – Tom of Finland, for example. Was it easier to express yourself as a queer person at Epsom?

Stephe: I hoped I would, but I didn't. The Deputy Head of the Fine Art school was from a military background and not very supportive of queer people. There were plenty of gay students but I felt I couldn't be seen with them. I had a secret world, which I gave expression to, dressing up and that sort of thing. I did enter a drag competition in Carmarthen Students Union with a few friends, once or twice. It was great. My nickname was Nap, after Napoleon. I didn't win – I wasn't as well dressed or as presented as some of the other queens. Everyone voted for the queen with the flashing boobs! We went to the pubs before and I enjoyed that, and how good I looked.

Joshua: What did you go on to do after that?

Stephe: I lived in Epsom for a bit and carried on painting, did a bit of teaching on the side. I applied for a few schools like the Royal Academy but didn't get in. I exhibited at the RBA Summer Show one year.

When I came back to Llanelli, my friend Gareth and a few ex-tutors at the Carmarthen school had formed a branch of the Association of Artists and Designers in Wales. We had a studio by the river that used to be a garage. We had exhibitions called 'Pieces of Eight', and 'Who Carmarthen'. We also exhibited at the AADW branch in Swansea.

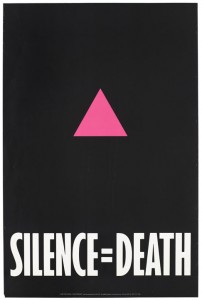

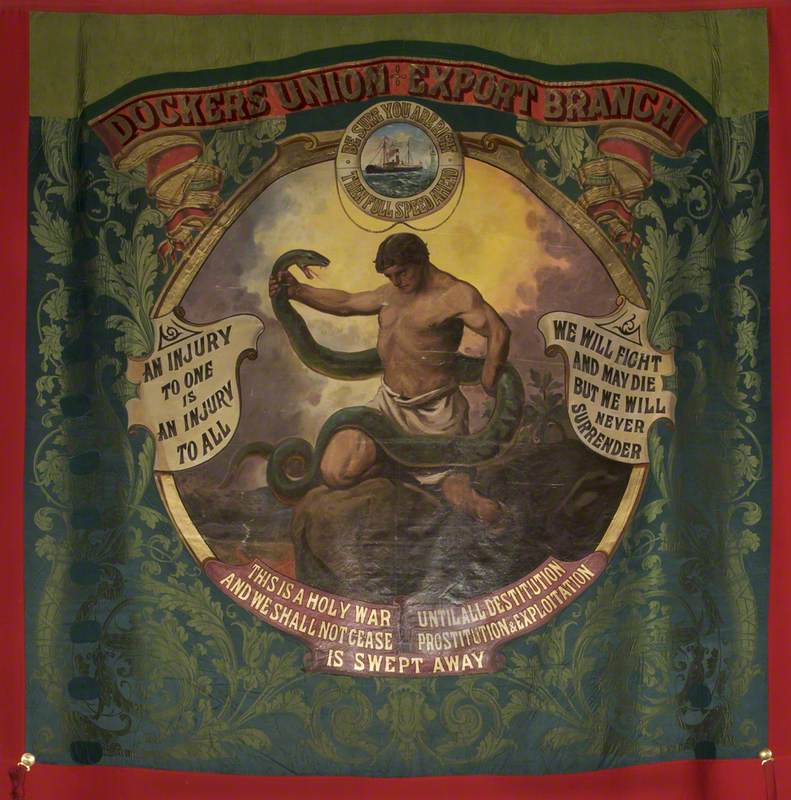

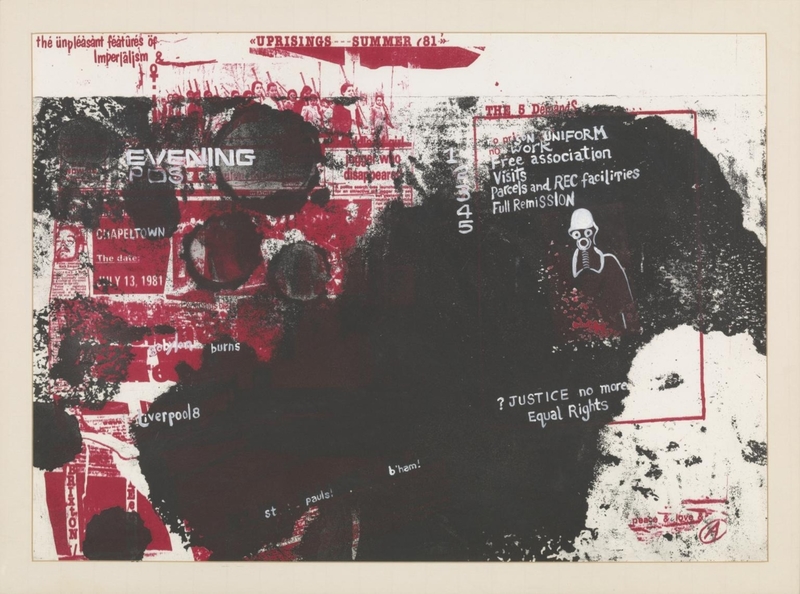

I enjoyed painting – especially good-looking young men! I was painting riots – in the 1980s, there were a lot of riots. I was involved in the miners' strikes, on the picket line. At Cynheidre Colliery the police were out to divide and conquer. They pushed us and we pushed back. It's been 40 years now. I got involved in the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners. I should have been in that film, Pride!

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners

2014, banner created for the film 'Pride'

Some work was exhibited in the London Gays and Lesbians Centre in London, after the miners' strike ended, and I was part of 'Return to Beauty; Figuration in British Art' at the Roy Miles Gallery, in 1994. My work was hung near to Prince Charles's! I had various exhibitions between then, in Wales and elsewhere. I made some paintings about the strike, like Early One Morning – which I think is in the Miners' Hall in Ammanford, if it's still there – a miner getting beat by police. I worked on other paintings about police and riots. I wanted to keep the work general – the idea of protest, repression, but it was personal too. I started going to nightclubs in Swansea, the Palace Theatre. I made some work on those experiences.

I haven't exhibited much lately, but I'm still painting. I painted all through the coronavirus lockdowns, responding to the news on the TV. I painted queer bodies within these settings. I painted about asylum seekers on boats, seeking refuge. I've painted scenes about the war in Ukraine and Gaza. I paint as if responding to historical events while they're still happening.

Joshua Jones, writer

Stephe's work is in the collections of Parc Howard Museum and Carmarthen County Hall, both of which are part of Carmarthenshire Museums Service Collection

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

.jpg)