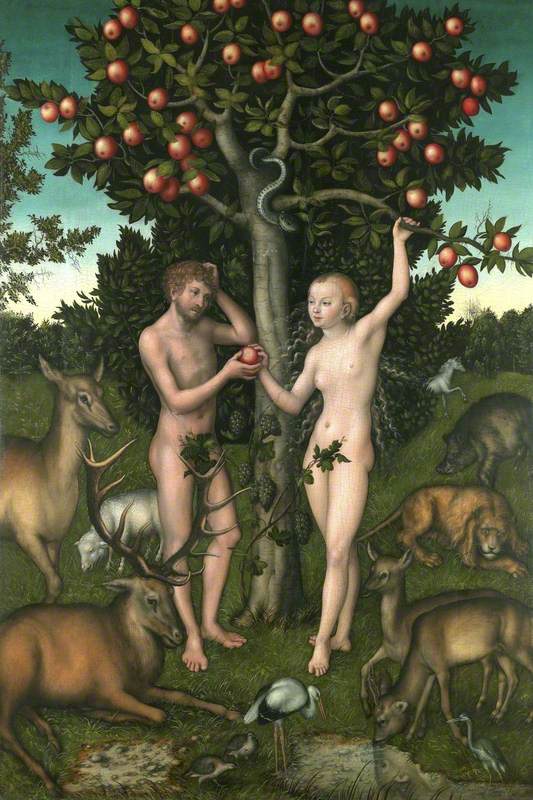

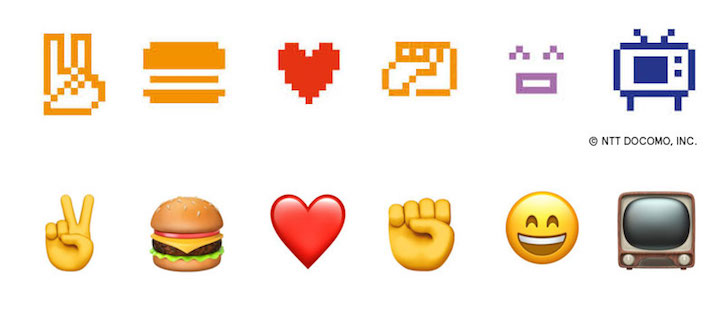

The original 176 Emoji that had been added to The Museum of Modern Art’s collection.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Don't think emoji are a serious topic? Well :raised hand: emoji, because the Museum of Modern Art in New York would beg to differ. In 2016, the MoMA acquired the original set of emoji distributed by NTT Docomo for their collection and two years prior to that, an emoji version of Herman Melville's Moby Dick called – get ready for it – Emoji Dick was acquired by the Library of Congress.

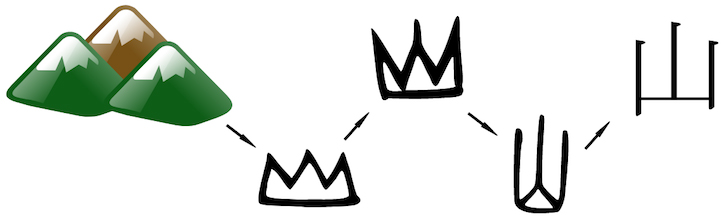

Visual expressions of language extend back millennia, be they the hieroglyphics of Egypt or the early ideograms of languages across Asia, Africa and the Americas. Images have the ability to cross language barriers and transcend literacy challenges to quickly convey ideas. And, not to over-intellectualise the topic, emoji are just plain fun to use.

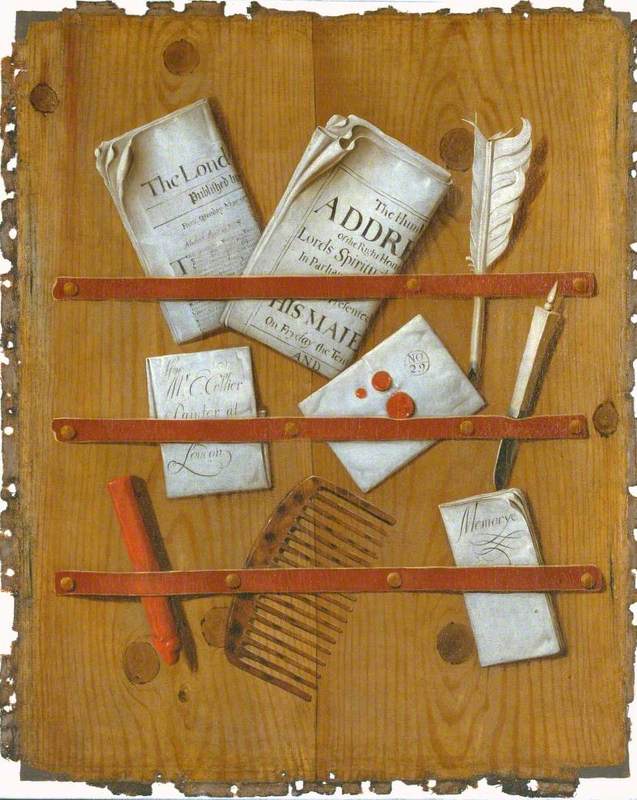

Evolution of 山 shān, the Chinese character for mountain, from early pictograms to the contemporary simplified Chinese character.

The evidence of emoji's social impact is clear in the presence of the images in popular products and media – the highly respectable actor Patrick Stewart played the poop emoji in The Emoji Movie, for goodness' sake. If institutions like the MoMA can see enough cultural merit in the symbols to collect them, I'm certainly curious to know more about their origins and significance.

'Emoji are part of a long evolution of including images and abstract shapes within text,' says Paul Galloway, Architecture & Design Collection Specialist at the MoMA. 'Think of illuminated manuscripts – there's always been a desire to embellish written text with images.'

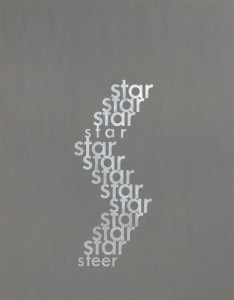

The direct predecessor to emoji were emoticons, which are facial expressions constructed with punctuation and marks. The first use of an emoticon with the intention of conveying emotion is frequently attributed to Scott Fahlman in 1982 when he used :-) and :-( with text explaining how they could be used. Western emoticons remained quite simple in comparison to the Japanese counterparts that would follow, called kaomoji. Kaomoji – which means 'face characters' – incorporate symbols from Japanese writing systems to create more elaborate designs such as this cheeky face: ( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

Over time, Japanese designers sought to push kaomoji further by finding better ways to use expressive symbols on early mobile devices. Despite colour and pixel restrictions, companies began to develop the early emoji designs, with the first being a ♥. The NTT Docomo set of emoji acquired by the MoMA were the most successful of those early emoji sets. Now is a good time to mention that the term 'emoji' is a Japanese word meaning 'picture character', and is not related to the word 'emotion', as is widely believed.

A selection of NTT Docomo emoji designs versus their 2019 iOS 12.2 equivalents.

'Here at MoMA, we wanted to wind the story back to the creation of emoji in Japan in the 90s to... point out the extremely specific Japanese character and nature that defines the early emoji set,' says Paul. 'It is the reason why there's still so much Japanese flavour to the emoji set.'

Emoji, as we know them today, are steadily evolving, with new designs added each year. Changes to the set often reflect people's desire to see themselves represented in the icons. The addition of skin tones, different hair types, and the woman in a headscarf are some examples of the socio-cultural significance we place on emoji. It's also interesting to see how, in the absence of a desired symbol, communities co-opt existing emoji for other meanings. Sometimes this is light-hearted, like the use of a peach to represent a bum, but this is exemplified in the alt-right's more nefarious use of the okay-hand emoji. The challenge for emoji moving forward will be how to create a set representative of the world around us that doesn't grow beyond the scope of easy usability.

To hear my discussion with Paul about the history and impact of emoji, click the player or links at the top of this story.

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes