Download and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Within western art history, images of food can be found in the ancient world, including Egyptian tomb paintings, Roman mosaics and more, but it was not until much later that we began to see still life paintings of food in the way that we think of them now. Due in part to advances in materials, we begin to see realistic depictions of flowers and fruit in the early Renaissance.

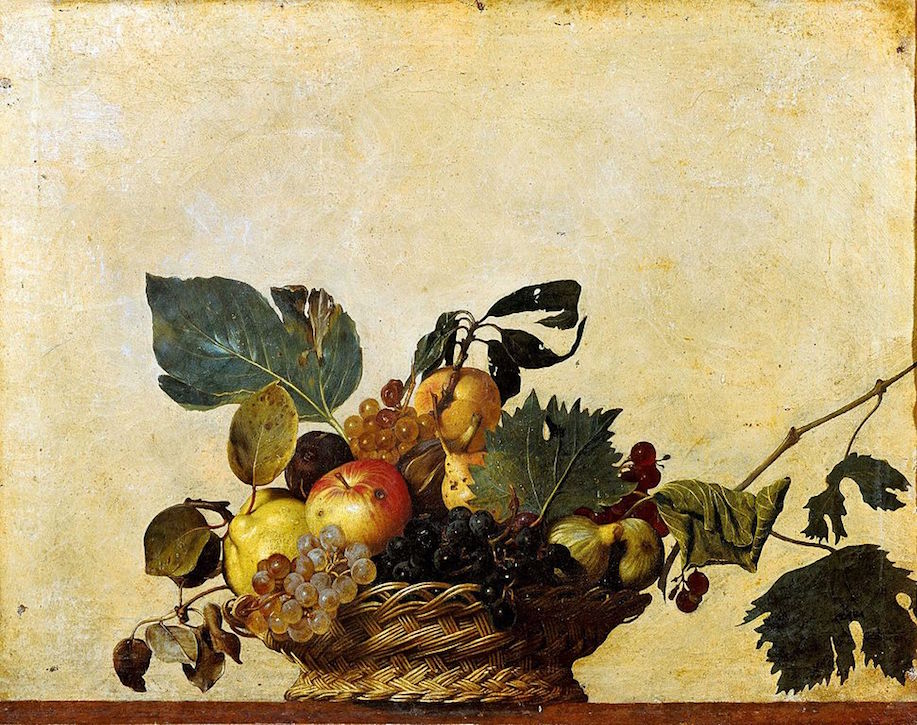

'This was a culture that was used to grand history themes and religious iconography,' says food historian and artist, Tasha Marks. 'To paint a basket of fruit as Caravaggio did in 1599 was quite a revolutionary thing to do. He was also imbuing that image with symbolism, so it wasn't just a basket of fruit, it was about storytelling.'

Canestra di frutta (Basket of Fruit)

c.1599, oil on canvas by Caravaggio (1571–1610)

Caravaggio's painting shows a wicker basket filled with a mix of grapes, apples, pears and figs. At first glance, it is a rather appealing selection of fruit, but on closer examination, we see that the apple and some of the leaves have wormholes and there are other signs of decay and overripeness in the fruit. The image could be a metaphor for the temporal nature of life or fading beauty. We see a similar still life appear in Caravaggio's painting Supper at Emmaus, where Jesus appears to two disciples after his resurrection. In each painting, the basket teeters just over the edge of the table, creating a feeling of precariousness. As viewers, we get the sense that these images are not just visual documentations of fruit, but a metaphor.

The size and sophistication of these images grew in the sixteenth century, particularly with the Dutch and Flemish masters. At this time, we see food still lifes incorporated within larger market, kitchen and shop scenes. A series by Joachim Beuckelaer in the National Gallery collection represents the four elements of earth, air, water and fire through depictions of foods associated with each. The four paintings are crowded with detailed images of vegetables, meat and cooking utensils, creating a feeling of abundance. For a period, artists tried to maintain a degree of religious subtext in these works – as was common in art of the time – but eventually, these works came to stand alone as genre scenes and elaborate still lifes.

'For that genre to be mastered by a group of painters meant that their status went up and it became very desirable,' says Tasha. 'It became something that everyone wanted to have in their homes.'

Part of the fun of viewing still life paintings is deciphering the meanings they potentially hold. In our episode on animals in art, we spoke about how some animals can be metaphors for ideas, such as a boar as a symbol of gluttony or a dove for the Holy Spirit – the same can be true for symbolism in representations of food. Some items make frequent appearances in these paintings, such as lobsters or lemons, and they each carry potential meanings to tell a story.

'If we look back through various texts, the lemon, for instance, could be a simple of luxury and love and longevity, but then it's also about sourness and disappointment,' says Tasha. 'It's a two-sided thing – even something as simple as a lemon. Also, it could be that a lemon peel unfolding and twisting around the scene was a way for the artist to show off their skills.'

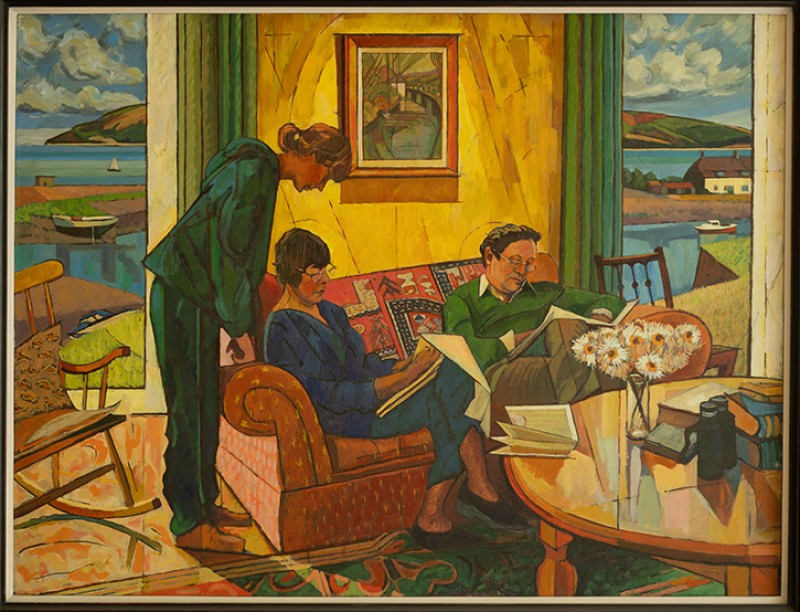

The Interior of an Inn ('The Broken Eggs')

about 1665-70

Jan Steen (1625/1626–1679)

A seventeenth-century painting by Jan Steen titled The Interior of an Inn ('The Broken Eggs') shows a merry tavern scene with a young woman standing next to three men. One man laughs heartily while tugging at her skirt while the other two look on. The food in this scene gives us a hint at what is happening – the phallic symbol of a pan points towards the man grabbing the woman's skirt, and broken eggs and oyster shells lay on the ground. Oysters are often said to be an aphrodisiac and broken eggs were sometimes used at this time to symbolise the loss of a woman's virtue. The woman attempts to pull the man's hand away and we can surmise that the artist – who used his own likeness for the laughing man – is hinting at the man's lustful intentions.

Another food rich in symbolism in still life paintings is the pineapple, which can add texture and visual interest to a still life, but also implies luxury and wealth.

'A pineapple, when it first arrived in the UK was a very exclusive object. They were being shipped overseas and they had often survived a very long journey,' says Tasha. 'I think the first pineapple that arrived in England was a single pineapple that was the only one that survived the journey. It was presented to the king, who declared it the best fruit in all the world, so there was pineapple mania from the very [beginning].'

A painting by Thomas Stewart in the National Trust collection exemplifies the significance of pineapples in earlier centuries. A royal gardener is shown on bended knee presenting a pineapple to Charles II (there is some debate around whether the painting depicts the first pineapple grown in England). The delicacy with which the gardener presents the fruit to the monarch conveys how special and luxurious it would have been at the time. The foods that artists chose to immortalize through painting give us insight into the items that people valued, the way that they ate, and how varieties of some foods have changed over the centuries.

While there was more than one watermelon breed available in Europe in the seventeenth-century, there are several paintings from this period that display watermelons split in half with the white of the rind surrounding pockets of the red melon and seeds in a star-like fashion. The presence of these curious watermelons alongside paintings of melons closer in appearance to what we are used to today give a visual history of selective breeding practices.

We can see an example of the older breed of watermelon in a playful image by Guiseppe Arcimboldo called Summer. The artist is famous for his portraits of people composed of fruits, flowers, and other items. In Summer, he uses summer fruits to make the head and torso of a man, bringing a whimsical energy to the traditional still life. A pear serves as the figure's nose, plums make up the collar of a blouse, a watermelon sits on the stomach, and so on.

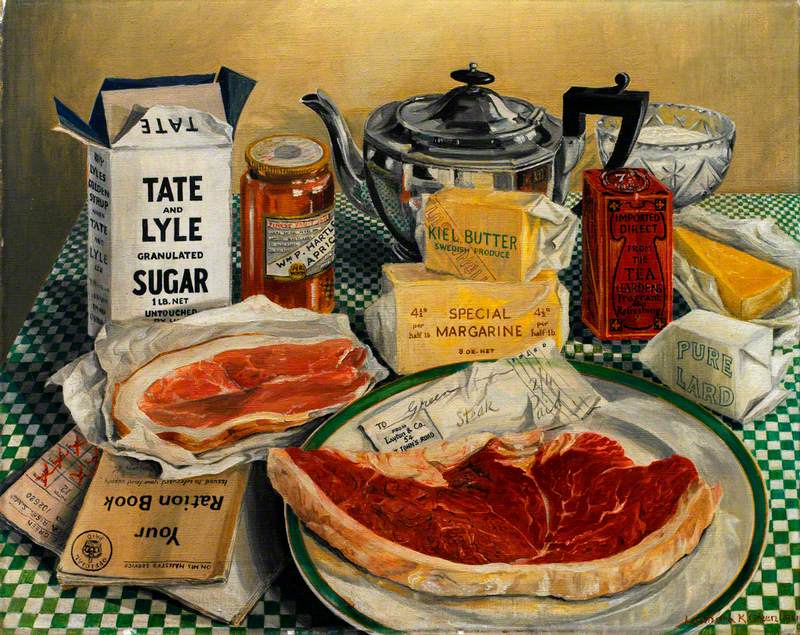

Turning to the modern era, we can still look to still life images to learn about a society's changing relationship with various food items. Let's discuss the 1941 painting Coupons Required by Leonora Kathleen Green in the Imperial War Museum Collection.

'It shows a selection of foods that you would have needed coupons for [during] rationing and shows the idea of everyday foodstuff being something that is super desirable,' says Tasha. 'We learn about perspective through foodstuffs and what people think is important.'

Whether it is Paul Cézanne experimenting with perspective through painting still lifes of oranges or Andy Warhol commenting on American consumerism with an image of a Campbell's soup can, artists have continued to use food as a subject through to the present day. With a little knowledge of the history of some foods, we can extract deeper layers of meaning from these artworks.

'Eating is a performative act,' says Tasha. 'It focuses on a lot of things like behaviour and ritual, and if you're using that as a medium – whether you are painting a still life or you are doing a performance with food – you are reaching a much wider audience in a way that is innately human, and I think that's what makes it so powerful.'

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes