Ask any dog lover to show you a photograph of their pet, and they'll whip out their phone and scroll through a camera roll of thousands of images to find you the perfect picture. We love our dogs, and we love looking at pictures of them.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Loyal Subjects: A Bust of Queen Victoria Surrounded by Some of Her Dogs

Frances Caroline Fairman (1839–1923)

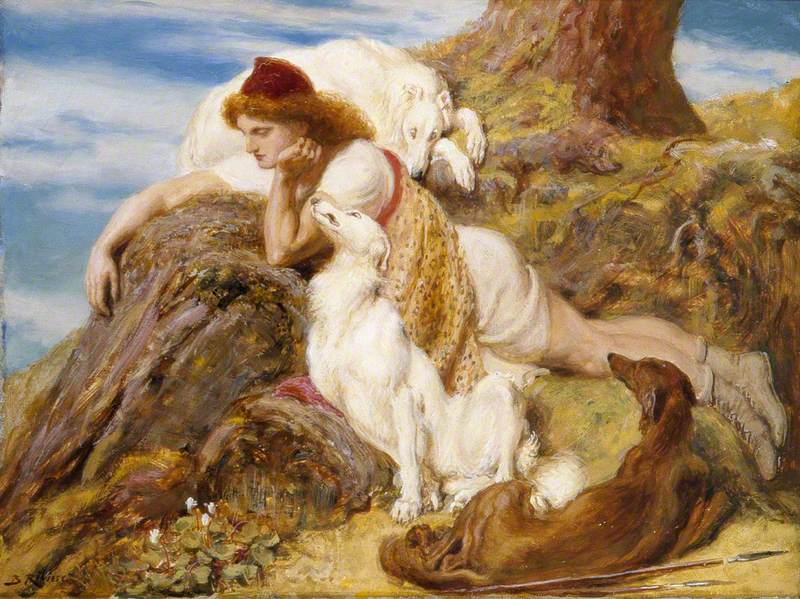

National Trust, Hinton AmpnerAs one of the first animals to be domesticated by humans, dogs have long attracted the eye of professional and amateur artists alike. They frequently crop up as accoutrements in many of the most iconic paintings in the UK's public art collections. Sometimes they give the viewer a clue to a human subject's personality or lifestyle. Sometimes they represent fidelity. And sometimes they just give a potentially awkward sitter something to do with their body while posing for an artist.

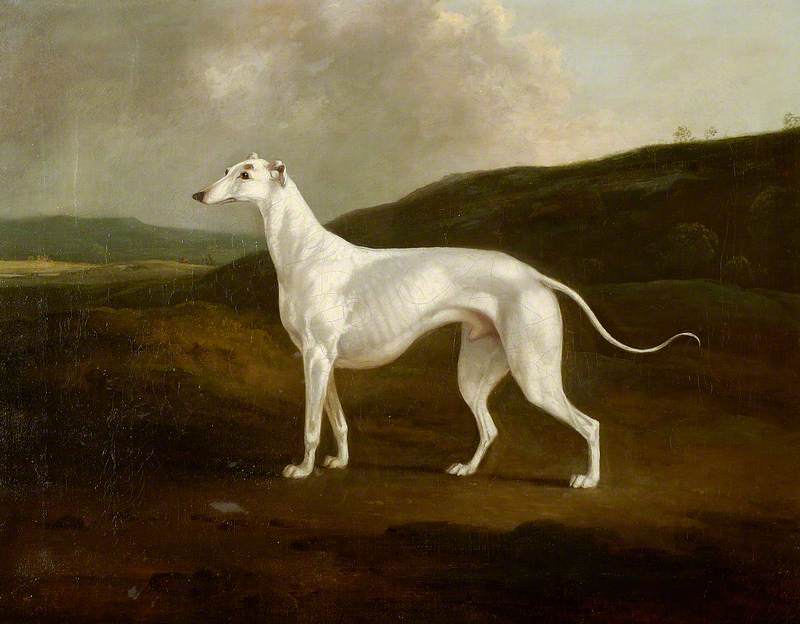

But around the end of the seventeenth century, dog owners in Britain and elsewhere in Europe began to commission portraits celebrating dogs on their own, without humans. Such paintings were only a realistic prospect for the wealthiest dog owners in Britain and dog portraits in the UK's public art collections disproportionately represent the companion dogs and hunting hounds kept by society's elite.

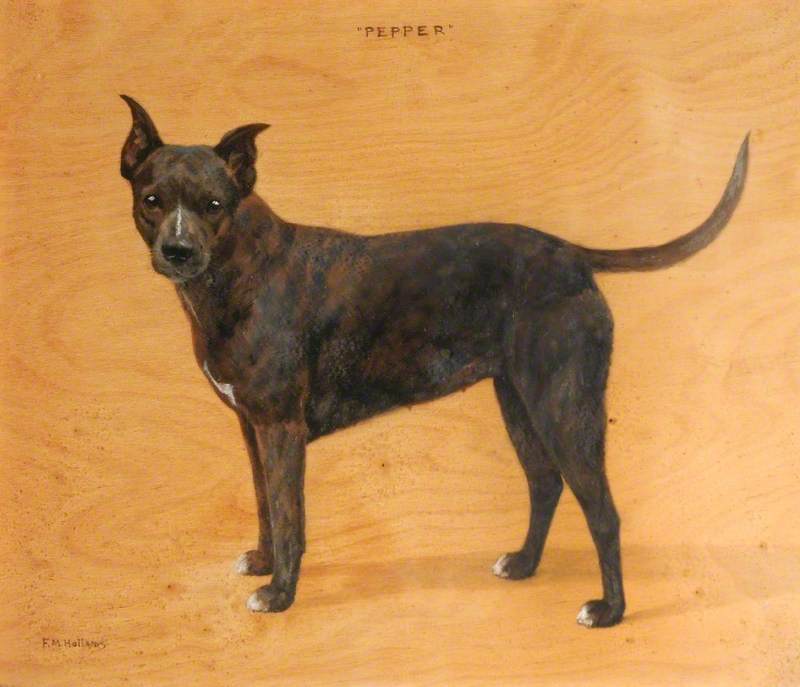

These paintings are portraits in the truest sense, intended to be accurate likenesses of specific individual dogs, often identified by name. Crucially, many of the subjects of these paintings were dogs who weren't special for performing unusual feats, their illustrious ancestry or for their rarity. Often, they were only special to their owners simply because they were loved.

Image credit: National Trust Images

A Dutch Mastiff (called 'Old Vertue'?) with Dunham Massey in the Background 1690s

Jan Wyck (1645–1700)

National Trust, Dunham Massey

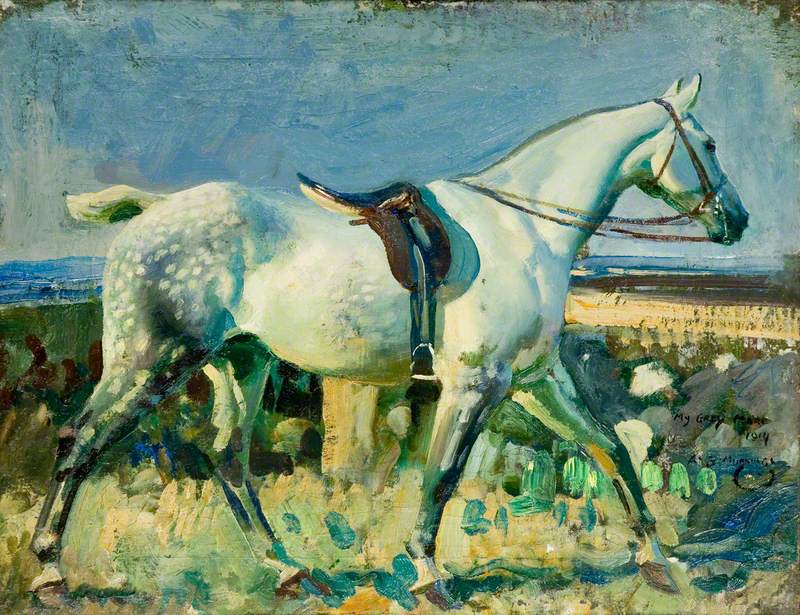

One of the first of the new breed of dog artists was John Wootton (c.1682–1765), an artist who specialised in painting horses and hunting scenes. Around 1740, he began to take commissions from people who owned dogs for companionship.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Dancing Dogs: 'Lusette', 'Madore', 'Rosette' and 'Moucheby' 1759

John Wootton (c.1682–1764)

National Trust, WallingtonAmong his canine sitters was a little black-and-white dog, the pet of Margaret Cavendish, 2nd Duchess of Portland. Painted around 1741 and now in the collection of the Tate, there's absolutely nothing obviously remarkable about the dog, but here she is depicted in a lush garden in a grand classical landscape in the background. On the left of the dog is the base of a column engraved with a name – Muff.

Muff may be the name of the subject of the painting or perhaps a nod to a departed doggy companion. An identical dog named Mina appears in a portrait-within-a-portrait of her daughter, Casey, in another work by Wootton in Nottinghamshire's Portland Collection.

Such portraits were at least partially intended to be humorous, contrasting the unassuming appearance of these little dogs with the grandiosity of their antique surroundings. But if these paintings were intended purely as jokes, the punchline was an expensive one. They were certainly often of considerable sentimental value. Wootton's portrait of Patapan, a little white dog owned by Horace Walpole, remained on display in the writer and antiquarian's bedroom beside artwork by and of his family and close friends long after the much-loved dog's death.

Wootton was not the only eighteenth-century artist to dabble in dog art. A string of artists (of varying skill) specialising in animal painting followed him in earning reputations as painters of dogs. For instance, while George Stubbs is best remembered for his large-scale paintings of prize-winning racehorses and exotic beasts, he was also very much in demand as a portraitist of dogs.

The development of the canine portrait reflected the changing status of dogs in British society. In her 2015 study of pets and social change in eighteenth-century Britain, cultural historian Ingrid Tague observes that a 'new sense of animal subjectivity encouraged the spread of portraits of pets as individuals in their own right'. In the next century, dog portraiture continued to increase in popularity, buoyed by the development of the movement for kindness towards animals and an increased acceptance for dogs as household pets.

Dog portraiture also reflects how dogs themselves have been changed by humans. The nineteenth century saw the birth of the modern dog 'breed' as we understand it today. According to historians Michael Worboys, Julie-Marie Strange and Neil Pemberton, the difference between dogs before and after the development of the idea of dog breeds 'can be compared to how colours appear in a rainbow versus on a modern paint sample card'.

Whereas dogs were once grouped into very broad categories with some overlap between them, from the nineteenth century onwards dogs have been categorised into distinct, standardised types. British art reflects not only an explosion in the numbers of new dog breeds, but also the fluctuating popularity and changing shapes of individual breeds.

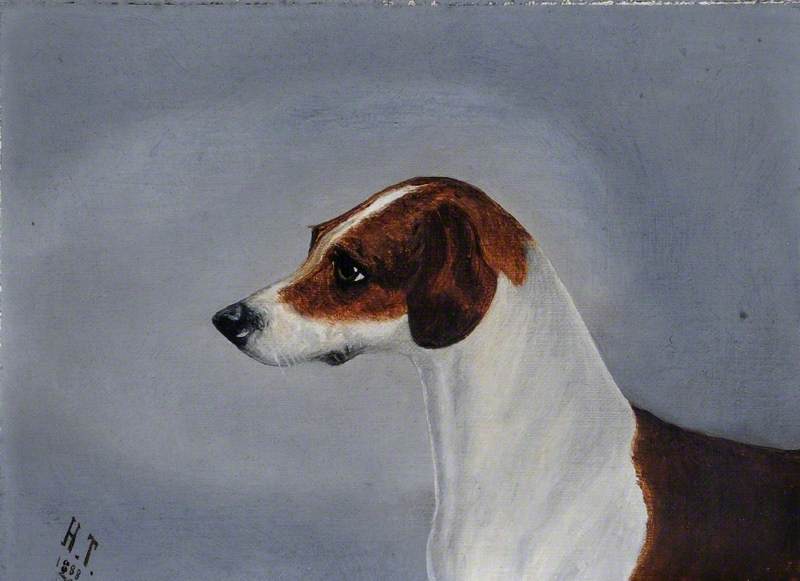

Dog shows became popular in the later nineteenth century and dog showing remained a very fashionable activity well into the mid-twentieth century. Portraits of champion show dogs – such as the 1902 painting of a prize-winning Gordon Setter by the leading dog artist Maud Earl – are both portraits of individual dogs and depictions of an ideal specimen of their whole breed.

Image credit: National Trust Images

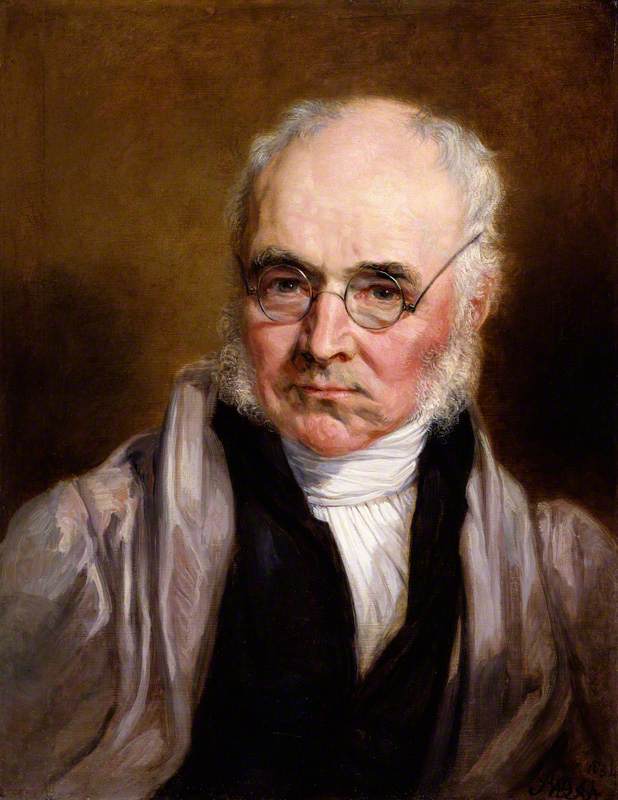

Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873) (after)

National Trust, Anglesey AbbeyThe birth of the pedigree dog was just one way in which dogs' position in nineteenth-century society was in flux. During the Victorian period, dogs became even more firmly ensconced at the centre of domestic life and the idealised family. Queen Victoria, herself a dog lover, had the royal family painted surrounded by their pack of pets. Her favourite animal artist, Sir Edwin Landseer, was knighted in 1850 – the same year he painted Victoria's own spaniel, Tilco.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Queen Victoria's Spaniel, 'Tilco' (d.1850) 1838

Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873)

National Trust, Anglesey AbbeyLandseer's dog paintings, along with those of his imitators, often anthropomorphise dogs. Often, his dogs act out situations from in human society (sometimes commenting on or reflecting human prejudices of the day). Likewise, he had a tendency to endow the subjects of his canine portraits with what seem to be particularly human emotions and impulses.

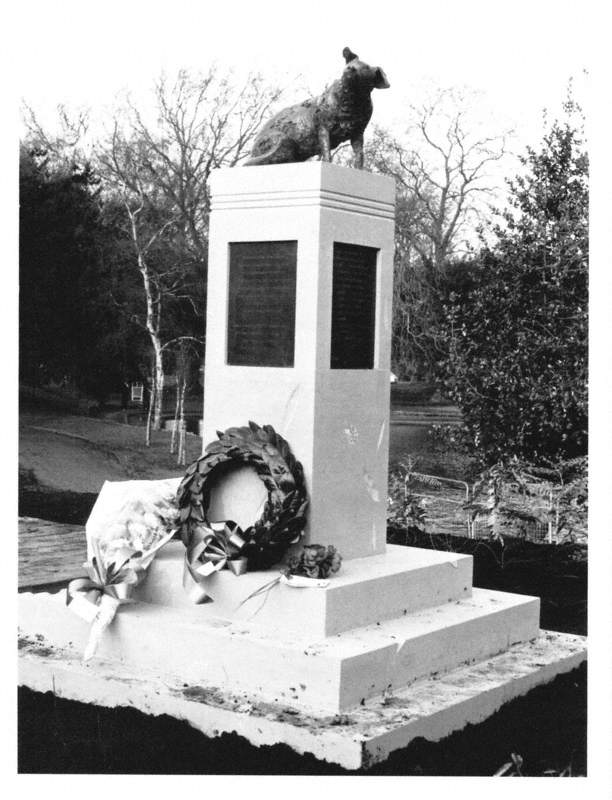

One of Landseer's most famous paintings, A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society, depicts a black-and-white Newfoundland dog, Paul Pry, lying on a quayside. Painted in 1838, it celebrates another Newfoundland named Bob who had been honoured by a lifesaving charity for rescuing people from drowning in the Thames. Its title winkingly blurs the boundaries between species – the dog's actions are more humane than those of many humans.

Although the dog is less anthropomorphised than many others painted by Landseer, his heavenward gaze nevertheless suggests, in the words of art historian Diana Donald, 'a preternatural consciousness of moral duty'.

During his lifetime Landseer's art was tremendously popular – according to Donald, his 'paintings of dogs were the Victorian public's favourite works of art'. Originals and copies alike hang in galleries around the UK (there are at least four copies of A Distinguished Member in public art collections alone).

Image credit: Great Yarmouth Museums

A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society (after Edwin Henry Landseer)

William Henry Ruggles (active 1833–1846)

Great Yarmouth MuseumsTo this day, black-and-white Newfoundlands are known as Landseers. Prints of his paintings were made for mass consumption across the world. These days, however, Landseer's work (and animal art in general) is often derided as kitschy and accused of trading in cheap sentimentality. Nevertheless, the attitudes reflected in Landseer's paintings – a belief in the inherent goodness and nobility of dogs (we might even say their 'humanity') – have become embedded into our cultural consciousness and are still very much alive in Britain today.

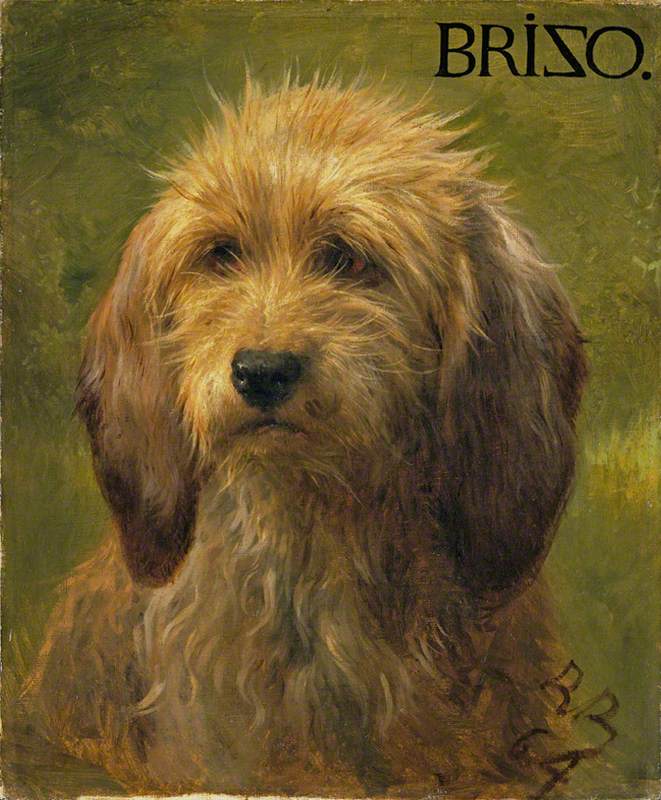

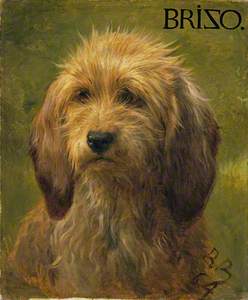

While British collectors were often drawn to the work of animal artists from Britain and continental Europe (for instance, an 1864 portrait of a shepherd's dog named Brizo by the leading French animal artist Rosa Bonheur hangs in London's Wallace Collection), there is often a considerable gulf in a piece of dog art's sentimental appeal to its owner and its aesthetic value in the eyes of connoisseurs.

In 1919 a Scottish engineer named James Cowan Smith bequeathed £50,000 (roughly equivalent to £2 million today) to the National Galleries of Scotland. There was just one condition – a portrait of Cowan Smith's Dandie Dinmont terrier would have to go on permanent display.

John Emms's 1895 painting depicts Callum, bright-eyed and alert, with a freshly-caught rat at his paws – a testament to his skill and heritage as a ratting terrier. Callum's portrait has now hung at the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh for over a century.

The gallery's trustees were not impressed with the portrait and even debated whether to accept the bequest. However, they eventually relented. Members of the public have Callum and his portrait to thank for their enjoyment of the art (including work by Francisco Goya, J. M. W. Turner and Diego Velázquez) purchased with funds from Cowan Smith's generous donation.

It is easy to dismiss dog art as sentimental, vulgar or trivial – as, perhaps, the Scottish National Gallery's trustees did a century ago – but it offers a testament to the long-lived and deep bonds between people and dogs. Perhaps more importantly, it also reminds us as viewers that our relationships with dogs (and even the bodies of the animals themselves) are a product of our shared historical moments.

Dr Stephanie Howard-Smith, historian of human-dog relations

Further reading

Diana Donald, Picturing Animals in Britain, 1750–1850, Yale University Press, 2007, pp.127–136

Ingrid H. Tague, Animal Companions: Pets and Social Change in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Penn State Press, 2015, p.181

Charlotte Topsfield, 'The Cowan Smith Bequest: How a Dandie Dinmont Terrier helped to build Scotland's art collection', National Galleries Scotland, 2019

Michael Worboys, Julie-Marie Strange and Neil Pemberton, The Invention of the Modern Dog: Breed and Blood in Victorian Britain, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018, p.2