Anthony Whishaw RA was born in England in 1930, but spent the first nine years of his life in Brazil, until, with war looming, he returned with his mother to the United Kingdom in 1939. At fourteen, he won a place at Tonbridge School in Kent, where he was a keen sportsman, playing rugby, squash and fives. When he was sixteen, he fractured his skull playing rugby, forcing him to give up team sports and instead turn towards painting and drawing, creating cartoons of the teachers and school life that demonstrate the sense of humour and wry outlook of life we still find in his work today.

In 1948 Whishaw left Tonbridge and began to study at Chelsea School of Art. Everything he had previously known about painting was challenged. Encouraged by his teachers, Ceri Richards and Prunella Clough, he began to expand his horizons and become more adventurous in his practice.

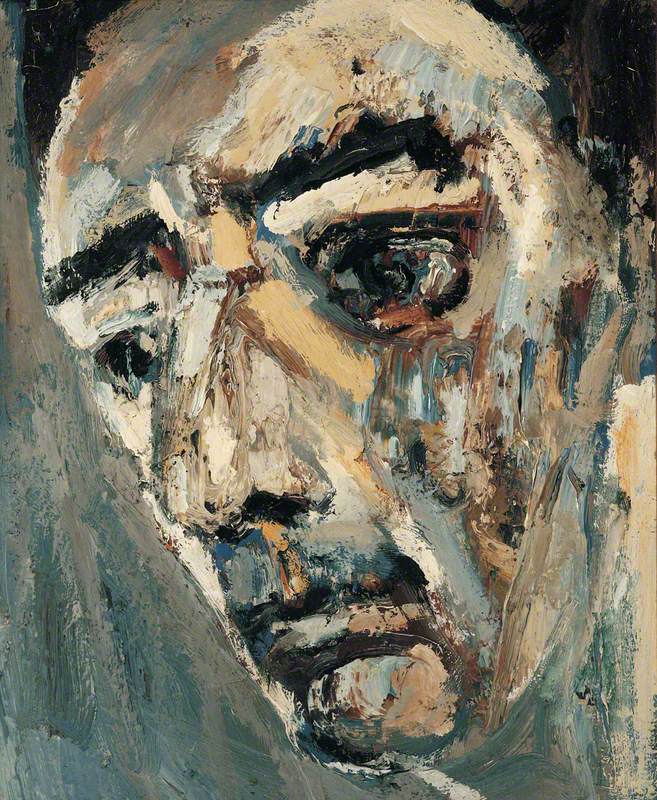

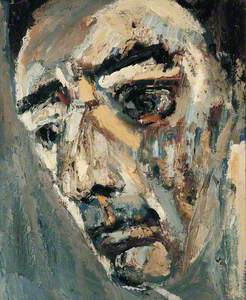

In London galleries he discovered artists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque and a new, dynamic way of treating the human figure and manipulating pictorial space. Picasso's use of tortured bodies and angular, cubist features also showed Whishaw how to communicate an emotional reality rather than a likeness.

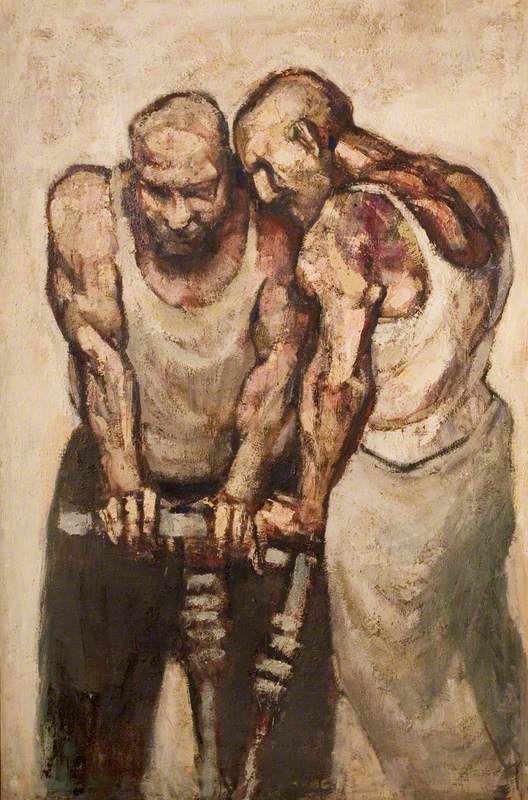

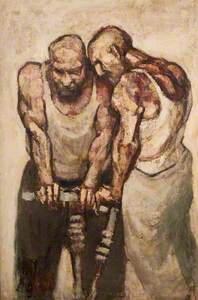

The Belgian painter Constant Permeke was also an important early influence on Whishaw's paintings. Frequently dealing with death and old age: two old men sitting at a table playing cards or eating, studies of dead fish, portraits of elderly figures, crucifixions and Last Suppers, matadors and bullfights –thickly applied oil paint seems to sculpt the figures into being giving them a three-dimensional solidity. Movement is implied by a dynamic pose that captures a moment of frozen drama.

Just before his final year at Chelsea, Whishaw went on holiday to Ibiza, starting a lifelong passion for Spain. If 'Paris' and Permeke had shown Whishaw how to paint reality, Spain offered him a reality he felt compelled to paint. For a young student who had spent his childhood in South America and who still felt more foreign than British, the raw passion and energy he discovered in Spain cast an unforgettable spell. Fascinated by the pageantry and rituals, compelling narrative and dynamic shapes of the bullfight, he drew the horses and bulls, the matadors and the cheering crowds.

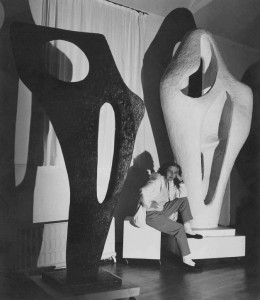

At the end of his four years at Chelsea, Whishaw won a place at the Royal College of Art, where his contemporaries included Bridget Riley and Frank Auerbach. When his tutors told him that he needed to go away and learn how to draw, he did just that, working in his studio off-campus rather than in the College, only attending tutorials and Life Classes.

View this post on Instagram

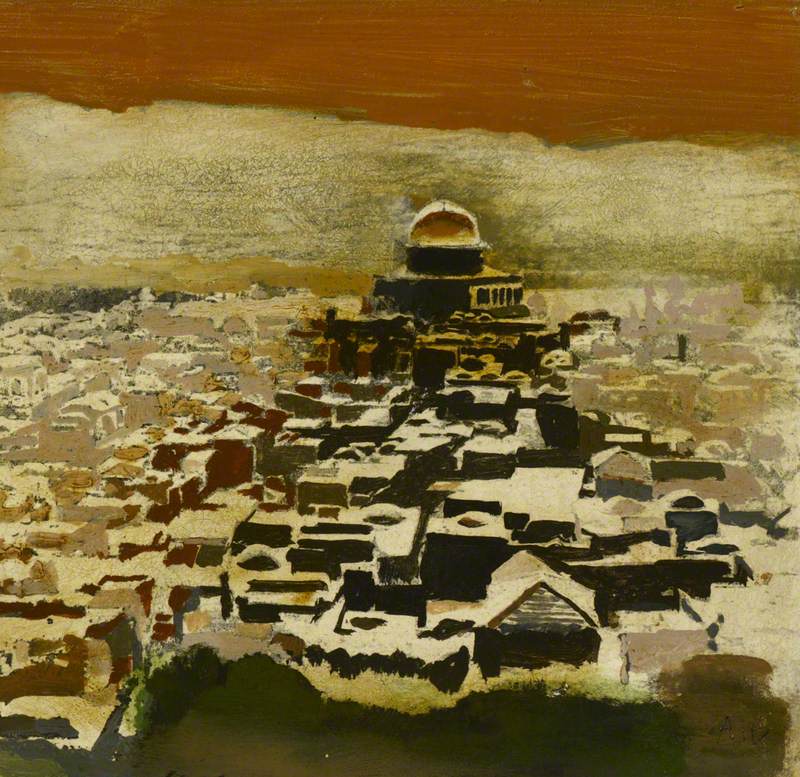

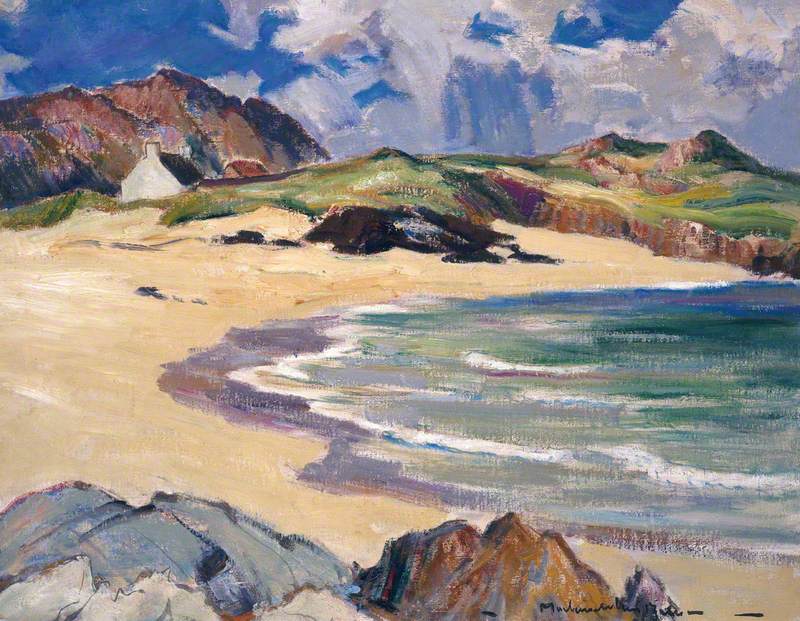

When Whishaw left the College, he was awarded a Royal College of Art Travel Scholarship, an Abbey Minor Travelling Scholarship and a scholarship from the Spanish Government. He bought a Lambretta scooter and went to Spain. Riding along rural Spain's dusty, often unmade roads he would stop to make quick sketches of a hilltop town, reducing the buildings to the same broad strokes that he later used to give form to the elderly men he saw drinking in bars in the sun-drenched squares.

Back in England, in the late 1950s Whishaw was one of the tens of thousands who joined the Aldermarston marches organised by the newly formed Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Yet, as he marched, he began to feel suffocated by the huge crowds around him. He felt that he was losing his identity, reduced to being nothing more than a terrified, faceless form in the crowd. His work began to reflect this feeling. His figures, whether dancing or standing in crowds, began to lose their individual identity, subsumed into a larger undergrowth of tangled lines and vague amorphous shapes, an indeterminate space that shifts between two and three dimensions, form and formlessness.

We glimpse moments of solidity, a suggestion of physicality and a familiar form, but then they disappear, or we may see a horizon, but then we notice another and then another –the single perspective turning into many viewpoints. He plays with size and scale, interrogates surface and depth, uses colour to create spatial playfulness and questions what is solid and what is insubstantial. Lines and marks begin to exist in their own right as instances of abstract energy rather than tools of figurative representation.

Towards the end of the 1960s, confronted by the emergence of Abstract Expressionism, Whishaw felt himself entering a crisis of confidence – what was he doing and why was he doing it? Not only did he doubt his use of oil paint, but he found himself reassessing everything – his intentions, influences, and role as an artist.

In 1968 he left his Cork Street gallery Roland, Browse and Delbanco, wanting the freedom to experiment, without the pressure to produce work for collectors who he felt just wanted more of the same. This coincided with the most significant change in his practice – he stopped painting in oils and turned to the relatively new medium of acrylic. This proved to be a moment of liberation. Because it dried quickly, he could try things out and test ideas. Paint was no longer Whishaw's tool, it had also become his subject.

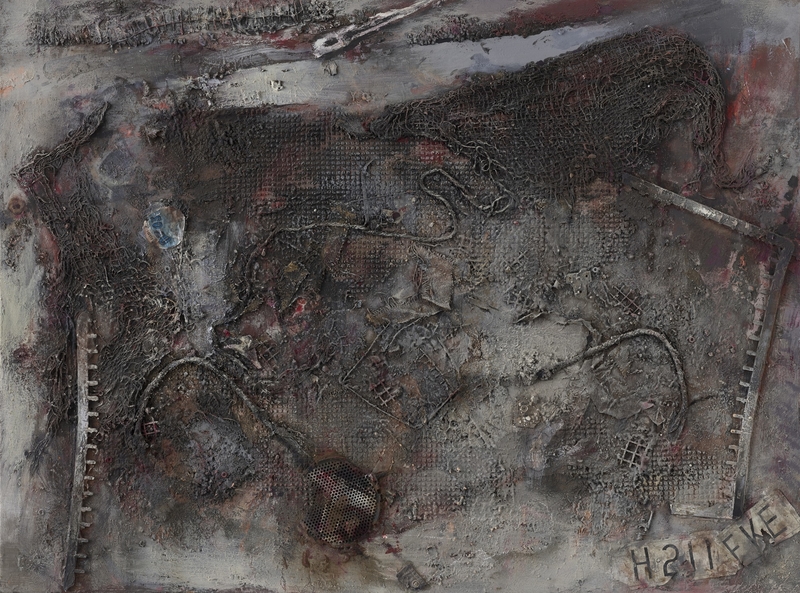

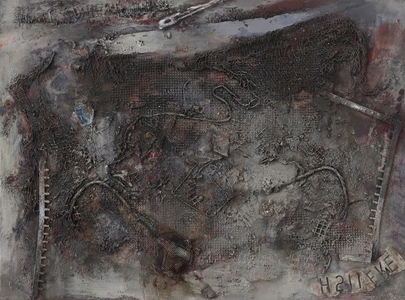

Over the years he has applied it straight from the tube like oil paint, mixed it with other materials to build up sculptural surfaces that dry relatively quickly, then embedded objects into these surfaces. He has painted directly onto canvas and board without previous preparation, and drawn onto the painted surface with other materials, including pastel and charcoal, to create dynamic multi-media works.

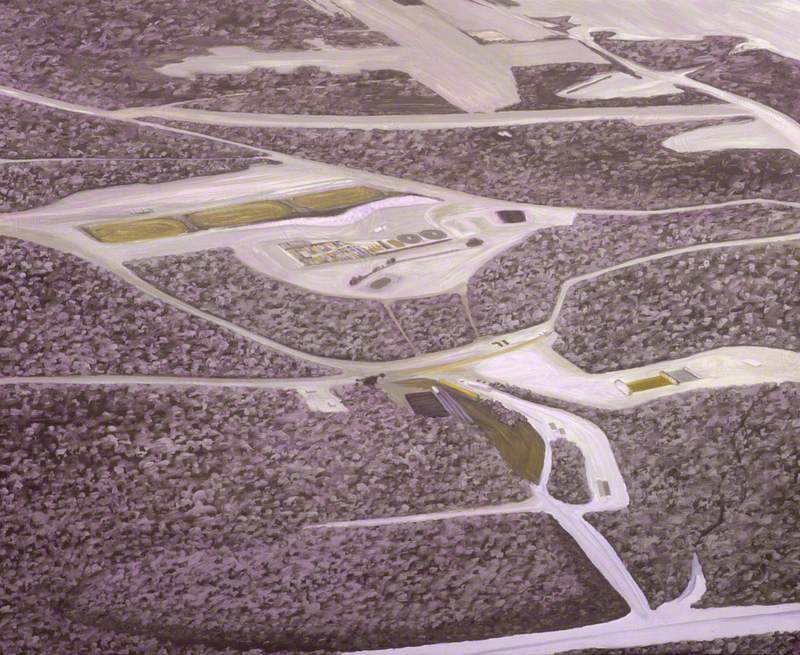

Whishaw's first acrylic paintings resembled large watercolours, with thin washes of colour painted directly onto 'raw' canvas. Whishaw loved the way pigment could impregnate the fibres, softening forms, bringing a new spatial dimension to the work, where it sat on, in and behind the picture surface. These early acrylic landscapes were a haze of amorphous, subtly hued shapes, blending into one another to form a multi-layered cloudscape of pinks, turquoise, blues, purples, yellows and reds devoid of an obvious subject –the interaction of the different layers of colour bringing a different form of visual energy to the earlier oils and figurative paintings.

Yet the source of these paintings was still deeply rooted in Whishaw's memories and experiences, capturing the essence of a field or hill, with a line to suggest the horizon, the curve of a wall or a meandering path, parallel lines to portray a ploughed field, stalks of waving corn, a fence or perhaps sheets of rain, and bands of colour to suggest light and shade moving across the landscape.

The world was reduced to its essential forms: a line, triangle, oval and square rather than picturesque features; things he glimpsed out of the corner of his eye as he drove past or walked through the countryside; simplified objects that momentarily brought the landscape into focus like a vivid memory emerging from the fog of forgetfulness.

Whishaw also experimented with the different effects made possible through collage, adding Tetrion to the paint, turning it into a coloured plaster that seems to cling like mud to the surface of his paintings, giving them a feeling of physical substance and realism. Other substances also found their way into the paintings: cement, ash, sawdust and soil, intriguing us as much with their material surfaces, as the worlds of reality and the abstract imagination they portray.

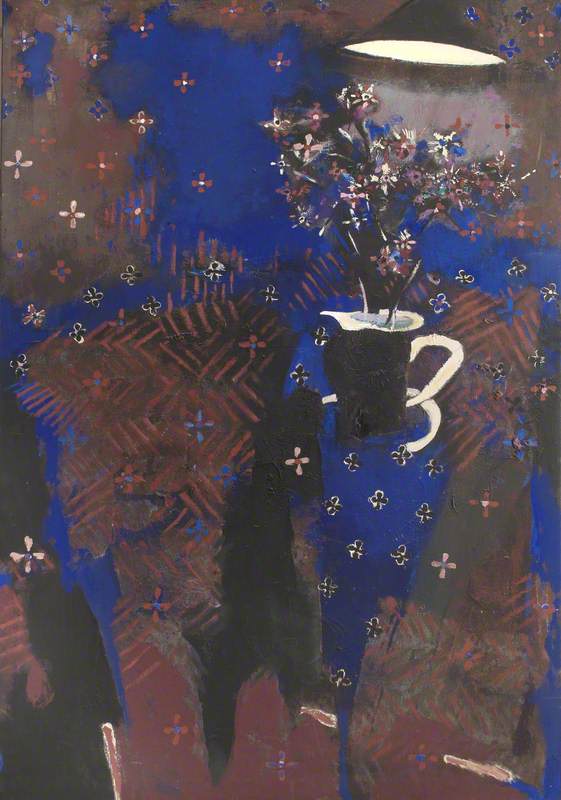

Blue Night Flower Piece

1987–1994

Anthony Whishaw (b.1930)

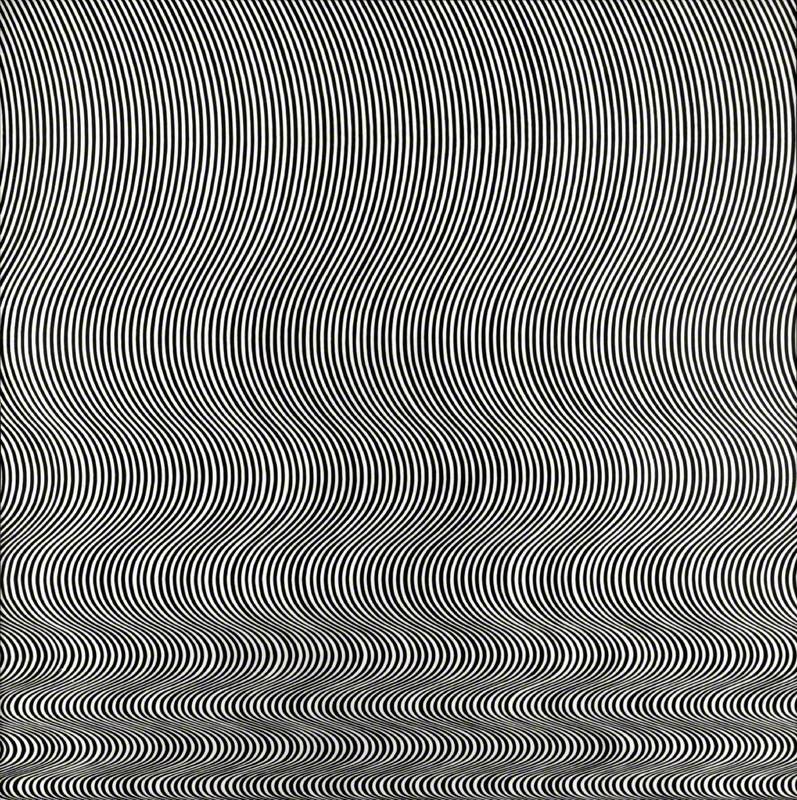

Whishaw's paintings are both playful and full of play – the 'interplay' between surface and depth, solid and void, reflection and reality. His surfaces ripple with positive and negative space, between black lines on white space and white lines on black space. But these lines also create perspectival space, pulling the eye towards vanishing points that carve out three dimensions from the two-dimensional flatness of paper.

Influenced by the multiperspective, interlocking facets of Cubism, Whishaw created a number of interior spaces using rows of parallel black lines to create a series of interlocking flat planes that pull the eye into the depths of the drawing, first this way and then that, trapping us in a house of mirrors of improbable angles. But while these structures initially appear solid, they quickly turn into a tumbling house of cards.

Most of Whishaw's interiors are not so structured, however. Instead of using lines to delineate space and form, he uses colour, creating subtle tonal shifts that allow edges to dissolve, walls to appear and disappear and distances to collapse. In these intangible spaces, trees grow indoors and the sea washes in. These are the incomplete, impossible locations we know from our memories and dreams, where space and time dissolve and internal logic is suspended. We wander through them, feeling the ground fall away beneath our feet, holding on to familiar forms only to find their hard edges disintegrate before our eyes.

Whishaw often looks with a mischievous eye, noticing the unexpected connections between unrelated things. A bath tap can become a dancing figure, 'tap dancing.' He finds a crowd in a whirlwind of tangled lines or interlocking shapes whilst dissolving the human body into a series of simple black strokes of the pen. He turns the curves of a woman into a vase of flowers and a blizzard of light and shadow into a cat. Whishaw's drawings open up windows into other worlds, the result of a process that slowly reveals, which doesn't fix forms or offer answers but opens up the possibility of multiple ways of seeing.

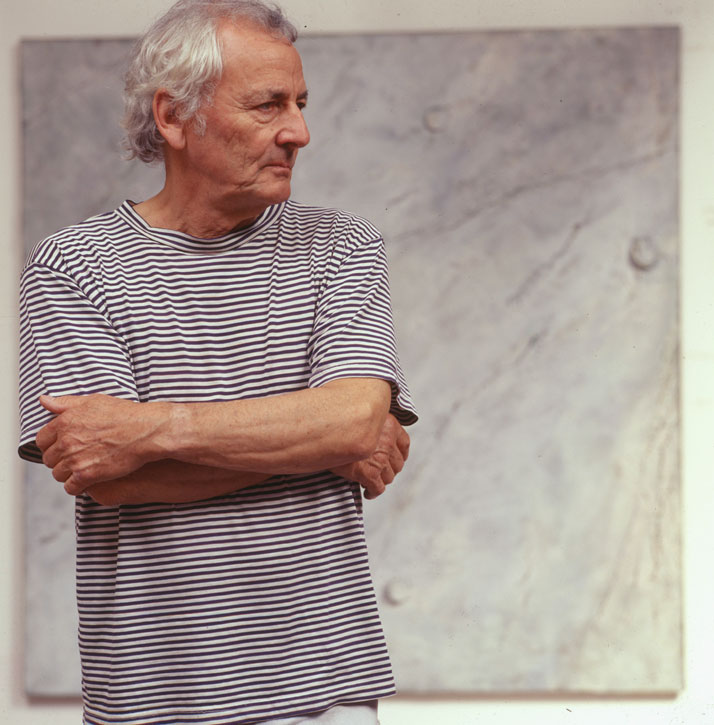

Anthony Whishaw

These multiple ways of seeing are particularly evident in the series of paintings Whishaw has based on Velázquez's painting, Las Meninas (1656). He is drawn to its multiple viewpoints, with the viewer placed in the position of the king and queen who are being painted by Velázquez, who in turn stands facing us along with members of the royal family and court. The image of the watcher being watched is one that intrigues him, as we look at the artist who is looking at us, who in turn is being looked at by a mysterious figure in a distant open doorway, next to a mirror in which the royal couple being painted can be seen looking at themselves.

As well as splatters or large swathes or ribbons of colour, Whishaw often shows us the world as lines, and reveals the possible worlds that exist in a line. Looking at the world through the marks he makes, he finds humour and inspiration in the overlooked, from the idea of the blind leading the blind to the sight of a car with the number plate H211 FKE burning in a Tesco supermarket car park.

As he walked into his ACME studio in Bethnal Green one day, Whishaw became transfixed by the shifting patterns animating a puddle of water by the entrance. He quickly drew them in ink, creating a bold black and white drawing of the positive and negative shapes from memory. He then photocopied this original, enlarging and reducing it, playing with scale and focusing on particular areas, before cutting and tearing up these sheets into smaller fragments.

He has frequently used this original drawing and its photocopied variants to create intricate collages of seascapes, streams and lily ponds. Painting over areas of the collage, or placing scraps of enlarged drawing next to their reduced counterpart, has allowed Whishaw to create mesmerising portraits of water surfaces, with pools of deep calm and emptiness disturbed by patches of wind rippled energy. Turning the photocopied drawing 90 degrees instantly transforms the image.

Anthony Whishaw in 2019

Now standing vertically, the abstract black and white pattern becomes a deeply etched tree trunk fringing a riverbank or pond. A sense of ambiguity and uncertainty defines these images. They play with scale and reality, teasing the borders of micro and macro until we are no longer certain of whether we are engaging with the world in intense close-up or distant disinterest. And ultimately, it is this visual ambiguity and constant playfulness, which are the defining characteristics of Whishaw as a painter.

Richard Davey, author of Anthony Whishaw: Works on Paper

Anthony Whishaw's work can currently be seen in a number of exhibitions, including:

The 'Summer Exhibition' at the Royal Academy of Arts

'From Tonbridge to Tate' at The Old Big School, Tonbridge School, Tonbridge, from 19th September until 13th November 2021

'Through the Eyes of Anthony Whishaw', Fine Art Society, 25 Carnaby Street, London, from 4th October until 5th November 2021