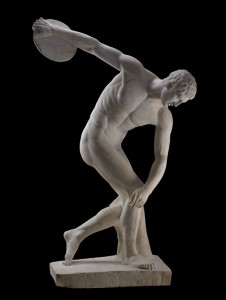

One can find Perseus, one of Greek mythology's most famous heroes, intertwined in the narratives of two iconic women. Somehow, his story takes centre stage. The overlaps take place within a short period. He takes drastically alternate actions towards the women by destroying one but saving the other from destruction.

Both women are ultimately innocent, but as ever, context, timing and perspective are the elements that mark the difference. Medusa was decapitated after a long tale wrapped up in abuse, shame and punishment. Andromeda was 'volunteered' for sacrifice to Cetus, a peckish sea monster, through no fault of her own.

The similarities between the two are startling. In each one's case, her reputed beauty leads to her downfall. The punishment for possession of this most precious gift, aside from objectification, is the ugly fate of eat or be eaten. Another similarity they share is in the ways their stories have been told throughout history. Medusa was most beneficial to the canon towards the end of her life, post-downfall and conveniently nasty. Andromeda's lot is more subtle, but the recent research that points to this altered narrative indicates that she, too, was a tool that offset a beloved hero's admirable qualities.

Andromeda was the daughter of prideful parents, Queen Cassiopeia and King Cepheus, who angered the gods by boasting that she was more beautiful than the best among them. The gods initially wanted the entire dynasty to perish but settled for the daughter's sacrifice to a giant sea monster. The royal family obliged by tying Andromeda on the rocky shores of the stormy sea, ready to be devoured.

Her beauty captivated Perseus, who asks for Andromeda's hand in marriage in exchange for slaying the monster. In literature, she was a gorgeous Ethiopian princess. Ethiopia literally means 'burnt faced' in Ancient Greek, which gives us a clue as to her appearance, as does the fact that she happened to be from the Nubian Kingdom of Kush.

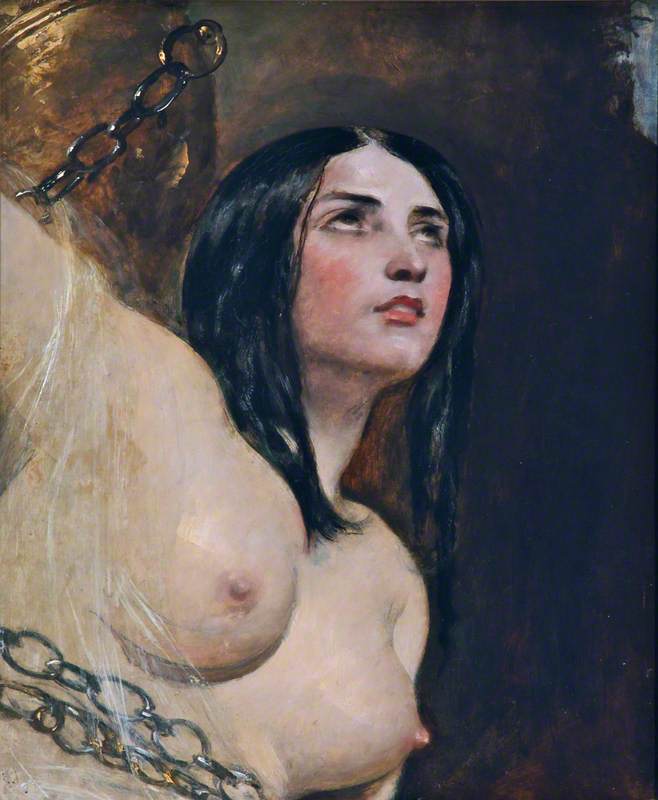

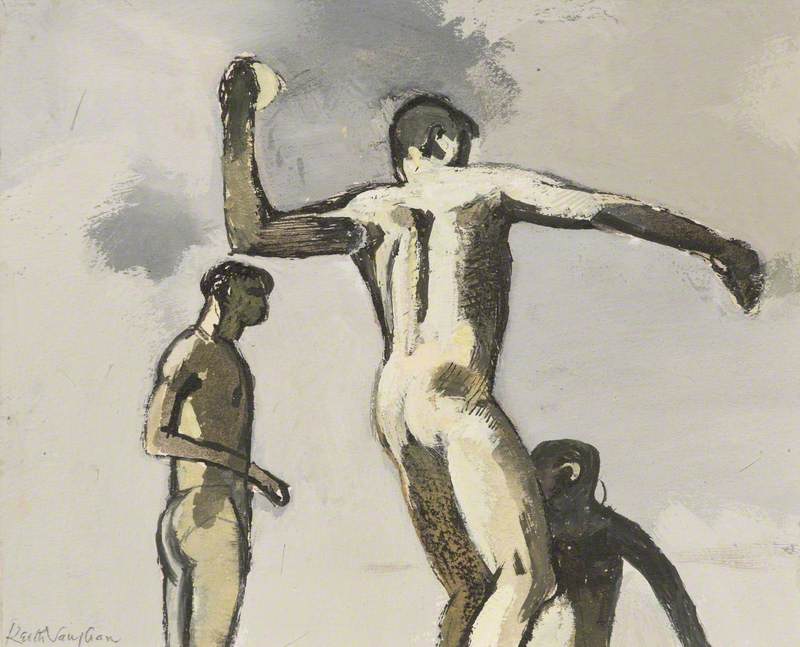

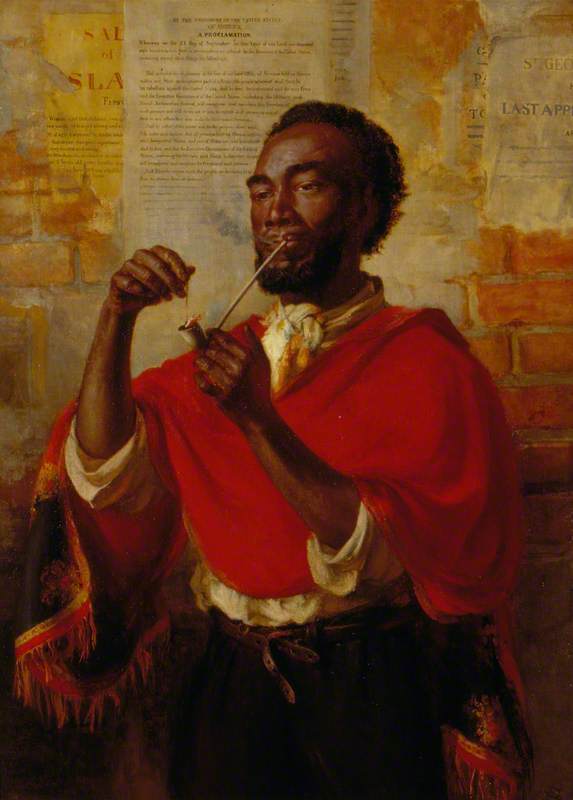

Perseus and Andromeda

(after Guido Reni) 1723–1745

Jeremiah Davison (c.1695–1745)

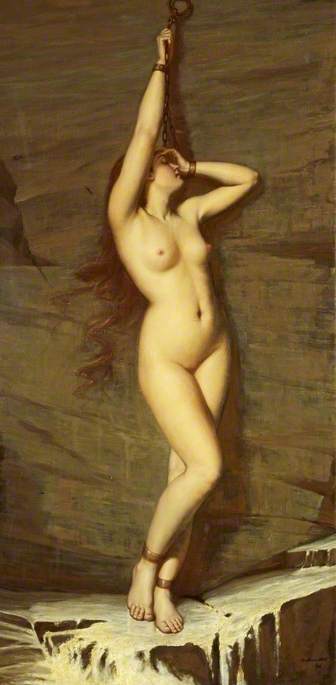

Yet, the way she has been (and continues to be) portrayed is inconsistent with this description. Shown as fair-skinned and distinctly European, Andromeda is still beautiful. In fact, it seems her purported whiteness is the reason for this outstanding beauty – location be dashed. Her beauty, an allure that made Perseus park Pegasus and rescue her from a terrible sea monster, is the crux of her legend.

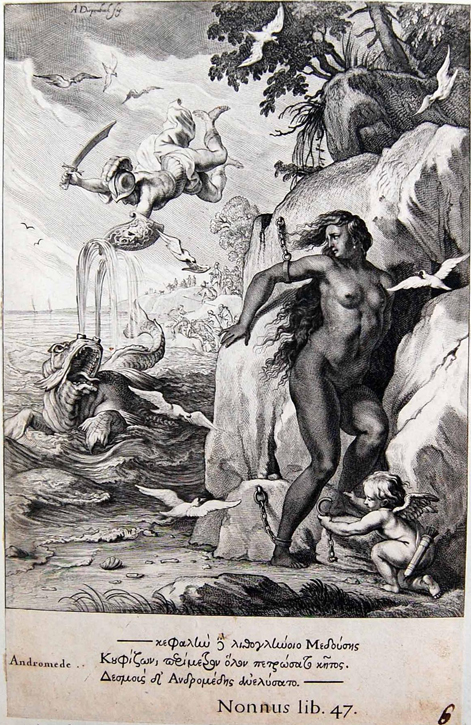

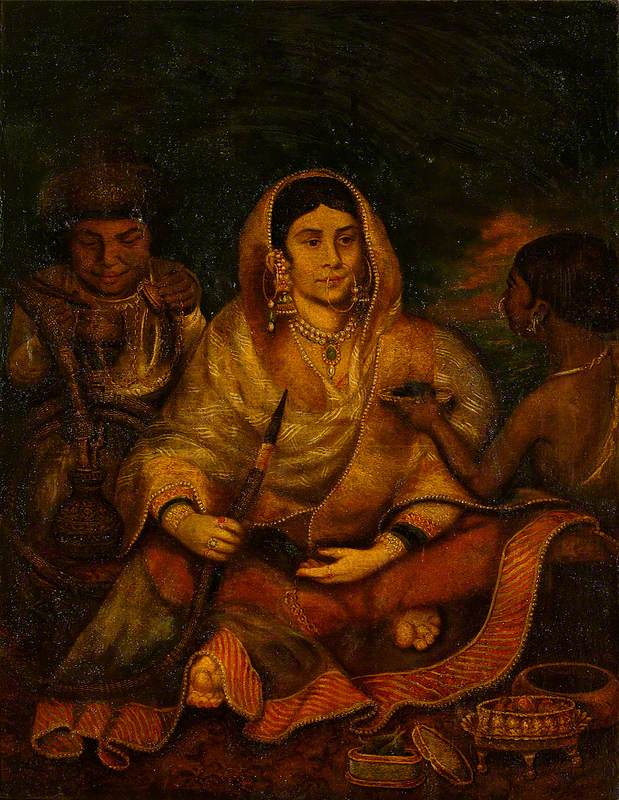

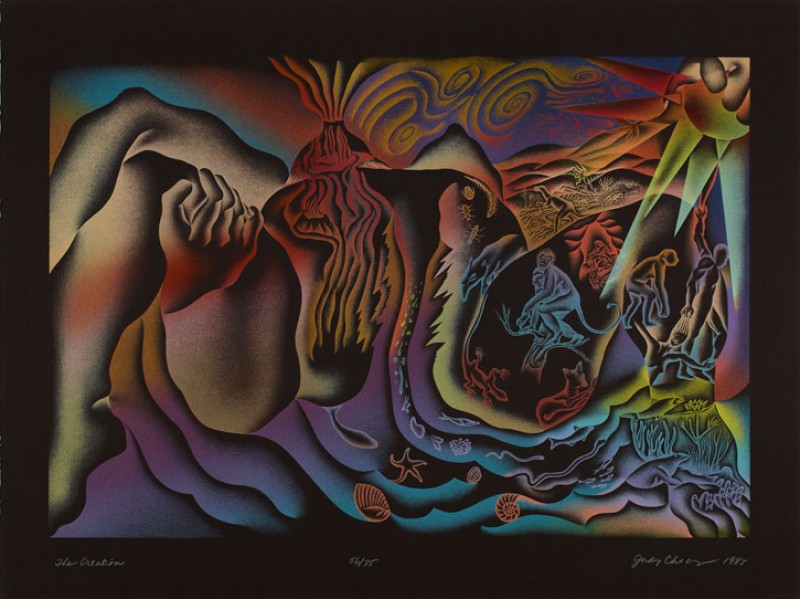

She was described as the most beautiful woman in the world, tawny hue and all, but only a very small number of artworks depict her as dark-skinned, such as this engraving after Abraham van Diepenbeeck.

Even this version of Andromeda shows her with European features.

The Renaissance artists who popularised her image chose not to depict her shade because it presented too much of a problem. It begs the question, had she been described as ordinary, would Andromeda have been portrayed as described? Is her ethnic erasure the result of prejudice or mere ignorance?

Either way, it has left a legacy that is hard to shake. Just ask Hollywood. Why and how did the narrative change? Let's examine why the ancient Greeks – and then the Romans – chose to interpret Andromeda's legend as they did. And let's see why the fact that artists depicted her as they did makes a little more sense, given the context.

Ancient Ethiopia (sometimes spelt Aethiopia) was not the place we think of today – the modern country was known in English as Abyssinia until the 1940s. A story for another time, perhaps. 'Ethiopia' was more of a standard term used by the Greeks to refer to the appearance of the people from the Kingdom of Kush and the surrounding area. Kush was a part of ancient Nubia located in what is now known as the northern part of Sudan.

Assuming the word 'Ethiopia' is derived from Greek for 'burnt face' (which is not accepted by all Ethiopians today – some believe it to be from the name Itiyopp'is, son of the Biblical Cush), it could today be considered a racial slur, and perhaps is the most telling aspect of the Andromeda identity crisis. The lands of ancient Nubia were trading centres, so it's not surprising that the ancient Greeks would have been familiar with it. Likely, these writers would have been aware of the multiple dynastic rulers that the area produced over time. Perhaps the stories of these rulers fed the imaginations of the early recorders of Greek mythology, who were undoubtedly intrigued by the mystery of the exotic south.

Ancient writers, all of whom preceded the artists who interpreted Andromeda as they saw fit, asserted that the princess was black. Petrarch, writing in the fourteenth century, described Andromeda as the 'virgine bruna', and was not alone in commenting on the colour of her skin. He wrote that he wanted to know 'how it was in Ethiopia the dark-skinned maiden Andromeda attracted him [Perseus] with her fine eyes and hair.'

The ancient Roman poet Ovid wrote of Andromeda's hue centuries before Petrarch, who would have come across the following description when he translated Ovid's work: 'I may be short, but I have a name that resounds worldwide and this I take as my measure. And though I'm not pure white, Cepheus's dark Andromeda charmed Perseus with her native colour. White doves often choose mates of different hue and the parrot loves the black turtle dove.'

Ovid also wrote advice to women on how to be more seductive, and his advice to dark-skinned women was based on Andromeda's legend: 'White suits dark girls; you looked so attractive in white Andromeda, when you walked upon Seriphos.'

Even if the works of art depicted a fair-skinned Andromeda due to confusion about the location of Ethiopia, there was still no reason to confuse her ethnicity as being white. Some ancient writers thought of 'Ethiopia' as potentially Indian, or even Phoenician, and Pliny's writings, in particular, have been interpreted to signify that Andromeda was from Joppa, in Palestine. This may have been for the sake of an appeal to the people of Joppa to help the Romans militarily, and so they incorporated the location in a most flattering legend. In any case, Andromeda has not been depicted as being brown – as in Indian or Middle Eastern – either.

Besides, Renaissance (and later) artists were not uneducated. Indeed, books from ancient philosophers not only served as a source of education for them but one of entertainment, too. There is little doubt in the minds of contemporary historians, such as Elizabeth McGrath, that artists were aware of the original descriptions outlined above and many more besides. In fact, these descriptions were helpful in their ambiguity.

Some writers had written her as beautiful despite being dark-skinned – like her beauty surpassed the 'problem' of her hue. Others noted that she was ugly, not beautiful, because she was black, but Perseus loved her anyway. Others still completely bypassed her ethnicity but stated that she was unusually white compared to her fellow countrymen – hence the loveliness.

Suppose the writings showed this ambiguity, this reluctance to accept a single identifying marker in a heroine. What motivations would the artists have had to be accurate, as they later represented the scene of her rescue by the brave white hero? This question is particularly pertinent when one measured when these visual artworks were created.

From the early Renaissance to the Enlightenment, Europe went through significant economic and cultural changes. The landscape of fierce competition for progress was how the depictions of Andromeda were created and received. Given the usefulness of the transatlantic slave trade to Europeans during these centuries, a black and beautiful Andromeda would not have gone down well. That's not to say all of these artists signed an agreement to uphold the ideals of their time – perhaps they genuinely could not see the two identity markers – beauty and blackness – as making sense together.

So, why was Andromeda portrayed as white when her legend points to African origins? Put simply, because there was a more powerful narrative to consider. Vastly concerned with maintaining the status quo, this narrative looked at human beings through a hierarchical lens. Since beauty has always been a high commodity, it could not have been afforded to a deliberately oppressed class. Not to mention that the visual of a white man rescuing a chained up black woman would have been too much of a trigger and perhaps an inconvenient catalyst for the change that eventually ensued.

Patricia Yaker Ekall, journalist

Further reading

Sophia Galer, 'How Black women were whitewashed by art', BBC Culture, 2019

Michael Ohajuru, The Image of the Black in London Galleries

Henry Louis Gates Jr, 'Was Andromeda Black?', The Root, 2014

Elizabeth McGrath, 'The Black Andromeda' in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 55, 1992

Perseus frees Andromeda by Piero di Cosimo in the Uffizi Galleries, Florence