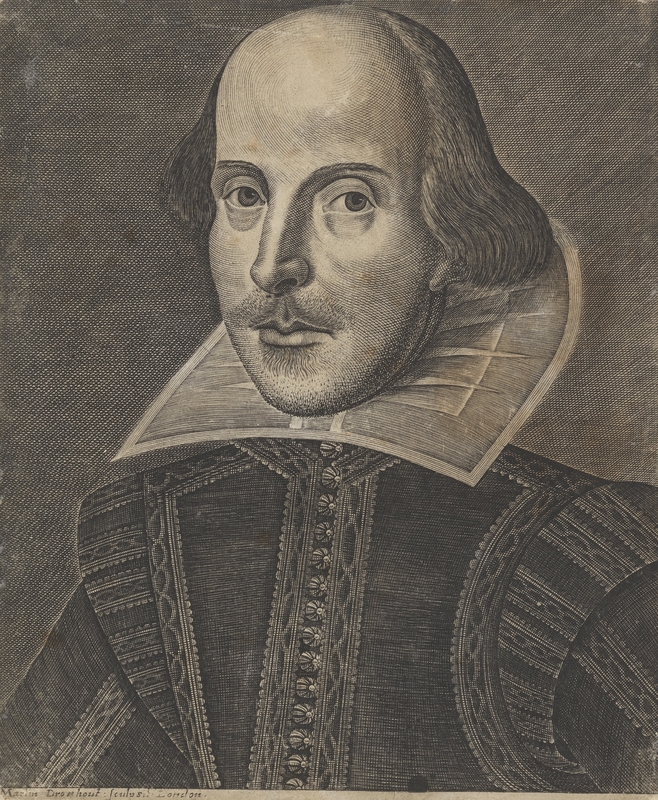

Until 2002, the Cobbe portrait of Henry Wriothesley from around 1590–1593 was thought to depict a woman. An overlooked work in the Cobbe Collection at Hatchlands, its label, 'Lady Norton, daughter of the Bishop of Winton', went unchallenged until a visitor noticed its striking resemblance to a different sitter. This was Henry Wriothesley (1573–1624), 3rd Earl of Southampton, a courtier best known today as William Shakespeare's early patron and the rumoured inspiration behind the 'fair youth' and the 'master-mistress' of his sonnets.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Henry Wriothesley (1573–1624), 3rd Earl of Southampton 1590–1593

John de Critz the elder (1551/1552–1642) (attributed to)

National Trust, HatchlandsThe portrait was cleaned, removing centuries of yellowing varnish to reveal Wriothesley's tumbling curls, sharp nose, arched brows and single earring. While the sitter's identity was confirmed, however, the portrait's androgyny remained.

In the Cobbe portrait, Wriothesley cuts a dramatically different figure from the heavily robed and bearded male sitters of many Henrician and Elizabethan portraits. This genre is exemplified by the decorous portrait of Wriothesley's guardian, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, depicted in the 1590s with dark yet opulent robes and holding a white rod – a symbol of his office as Lord High Treasurer.

With his unusually smooth chin, pale complexion and long hair, Wriothesley presents an unconventional image of early modern masculinity. In dialogue with his famed literary patronage, the wider culture of the court and the tumultuous events of his life, his many portraits in UK collections provide an insight into how this astute and ambitious sitter crafted his self-presentation.

Typically designed to be hung in homes or exchanged as gifts, these portraits used a range of devices – from fashion to gendered tropes – to aid Wriothesley's causes on the early modern social and political stage.

The Cobbe portrait, attributed to the Netherlandish court painter John de Critz (1551–1642), is the earliest identified depiction of Wriothesley. He is shown pressing his long hair to his heart with one hand in a gesture that mirrors those of love-sick or melancholy sitters in Elizabethan portraits, such as this depiction of Sir Henry Slingsby.

The Cobbe portrait, however, is not just a conventional depiction of melancholy. The painter emphasises Wriothesley's pale skin, almost glowing in contrast with his black doublet and the dark background. His complexion is warmed only by his red cheeks and lips.

This creates a palette of reds, whites and blacks that was one of the hallmarks of Tudor poetic descriptions of women, as writers endlessly praised their white skin and red lips – a formula made popular by the Italian poet Petrarch.

These were not just poetic but visual tropes, almost ubiquitous across women's portraits of this era, exemplified by a painting of a courtier, possibly Helena Sankenborg, from around 1567–1569, and those of Elizabeth I. This palette suggests conventions more commonly used to depict women than men.

This effect is heightened by Wriothesley's long hair and earring. These styles were worn by certain fashionable Elizabethan male courtiers. Walter Raleigh, for example, wears a prominent pearl earring in his 1588 portrait.

Yet for critics, such details could make their wearers threateningly androgynous. As these trends persisted into the seventeenth century, the Puritan writer William Prynne criticised how long hair made men 'Womanish'. In Elizabethan poetry, however, men with long hair, a pale complexion and a smooth chin were sometimes praised explicitly for their androgynous beauty.

This rhetoric drew on classical poetry, and especially Ovid, the transgressive Roman writer experiencing a revival in the court at its peak in the 1590s. Epitomising these descriptions, the writer Christopher Marlowe's Hero and Leander (1598), highlights Leander’s 'dangling tresses that were never shorne', 'orient cheekes and lippes', with the effect that 'some swore he was a maid in mans attire,/ For in his lookes were all that men desire'. In 1593, Shakespeare even dedicated the poem Venus and Adonis to Wriothesley, likely intending to flatter him through implied comparison with the beautiful, ephebic protagonist Adonis.

These parallels raise questions about Wriothesley's sexuality. While he married Elizabeth Vernon in 1598, rumours of bisexuality surrounded him in his lifetime – and ever since. At a time when homosexuality was illegal and gay relationships largely unfolded in secret, it is impossible to reconstruct this possible aspect of his life. A portrait that spoke directly to forbidden desires would have been too risky to make.

Image credit: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Portrait miniature of Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton

1594, watercolour by Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619)

Like the miniature of Wriothesely from this era, the Cobbe portrait remains ambiguous, presenting Wriothesley as a similarly androgynous and fashionably transgressive figure to those in Elizabethan Ovidian poems. Linked to recent events in Wriothesley's life, this presentation may speak to his refusal to marry his guardian's choice of bride in 1590, incurring a £5,000 fine. The Cobbe portrait could present the sitter's spin on these events. By presenting in the guise of the beautiful yet unattainable young men from classical poems, Wriothesley projected a rebellious, literary and attractive persona.

Image credit: public domain (source: Wikimedia commons)

Henry Wriothesley (1573–1624), 3rd Earl of Southampton

1603, oil on canvas attributed to John de Critz (1551–1642)

Rebelliousness continues to be a theme in Wriothesley's later portraits. A painting from before 1603, also attributed to John de Critz, depicts him imprisoned in the Tower of London for his part in the Essex rebellion against Elizabeth I, for which he had received a lifelong sentence. A copy also survives from the nineteenth century. Wearing similar clothes to the Cobbe portrait, his hand is once again silhouetted against his dark doublet, this time drawing attention to his arm in a sling, perhaps an injury sustained in the rebellion.

Image credit: Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

John L. Riley (active 19th C)

Shakespeare Birthplace TrustWhile legend has it that the cat in this painting was his pet 'Trixie', this animal was understood as an emblem of captivity in early modern art due to its perceived independence. The bars on the window add a further allusion to imprisonment. In the sixteenth-century version, the meaning of these symbols is made explicit by the depiction of the Tower of London in the top-right corner, and the Latin motto, 'in vinculis invictus' ('in chains, unconquered'). Responding to his imprisonment, this portrait and its copy reframe Wriotheseley's anti-authoritarian acts as examples of his constancy in adversity.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Henry Wriothesley (1573–1624), 3rd Earl of Southampton

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636) (and studio)

National Trust, Dyrham ParkWhen James I came to the throne in 1603, he set Wriothesley free. This moment marked a shift in his self-presentation, towards greater military themes and echoes of the monarch's own appearance. In one portrait, attributed to the studio of Marcus Gheeraerts, an older Wriothesley stands with one hand on his hip, the other resting on a table, beside a plumed helmet. His hand hovers by his sword, as if ready for action, and he wears the Order of the Garter around his neck, a marker of court status that he was awarded in 1603.

With his shorter hair and beard, this portrait shows a strong resemblance to portraits of James I, suggesting Wriothesley was publicly affirming his loyalty.

While his clothes remain flamboyant, his beard, symbols of office and weapons lend him a conventionally masculine and military presence. This is even more apparent in the portraits of Wriothesley in full plate armour.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton c.1618 (?)

Daniel Mytens (c.1590–1647) (after)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonThese changes both reflected and commended Wriothesley for his new advancement in court and growing military role, for example, fighting on the Protestant side of the wars of religion in Germany in 1614 and 1617.

These portraits demonstrate Wriothesley's adept manipulation of fashion, gender and symbolism. They not only map his extraordinary life but reveal how he controlled his image to his advantage.

Image credit: The Harley Foundation, Portland Collection

Henry Wriothesley (1573–1624), 3rd Earl of Southampton 1605

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636) (style of)

The Harley FoundationMore than simply capturing a sitter's appearance, in the cut-throat world of the Tudor and Jacobean court, where looks could make a man, portraits like these could play a vital role in a courtier's advancement.

Alice Blow, art researcher and writer

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

George Akrigg, Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton, Hamish Hamilton, 1968

Tarnya Cooper (ed.), Searching for Shakespeare, National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2006

Cora Fox, Ovid and the Politics of Emotion in Elizabethan England, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009

Raphael Lyne, Ovid's Changing Worlds: English Metamorphoses 1567–1632, Oxford University Press, 2001

Christopher Marlowe, The Complete Works of Christopher Marlowe, I: All Ovids Elegies, Lucans First Booke, Dido Queene of Carthage, Hero and Leander, Roma Gill (ed.), Oxford University Press, 1986

Alan Riding, 'Not Just Another Pretty Face', New York Times, 6 May 2002

A. L. Rowse, Shakespeare's Southampton: Patron of Virginia, Macmillan, 1965

William Shakespeare, The Sonnets, William Burto (ed.), Penguin, 1964

William Shakespeare, Shakespeare's Poems: Venus and Adonis, The Rape of Lucrece and the Shorter Poems, Katherine Duncan-Jones and H.R. Woudhuysen (eds.), Thompson Learning, 2007