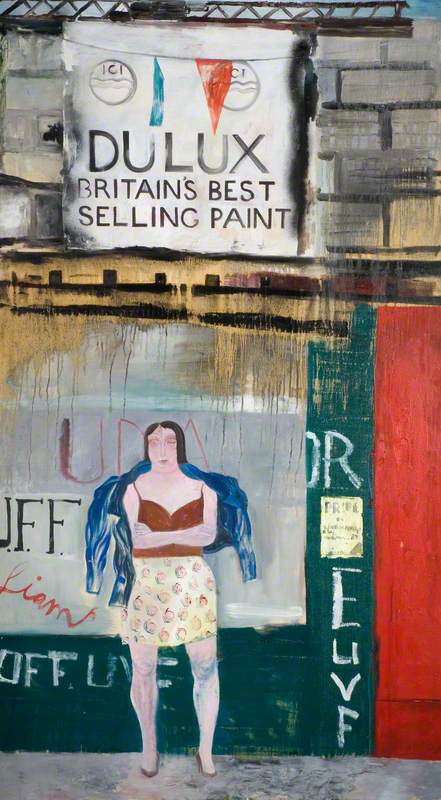

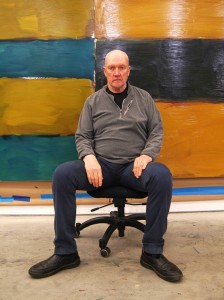

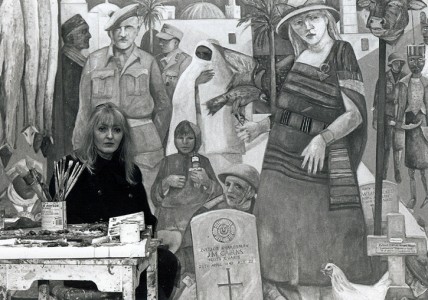

Artist Jock McFadyen RA (b.1950) first made a name for himself by painting London's East End during the 1980s. These images are filled with contemporary figures on street corners, leaning against walls covered in graffiti. But, over time, the people disappeared from his paintings. Today, he portrays empty, evocative landscapes, which resonate with our experiences of isolation during the Covid-19 lockdown.

So, where did all the people go?

Continue reading to find out, in this exclusive interview undertaken by email between Ruth Millington and Jock McFadyen during lockdown.

Ruth Millington: Let's start with your art education. You studied at Chelsea School of Art. What was that like?

Jock MacFadyen: Chelsea in the early 1970s was totally contemporary, it was a pretty vibrant art school and many students went on to succeed in becoming artists: Helen Chadwick, Anish Kapoor and Christopher Le Brun are just some of the people I overlapped with. Visiting lecturers included Claes Oldenburg, Tom Stoppard, Quentin Crisp, Ernst Gombrich and Eduardo Paolozzi.

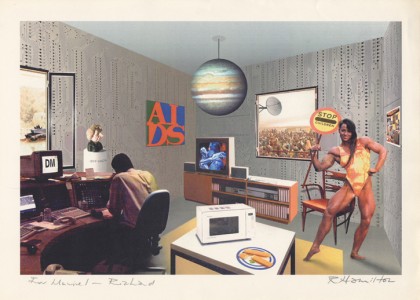

Pop Art was still in evidence and photorealism was hovering in the wings and there was the backdrop of minimalism, conceptualism, video, installation, land art, mail art, structuralist film and performance. I specialised in painting but also made films with Anne Rees-Mogg the film tutor, and film has been an influence on my painting.

Ruth: During the 1980s, you were painting pictures of London, especially the scruffier parts of the city. Why were you drawn to these locations?

Jock: After art school, there was a huge diaspora of young artists to the East End. This started in the 1960s with Bert Irvin and Bridget Riley decamping to St Katharine Docks. Warehouse spaces became studios: my first studio was a bit of floor in Butler's Wharf which was home to about 200 artists, including Andrew Logan, Anne Bean, Richard Wilson and Derek Jarman.

My work changed after I was Artist-in-Residence at The National Gallery in 1981. Before that, my pictures had been schematic and self-referential, but after emerging from that residency my focus was to make art that describes the world. So where do you start with that? Well, you open your front door which happens to look out onto a scruffy part of the city.

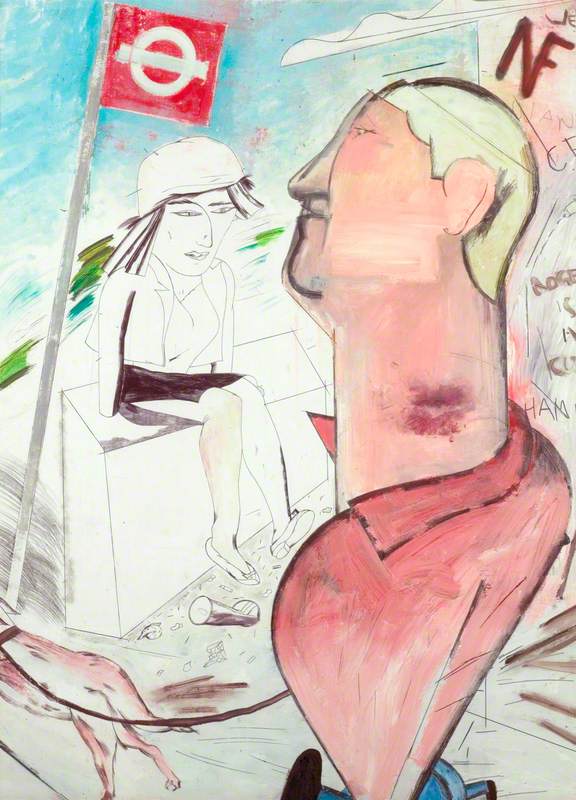

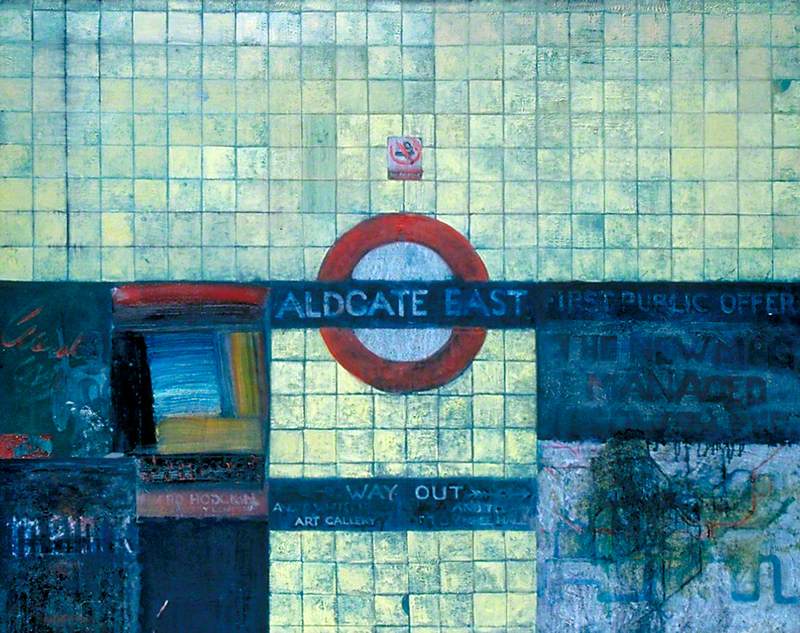

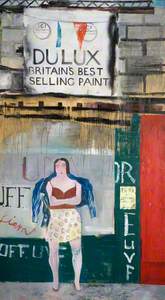

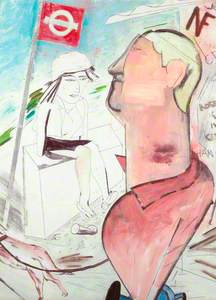

Ruth: In your paintings of the urban landscape, there's a focus on graffiti, signs, typography and cultural references. For example, you include a poster for a Howard Hodgkin show in the work Aldgate East 1. What is your interest in these?

Jock: In London there are little voices here and there straining to be heard, whether it’s the loner with a spray can or a highly decorated establishment painter or, if you prefer, a highly trained professional street artist or a deceased decorative painter.

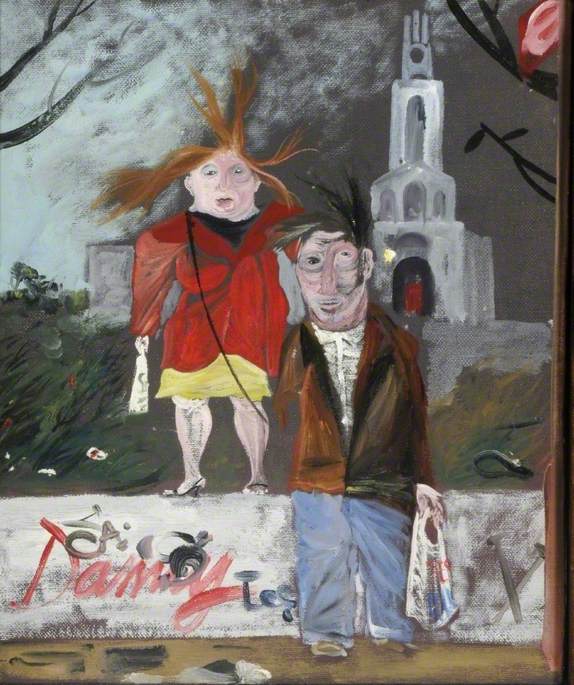

Ruth: And these paintings are filled with figures. Who were these people?

Jock: The figures were all based on people I saw in the street which I then tried to reconstruct back in my studio, furiously doing visual memorising and doodling and sometimes returning like a private detective to photograph them – Jock McFadyen the stalker.

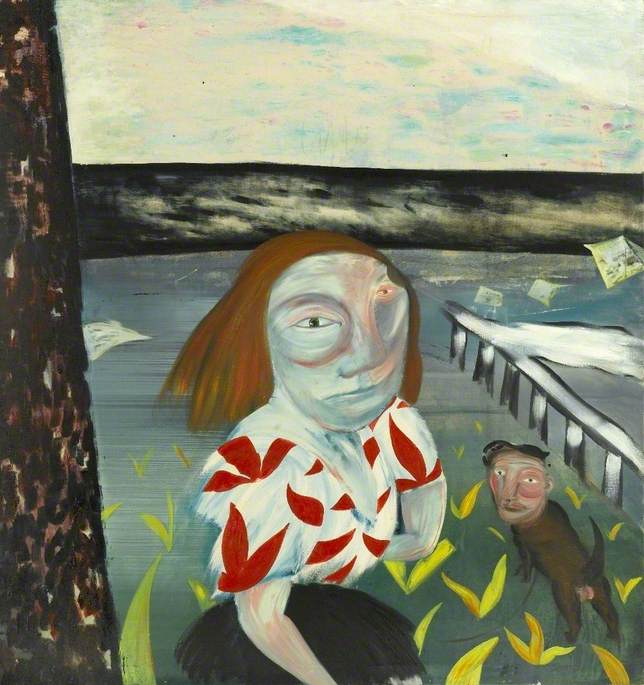

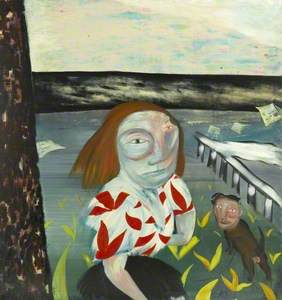

Ruth: Then, over time, these figures disappeared. Was this a conscious decision? Or more gradual?

Jock: It dawned on me in the early 1990s that the struggle in my pictures was in the structure, the background was the main thing and the figures were the spontaneous bit, or at least the quickly realised bit.

The figures had been getting smaller and in 1992 I designed a ballet for Kenneth MacMillan at the Royal Opera House, and it involved a huge amount of urban landscape. The set included three cars, buildings, scaffolding and loads of graffiti, with the newly built Canary Wharf tower twinkling in the background. But no figures were needed because there were real people, the dancers.

So, when I was back in my studio it was natural to continue with pictures without figures and it was a revelation. Painting the figure is emotionally and psychologically different to painting the landscape. The important shift for me was that with a landscape the viewer is levered into looking at the paint and the texture, much more like abstraction. With figuration of all kinds, the figure leapfrogs over those considerations to grab attention for itself. The paint is much less up for contemplation because the figure is so psychologically charged.

Ruth: Do you seek out places to paint, or do they present themselves to you?

Jock: All landscape painters would claim an obsession with location but Cézanne didn't just paint Mont St Victoire.

There are compelling locations that are unwilling to be painted in a way that makes the paint work and then the picture doesn't succeed. Some would say that a better painter would paint the location anyway and to hell with the result, but both parties have to yield, the painter and the painted. That's why painters move trees and buildings around and tell topographical lies. Lowry is particularly culpable in this and yet his work is treasured for its fidelity to a particular region

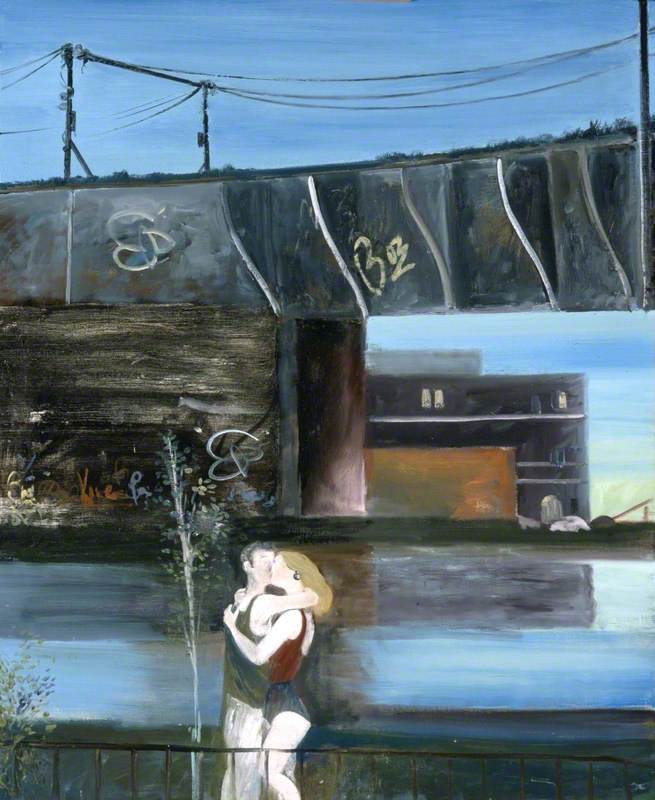

There is also the exciting fact that a subject might be portrayed in different media. For example, the writer Iain Sinclair and I share an obsession with a particular part of London and its outerlands and that landscape might be painted, filmed, photographed, musicalised or written about. If the artist is prepared to be subject-led then formal invention will follow and with a bit of luck, the picture might work.

Ruth: And is it true that you like to find places to paint by riding motorbikes through the city?

Jock: There is a great difference between riding a horse and sitting in a carriage. On a horse or a bike one is in the air, in the elements with ever-present danger and while driving a car one is sitting in an armchair looking at the world through windows while pushing levers and buttons, steering, chatting or listening to music. Riding a bicycle or a motorbike is a wonderful way to penetrate the landscape.

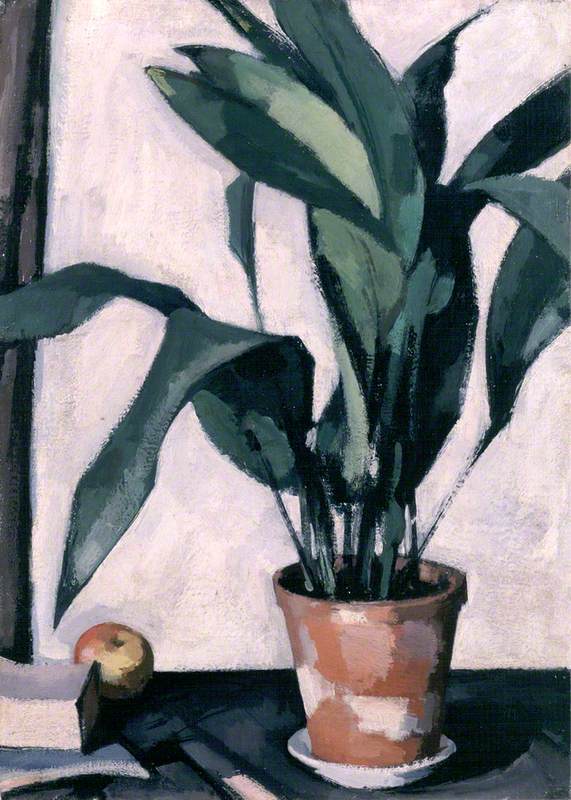

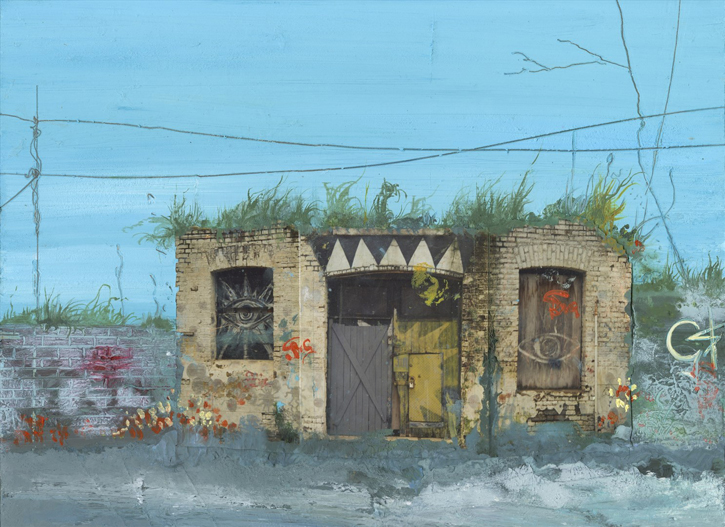

Blackman's Yard

2017 by Jock McFadyen (b.1950)

Ruth: Do you take photos of places before painting them? How does your painting relate to photography?

Jock: I love photography. And I love the energy which occurs when photography and painting collide. When I was a first-year art student I found a bag of photographs which were of road markings. They were instructions for roadmen telling them where to dig and they included hedges, walls and bits of street furniture. I took these to my studio space and pasted them to my pictures and painted around them and felt the frisson of two realities.

I have always used photographs to visually rehearse my large paintings. I used to snap areas of interest and frame up and crop and edit and finally square up on the canvas in order to guesstimate where to put the first bits of paint on the surface.

These days I use a phone like everybody else and have it on a five-minute cut-off with poor definition. It's important to have low quality photographic information because you don't want photography to encroach or make any contribution to colour, depth of field, texture, perspective or anything which is the business of painting.

The frisson created when photos and paint occupy the same pictorial space precedes me. I want to acknowledge the influence of Arnulf Rainer, Ian McKeever and, most famously, Robert Rauschenberg.

Ruth: Do you have other artistic influences? Over time, has this changed?

Jock: It's great being a painter because you know that you are a tiny part of a huge and ancient tradition which yawns before you and will go on as long as there is life. All you can do is reach out to the bits of art history which you identify with. It started with Pop Art for me, but now it's Holbein and Turner.

Ruth: During lockdown, we are all much more aware of our local environments. Have you noticed anything new and has it impacted on your work?

Jock: I have been self-isolating for the last 45 years so no change there.

I have a place in northern France and also a flat in Edinburgh where I divide my time. I only find London bearable if I get away from it on a regular basis and I have never spent such a continuous stretch in London before. I haven't seen anything afresh but the empty streets and quietness were incredible, like 28 Days Later, or a post-nuclear vision.

It actually felt like one of my pictures.

Ruth Millington, art critic and writer