'Ain't I a woman?' asked Sojourner Truth in a famous speech delivered at the 1851 Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. Truth, an activist preacher freed from enslavement, was the only Black woman present at the convention, and many people did not want her to speak. Early feminism was notoriously centred around the rights of white women, particularly in the US, and Truth tackled this head-on: 'ain't I a woman?' she asked repeatedly. Her speech is remembered today as a pivotal moment in Western history and the intersectional fight for women's rights.

This simple question – later adopted by bell hooks as the title of her influential book Ain't I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism (1981) – is the title of a thought-provoking display at Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery, featuring newly commissioned works by artists Adéọlá and Catriona Abuneke.

'ain’t I a woman?' installation view

Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery, 2024

Here African diaspora spirituality meets Merthyr's historic super-rich in a small but powerful display which suggests new possibilities for understanding wealth, womanhood, race and the legacy of Wales' industrial-colonial past. It teases out the human cost of mass industrialisation and introduces an alternative to Western capitalism in the form of the goddess Aje, Yorùbá symbol of trade, prosperity and wealth.

The display is part of Ffoto Cymru: Wales' International Festival of Photography. Ffotogallery invited four female or non-binary artists to create a visual response to archives across Wales, starting with the question 'What You See is What You Get?' The festival encouraged the exploration of stories that dwell on the edges: the invisiblised, marginalised and unsaid.

View this post on Instagram

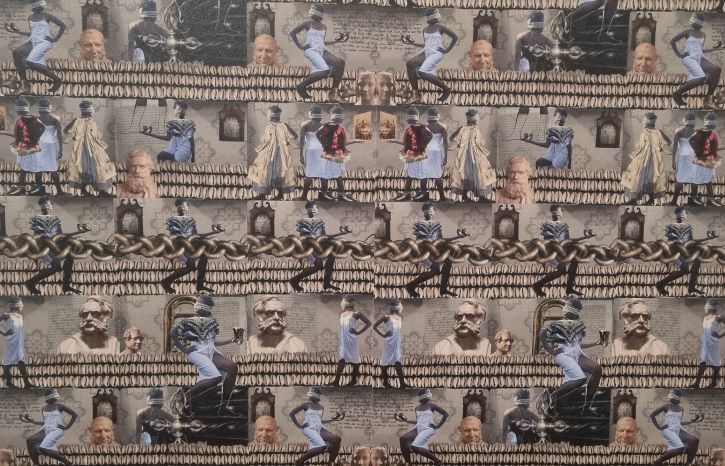

As part of the festival, Adéọlá and Catriona Abuneke were commissioned to create new works in response to items from Cyfarthfa's archive and collections. Their collaborative response includes digitally manipulated photography, video and a bespoke wallpaper design.

There isn't a single, straightforward narrative to the display. Instead the juxtaposition and layering of objects and images opens a space for new and concealed meanings to emerge. Themes explored include workers' rights, suffrage, spirituality, the home as exhibition space, and the wealth – and human cost – of mass industrialisation.

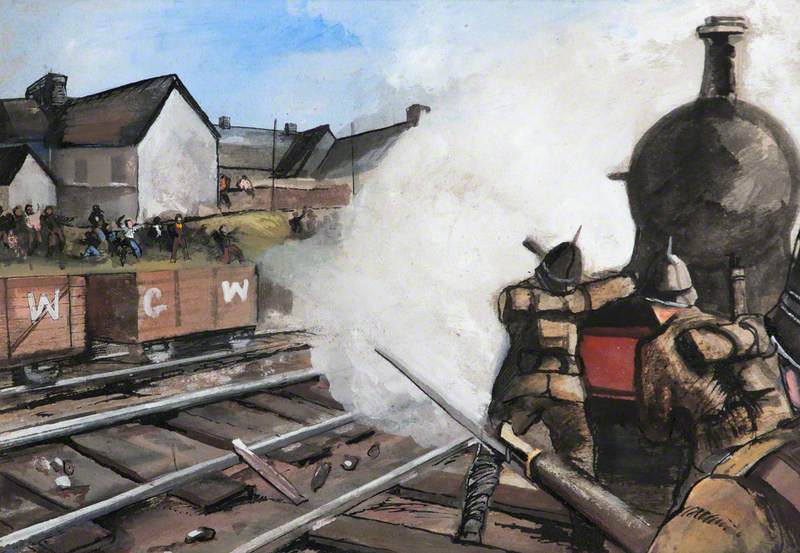

At the start of the nineteenth century, Cyfarthfa Ironworks was the biggest in the world. It brought unprecedented wealth to south Wales, and made Merthyr Tydfil a powerhouse of the industrial revolution. The majority of the wealth was concentrated among a small group of people: Merthyr Tydfil's ironmasters and their families, including the Crawshays. The legacy and impact on the local community was mixed. While some came to see the Castle as a symbol of Merthyr's prosperity and unprecedented opportunities for employment, for others it became a symbol of oppression and extreme wealth inequity.

'ain’t I a woman?' installation view

Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery, 2024

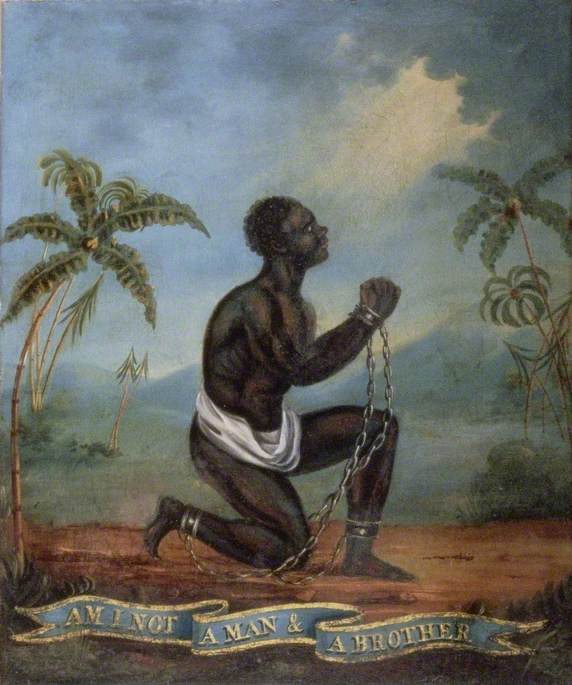

There are global entanglements, too. As Eric Williams explains in Capitalism & Slavery – a book that is subtly referenced in the display – the furnaces at Cyfarthfa were founded in the eighteenth century with an investment by Anthony Bacon, whose wealth came from the profits of colonial trade and the trafficking of enslaved people. The Black bodies present in this display memorialise those who suffered, died or were robbed of their humanity, and whose violent exploitation helped pave the way for Wales's industrial revolution.

Rose Mary Crawshay, who married Cyfarthfa ironmaster Robert Thompson Crawshay, was a celebrated campaigner for women's suffrage, and an advocate for local education, libraries and access to books. But her speech on the 'Female Suffrage Question' at Zoar Chapel, Merthyr on 18th October 1873 reveals that even the most ardent white feminists and socially-conscious campaigners were influenced by prevailing contemporary attitudes to race and colonialist ideas.

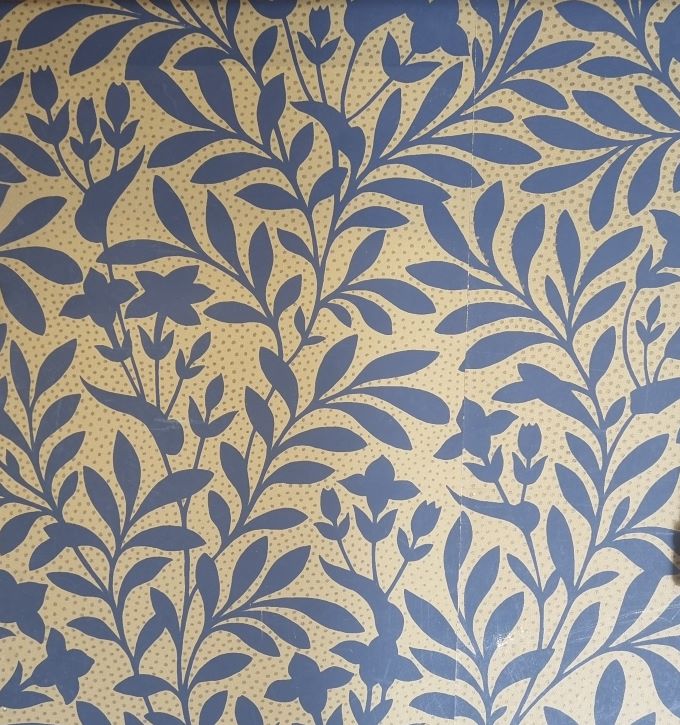

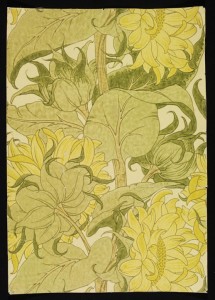

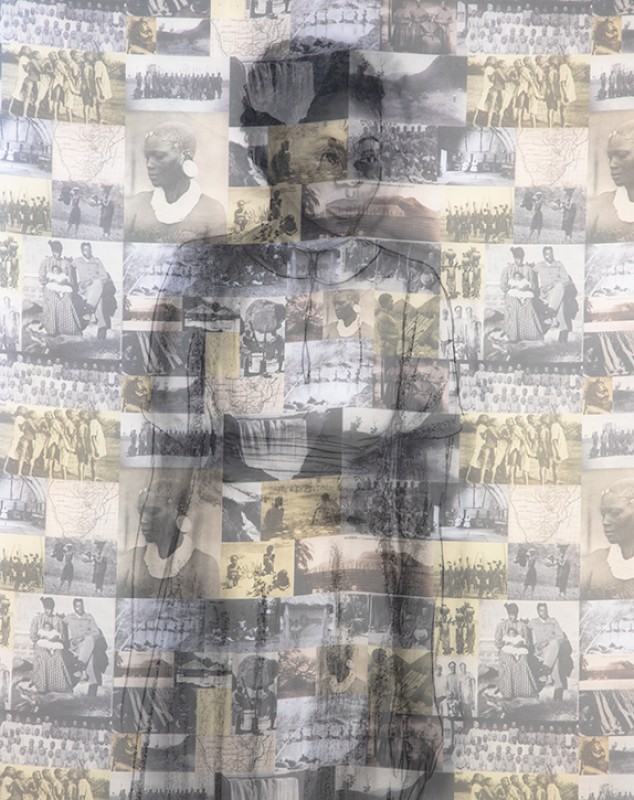

Wallpaper (detail) in a room that was previously the Crawshay office

Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery

Some of Rose Mary's words from her speech are handwritten into a bespoke wallpaper designed for this display. Wallpaper is something that sits on the margins: a bracket to our domestic world, often overlooked. Adéọlá notes how she was inspired in part by seeing the wallpaper in many of Cyfarthfa's rooms - rooms which were previously the Crawshay family's domestic spaces, and are now utilised as an exhibition space. The reframing of wallpaper as artwork invites us to think about domestic furnishings in new ways, blurring the conceptual boundaries between home displays and the exhibition space.

ain't I a woman?

2024 (detail), bespoke wallpaper by Adéọlá

In the commissioned wallpaper design, Adéọlá invokes the spirit of the goddess Aje. Aje is goddess of abundance: a provider, symbolising shared prosperity and collective rather than individual gain. She represents an alternative to Western captialist ideas of wealth.

The wallpaper incorporates an imagined Vèvè (Vèvès are drawn representations of Yorùbá and Vodou spirits) as an offering to Aje, and bands of cowrie shells – often used in divinations as offerings to the goddess – form a striated pattern across the design. Cowrie shells were used as a currency of trade across Africa, and often have a spiritual or talismanic role. In the wallpaper, the cowries sit alongside bands of heavy chains, used by the Crawshays to demonstrate the quality of the metal produced at Cyfarthfa.

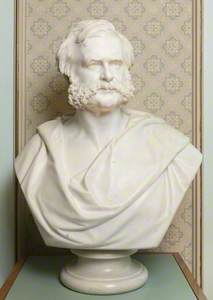

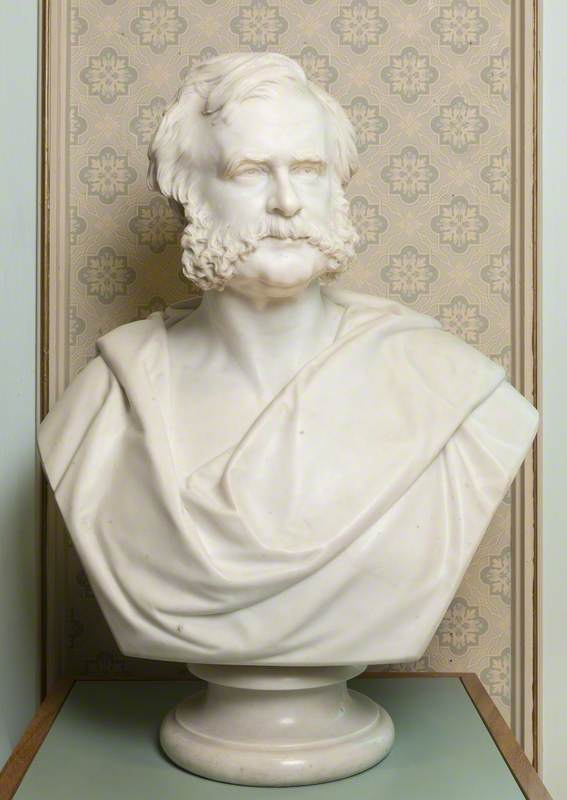

G. T. Clark (1809–1898), Esq., FSA

1872

Joseph Edwards (1814–1882)

Two powerful but contrasting symbols of wealth – cowrie and chains – run parallel in the wallpaper design, surrounded by images of items from Cyfarthfa's collection, such as the glowering face of G. T. Clark, manager of Dowlais Ironworks, in marble. A tiny pair of leather clogs – an 'untraced find' in the collection – acts as a reminder of the children impacted by industry, their stories and identities lost to us today. A Victorian grandfather clock speaks of workers and their labour – clocking in and clocking out – their time a commodity, owned and controlled by the Iron Masters. Adéọlá describes the items they encountered while exploring the collection as 'seemingly locked in time.'

Small leather child's booted clogs with wooden soles

perhaps 19th century, Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery

The room in which the commission is displayed was previously the children's playroom at Cyfarthfa, and there's a playfulness at work in the arrangement of objects and juxtaposition of images here: they echo and speak to each other, their interactions both deliberate and haphazard.

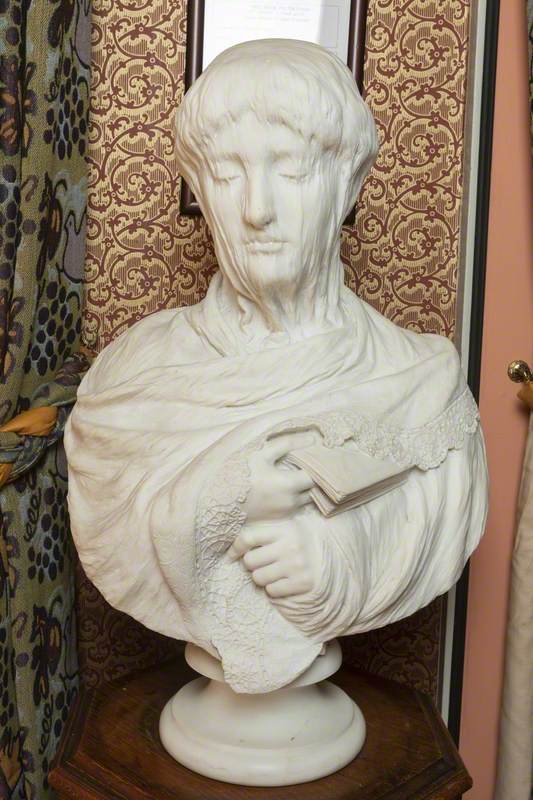

Veiled Woman is a marble sculpture by Orazio Andreoni, made in the nineteenth century. It shows the head and shoulders of a woman, her face half hidden under a veil. The veil creates ripples down her face, like rivulets of water, giving it a surreal, dream-like feel. Her eyes are closed, her hands emerging quietly from a shawl wrapped tightly around her shoulders. She holds a book in her right hand, her index finger sliding between the pages like a bookmark.

Sculptures of veiled women were popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. On the surface, they were a way of showing off the sculptor's technical skill – it's no mean feat to capture soft skin and veil in marble. But there is a gendered element at work, too. These veiled figures were usually girls or women, cast as 'types' – vestal virgins, brides, nymphs. As Adéọlá notes, 'a woman in a veil carries symbolism: being both seen and unseen.'

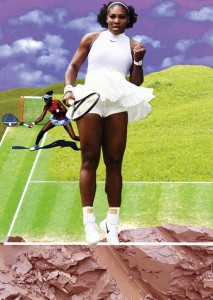

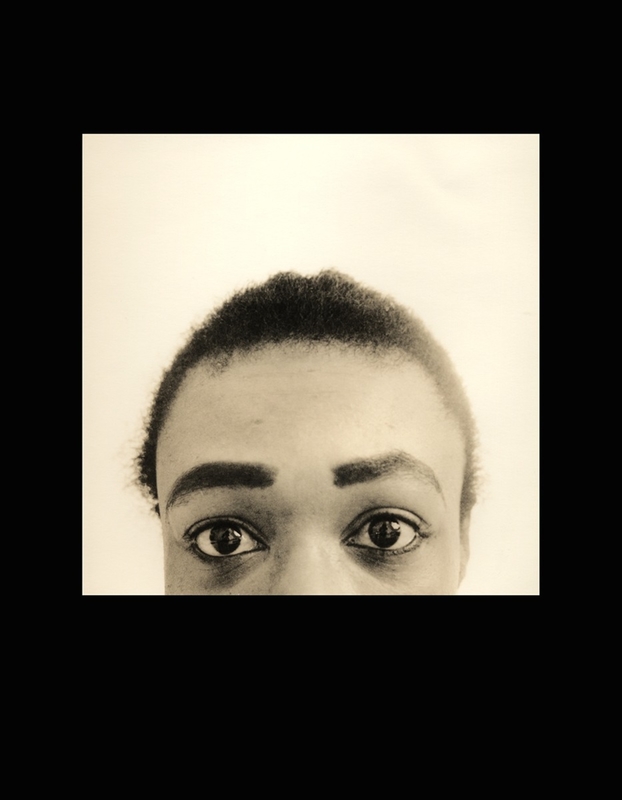

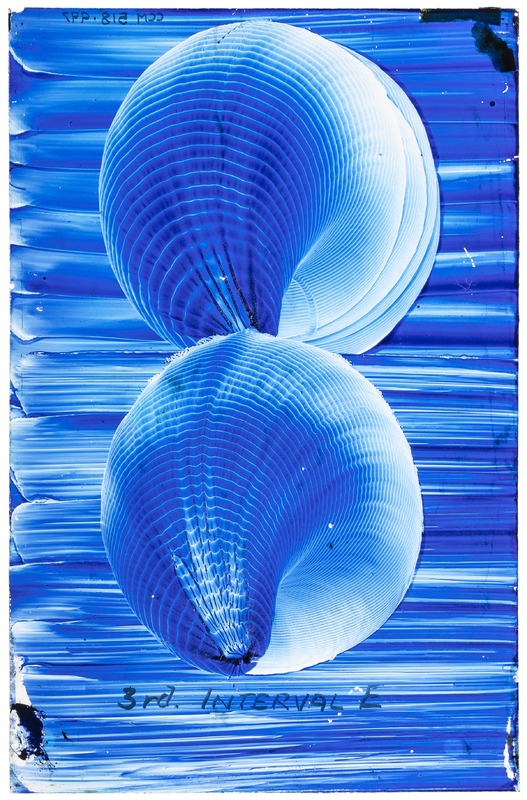

ain't I a woman?

2024, digitally manipulated photographic print by Catriona Abuneke

The tension between the seen and unseen carries through in Catriona Abuneke's photographic response, where the sculpture is partially obscured under layers, textures and patterns that call to mind chains, embroidered lace, ripples and refracted light: things that distort, conceal and reveal.

'ain’t I a woman?' installation view

Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery, 2024

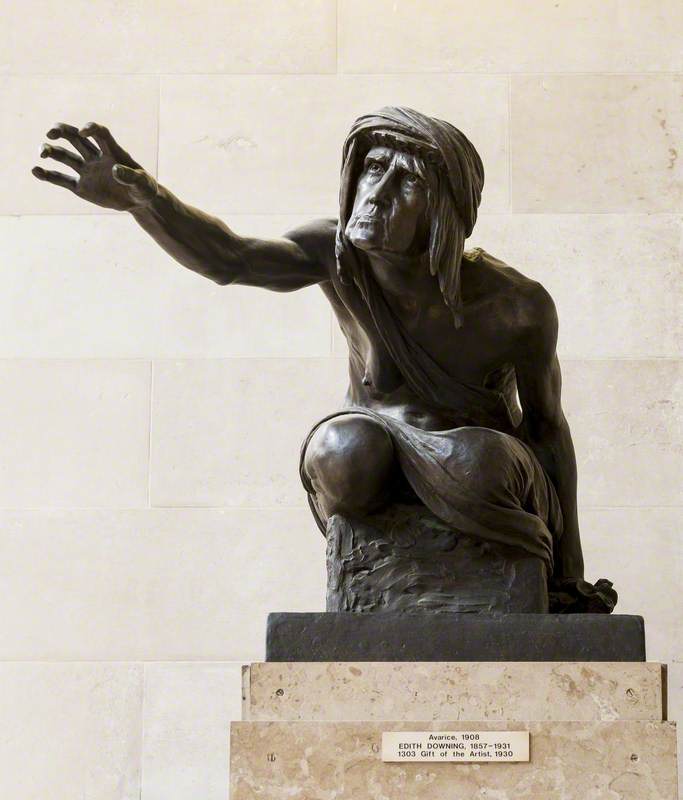

In another work, a photograph of The Elf by William Goscombe John is superimposed over a heavily textured, fiery orange-red background. The top half of the image is filled with textured layers: a grey herringbone pattern and sand-coloured stripes arranged horizontally, like a landscape receding in layers. The elf's skin echoes the patterns around her – like a chameleon. A reminder, perhaps, that our bodies are a complex play between the things we carry within us, and the things projected onto us.

The Elf was William Goscombe John's most successful design. He produced several versions. The Elf at Cyfarthfa is a smaller version of the life-sized marble made in 1899. Goscombe John's contemporaries praised it as a demonstration of his mastery over movement and form, but what they don't say is what we actually get: a young woman, elfin-faced, naked and crouching before us, the gentle twist of her body inviting us to circle around and consume her nudity from all angles. This returns us to the question 'What You See is What You Get?', and the realisation that sometimes the biggest truths are hidden in the things that remain unsaid.

View this post on Instagram

Steph Roberts, Commissioning Editor Wales at Art UK

'ain't I a woman?' is at Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery until 22nd December 2024, part of Ffoto Cymru: Wales' International Festival of Photography

With thanks to Adéọlá and Catriona Abuneke for providing valuable insights into their work at a 'Meet the Artists' event at Cyfarthfa Castle on 20th October 2024

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Further reading

Eric Williams, Capitalism & Slavery, University North Carolina, 1994

Chris Evans, Slave Wales: the Welsh and Atlantic Slavery 1660–1850, University of Wales Press, 2010

Diana Bestwish Tetteh, 'Photo Cymru: 5 to See', Aesthetic Magazine, October 2024

'Were there Black Suffragettes in Britain?', Find my Past, 2020

.jpg)