To mark this year’s Refugee Week we are focusing on four artists in The Higgins Bedford’s current exhibition ‘We Are Ten’ who sought safety in this country.

You can see all these works in the exhibition ‘We Are Ten’ until 28th January 2024. The exhibition celebrates ten years since The Higgins Bedford opened its doors following a major redevelopment.

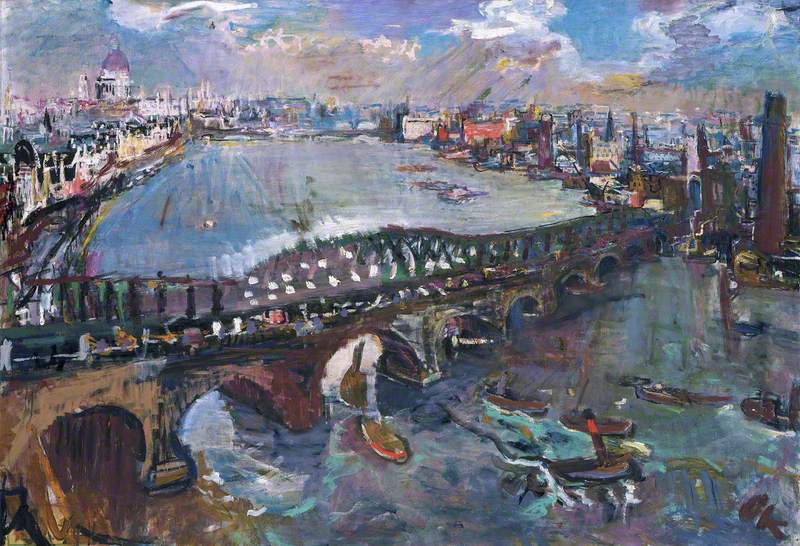

Oskar Kokoschka

The Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka was forced to flee his home to escape the rise of Nazism. He settled in Prague in 1934, but during this time the German government labelled him a 'degenerate artist'. He became one of many modernist artists that the Nazis saw as a threat to their ideals, they removed them from teaching positions and in some cases stopped them making art. 20,000 ‘degenerate’ artworks were removed from German museums and public collections, including hundreds of works by Kokoschka.

When Prague came under the threat of Nazi invasion in 1938 Kokoschka and his wife escaped to Britain. He became a British citizen in 1947.

Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980)

Watercolour on paper

H 40.5 x W 59.6 cm

The Higgins Bedford

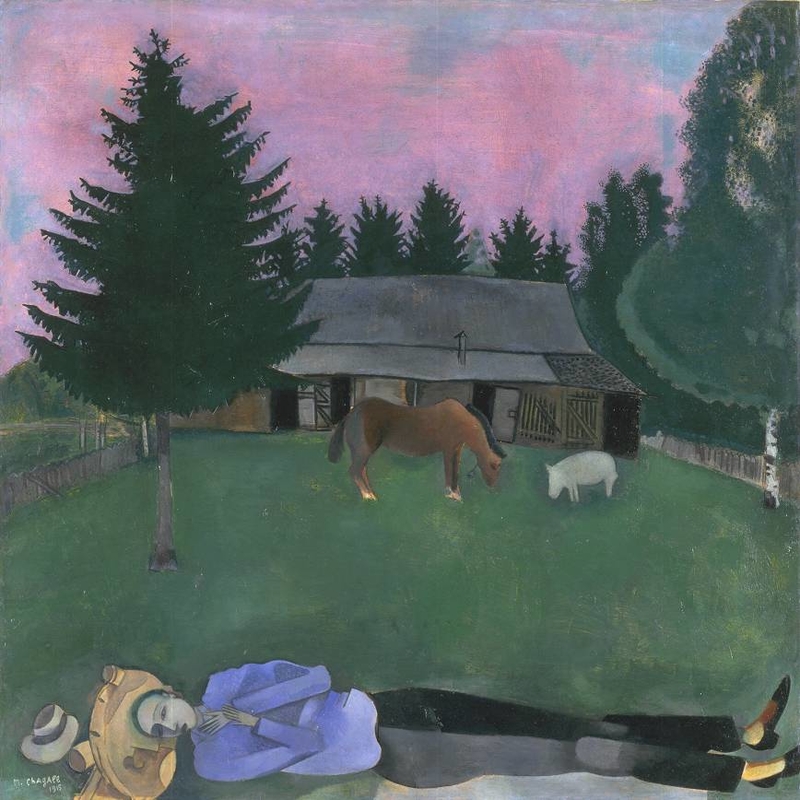

Marc Chagall was another ‘degenerate artist’ who was forced to escape his home.

In 1940 he was living safely with his family in Paris, but in June the city fell to Nazi Germany. Initially they thought they would be safe to stay, but when the French signed an armistice it quickly became clear that Jews living in occupied France weren’t safe.

A rescue effort was started by an American journalist called Varian Fry to help Chagall and others escape. The family travelled through Spain and Portugal before crossing the dangerous waters of the Atlantic to the safety of New York.

It was in New York that Chagall took up lithography, with his first major lithography series ‘Tales from The Arabian Nights’, of which this print is one of thirteen in the series.

Marc Chagall (1887–1985)

Lithograph on paper

H 31.7 x W 27.7 cm

The Higgins Bedford

Refugees have found a home in Britain for hundreds of years. Our next two artists are the sons of refugees, their fathers both fled their homes in Europe and went on to contribute hugely in their chosen fields here in the UK.

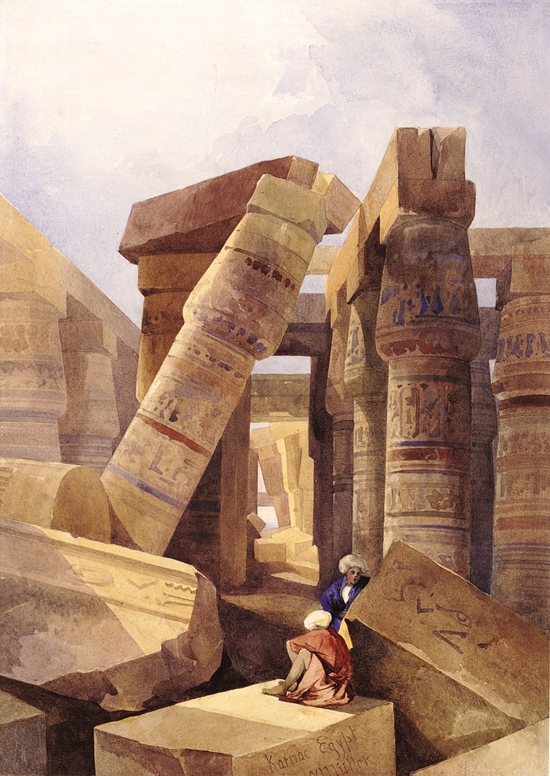

William James Müller

William’s father was the naturalist Johann Müller (1799–1830)¬ known in Bristol, where he settled, as John Samuel Miller. Miller was born in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), but was forced to escape the city in the middle of the night when it became part of Prussia.

He arrived in Bristol penniless, but soon settled. He became close with members of the cities Philosophical and Literary society due to his knowledge of Natural History and Geology. He was appointed as the first Curator of the Bristol Institution, which later became the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. He wrote a history of the Crinoidea which is still used by scientists today. As a child William would draw shells and models in the museum’s collection.

William James Müller (1812–1845)

Watercolour & bodycolour on paper

H 44.4 x W 31.5 cm

The Higgins Bedford

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Rossetti’s father, Gabriele Rossetti (1783–1854), was also a curator. Gabriele was forced to leave Naples in 1821 as a political refugee after a poem he had written criticising the King caused him to be branded as a traitor and sentenced to death. He fled to Malta before settling in England in 1824.

He married the daughter of another Italian exile and became Professor of Italian at King’s College, London. His four children all became celebrated artists or writers.

It was from his father that Dante Gabriel Rossetti got his love of the Italian poet Dante, whose story of Paolo and Francesca he depicts here.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

Watercolour on paper

H 31.7 x W 60.3 cm

The Higgins Bedford

Refugees

This year’s Refugee Week theme is Compassion which is exactly what Dorothy Hawksley shows in her painting of refugees from 1945. Nothing is known of the subjects in the painting, but it is likely that she is depicting some of the 65 million people who were displaced by the Second World War.

During workshops with Ukrainian refugees we asked what title they would give this work now. Many saw parallels with their own situation and titled it ‘Saving our Lives’ and ‘The Hope to Still be Alive’. One lady called it ‘Losses and Hope’, and the group agreed that although the people in the picture had lost a great deal there was always still hope for them.

Dorothy Webster Hawksley (1884–1970)

Watercolour & bodycolour on paper

H 42.4 x W 60.8 cm

The Higgins Bedford