(b ?Colle di Vespignano, nr. Florence, c.1270; d Florence, 8 Jan. 1337). Florentine painter and architect. Giotto is regarded as the founder of the central tradition of Western painting because his work broke away decisively from the stylizations of Byzantine art, introducing new ideals of naturalism and creating a convincing sense of pictorial space. His momentous achievement was recognized by his contemporaries (Dante praised him in a famous passage of The Divine Comedy, saying he had surpassed his master Cimabue), and to succeeding generations it was clear that a new artistic era began with him: in about 1400 Cennino Cennini wrote that ‘Giotto translated the art of painting from Greek into Latin and made it modern.’ He was the first artist since antiquity to achieve widespread fame, the demand for his services coming from all over Italy: early sources suggest that he worked in Assisi, Bologna, Ferrara, Lucca, Milan, Naples, Padua, Ravenna, Rimini, Rome, Urbino, and Verona, as well as Florence, and according to Vasari he also visited Avignon in France, where he is said to have carried out commissions for Pope Clement V (reigned 1305–14).

Read more

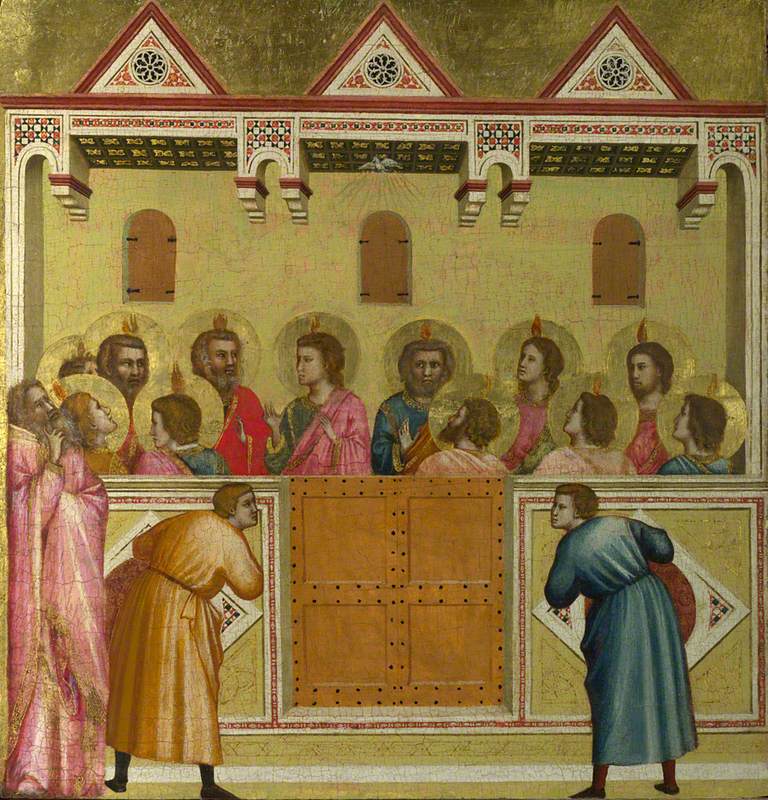

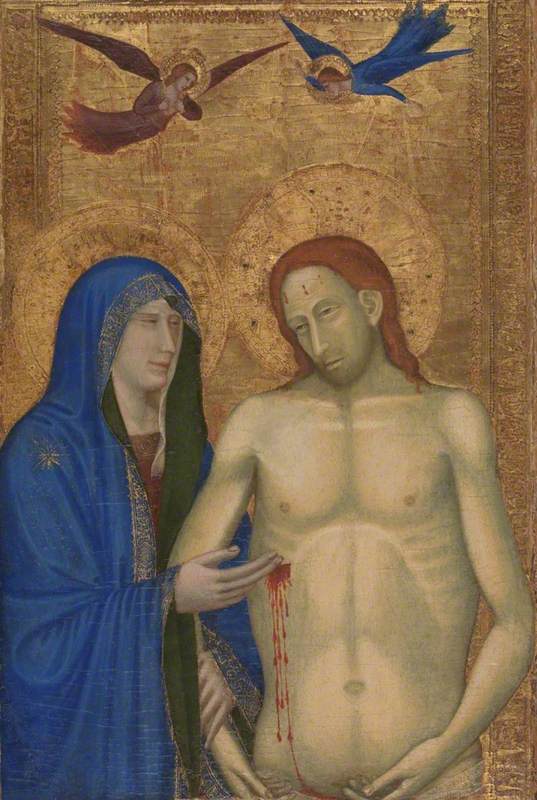

However, these early references tend to be frustratingly vague, many of the works they refer to are unidentifiable or have been destroyed, and no surviving painting can be given to Giotto on the basis of unimpeachable contemporary documentation. His work, indeed, poses some formidable problems of attribution, but it is universally agreed that the fresco cycle in the Arena Chapel at Padua is by him (he is credited with it in two separate literary references dating from c.1313), and it forms the starting point for any consideration of his work. The Arena Chapel (so-called because it occupies the site of a Roman arena) was built by Enrico Scrovegni (see donor), one of Padua's leading citizens, in expiation for the sins of his father, a notorious usurer mentioned by Dante. It was begun in 1303 and Giotto's frescos are usually dated c.1303–6. They run right round the interior of the chapel, which is virtually devoid of architectural ornament and clearly was conceived with painted decoration in mind (Giotto himself may well have been involved in the design of the building): the west wall is covered with a Last Judgement, there is an Annunciation over the chancel arch, and the main wall areas have three tiers of paintings representing scenes from the life of the Virgin and her parents, St Anne and St Joachim, and events from the ministry and Passion of Christ. Below these scenes are figures personifying Virtues and Vices, painted to simulate stone reliefs—the first grisailles. The figures in the main narrative scenes are about half life-size, but from reproductions it is easy to imagine they are much bigger, because Giotto's conception is so grand and powerful. His figures have a totally new sense of three-dimensionality and physical presence, and in portraying the sacred events he creates a feeling of moral weight rather than divine splendour. He seems to base the scenes on personal experience, and no artist has surpassed his ability to go straight to the heart of a story and express its essence with gestures and expressions of unerring conviction.The other major fresco cycle associated with Giotto's name is that on the life of St Francis in the Upper Church of S. Francesco at Assisi. This was first specifically given to him by Vasari and the attribution was not doubted until the 19th century; subsequently the question of its authorship has become one of the most controversial issues in the history of art. The St Francis frescos are clearly the work of an artist of great stature (their intimate and humane portrayals have done much to determine posterity's mental image of the saint), but they are more anecdotal and less powerful than the Arena Chapel frescos—stylistic differences that to many critics seem so pronounced that they cannot accept a common authorship. Other authorities, however, argue that the differences can be explained by Giotto maturing as his career progressed (the Assisi frescos are probably earlier than the Arena Chapel frescos, but their dating too is contentious). Attempts to attribute other frescos at Assisi to Giotto have met with similar controversy (see also Master of the Legend of St Francis; Master of St Cecilia). There is a fair measure of agreement, however, about the frescos associated with Giotto in S. Croce in Florence. He probably painted in four chapels there, and work survives in the Bardi and Peruzzi chapels, generally dated to the 1320s. The frescos are in very uneven condition (they were whitewashed in the 18th century), but some of those in the Bardi Chapel on the life of St Francis remain deeply impressive. Among Giotto's other major works was an external mosaic for Old St Peter's, Rome, showing Christ walking on the waters and popularly known as the Navicella (‘little boat’—a reference to the vessel carrying the Apostles, which symbolizes the Church, in which the faithful find refuge). The mosaic was saved when Old St Peter's was demolished and part of it is displayed in the portico of the present church, but it has been so heavily restored that it can no longer be regarded as Giotto's work. It is not known when he visited Rome, but during his stay he would have seen the work of Pietro Cavallini, which was as important an influence on him as that of Cimabue, who is traditionally (and highly plausibly) said to have been his teacher. The best documented period of Giotto's career is the time (1328–33) he spent at the court of Robert of Anjou, King of Naples. He had an honoured place in the royal household, but only small fragments survive of the paintings he carried out for Robert (Vasari says they included ‘portraits of many famous men’, including a self-portrait—among his rare secular works). In 1334, following his return from Naples, he was appointed city architect in Florence and in this role began the celebrated campanile (bell tower) of the cathedral (the design was altered after his death, but his essential concept was followed and the building is sometimes called ‘Giotto's Tower’). The panel paintings associated with Giotto are not as controversial as the frescos, but they nevertheless present numerous problems. Several panels bear his signature, but it is generally agreed that the signature is a trademark showing that the works came from his shop rather than an indication of his personal workmanship. Similarly, the Stefaneschi Altarpiece (Vatican Mus.) is connected with Giotto in a credible early source, but it is now regarded as having only tenuous links with him. On the other hand, the Ognissanti Madonna (c.1305–10, Uffizi, Florence) is neither signed nor firmly documented (it is first recorded in 1418), but it is a work of such grandeur and humanity that Giotto's authorship has never been seriously questioned. Among the other panels attributed to him, the finest is the Crucifix in S. Maria Novella, Florence (returned to the church in 2001 after a lengthy process of restoration, which confirmed its outstanding quality). In the generation after his death Giotto had an overwhelming influence on Florentine painting; this declined with the growth of International Gothic, but his work was later an inspiration to Masaccio, and even to Michelangelo. These two giants were his true spiritual heirs.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)