'It is harder to imagine heaven than hell,' writes Darren Oldridge in his book on the Devil. Being irreparably flawed ourselves, it makes sense that it is easier to conjure ever more horrible images of suffering than to comprehend, let alone visually depict, perfection. It is no surprise then that the idea of hell has served as inspiration for so many artists.

Drawn together from ancient myth, Biblical scripture, and literature, the concept of hell has evolved in the Western collective cultural imagination, enduring as a powerful metaphor even though belief in hell as a physical reality might have declined.

Miniature from 'Hours of Catherine of Cleves'

c.1440, illustrated manuscript by Master of Catherine of Cleves (active c.1435–1460)

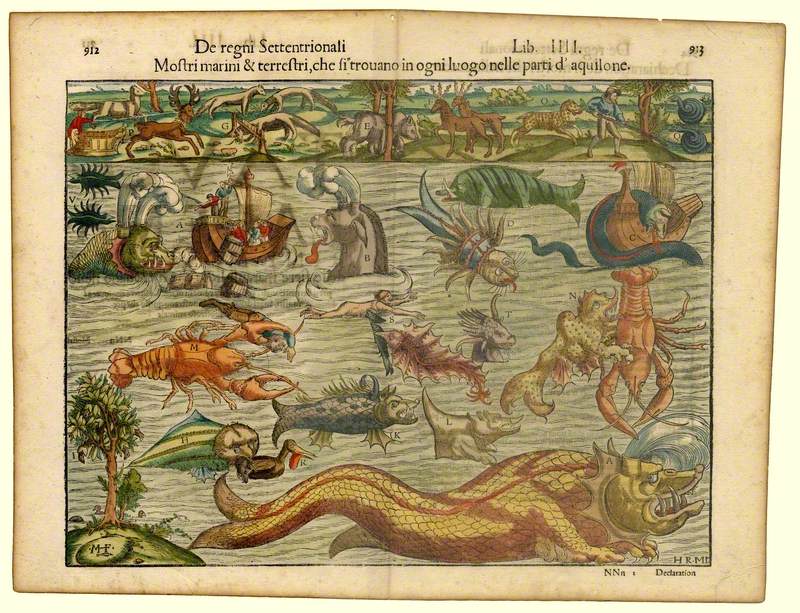

Early artistic depictions of hell allude to the syncretism of pagan and Christian ideas during the latter's early years. The hellmouth – the entrance to hell portrayed as the gaping mouth of a monstrous animal – is such an example. It first appeared in Anglo-Saxon art, and is thought to have been drawn from illustrations of the Norse myth of the battle between Fenrir, a wolf-creature, and Odin's son, Víðarr.

There is such an illustration on the mid-tenth century Gosforth Cross in Cumbria, which features Víðarr holding back a monstrous jaw, an image also thought possibly to represent Christ defeating Satan. A hellmouth also appears in the mid-twelfth century Winchester Psalter. The damned are locked up in an open animal mouth by an angel. Here, the hellmouth is simultaneously the entrance to hell and part of hell itself. The crush of bodies, which would become a motif in later depictions of hell, also alludes to the idea that the damned will be many while the righteous will be few.

‘Winchester Psalter’ or ‘Psalter of Henry of Blois’

mid-12th C, vellum illuminated manuscript by unknown artist

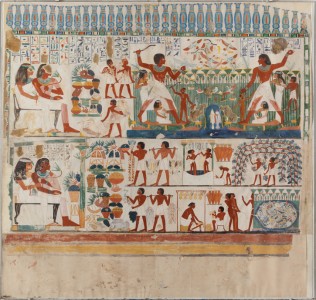

Images of damned souls became popular in the Middle Ages as Doom paintings and Last Judgement images proliferated. These were works that illustrated the apocalyptic last days and were often strategically positioned so congregations could meditate on the fate that potentially awaited them. The Last Judgement in the Florence Baptistery adorns its ceiling. Part of a series of mosaics begun in 1225 by the Franciscan friar Jacobus, the hell section (formerly attributed to Florentine painter Coppo di Marcovaldo) shows Satan as an anthropomorphised beast, resting each foot on a sinner's back while devouring another. Around him, toads swallow damned souls and lizards chomp at their limbs. Explicit images of torture would feature heavily in paintings of hell for hundreds of years.

Last Judgement

1306, fresco by Giotto di Bondone (1266/1267–1337)

In Giotto di Bondoneo's Last Judgement in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, a flow of lava cascades downwards towards a blue-black cave, bringing with it the bodies of the condemned who are to be put through a variety of inventive torments. Giotto's friend, the poet Dante Alighieri, is said to have visited the painter while he was working on the fresco. Giotto's hell, which exudes coldness as opposed to intense heat, may have inspired Dante's pit of ice in Inferno, which in turn would have a profound effect on artistic imaginations for centuries. Inferno depicts Dante's descent into the now infamous nine concentric circles of hell. In each ring Dante and his poet guide Virgil witness contrapasso, where the punishment ironically befits the sin.

Last Judgement and Hell

c.1335–1340, fresco by Buonamico Buffalmacco (c.1315–1336)

The idea of a hell with defined sections would appear in paintings like the Camposanto Monumentale di Pisa frescoes, attributed to Buonomico Buffalmacco. Here hell is cave-like and segmented into tiers. Inspired by both Giotto and Dante, a three-faced devil sits in the middle with bloodied limbs hanging from each mouth. The grotesqueness of these images also betrays a sardonicism which is appropriate as they could also offer social satire.

The Map of Hell

c.1480–1490, silverpoint & ink, coloured with tempera on manuscript, by Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510)

Over a century later, Sandro Botticelli would spend 20 years illustrating Dante's work. Unlike many of the other images also inspired by poet, Botticelli's Map of Hell (1485) presents the entire topography of hell with its concentric layers in one glance, conveying what Deborah Parker of The World of Dante online research tool calls hell's 'grand design'. From afar it appears like a chaotic torture factory heaving with bodies. Look closely and you can appreciate the painstaking detail involved in illustrating Dante and Virgil's journey. Botticelli's aim, it seems, is less to convey any cosmological hell than to pay tribute to Dante's particular vision.

The Garden of Earthly Delights

16th C/early 17th C

Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450–1516) (copy after)

Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights, one of the most enduring portrayals of hell, also attempts to convey a sprawling image of 'The Bad Place'. It is a city on fire, an anti-Eden with animals employed in tormenting, the landscape littered with instruments of torture, with every corner of the canvas offering a terrifying vignette. There is no obvious Satan figure, but a blue bird-headed creature simultaneously consumes and excretes humans, recalling the devils of Giotto and Giovanni da Modena. Bosch also conveys the mental anguish of his damned souls in their furrowed brows and open mouths. Particularly startling is a woman, whose appearance is uncannily like that of Eve, who closes her eyes to avoid seeing her reflection in the glass bottom of a grotesque creature.

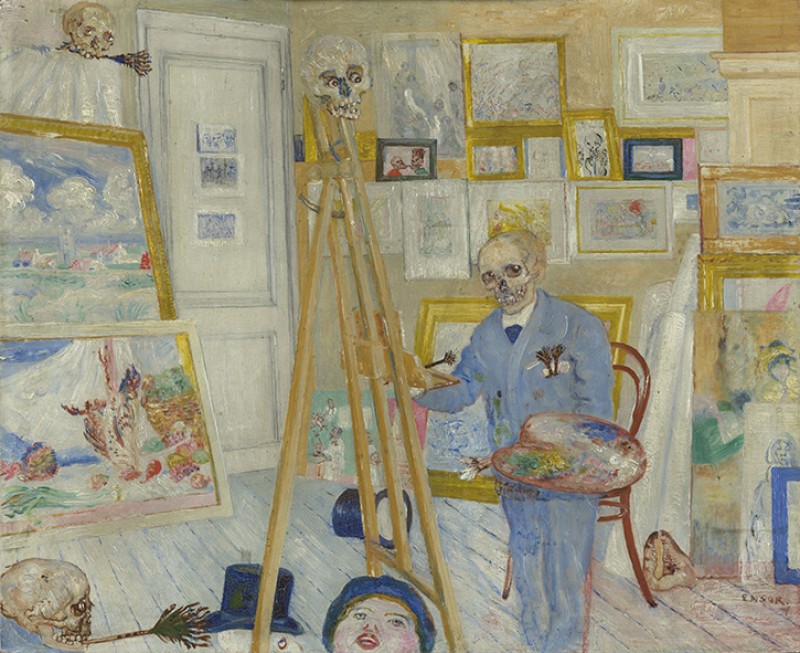

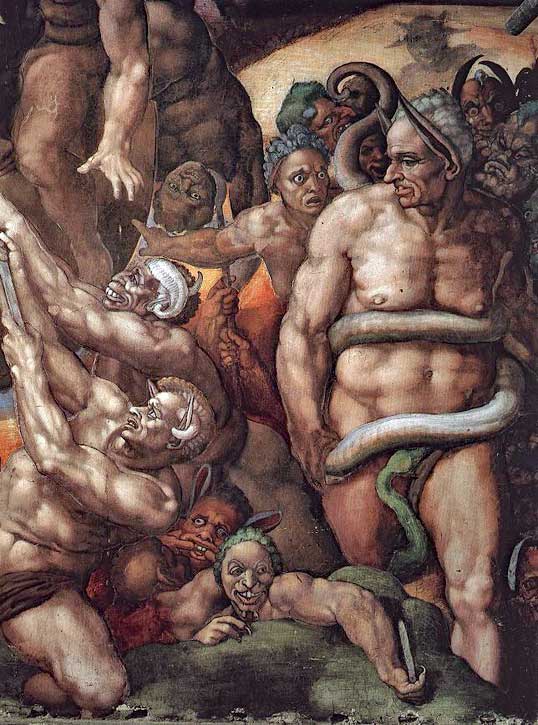

While Botticelli and Bosch aimed to depict pictures of hell in as much detail as possible, Michelangelo Buonarotti's The Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, which is probably the most well-known Doom painting, significantly only hints at hell. It is marginalised to the lower-right edge of the fresco, its presence an ominous threat with the horrors which were more explicitly illustrated in medieval works left to the imagination. Instead, Michelangelo's work emphasises the psychological terror of damnation, for example in the bulging eyes of a figure behind whom the flames of hell roar.

The Last Judgement

(detail), c.1537–1541, fresco by Michelangelo (1475–1564)

Artistic interpretations of hell would increasingly stress this psychological torment over medieval physical torture, picking up perhaps on Protestant ideas of hell as a state of permanent separation from God, and literature would continue to be a primary source of inspiration. In Paradise Lost (1667), John Milton states he wants his epic poem to 'justify the ways of God to man', but its most famous 'problem' is his compelling portrayal of Satan. Satan the antihero would especially inspire artists a century later who lived during, and in the wake of, the French Revolution.

The Fallen Angels Entering Pandemonium, from 'Paradise Lost', Book 1

?exhibited 1841

John Martin (1789–1854) (formerly attributed to)

In Thomas Lawrence's Satan Summoning His Legions, Satan takes centre stage in armour, looming over the viewer, a look of fury and vengeance on his classically beautiful and illuminated face. The smaller, more intimate framing minimises hell as a physical place and emphasises instead his fallen condition, recalling these lines from Paradise Lost: 'Which way I fly is hell; myself am hell.'

George Frederic Watts' Satan is an even more vivid example. Satan turns his face away, perhaps because of the intensity of the flames, perhaps because of shame. The shifting of hell from a physical place to a state of psychological suffering, in the end, does not lessen the effect of hell but puts its horrors into the realm of the unimaginable and the unportrayable. Satan is depicted as somebody who himself suffers in hell, rather than merely reigning over it as is implied in earlier images.

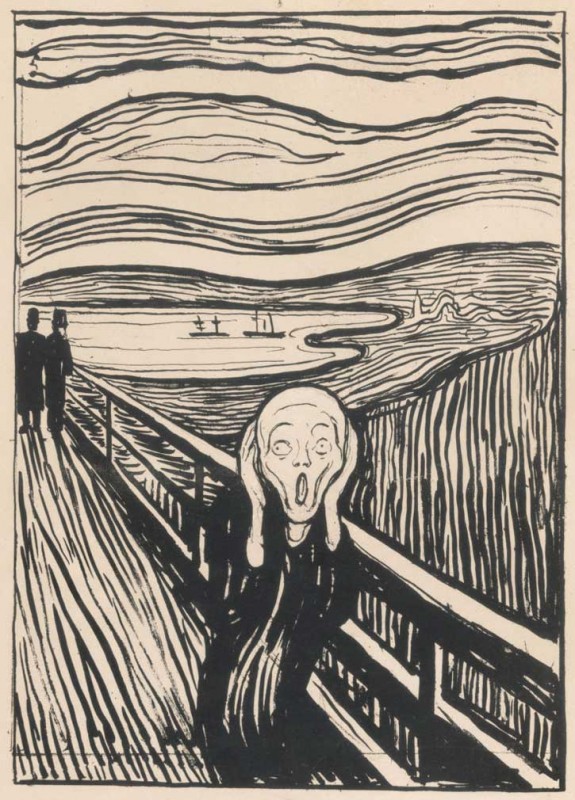

In Edvard Munch's Self Portrait in Hell of 1903, the painter stands naked and alone in his personal perdition. An ominous black shape looms behind him which could be a plume of smoke. His facial expression – particularly his eyes, which look directly at the viewer – does not portray the explicit anguish, but instead, the fiery yellow/orange/red surrounding him belies the torment his face does not express.

Self Portrait in Hell

1903, oil on canvas by Edvard Munch (1863–1944)

The abstraction of hell, in line with a decline in belief in it as a physical reality, has not prevented the concept from remaining a useful metaphor. Hell is used to describe not eschatological horror but horrors of our own making here, hell on earth, as Richard Phillips' Hell (2007) does by adapting Fra Angelico's Last Judgement, Hell.

View this post on Instagram

Phillips focuses on the image of the devil devouring human beings to comment on the war in Iraq and the indifference of political leaders to the destruction and loss of life.

Its use in our everyday speech as well ('that was hell', 'Twitter is a hellsite') might at first glance suggest the diminished power of the concept of hell to truly terrify, but one could also argue it signifies just how embedded the idea of hell as a place of suffering remains, a testament to its endurance over millennia, to which art has no doubt contributed.

Aida Amoako, freelance writer