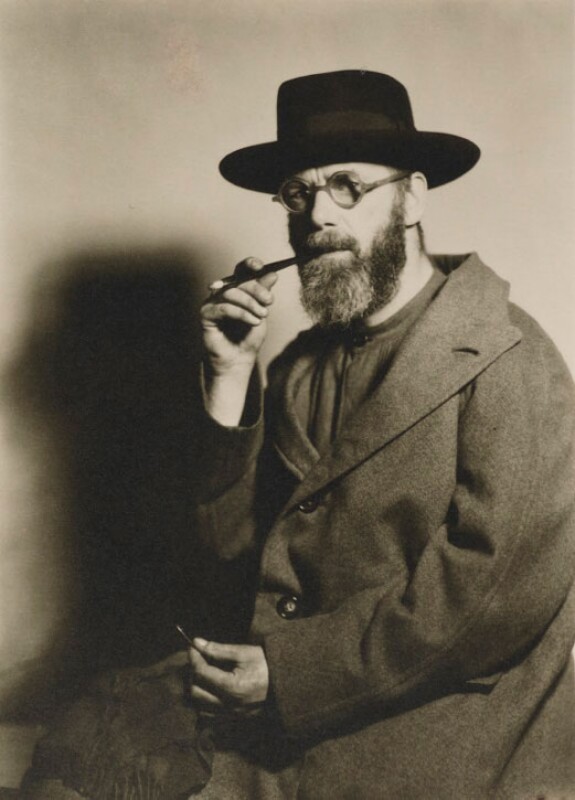

(Baptised Milan. 30 September 1571; died Port’ Ercole, 18 July 1610). The most powerful, original and influential Italian painter of the 17th century. Although his career was brief (he was only 38 when he died) and his output was fairly small (there are about 70 surviving pictures by him), he had an immense impact on his contemporaries, creating a bold and naturalistic style that broke decisively with the prevailing vapid Mannerism and inspired a host of imitators. His baptismal record, discovered in 2007, indicates that he was born in Milan, but he grew up in Caravaggio, near Bergamo, and takes his name from the town. From 1584 to about 1588 he served an apprenticeship in Milan under the undistinguished painter Simone Peterzano (c.1540–c.1596) and by about 1592 he had moved to Rome, which was to be the main centre of his activity. His career there is not firmly documented until 1599 and in his early years he is said to have endured hardship, taking on whatever hackwork he could to scrape a living. He progressed to assisting Giuseppe Cesari, then to independent work, and in the mid-1590s a dealer sold some of his pictures to Cardinal Francesco del Monte, who became his first important patron (Caravaggio was a paid retainer in his household for about three years, c.1597–1600).

It was probably through del Monte that Caravaggio gained his first public commission—two large canvases of the Calling of St Matthew and the Martyrdom of St Matthew for the side walls of the Contarelli Chapel in S. Luigi dei Francesi; they were painted in 1599–1600 and are his first documented works. An altarpiece of St Matthew and the Angel was added in 1602 and by this time Caravaggio had already completed a second major public commission—two paintings for the Cerasi Chapel in S. Maria del Popolo: the Crucifixion of St Peter and the Conversion of St Paul (1600–1). All these pictures, and particularly the last two, were immensely original in their dramatic use of light and shade, their economy and force of design, and their down-to-earth realism—the familiar stories being seen in a totally new way and played out by solid, substantial, flesh-and-blood people rather than the traditional idealized figures. They established Caravaggio as the most exciting painter in Rome and changed the direction of his career: from now on he devoted himself mainly to large, deeply serious religious pictures for public settings, rather than intimate works for the rarefied taste of connoisseurs.

From the beginning of his public career, his work was controversial, as many contemporaries found his realism inappropriate or abhorrent in a religious context. Several of his major works were refused on such grounds of decorum or theological incorrectness and were replaced with more conventional pictures by Caravaggio himself or other painters. Among the rejected paintings was the Death of the Virgin (1605–6, Louvre, Paris), which shows the Virgin as a thoroughly believable corpse rather than in the traditional way as a woman who appeared to be merely sleeping before being received into heaven. It was turned down by the church of S. Maria della Scala and replaced with a picture by Saraceni. Baglione writes that Caravaggio's picture was removed because he ‘so disrespectfully made the Madonna swollen up and with bare legs’, and another early account says that her figure was based on the body of a drowned prostitute fished out of the River Tiber. However, the controversial painting was soon bought by Vincenzo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua (on the recommendation of Rubens), and Caravaggio's other rejected pictures were likewise quickly acquired by discerning collectors, including Cardinal Scipione Borghese .

Whilst Caravaggio was becoming the most famous painter in Rome on account of such works, he was also achieving notoriety for his violent and loutish way of life. In the years 1600–5 he built up a lengthy criminal record for various cases of assault and insulting behaviour, then in 1606 he killed a man in a fight over a wager on a tennis match. He fled Rome, fearing he would be executed for murder, and spent the remaining four years of his life as a fugitive from justice, his travels taking him to Naples (1606–7), Malta (1607–8), Sicily (1608–9), and back to Naples again (1609–10). Wherever he went he gained important commissions and had a major influence on local artists. During these years his work became more austere and poignant, as in the Beheading of St John the Baptist (1608, Valletta Cathedral, Malta), his largest painting and a work of the utmost tragic power. His life continued to be fraught with danger: in 1608 he was imprisoned on Malta but escaped, and in 1609 he was badly wounded in the face in Naples. He died of fever on the way to Rome, where he thought a pardon was imminent. He had no pupils, but a legion of followers (the Caravaggisti), and his work, together with that of the Carracci, inaugurated a new era in Italian painting (see Baroque).

Caravaggio continued to be a famous name throughout the 17th century, but he was regarded by many as an ‘evil genius’ (in the words of Vicente Carducho, writing in 1633), whose influence on other artists was pernicious. In 1672 Bellori wrote ‘There is no doubt Caravaggio advanced the art of painting, because he came upon the scene when realism was not much in fashion and when figures were made according to convention and satisfied more the taste for gracefulness than for truth’; however, Bellori also thought he had ‘debased the majesty of art’, and that because of him ‘everyone did as he pleased, and soon the value of the beautiful was discounted’. Interest in Caravaggio declined in the 18th century (he is not mentioned in Reynolds's Discourses), but revived in the mid-19th century. By this time his rejection of ideal beauty could be seen to have the advantage of truth, although there were still those, like Ruskin, who saw in him ‘perpetual seeking for and feeding upon horror and ugliness, and filthiness of sin’. Serious historical research on him began in the early years of the 20th century, since when he has attracted an enormous amount of critical commentary and speculation, so much so that Ellis Waterhouse has written that ‘the innocent reader of art-historical literature could be forgiven for supposing that his place in the history of civilization lies somewhere in importance between Aristotle and Lenin’.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)