In celebration of St David's Day, here we share six works of art from Welsh collections that explore the beauty and resilience of yr iaith Gymraeg (the Welsh language).

Cymraeg is, for many of us, the language of hearth and home: the cornerstone of friendship, learning and community. It holds a treasured place in Welsh culture and identity. However, it has been forced to the edges of extinction many times in its long history, and campaigns to protect the language have been as fiercely fought as the many attempts to suppress, demean and erase it.

Despite the odds, Cymraeg has persisted, rich in its resilience. Today it is a vibrant, living language, and about 30% of the population of Wales can speak it. In the words of Dafydd Iwan's soul-stirring anthem, 'ry'n ni yma o hyd' (we're still here).

But there is no room for complacency. The language is still vulnerable, and many challenges are yet to be overcome. The following works stand testimony to the fire in the bellies of those who have – and those who still – fight for a more just, inclusive and expansive future for our language.

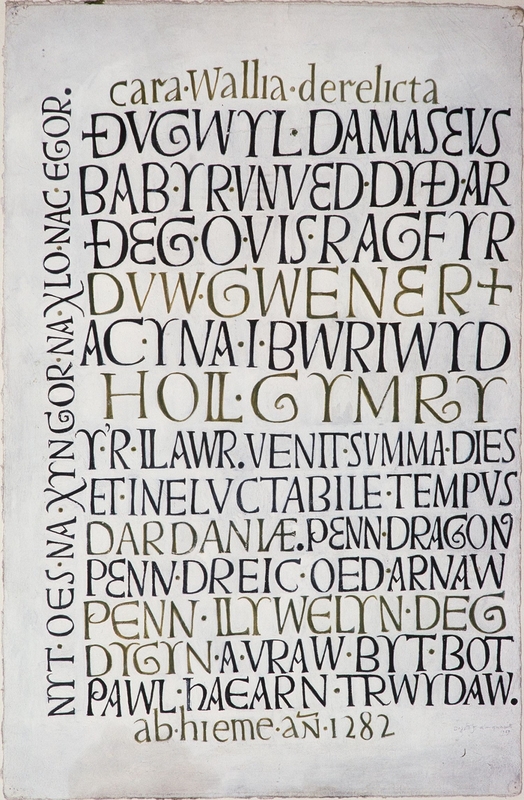

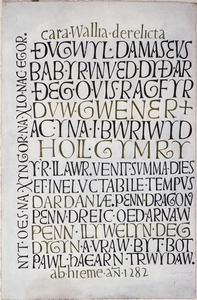

1. Cara Wallia Derelicta (1959) by David Jones

This mystical painted inscription by David Jones is a grief-stricken lament, held in the collection of the National Library of Wales. It combines medieval Welsh poetry with Latin taken from Virgil's Aeneid. Cara Wallia Derelicta translates to 'Dear, abandoned Wales', or in Jones' own words, 'poor buggered-up Wales'.

Jones is often called a painter-poet, and his work from the 1940s fuses word and image. He described medieval Welsh bards as 'carpenters of song', and this idea of crafting and shaping language into tangible form can be seen here: his calligraphic lettering forms abstract, rhythmic patterns on the page.

The work includes words taken from a marwnad (elegy or death song) by Welsh court poet Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Coch, mourning the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Llywelyn, the last native prince of an independent Wales, was murdered on 11th December 1282, decapitated, and his head taken to London as a trophy of English conquest. Soon after his death, Wales was subsumed under Edward I and the English crown.

This work draws parallels between the death of Llywelyn to the Fall of Troy – like many, Jones saw it as a catastrophic national loss from which he feared Wales might never fully recover.

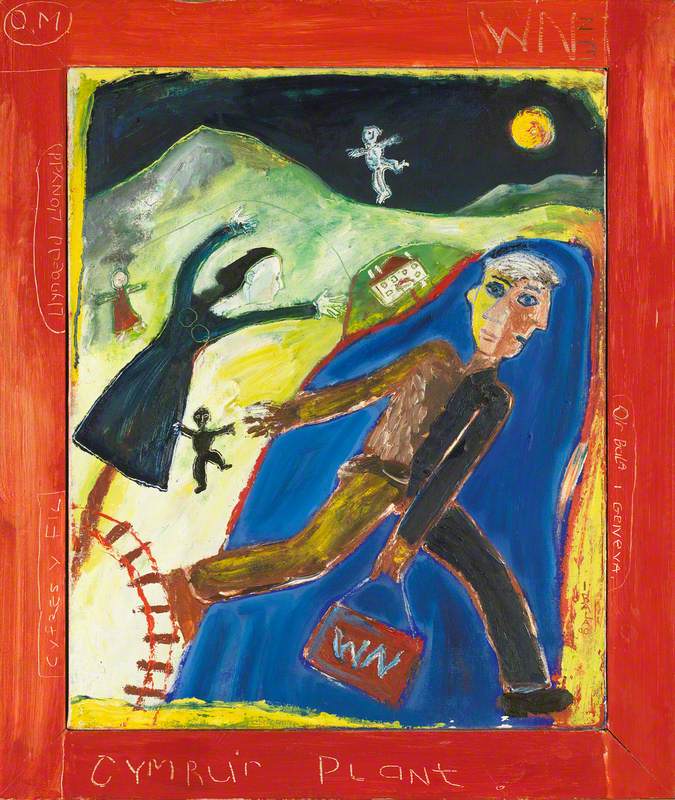

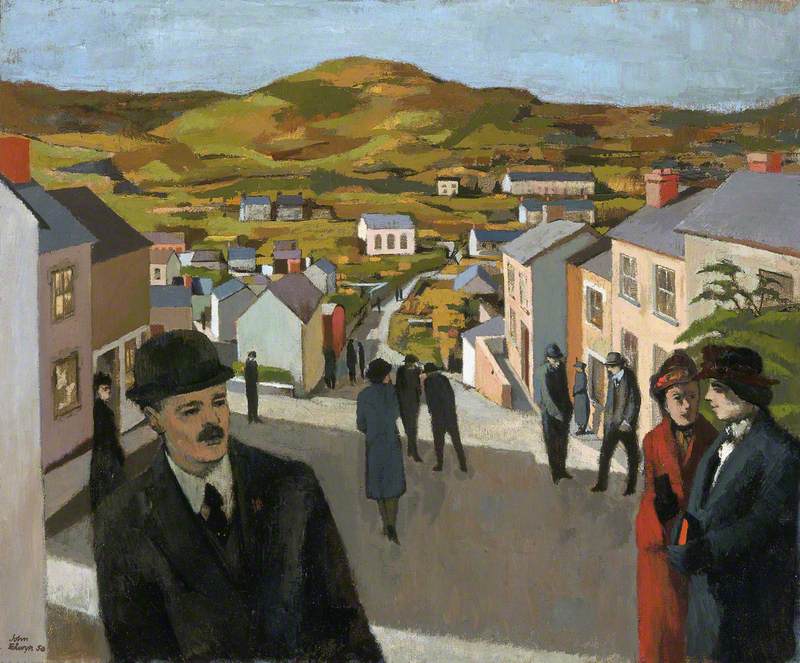

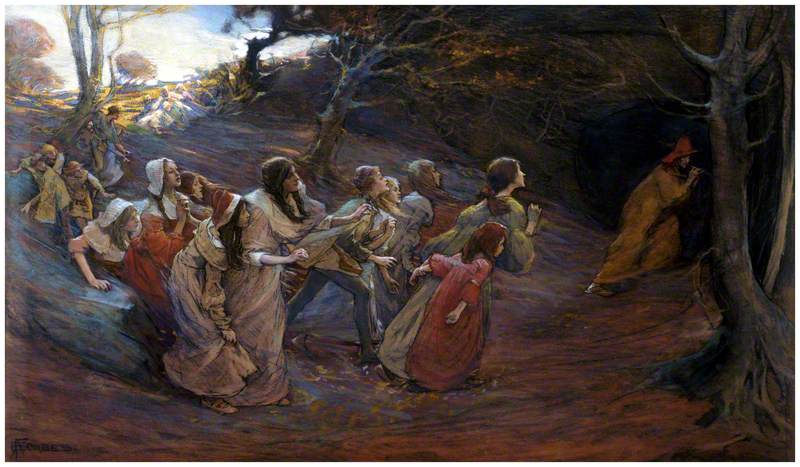

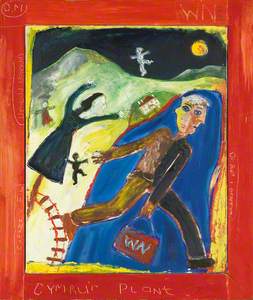

2. O. M. (c.1990) by Iwan Bala

A figure strides through the landscape, holding a Welsh Not. He appears almost embryonic, submerged in – or perhaps stepping out of – the waters of Llyn Tegid.

Owen Morgan Edwards (O. M.) was a prominent figure in Wales' national awakening in the late nineteenth century. He campaigned tirelessly for the Welsh language to be taught in schools, and was a pioneer in Welsh language publishing at a time when the language was in decline.

His autobiography, Clych Adgof (1906) describes being regularly punished at school for speaking in his native tongue. The Welsh Not was used across Wales as a punitive and cruel attempt at suppressing the language, by those who thought English was the only path to progression.

O. M.'s son, Ifan ab Owen Edwards, founded Urdd Gobaith Cymru, today the biggest Welsh-medium youth movement in Wales. The Urdd's residential activity centre, Gwersyll Glan-llyn, is shown here on the lake shore.

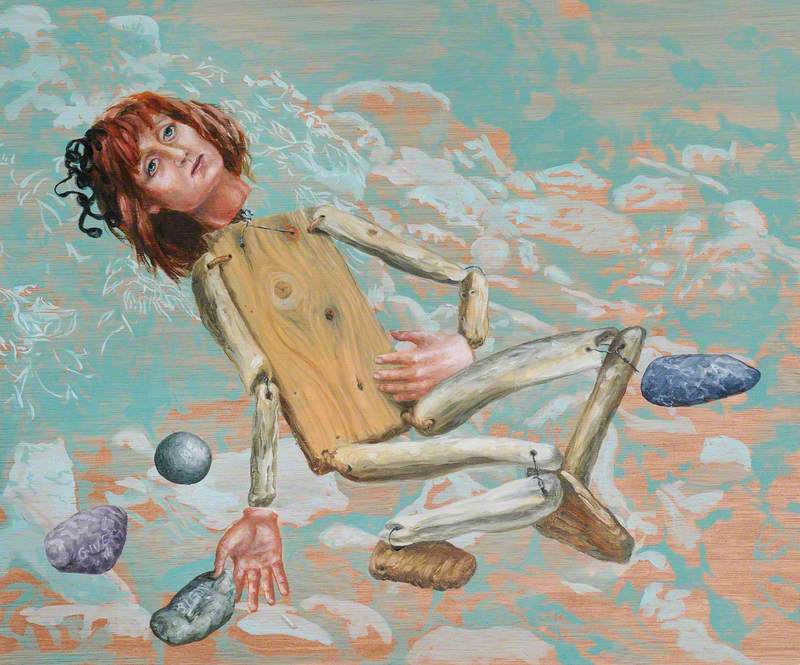

3. Mair at Cylch Meithrin (2020) by Anya Paintsil

Mair at Cylch Meithrin shows the artist's sister crying with her toy duck, Floppy. It's based on a memory from Anya's time at Cylch Meithrin, a Welsh-medium playgroup. Cylchoedd Meithrin play an important role in nurturing future generations of Welsh speakers and is a popular nursery choice across Wales.

In an interview with Lydia Figes, Anya described her experience as being one of the few mixed-race students in a Welsh language primary school. 'We always felt different and out of place,' she said. 'Reclaiming the Welsh language in my work is a way to protect my Welsh identity because so many people throughout my life have questioned it.'

For Anya, being a Welsh speaker is an important part of her identity as a Welsh and Ghanaian artist. But despite Wales having one of the oldest ethnically diverse communities in Europe, some people see Welshness – and the Welsh language – as exclusively white, a grave misconception which still causes rifts within the Welsh-speaking community.

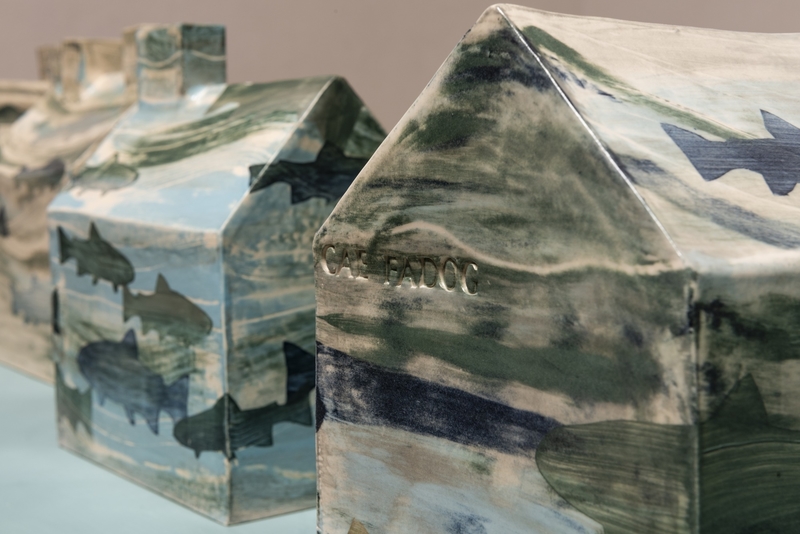

4. Cofiwch Dryweryn / Remember Tryweryn by Emily Jenkins

Eleven ceramic cottages are arranged according to the layout of Capel Celyn, a small village in the Tryweryn Valley. Capel Celyn was a close-knit Welsh-speaking community. Residents were forced out of their houses as their entire valley was drowned in 1965, to supply Liverpool with water.

The drowning of Tryweryn was experienced as a direct attack on Welsh language and rural life, and an indication of the political apathy towards Wales of the Westminster MPs who passed the bill.

It led to decades of protest, and was one of the main events that fuelled Saunders Lewis' rousing lecture Tynged yr Iaith (The Fate of the Language), in which he argued that immediate revolutionary action was the only thing that could save the language from extinction.

Feelings of anger and betrayal still run deep, and the slogan 'Cofiwch Dryweryn' remains a clarion call for those who refuse to forget. The sculptor John Meirion Morris created a maquette for a public memorial on the shores of Llyn Celyn, but it has never been erected.

Here the cottages are decorated with swirling waves and fish silhouettes. Each cottage has its original Welsh name stamped into the clay: an act of honouring and remembrance. The work was purchased by CASW and is now at MOMA Machynlleth.

5. O Bydded i'r Hen iaith Barhau (c.1960–1980) by Lauretta Williams

Following Saunders Lewis' Tynged yr Iaith lecture, thousands of people across Wales, mostly students, were stirred to action. In 1962, Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (Welsh Language Society) was formed, to advocate and campaign for language equality.

O Bydded I'r Hen iaith Barhau

c.1960–1980

Lauretta Williams (1910–1993)

Bilingual road signs were a major part of these campaigns. In the 1960s and 1970s, protesters plastered English-only signs with green paint, and later smashed and destroyed them as the protests escalated in intensity.

This painting shows an imagined demonstration. Campaigners are holding Welsh-language road signs, and placards with slogans like Cyfiawnder (Justice). Some protestors are being dragged away by police. Over 180 members of Cymdeithas yr Iaith were taken to court during these protests, and some were imprisoned, including Dafydd Iwan. Bilingual road signs became a legal requirement in Wales in 1993, with the arrival of the Welsh Language Act.

The title of this painting is taken from the chorus of Wales' national anthem, and translates as 'may the old language endure'.

The painting is in the collection of Parc Howard Museum (Carmarthenshire Museums Service), which owns over 40 works by the artist Lauretta Williams.

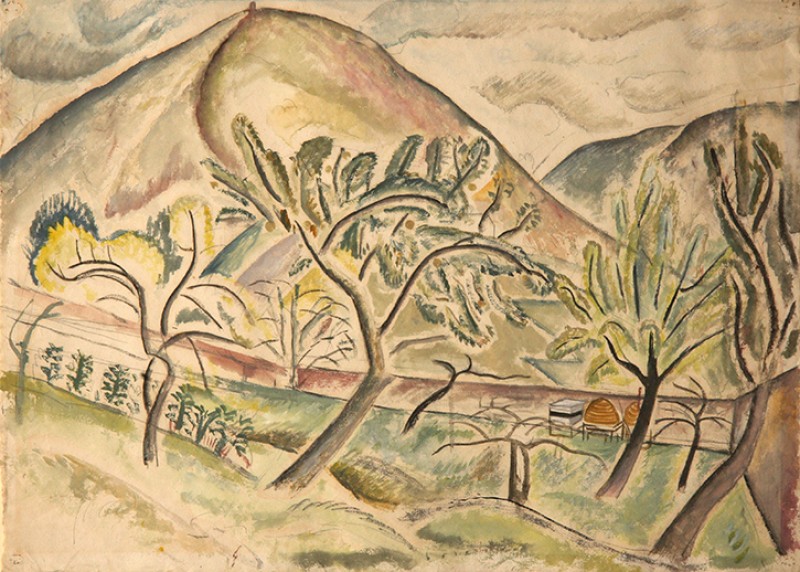

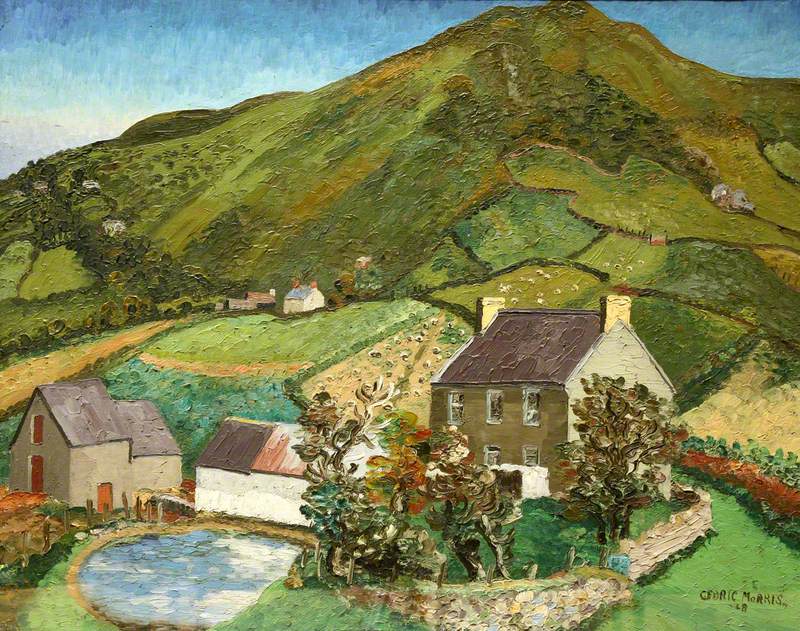

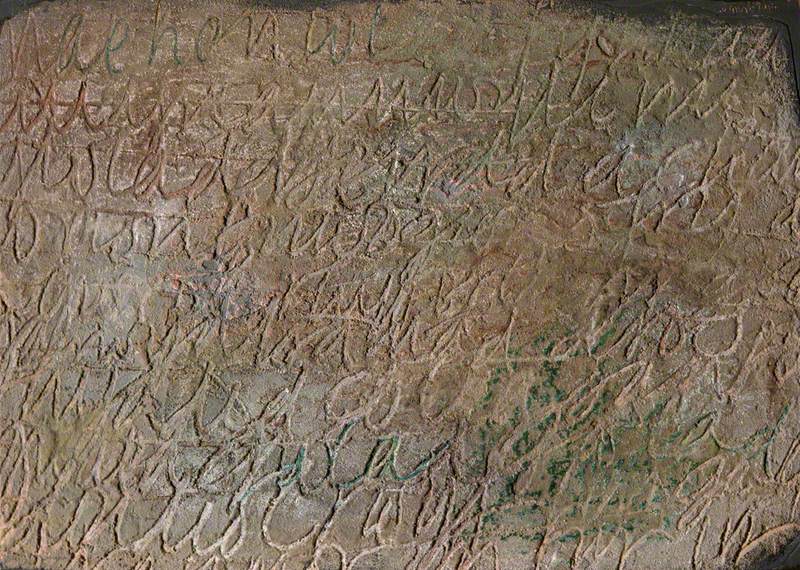

6. 'Mae Hen Wlad fy Nhadau…'/'Land of my fathers' (1975) by Ogwyn Davies

'Mae Hen Wlad fy Nhadau…'/'Land of my fathers'

1975

Ogwyn Davies (1925–2015)

Lyrics from Wales' national anthem are scrawled onto a textured plaster surface. They loop and overlap in a rhythmical dance, and are crossed out in places, making it difficult to read. The work, which is on long-term loan to National Museum Wales from the Derek Williams Trust, is reminiscent of graffiti scratched into an old weathered wall or a page in a school book. The artist, Ogwyn Davies, was at the time a teacher in Tregaron, a strong Welsh-speaking community in west Wales.

The plaster has been mixed with local sand and stone, and ceramic dust from his studio. His approach was inspired in part by an exhibition of Catalan artist Antoni Tàpies at the Glynn Vivian in 1974.

The national anthem was written by father and son Evan and James James in Pontypridd in 1856. This was the first time Ogwyn used the anthem in his work. The lyrics became an ongoing motif that he returned to time and again. He described being in 'regular attendance at international rugby matches, where to hear thousands sing the National Anthem is a very moving experience.'

Steph Roberts, Art UK Commissioning Editor – Wales

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Further reading

Betsan Powys, 'Tryweryn: The stories behind drowned village Capel Celyn', BBC News, 2023

E. Wyn James, 'Painting the word green: Dafydd Iwan and the Welsh protest ballad', Cardiff University, 2005

Ceri Thomas, Ogwyn Davies: Bywyd a Gwaith / A Life in Art, Y Lolfa, 2022

Shakira Morka, 'Unseen: Young, Black and Welsh', Nation Cymru, 2022

Wales.com, 'Land of my fathers: Wales' national anthem'