This essay was written for the 2024 Write on Art prize, winning first place in the Year 12 & 13 category.

I think that Manet would have liked Pauline Bunny. As for Hugh Hefner, I'm not so sure. There is something of Manet's Olympia in Pauline Bunny's unidealized form; the two works are united in their stark confrontation of Laura Mulvey's 'male gaze,' as they pose a quietly incendiary challenge to the voyeurism typically imposed upon works of the female body.

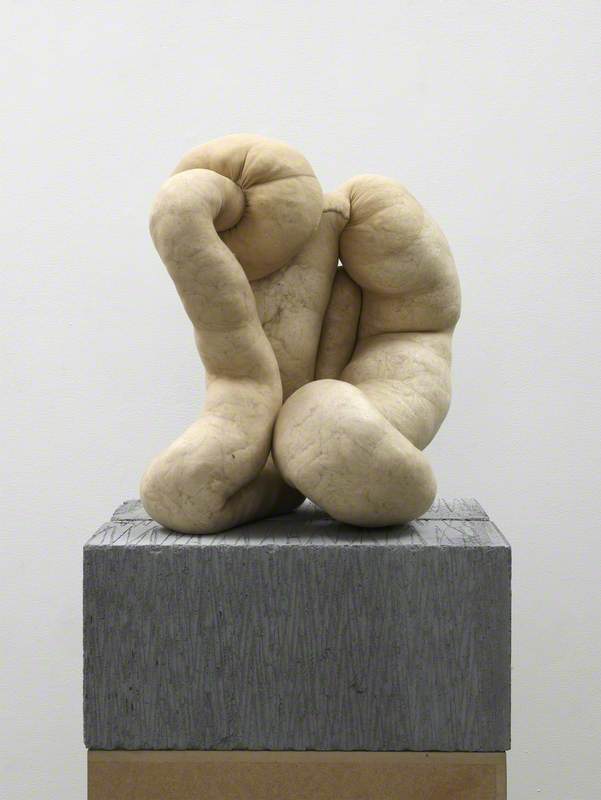

Sarah Lucas's sculpture, constructed from a pair of stuffed pantyhose, puns on the infamous Playboy bunny, an iconic symbol of female sexual availability in the late twentieth century. However, the inherent erotica of the sculpture's title is sharply undercut by the sagging form of the abstracted figure and the emptiness of its lolling head. Chair-bound, Pauline Bunny provides a perfect symbol of the female passivity espoused by Hefner and his contemporaries, yet in appropriating the pornographic imagination of her peers, Lucas effectively satirises the fetishisation of the female body. As Elizabeth Manchester suggests, 'the process of objectification itself… is revealed to be both comic and ridiculous, a self-defeating reduction which turns its object into something laughably undesirable.'

I find that there is something incredibly daring in Lucas's decision to not only expose the voyeuristic male gaze, as avant-garde nineteenth-century artists such as Manet did, but to actively mock it instead. Rather than simply holding misogyny up to the light, Lucas laughs in its face. The flaccid drooping of the bunny's phallic ear-appendages evokes a sense of almost ridiculous fantasy as Lucas derides the notion that this acquiescent figure is an object of desire. The sculpture is the ultimate gesture of distaste for the sexual appetites of the Playboy generation, a comedic two-finger salute to the idea that women should just 'take it' and be subordinate, open, available.

Nonetheless, Lucas's sardonic exploitation of the macho language of her society – the bunny, in her nylons and office chair, is redolent of a kind of 'secretarial submissiveness' – belies a more sinister truth about the disempowerment of women during the postmodern period. The sculpture was originally part of an installation titled 'Bunny Gets Snookered', which reinforces its themes about the abuse of the female body; in the language of the game, being 'snookered' means being prevented from scoring, reflecting the impotence of women at the time. According to Sterling Ruby, Lucas's work is often concerned with the use of sculpture as a 'stand-in for the physically collapsing body.' Consequently, the distorted appearance of the bunny, which treads the line between 'sexualised formalisation and figurative abstraction' reflects women's chaotic attempts to reconcile themselves to their society's crass hyper-sexualisation of their bodies.

Lucas's artistic generation, the Young British Artists, is known for being confrontational. Messy, punkish, urban, raucous – sharks in formaldehyde, unmade beds littered with condoms – their artwork speaks to a London so vibrant and virile that anything seems possible. Lucas, too, taps into the raw energy of the new millennium, yet in Pauline Bunny, a rougher, seedier edge of the cultural revolution is exposed. The sexual fervour sours. I was thirteen years old when I saw Pauline Bunny exhibited at the Tate Modern, standing on the cusp of girlhood and womanhood. Even then, Lucas's wry commentary on the nature of female objectification seemed to strike a chord in me, a chord which only intensified as I began to navigate a world in which female sexuality is couched in the dictatorial terms of the patriarchy. Today, it is easy to discount Pauline Bunny as increasingly irrelevant, a relic of a bygone 'Playboy era'. Nonetheless, recent onslaughts on female reproductive rights ensure that Pauline Bunny is still resonant – and that makes me afraid.

Amelie Roscoe

Further reading

Laura Mulvey, 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,' Screen, volume 16, 1975, pp.6–18

Ruby Sterling, 'Sarah Lucas's Pauline Bunny,' Tate Etc., 29, 2013, pp.1–3