This essay was written for the 2024 Write on Art prize, winning third place in the Year 12 & 13 category.

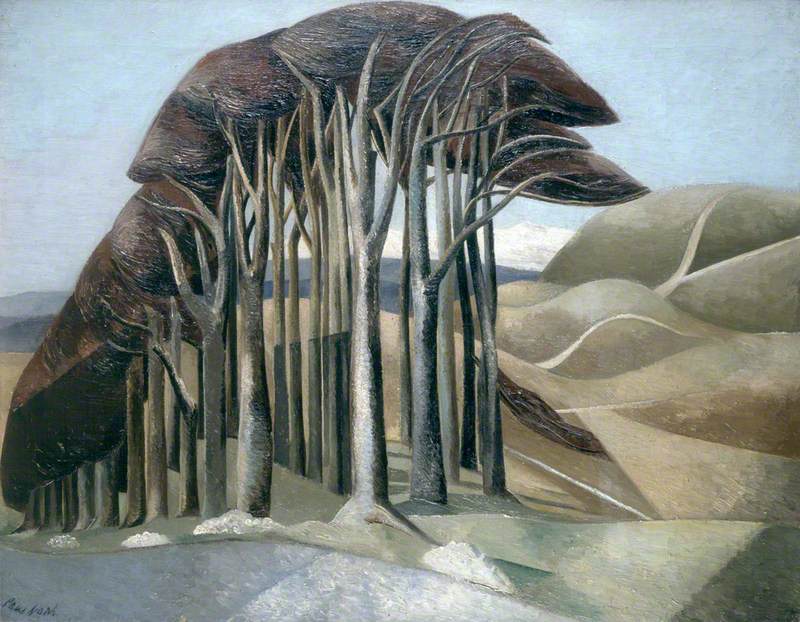

Dawn rises upon a shattered landscape, illuminated by blinding crepuscular rays that only serve to bring light to mankind's destruction of nature, reflecting the deep irony in Paul Nash's title We Are Making a New World.

Olive greens and umbers in the foreground, that have been rendered almost like flesh, entrap the viewer into the shattered horror of no man's land. In his diary, Nash wrote 'I have tried to paint trees as tho' they were human beings' and upon closer inspection we can see the individualisation of the trees, allowing the viewer an insight into what Nash himself would have witnessed: a landscape fraught with the dead bodies of his comrades. It is a piece that reflects Nash's sombre state of mind, absorbed in his disgust for war, and the complex emotions of a man recovering from a broken rib after falling into a trench in Ypres in 1917, which has been described by Andrew Graham Dixon as a 'comical mishap.' But it was one that ultimately saved his life, as shortly after his incident, when he was brought back to England, his entire regiment was wiped out in the Battle of Passchendaele. Subsequently he returned as an official war artist on a personal mission to expose the futility of war.

The roughly worked mounds of earth, formed by dynamic brushstrokes of layered oil paint, appear to mimic gravestones amid the desecrated landscape: a landscape that, from the destruction of man, has become unrecognisable, desolate and forsaken. To heighten the almost tangible irony of this piece, Nash has depicted ebony trees emerging from the veridian green of the background – a representation of false hope that the war is over but we must still burden the weight of its catastrophic consequences. I certainly agree with Andrew Graham Dixon when he said 'the churned earth is like burned flesh, the tree stumps like mutilated limbs and the red clouds in the sky are like scarred and angry flesh.' However, I believe the trees represent entire bodies rising out of the mud, destroyed and shattered but still oozing with the blood of fury and accusation.

Growing up, I spent three years living in the UN Buffer Zone in Nicosia that was established after the Cyprus civil war. This area appears to be trapped in time, untouched since the fighting. Nash's piece therefore resonates with me, as I grew up surrounded by the consequences of war. As a child I was blissfully unaware of the events that transpired to result in the destroyed landscape I called my home. Now older, and looking at my childhood in hindsight, I feel I can empathise with Nash's anger at the destructive consequences of war.

A striking yet vulnerable sun illuminates the eldritch trees and appears to be in danger of being engulfed by the red mountains, that are like blood staining the landscape. I agree with former curator at the Imperial War Museum Roger Tolson, who claimed that 'in Nash's bitter vision the sun will continue to rise each day to expose the desecration... This new world is unwanted, unlovable but inescapable.' Nash has brought light to the cataclysmic consequences of the First World War that we feel the effects of still today, like the sun that relentlessly rises upon us, every day, mocking man's pitiful ambitions of war and echoing the deep irony of We Are Making a New World.

Evie Wildish