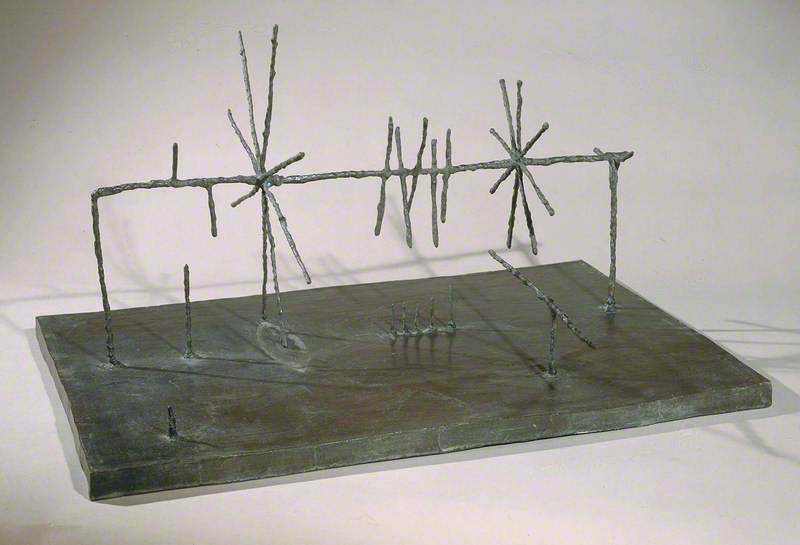

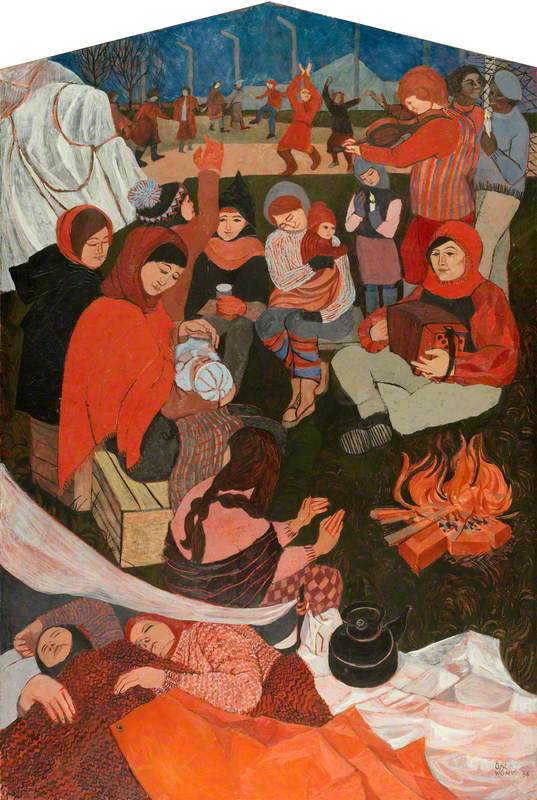

When I was little, the sculpture towered over me. It looked like a brown butter knife, sticking up straight in a pat of cold, hard butter.

I thought it was advertising The Fitzwilliam Museum café. It reminded me to ask mummy for a Smarties cookie. It also made me think of the big girls at ballet, balanced on one foot, en pointe. Could I ever be so still, so graceful? Depending on whether I got my cookie, it might also appear like half a broken scissor like the ones at school, incomplete.

As I grew older, I learnt my planets. The crusty patina looked like fiery moles on the planet's surface. I would not be able to breathe there, in that dense, toxic atmosphere. Nor could I stand against its weight – I too would be squashed thin like a knife.

As I grew, it loomed a little less. But then I saw the woman in it. Diving into a dappled pool, toes lines at the peak, an upside-down Botticelli. She is not climbing out of a scallop shell but she is nude, nonetheless. Pared to the bone.

Venus is the love of Mars, but she is hotter. Sometimes she is the protector of chastity in young girls, sometimes the patroness of prostitutes. Why think of such things?

In my early teens, I realised that Venus was a razor for smooth legs. Perhaps the sculpture is a plastic surgeon's knife for cutting women into shape?

This piece is 'Number 3' of five. It is like the phallic middle finger boys hold up in corridors.

Venus is the only female planet amongst all those men. She spins 'retrograde,' as they say. But what if, like a woman, she is the only one who is doing it right? She does not tilt as she spins, she has no change of seasons, she is as vertical as a plumb line.

Perhaps this blade is the one that castrated her father, Uranus, whose organs, thrown upon the sea, birthed her?

She is made of blades. A Boudica – a Joan of Arc – throwing herself into life headfirst. This is not a sword in the stone for men but a blade in the bronze for women.

Miranda Black, first-place winner of Write on Art 2022, Years 10/11