In the 2021 England and Wales Census 1.5 million people identified as having a sexual orientation other than heterosexual and 262,000 people did not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth. Named as the 'Queer Generation', the visibility of queer people is only rising but their existence is by no means a twenty-first-century phenomenon.

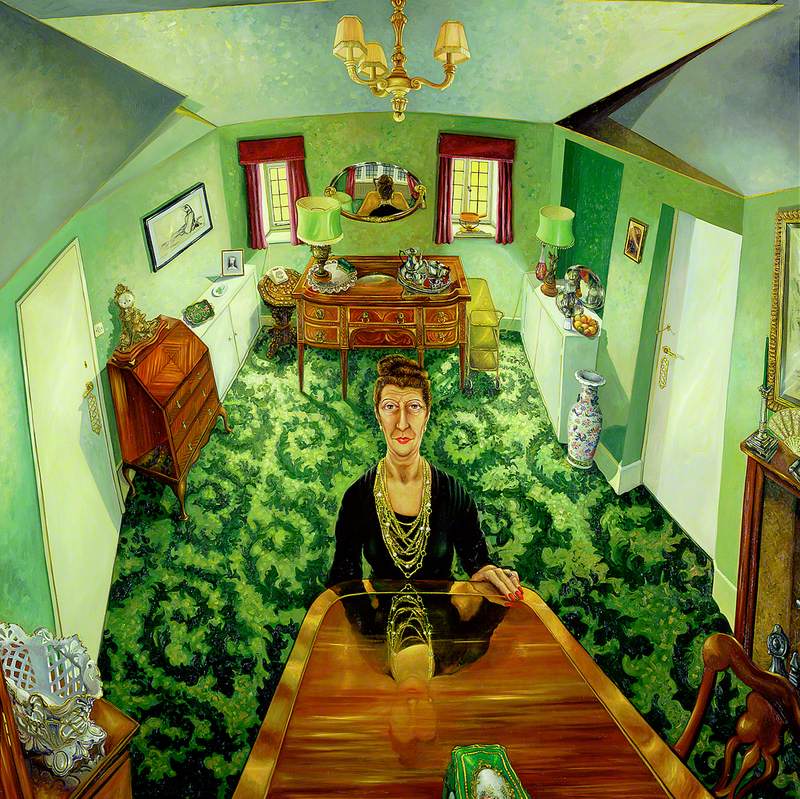

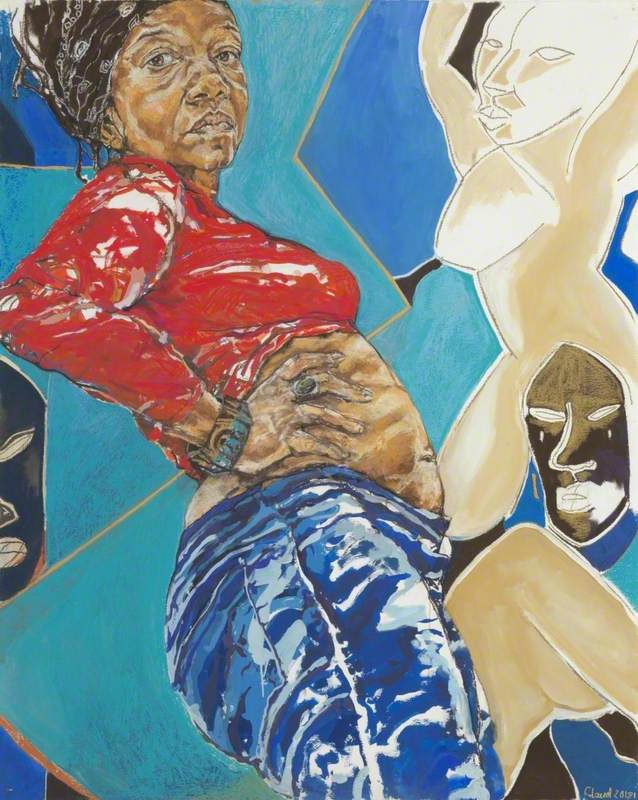

A defiant downwards gaze, the confident and commanding figure stares straight at you as if questioning your opinion of them. But this strong gaze is tainted by a sense of sadness and weariness, lines of tension marking out the bold features of their face, with the glint in their eyes drawing the viewer into the face of Gluck's self portrait of 1942. Warm visible brushstrokes allow the face to become human and emotive – there is a connection between you and this stranger.

Gluck presents an image of themself that dominates the space, the cool white background complementing the range of pink flesh tones in their face, of which the crowning features are the dark brown eyes that lay central in the picture plane, gleaming in the light. The only source of true colour is a kerchief around their neck which drapes around an upturned collar, an inch of their clothing revealing a subversive masculine identity. The cropped brown hair swept back with confidence presents a defiant image of queer expression at a time of suppression, discrimination and disdain.

The distress visible in their eyes reflects a person who has been subjected to a consistent rejection from British society – unable to be free from either gender or sexual expectations. It is also a human image of grief and anger – Gluck's 1936 painting Medallion (YouWe) marked the 'marriage' of wealthy Nesta Obermer and Gluck and became an iconic image of lesbian love after being published as the cover of the Virago 1982 edition of Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness, a book which presents a butch lesbian identity which was heavily censored until 1949. When Nesta Obermer ended the relationship after refusing to leave her husband, the 1942 self-portrait was created as a lament of this lost love. I believe this grief transforms the painting into a personal symbol of the years of visibility and love lost to an oppressive society.

Gluck's defiant persona is visible through the canvas – their androgynous clothing and strong masculine features asserting to the viewer a knowledge of self-identity present in the artist, with no attempt to hide their age or experience. Desiring to be named as 'Gluck no prefix, suffix, or quotes' asserts their identity beyond traditional gender roles. At the time neither lesbian nor transgender identities were recognised by the government, as when a Conservative MP stated that all 'acts of gross indecency by females' should be made illegal it was dismissed; it was thought that the mere mention of lesbianism would lead women astray. The gaze of Gluck appears to push through this barrier asserting their strongminded, determined nature as the viewer locks eyes with them, exploring their face from their chin along the bridge of their nose and outwards a wholly human experience of examining one another.

This piece is unlike any traditional self-portrait I have come across – a simple assertion of identity, a universal image of defiance and anguish at lost love and an oppressive government. These ideas are vitally emotive at a time in 2023 when the existence, rights and acceptance of these identities are continually questioned. Gluck's self-portrait serves as an image of hope for the future by looking back to the queer defiance of the past.

Ophelia Lanfranchi, third-place winner of Write on Art 2023, Years 12/13

Further reading

Amy de la Haye and Martin Pel, 'Gluck: Art and Identity', Yale University Press London Blog, 2018

'The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1885', The British Library