This essay was written for the 2018 Write on Art prize, winning first place in the Year 10 & 11

Picture the scene. It’s a typical, wet February day in south Wales. You slip off the M4, and five miles down the road into Swansea. Out of the damp misery, you step into the

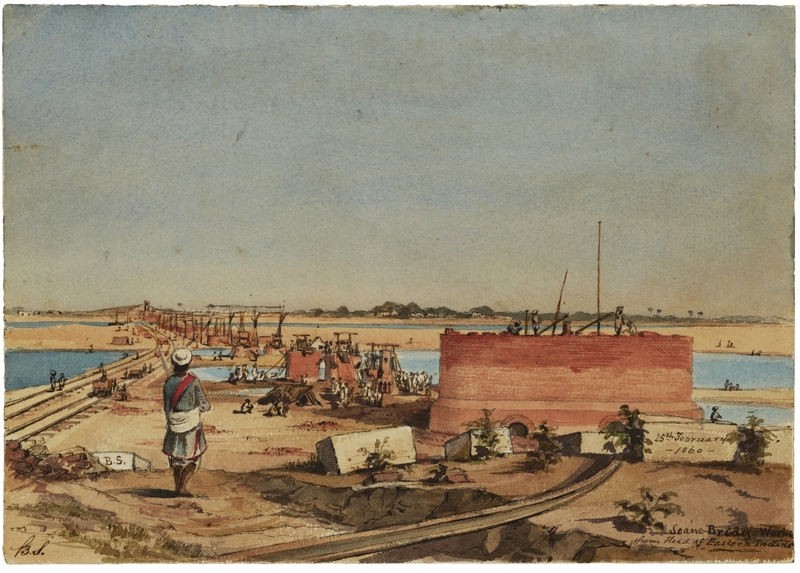

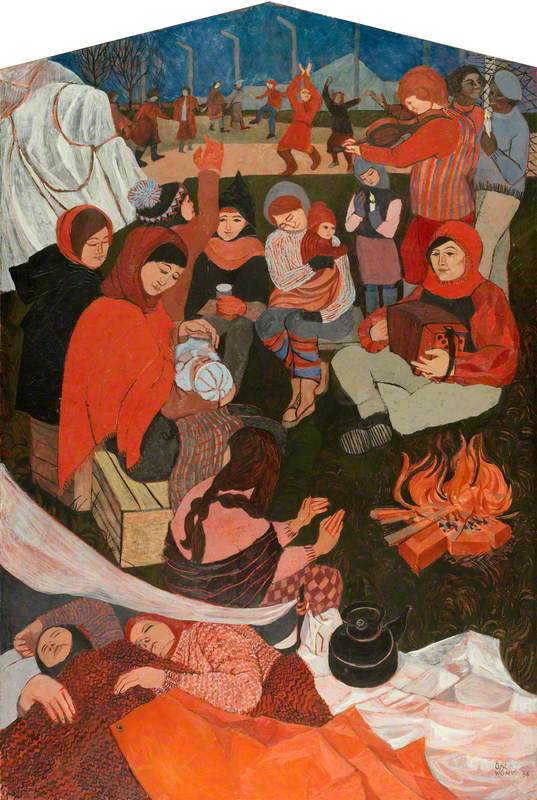

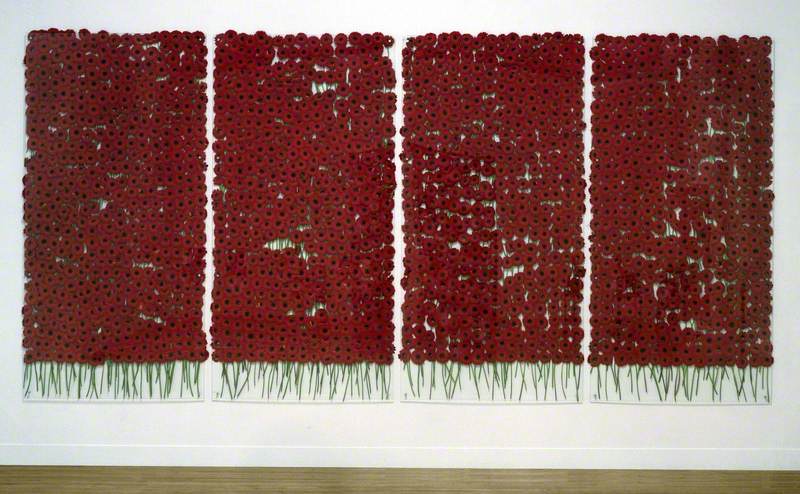

These are the British Empire Panels. Sixteen exquisite, oil-painted boards, each 6.09

Let’s take a closer look at number 11. Brangwyn uses a wide palette, with a range of brilliant indigoes and turquoises, creating a vibrant, exotic portrayal of India. He uses organic brushstrokes and smooth lines to create the pleasing shapes of natural forms, such as the bird in the top right, and the plants which pervade the piece.

The painting is stunning. The bold use of

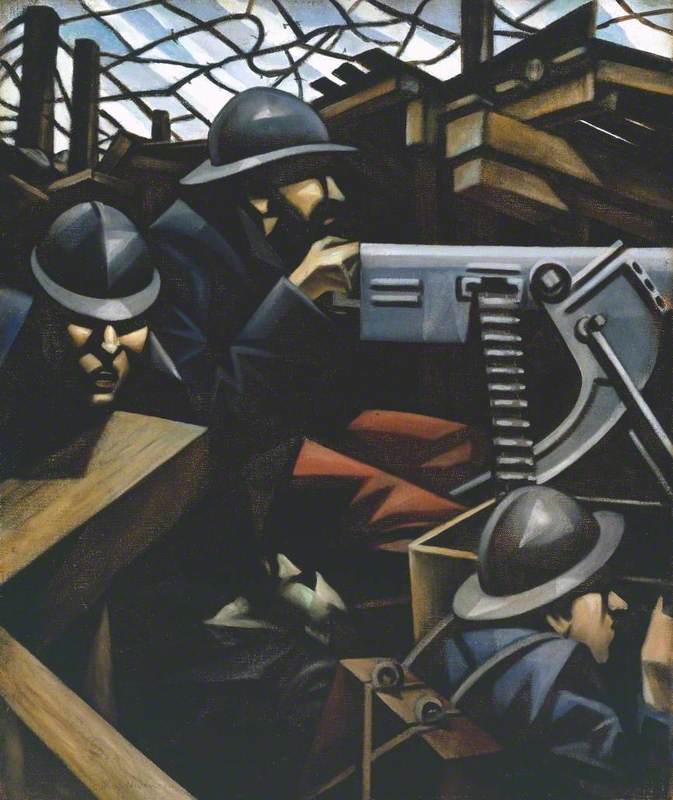

But there is more to the story than meets the eye. In 1926, Lord Iveagh commissioned Brangwyn to paint for the Royal Gallery at the House of Lords, to commemorate those peers who had been killed in the First World War. What Brangwyn painted was two large war paintings, which included images of troops advancing into battle.

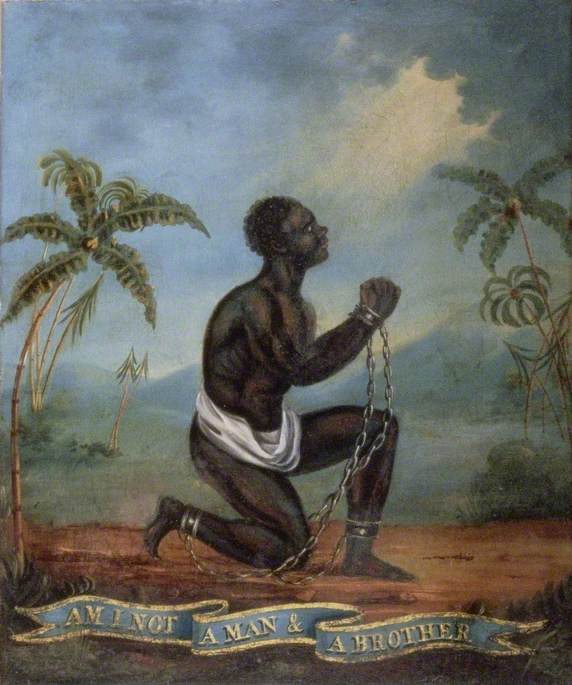

The Lords were unnerved; they found them disturbing and refused. Instead, they asked him to produce a piece celebrating the

Yet again, he was rejected. The Lords declined them, claiming they were 'too

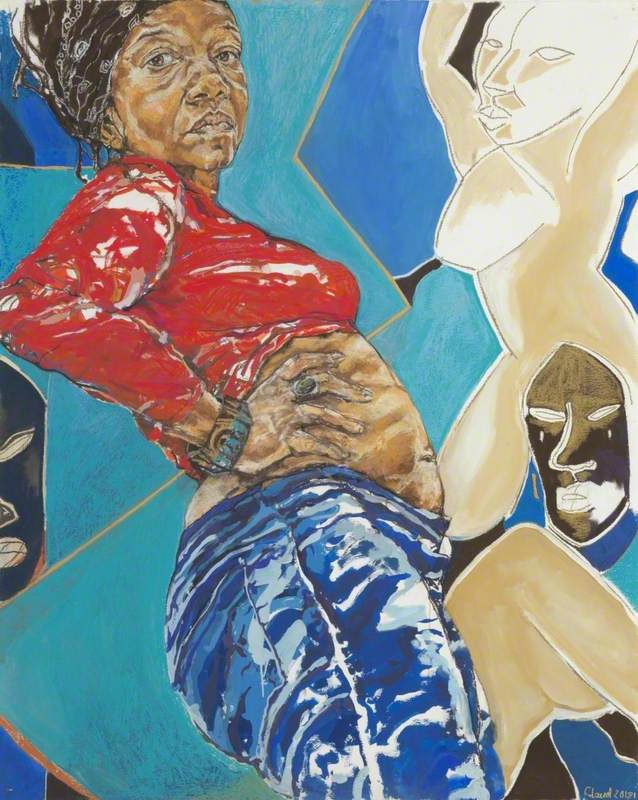

I have a deep affinity for the paintings. Being a British Indian, the British Empire and its effect on the country of my heritage is important to me. I feel a connection with the breathtaking display of culture – the culture that I have witnessed firsthand on my travels to India. The melancholy subtext which lies behind the façade of pomp and glamour is, sadly, another thing which relates to the pain brought by the British Empire.

And it is through art that I have connected with this part of my heritage.

Abhimanyu Gowda