In 1950, the painter John Armstrong (1893–1973) contributed to an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London with some powerful images and equally powerful words. ‘We live in an age of terror’, he wrote in his introduction to ‘Painters’ Progress’. ‘A great deal of the work of our time is in consequence inspired by obsession, cruelty and hysteria… If some aspects of modern art seem to you meaningless that is because the world is becoming meaningless. A painter’s concern is with the world as it is or is becoming, not as you would like it to be.’

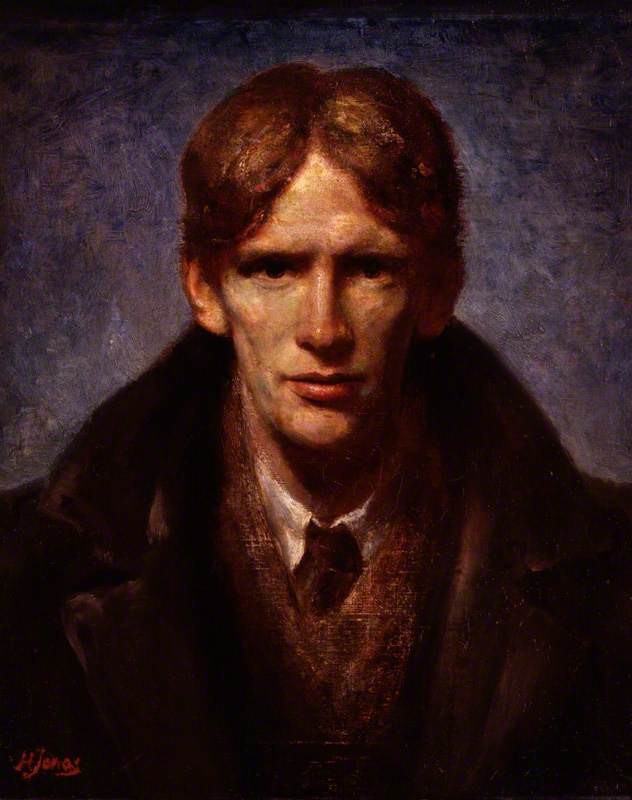

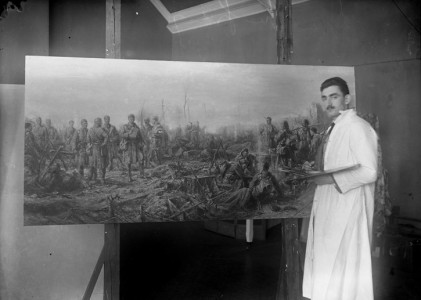

It’s a pessimistic vision, but an understandable one. Armstrong’s career was punctuated by conflict – it coloured his world view and it shaped his art profoundly. Born into a religious family in Hastings in 1893, he enlisted to serve in the First World War before beginning his career. On his return, he set up in London as a theatre designer, muralist and painter, working with artists such as Barbara Hepworth, Paul Nash and Ben Nicholson as they set up the influential modernist group, Unit One. But soon tensions in Europe were stirring again. Armstrong was appalled by the aerial attacks that Franco’s rebels launched against civilians in the Spanish Civil

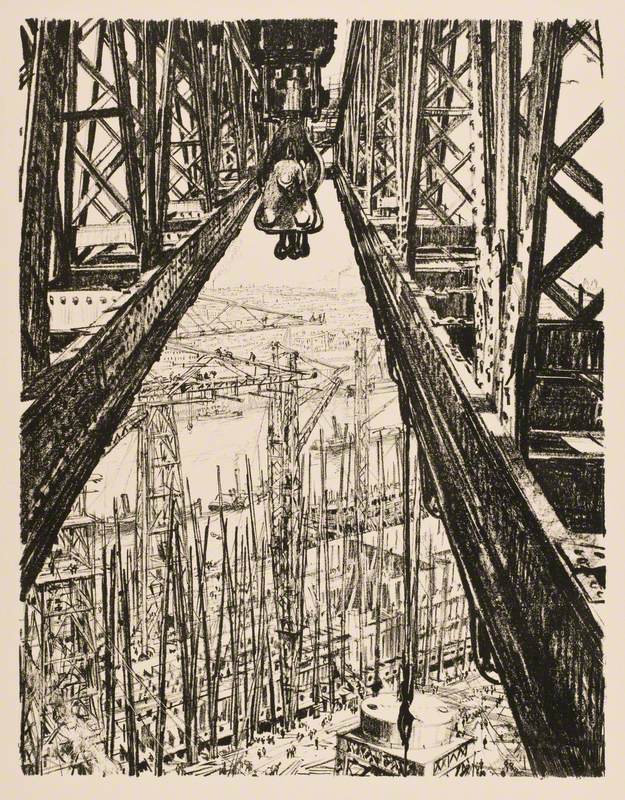

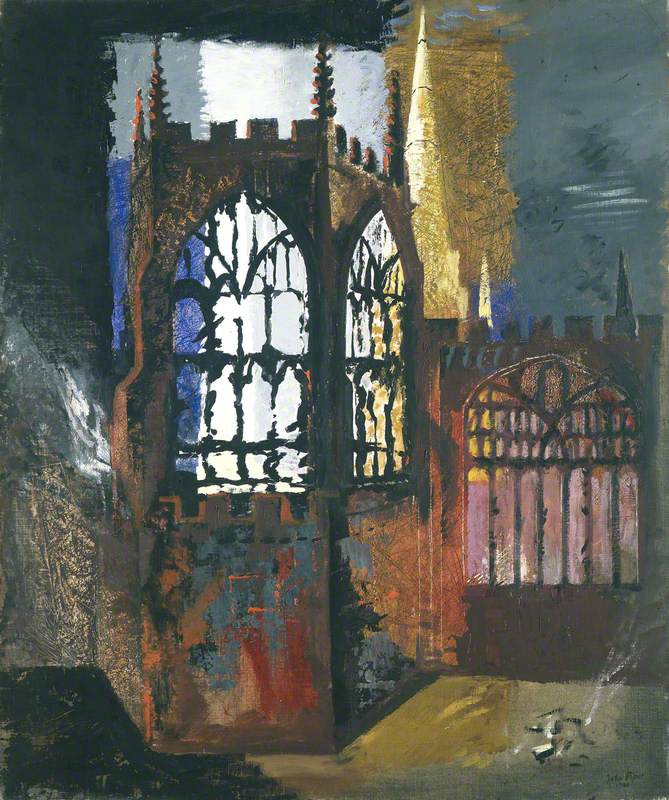

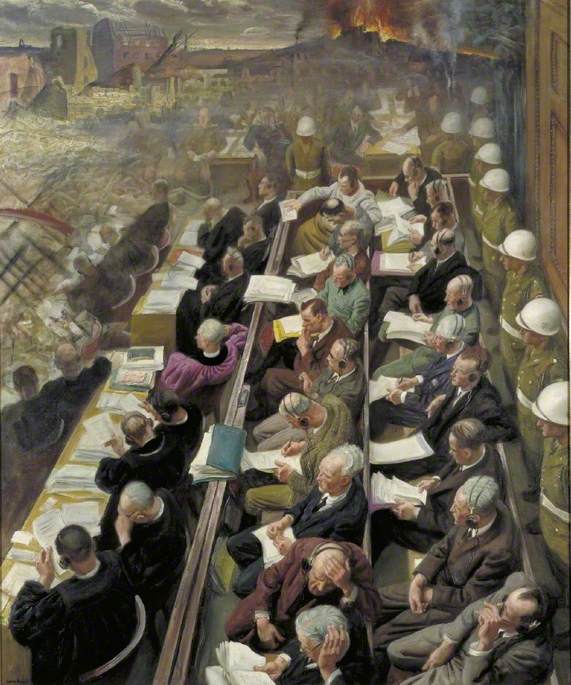

When conflict overtook the continent, he worked as an official war artist in Britain, painting bombed buildings and burnt-out planes. Cold war followed. Armstrong was 51 when the first atom bombs dropped and he died a few months before direct United States involvement ended in Vietnam. Like many of his generation, he felt that, in the course of his lifetime, the veneer of civilisation had slipped.

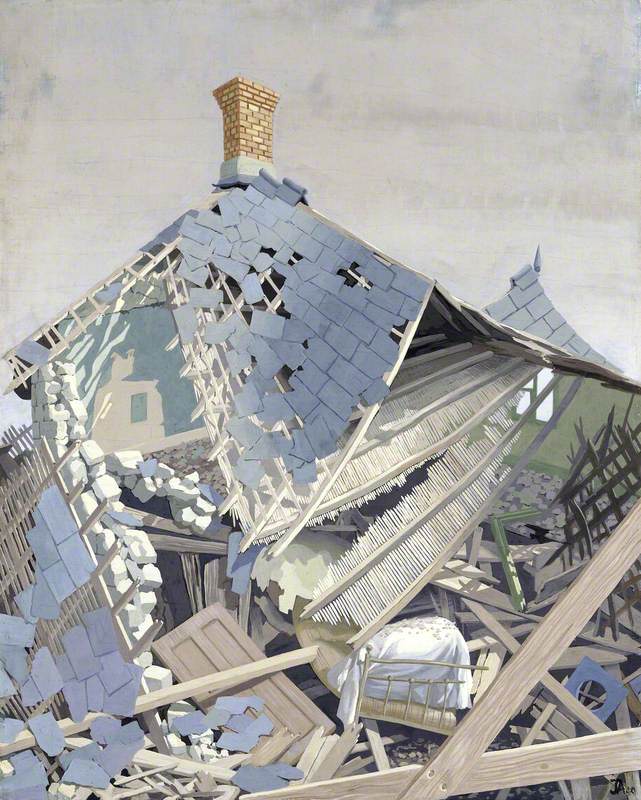

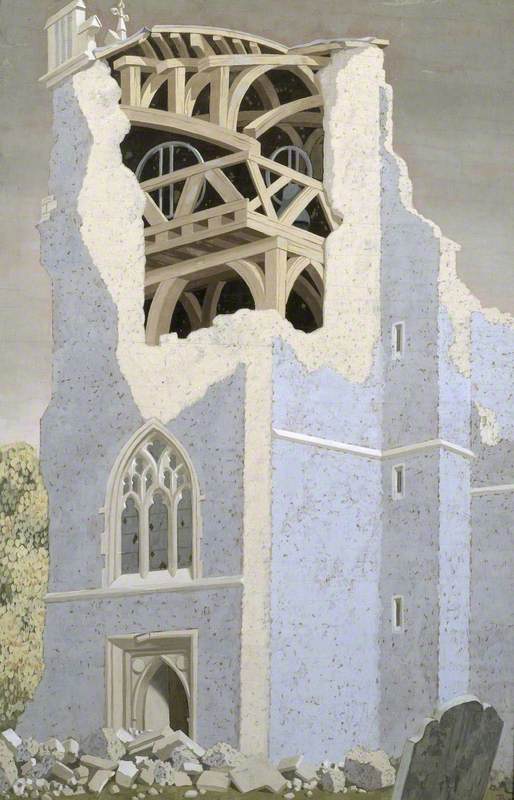

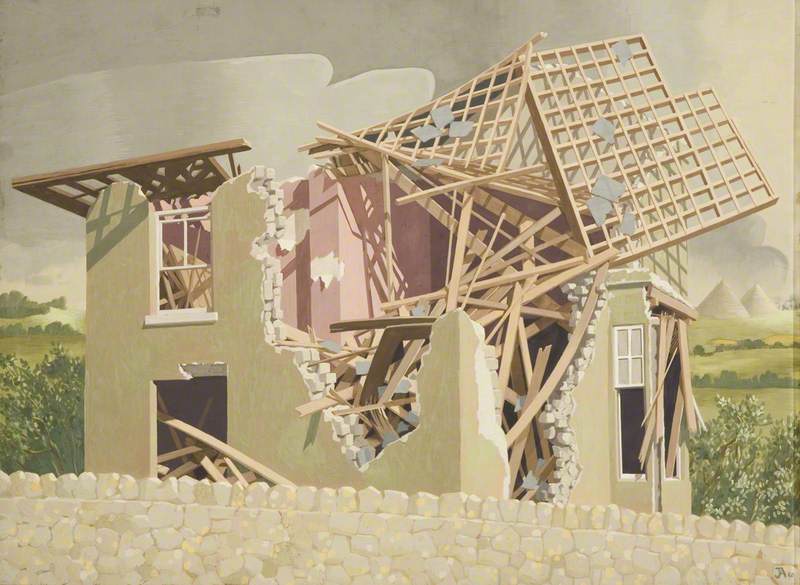

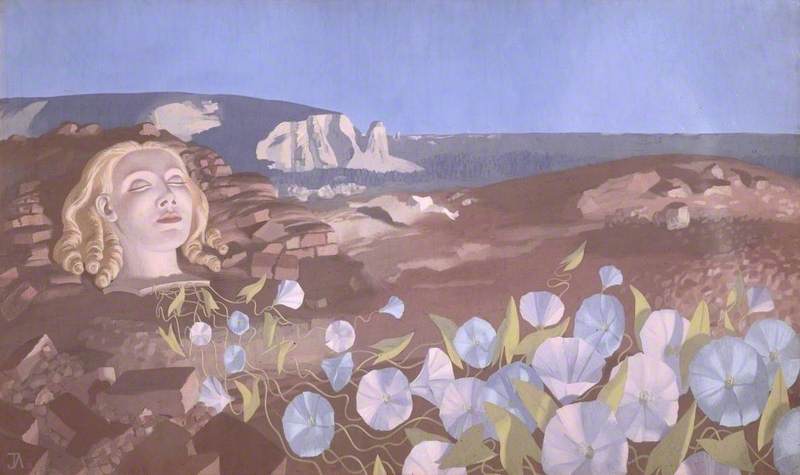

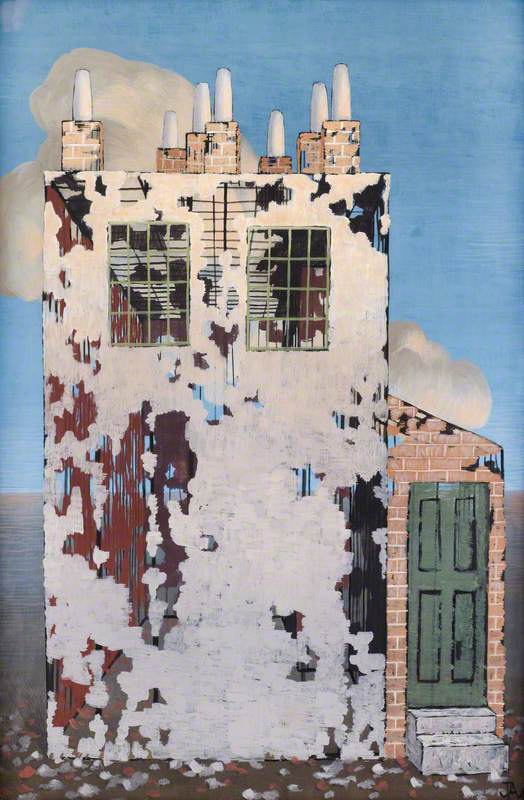

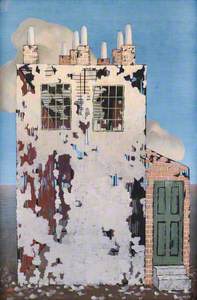

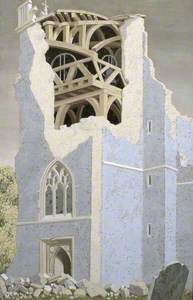

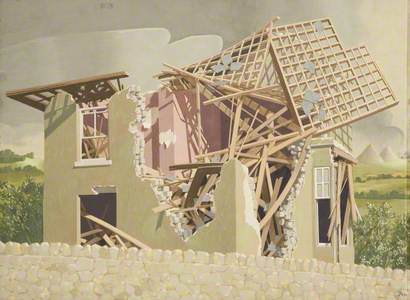

How does this show in his art? Sometimes literally. Among Armstrong’s most striking paintings are those he made of war-damaged houses and churches during the Second World War, their broken walls revealing crumbling foundations and empty, shadowy rooms. Images such as The Villa (1940) are based on real scenes, but they also symbolise the deeper psychological impact of war, which as well as doing physical damage tore up people’s belief in social, political and religious values that had once seemed stable.

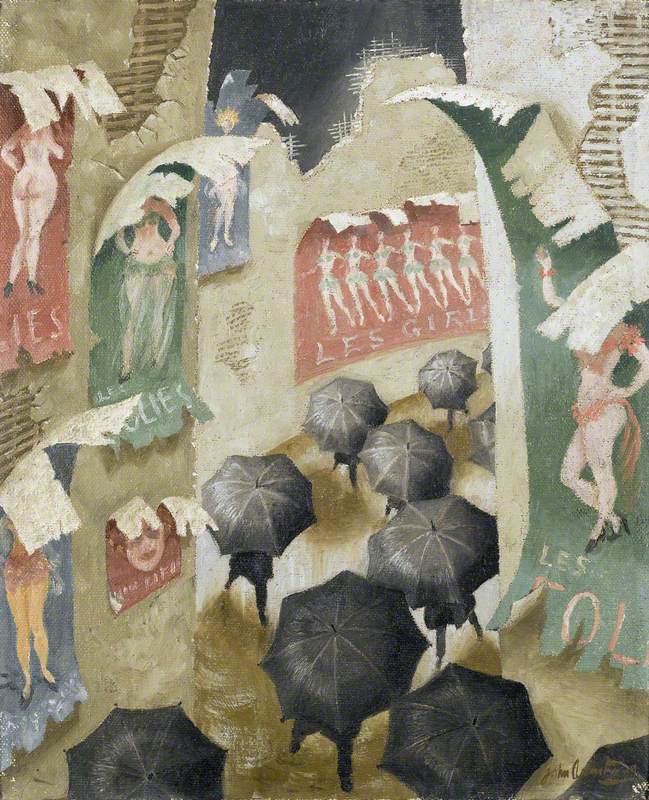

Armstrong repeatedly used this sort of imagery, even in peacetime. His study for The City, painted in 1952, shows suited commuters hurrying down a street, umbrellas up against the wind and rain. At first glance, it seems a familiar enough scene, until you realise that it is not just the posters on the walls that are peeling away, but the walls themselves. As a set designer, Armstrong knew how easily you could put up a front, and how easily it could be pulled down. That sense of fragility, of things being ready to fall apart, pervades much of his art.

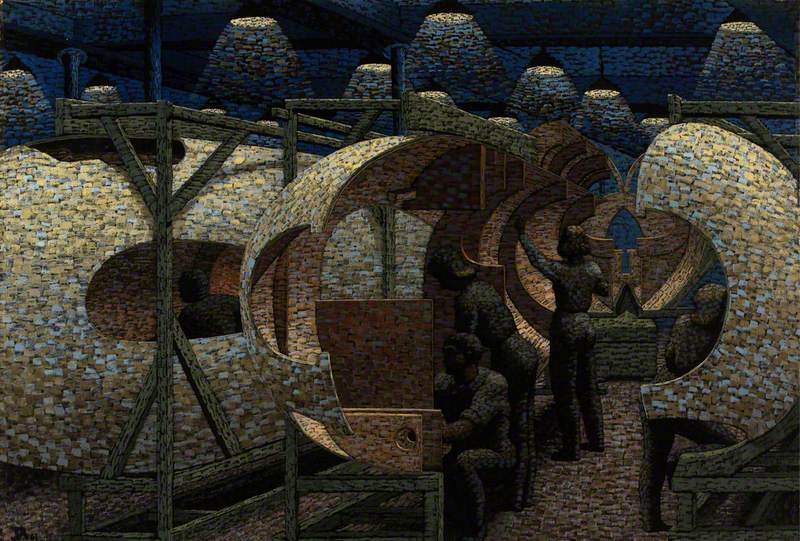

Battle of the Rocking Horse (Study for 'The Battle of Religion')

1953

John Armstrong (1893–1973)

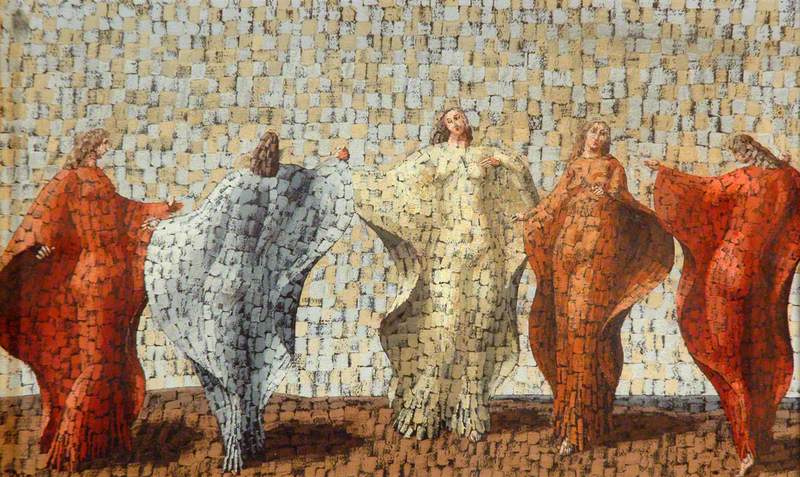

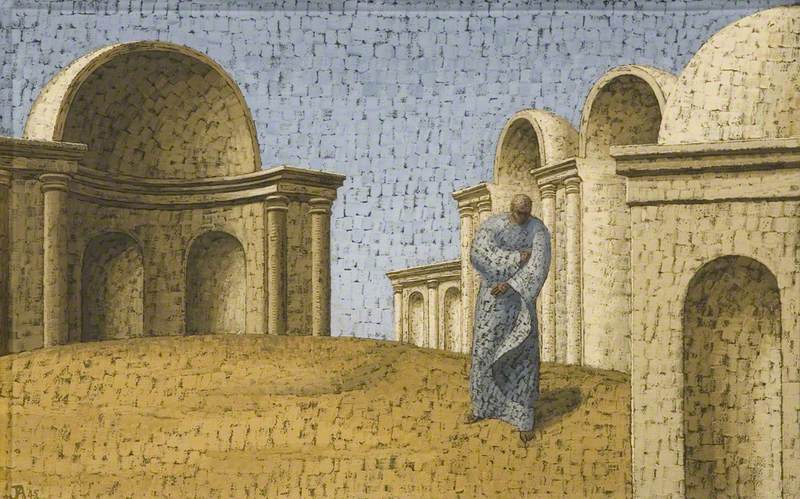

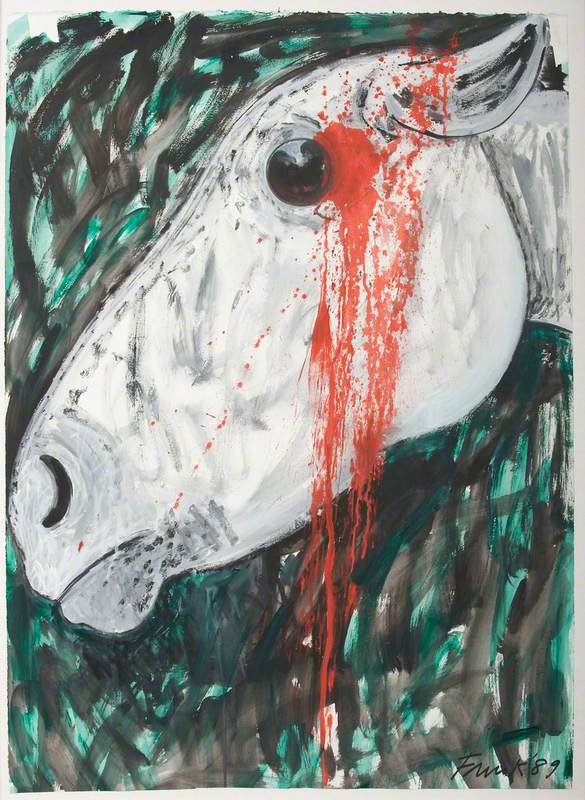

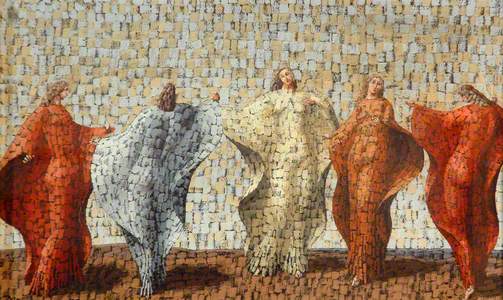

In other paintings, Armstrong took a more obviously symbolic approach. In the 1950s he worked on several absurdist battle scenes showing unhappy clowns and harlequins fighting each other with wooden swords. Pictures such as Battle of the Rocking Horse (1953) are inspired by historical battle paintings by Renaissance artists such as Paolo Uccello (whose famous Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino at the Battle of San Romano is in The National Gallery's collection), but they show up the whole history of noble warfare as a farce. The hapless figures seem none the wiser about who they’re fighting, or for what.

On the occasion of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1958, Armstrong made these thoughts even more explicit. He exhibited an unsettling painting ironically titled Victory in which an

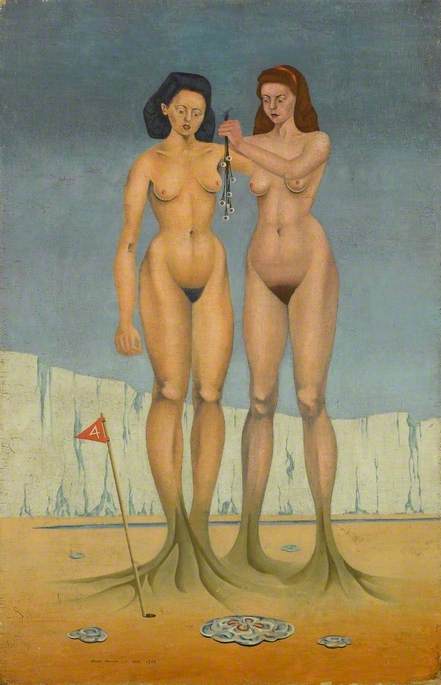

Not all of Armstrong’s paintings focused exclusively or even

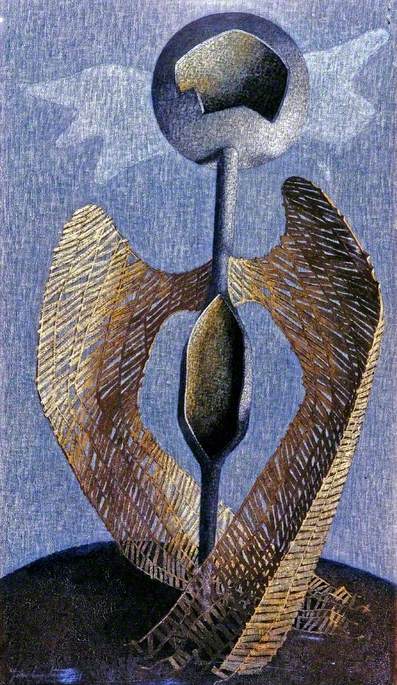

Seemingly innocuous items, like the umbrellas in The City, turn out to have specific meanings – Armstrong explained in 1951 that they ‘symbolise the inadequate beliefs under which men attempt to shelter from the growing storm of despair’. Other seemingly symbolic images are presented with no explanation at all.

Armstrong himself didn’t always know what his pictures meant. In 1938 he explained to an interviewer that ‘I paint usually with my mind half asleep not really knowing what I am trying to do.’ This uncertainty was the point. In a topsy-turvy world, where civilised society seemed ready to descend into anarchy at any moment, art was necessarily unstable too. Armstrong drew on traditional imagery knowing that it didn’t fit the world he lived in. He drew it in a way that made clear it didn’t fit. He spent a career painting civilisation’s veneer while watching it slip.

Maggie Gray, art historian and writer