In Tennyson's poem Idylls of the King, published over two decades from 1859, the poet recounts the story of Vivien and Merlin. Merlin is flattered by the aggressive attention of Vivien – an interloper into King Arthur's court – and eventually he tells her the secret of a spell that leaves its victim 'Closed in the four walls of a hollow tower / From which was no escape for evermore.' As soon as she hears the secret, Vivien works the magic on Merlin:

And in the hollow oak he lay as dead,

And lost to life and use and name and fame.

Then crying 'I have made his glory mine,'

And shrieking out 'O fool!' the harlot leapt

Adown the forest, and the thicket closed

Behind her, and the forest echoed, 'fool.'

Vivien's triumph over Merlin does nothing to either party's credit. For her cunning, Tennyson brands Vivien a 'harlot'; for his gullibility, Merlin is a 'fool'.

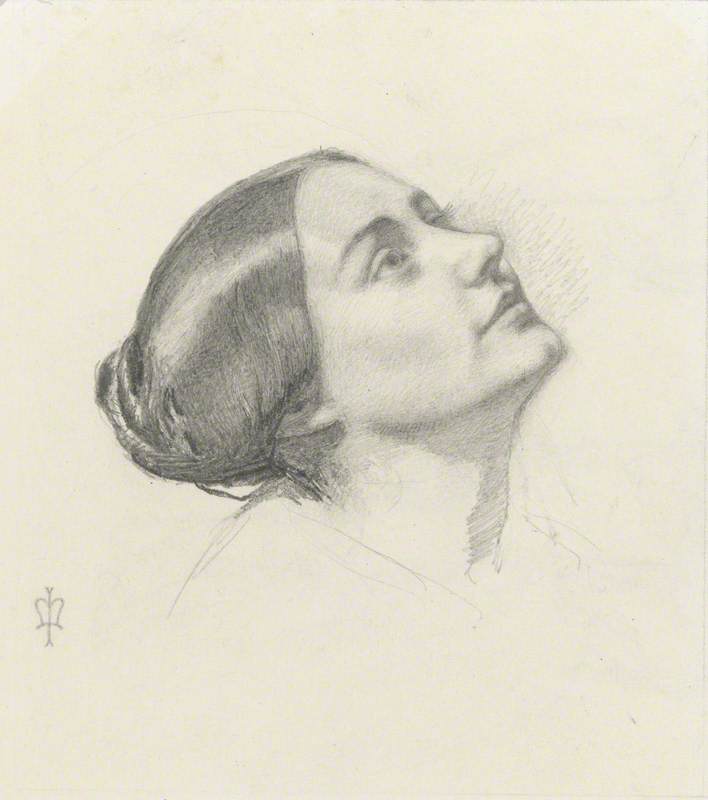

In 1877 Edward Burne-Jones completed his large-scale canvas The Beguiling of Merlin, which depicts Merlin and Vivien (sometimes known as Nimue, the Lady of the Lake) at the moment of betrayal.

Merlin exchanges a look with Vivien, who holds open a book of spells. Vivien's diaphanous robes accentuate the contours of her body; her profile is expressionless. Merlin is exhausted, wilting into the tree's cavity, and the look he gives Vivien is ambiguous: perhaps resentful, or grudgingly respectful?

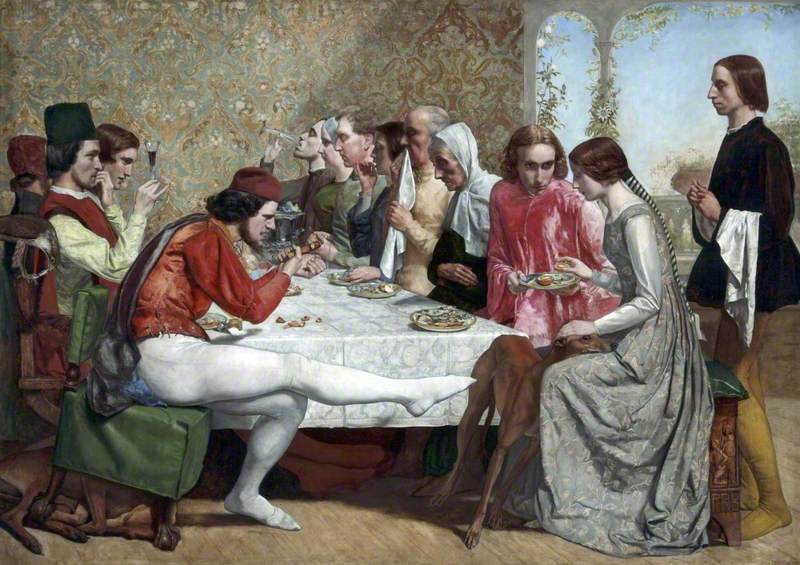

Thomas Marks has written about how Tennyson's poetry inspired a host of responses in the visual arts. The three founding fathers of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, Rossetti, Millais and Holman Hunt, all contributed illustrations to an extravagant edition of Tennyson's poetry that is now held at the British Library ('The Moxon Tennyson').

In the later years of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, artists associated with the movement put the poet at the heart of their artistic practice, painting Tennysonian figures such as The Lady of Shalott and Mariana in sumptuous medieval costumes.

But Burne-Jones' image of a dangerous female enchantress pierces to the heart of a Pre-Raphaelite preoccupation: how to deal with an empowered woman. In particular, a woman who is in control of her sexuality.

This concern has as much to do with the wider context of Victorian society as it does with the particular concerns of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. It is a commonplace (no less true for being one) that ideals of femininity were coming under threat in the second half of the nineteenth century. On the one hand, the burgeoning women's movement was becoming a visible and divisive force. On the other, The Contagious Diseases Act of 1864 focused on the heavy-handed regulation by police of prostitutes, but avoided any inconvenience to their male clients.

This Act became a focus point for campaigners, known as the 'Shrieking Sisterhood' who had their first big political success when they forced the repeal of this Act in 1886. This new generation of vocal and political women were pilloried by the press, and accused of a lack of femininity. In this context, what are we to do with the images of enchantresses, sorcerers and witches that haunt the Pre-Raphaelite imagination? What do these ambivalent representations of powerful women suggest?

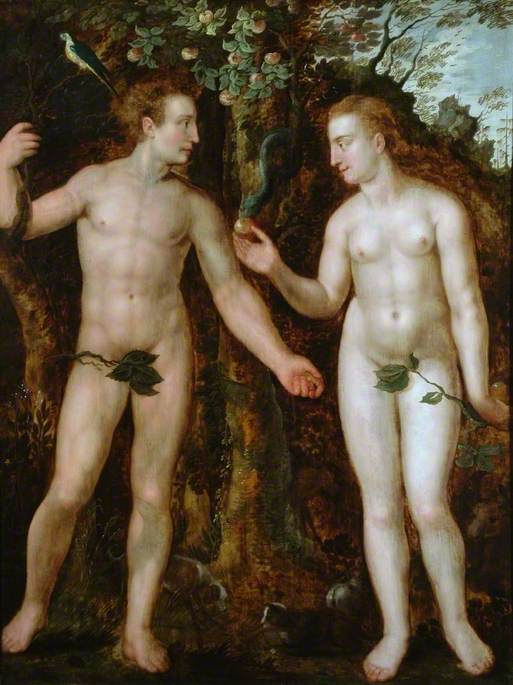

The story of Medea, like the story of Vivien, focuses on a 'deviant' woman. Like Vivien, Medea's story focuses on her betrayal, in her case twice over, of the men to whom she owes her life or advancement in a patriarchal system. The first is her father, who she betrays in order to assist Jason steal a magical golden fleece. The second is Jason, whose affair with another woman drives Medea to avenge herself by killing her and Jason's children. Medea is portrayed several times over by Pre-Raphaelite artists.

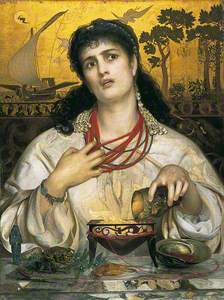

Frederick Sandys' painting Medea, held in Birmingham, depicts a woman surrounded by occult symbols and objects, in the midst of casting a spell.

Medea is represented as a witch: on the table is a magic circle delineated in red thread, enclosing a toad, a flaming potion, berries that look like deadly nightshade, and a shell filled with a viscous substance that evokes blood. Medea clutches at her heavy red necklace, her lips parted and her gaze frenzied; the flames of the potion illuminate her chest. The image is powerful, demented and deliberately evil.

Frederick Sandys was reputedly interested in the idea of 'beautiful but destructive women', as the label for Sandys' painting Queen Eleanor relates in the Cardiff Museum.

Queen Eleanor (c.1122–1204)

1858

Frederick Sandys (1829–1904)

In this painting Eleanor creeps through undergrowth, holding a red thread that will guide her to the secret home of Rosamund Clifford, the mistress of Eleanor's husband, King Henry II. Eleanor holds a dagger in one hand and a cup of poison in the other – reputedly the choice of death that she offered to Rosamund on discovering her.

Two decades later, Val Prinsep, a close friend of Burne-Jones and John Everett Millais, painted his own version of Medea titled, Medea the Sorceress.

True to the tenets of the Pre-Raphaelites, whose style had been firmly established by this point, Medea kneels in naturalistic scenery. It is late evening; the sunlight turns the tree trunks gold and illuminates the scales of a snake. Medea is in the centre of the canvas, leaning behind her to place a mushroom in a basket and holding a long dagger in her right hand.

Unlike Sandys' paintings of women, Prinsep's Medea is ambiguously characterised. Like Burne-Jones' Vivien, Medea's face is in profile, which largely masks her expression. And as with The Beguiling of Merlin it is this ambivalence, this inability to know what a powerful woman is thinking which seems to carry the narrative weight of the painting, and which is a key factor in the painters' depiction of the uncanny.

The subject of a woman as femme fatale also appears again in Waterhouse's trio of paintings on the subject of Circe, a legendary witch who transformed men into animals and kept them as slaves. Not all the paintings are in the UK's national collection – Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses (1891) is in the collection of Gallery Oldham, while Circe Individiosa (1892) is now in the Art Gallery of South Australia, and The Sorceress (1915) is now in a private collection.

The idea of women as disruptive forces recurred in Pre-Raphaelite painting. The artists were interested in the straightforward depiction of female evil or of ambivalent, unknowable strong women. 'Woman as witch' was a powerful metaphor enclosing a range of societal concerns about empowered women.

Victoria Ibbett, writer

Further reading

Judith R. Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London, University of Chicago Press, 1992

Deanna Petherbridge, Witches and Wicked Bodies, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, 2013