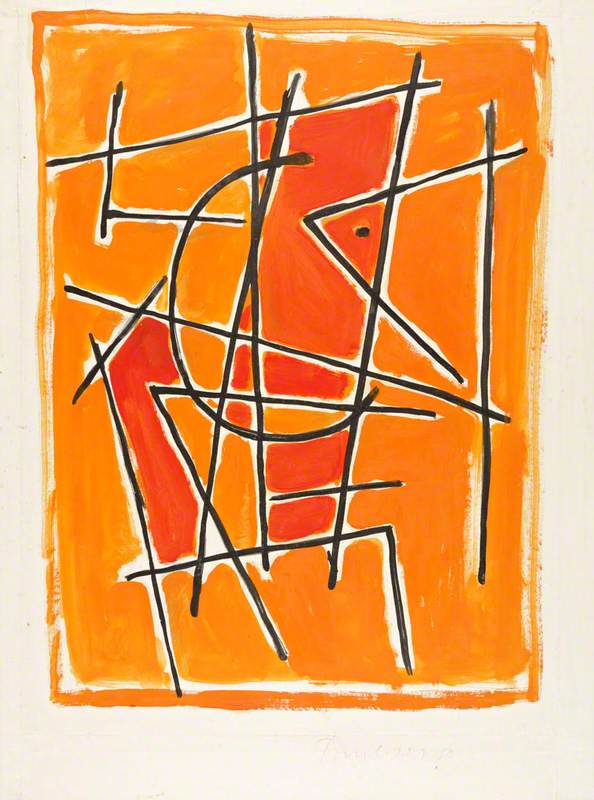

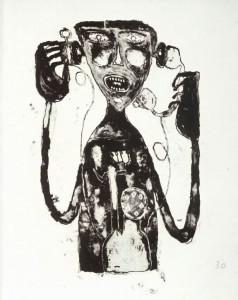

William Turnbull was born in Dundee on 11th January 1922. His artistic talent shone through early on, especially when working in the illustration department of the publisher D.C. Thomson, known for children's comics such as The Beano and The Dandy. The knowledge he gained during his three years there would remain with him for the rest of his life, helping him to articulate and simplify form in clear and radical ways.

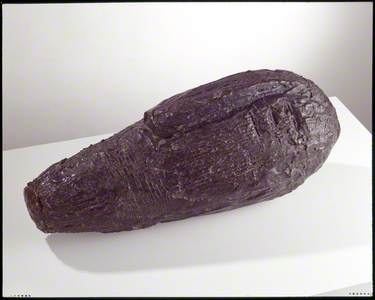

He was also inspired by modern artists' radical approaches to figuration – and particularly artists such as Picasso, Miró and Dubuffet. Their reformulations of the human face and body drew actively upon the diverse anatomies found in the caricatures and cartoons of illustrated magazines. Turnbull himself had already learned about this visual culture first hand while working as an illustrator.

Following this, Turnbull spent five years in the Royal Air Force. The experience of flying during the Second World War had a huge effect on how he saw the world and on how he made art. The aerial experience was profound and the cockpit of an airplane offered new and intense views, informing his subsequent conceptualisation of the landscape. As he recalled in 2011: 'I was up there and there was nothing else... it made you think about space as a thing, almost an object.'

The world looks very different at 30,000 feet. For Turnbull, this perspective provided different ways of thinking about people and places, about lines of descent and ascent, about verticality and horizontality.

Turnbull's grasp of such things was also very different to other sculptor-painters working in Britain who also had flying experience both during and immediately after the war.

Michael Ayrton, for example, turned to the figure of Icarus in the 1950s to narrativise symbolic ideas around flight. And the artist David Annesley translated the experience of aerobatics as a trainee pilot into the curvilinear forms of his abstract sculpture.

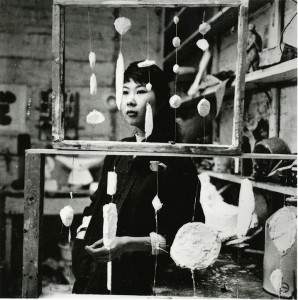

Working in the RAF brought much international travel and Turnbull developed a long-standing interest in East Asia and its ancient cultures. This was much enhanced by his subsequent travels with his wife, the Singaporean-British sculptor Kim Lim.

As is often the way with artists who have travelled a lot early on in their lives, Turnbull always had an eye and mind for human commonalities and shared cultural concerns. He was fascinated by images and objects that could cross time and place, and speak to many people whatever their backgrounds.

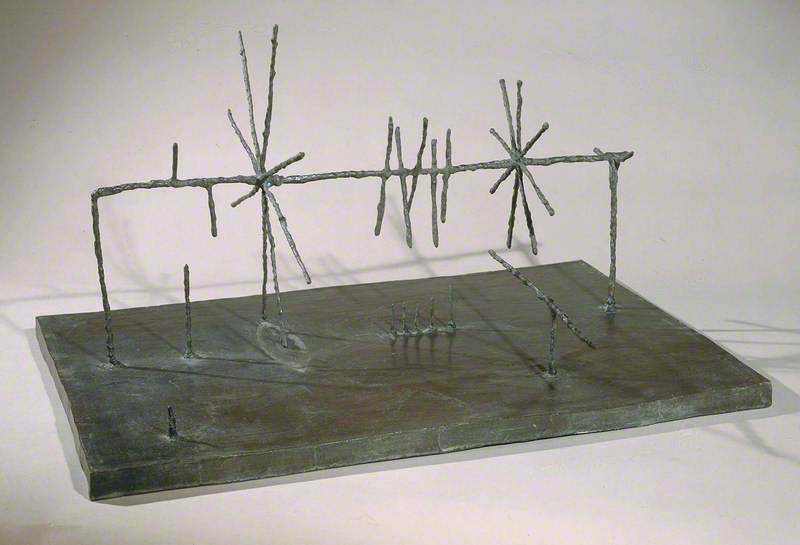

Looking back today, in his centenary year, we might reflect upon such early experiences in relation to the broader concerns of his work – and to his artistic achievements more generally. His early success was notable, coming on the back of his time in Paris (after the Slade School of Art) in the late 1940s, where he met artists such as Constantin Brâncuși and Alberto Giacometti.

In 1952 he participated in the now-famous 'Aspects of British Sculpture' exhibition at the British Pavilion in the Venice Biennale, and in 1956, he showed his work in 'This is Tomorrow' at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. But there is much more to learn about Turnbull and his work from this decade onwards – through the geometries of steel and colour in the 1960s and 1970s, to the return to figuration from the later 1970s onwards. He died in 2012, making working into the early 2000s.

Perhaps, most importantly, we might reflect upon the fact that Turnbull was a painter as well as sculptor. This is still not fully reflected in the collections that include his work. His lifelong interest in sculpture and painting shows him as one who engaged actively with the concerns of artists in Europe and North America, as well as Britain.

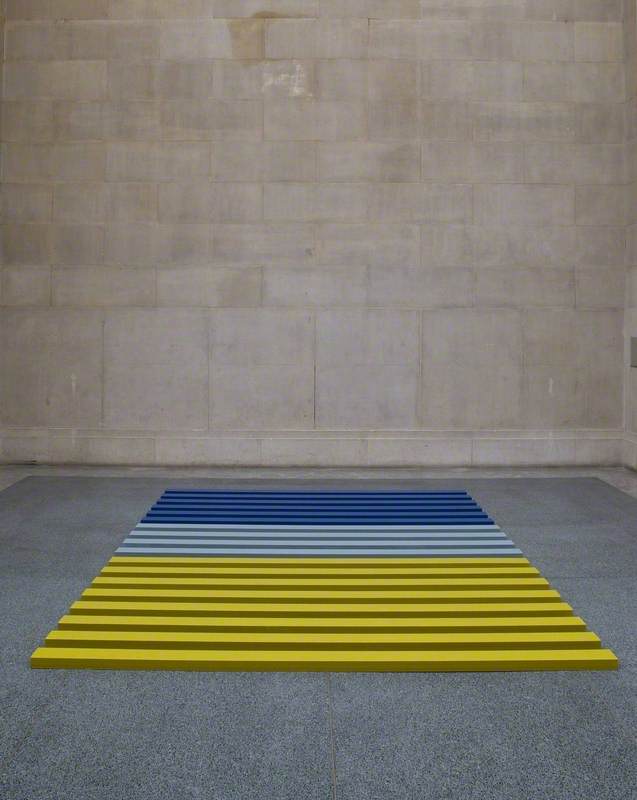

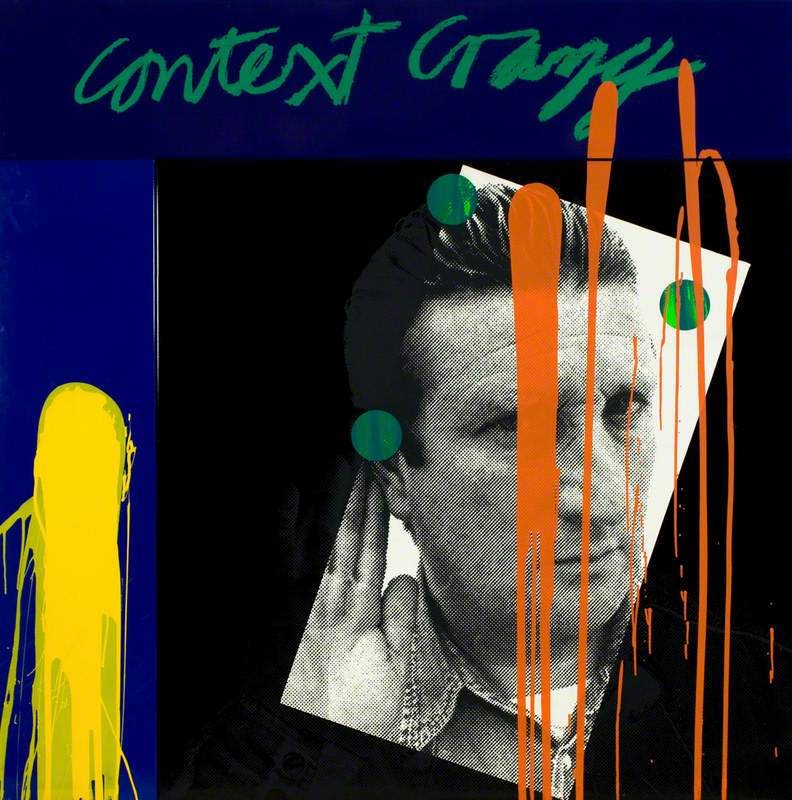

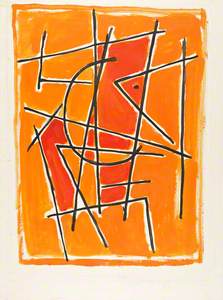

Turnbull first travelled to North America in 1957 and was increasingly in contact with its artists, including Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Helen Frankenthaler. Exchanges were important and these were friendships that lasted for many years. Turnbull loved the ambition and newness of American painting and the innovative sculpture of this time – with its bold and unabashed deployment of expansive colour and its use of industrial materials.

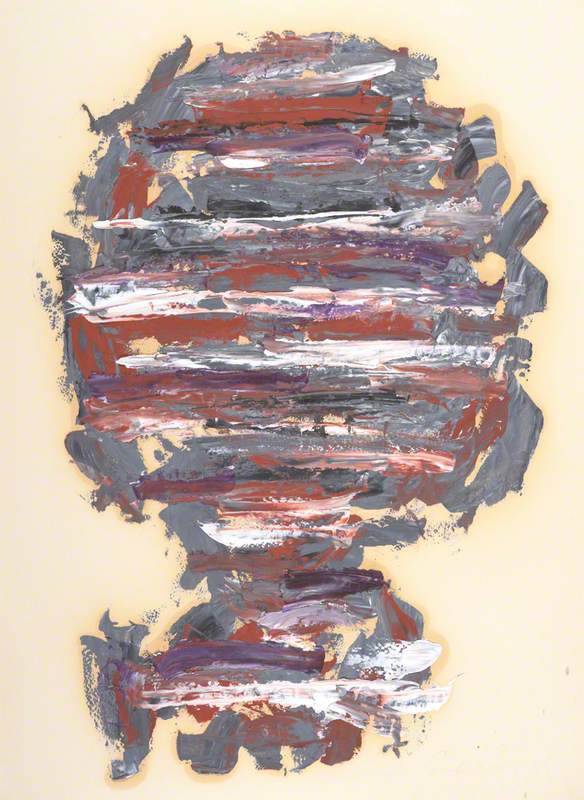

He took up such concerns with a passion and made them his own, creating some of the boldest and most extraordinary paintings made in Britain across these decades. A number were shown in his retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1973. His paintings in the 1960s and 1970s became much larger, as he set about creating colour fields that could immerse viewers and draw them into the direct, one-to-one experiences of the work.

In 1963, at the age of 41, Turnbull stressed what he called the importance of 'physical scale directly related to the observer'. This became increasingly important to him and we find large, unframed paintings that work as environments as much as images.

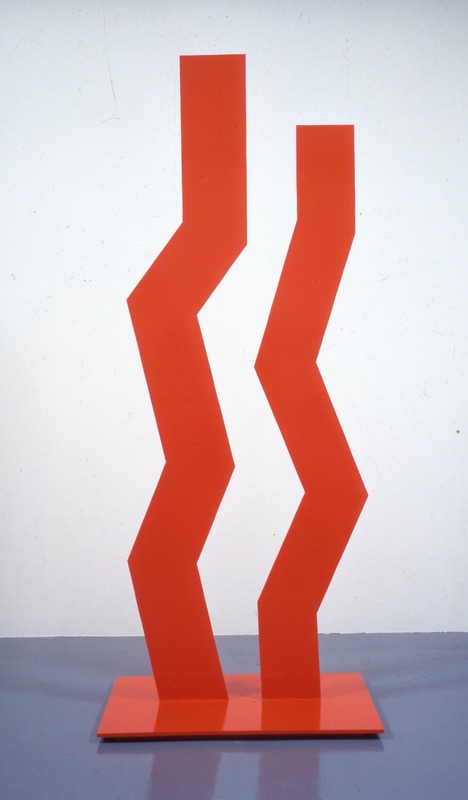

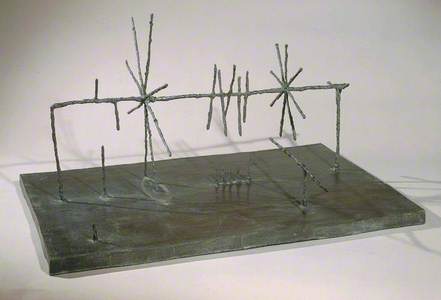

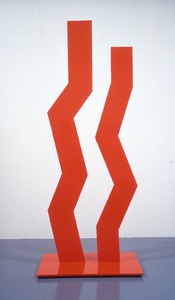

In his sculpture of this period, Turnbull turned to industrial and synthetic materials. This marked a significant departure from the materials and processes of the 1950s. We now find Turnbull exchanging modelling for welding, as clay and plaster are exchanged for steel, aluminium, fibreglass and acrylic.

Geometry also played an increasingly important role as Turnbull constructed sculptures out of preformatted sheet metal, working with rectangles, tubes and increased linearity. Turnbull carefully treated the surfaces of his unpainted steel sculptures. Bold colour also played an important role, as many of his steel sculptures were painted – often in gloss or metallic paint.

Across the works from these years, we also see constant interest in combinations and permutations – with elements of a work being able to be moved and compositions altered. Again, the viewer's role as an active participant in the work interested him, developing ideas that we can also see in his sculpture of the late 1940s, some of which contained movable parts.

Although Turnbull's sculptures and paintings were two separate strands of his practice, there was much cross-fertilisation and he increasingly enjoyed displaying them together. He was, you might say, an object maker who made both sculptures and paintings.

Looking back at his sculpture and painting in 2011, Turnbull reflected their commonality and togetherness in interesting ways. He reflected: 'I was very much concerned that a sculpture was an object and a painting was an object. The paintings I made were objects, they weren't illusions. They didn't refer to something else, they only refer to themselves, and so they were actually in the same area but they were made with different stuff.'

Such words were to be heard in a fascinating film about the artist, Beyond Time: William Turnbull, made by the artist's son, Alex Turnbull, in collaboration with Pete Stern. Released in 2011 after five years of production, it includes rare footage and testimonial accounts relating to his life and work.

Jon Wood, writer, curator and editor of William Turnbull: International Modern Artist published by Lund Humphries, 2022