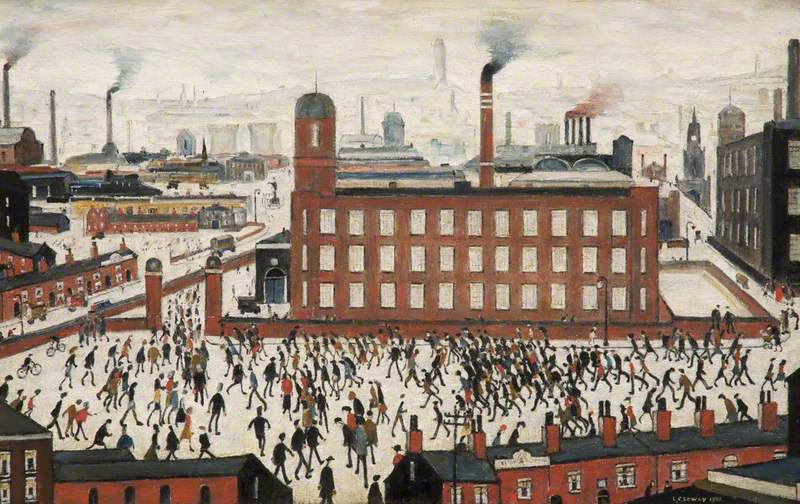

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Oldham was a town feeling the effects of the north-west of England’s Industrial Revolution. What had been a town of 12,000 inhabitants in 1800 had grown tenfold to house 137,000 residents in 1900. By 1870 the town could lay claim to the fact that it was home to the most cotton spindles in the world. It was against this backdrop that Abraham Stott and Elizabeth Stott’s fourth surviving child, William, was born in 1857.

We know from the censuses that at the time of William’s birth Abraham Stott was a dyer and cotton waste dealer. By 1871 he is listed as cotton spinner, proprietor of Abraham Stott & Sons. William had three elder brothers who were to follow their father into the family business, relieving some pressure from William and leaving him free to follow his artistic ambitions.

In his 1894 article 'The Studio', the critic R. A. Stevenson states that he met Stott 'in 1879 when he landed in France without any training except the English stippling in chalk which he was bound to forget at the Beaux Arts.' This is either a case of not letting the facts ruin a good tale, or a symptom of the general disregard in which the regional art schools were held. Stott had in fact enrolled at Oldham Art School in 1875 or 1876. There he studied under established Oldham artist John Houghton Hague until the art school closed in 1878, at which point he transferred to Manchester Art School, alongside other local artists G. H. Wimpenny and F. W. Jackson.

In 1878 Stott moved to Paris to further his studies, under Jean-Léon Gérôme. His acceptance by the Parisian art establishment seems to have been rapid, Girl Knitting and Daydream were shown at the Paris Salon in 1881 and in 1882 he was awarded a medal from the Salon for Le Passeur. Le Passeur also proved popular on the other side of the channel, being shown at The Fine Art Society later the same year.

The year 1882 also saw Stott marry doctor’s daughter Christina Mary Bradbury in Shaw Church, Oldham. They spent their honeymoon in Scotland, staying some of the time with John Forbes White, the Aberdeen collector, who was part of a group of wealthy art patrons who founded Aberdeen Art Gallery. He then returned with Christina to Ravenglass in Cumbria, where he rented a house and studio. His main residence and studio was in London, which formed a base from which he continued to make trips to France.

In the early 1880s, William Stott had added 'of Oldham' to his name after people began to confuse him with Edward Stott, who hailed from nearby Rochdale, and whose full name was coincidentally 'William Edward Stott'. Edward Stott had been born two years later than William, and was also moving between France and England around that time.

Stott was a long-time follower of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and several of his paintings show very clearly the influence of the older American painter. In 1886, Whistler and his partner Maud Franklin came to stay with William and Christina in Ravenglass. The following year Franklin modelled for Stott in his painting, Venus Born of the Sea Foam, which got completely panned by the critics and was the cause of a permanent breakdown in the relationship between Whistler and Stott. Accounts vary as to who did what to whom (as is often the way with these things!) but there was certainly a scuffle at the Hamilton Club in London in March 1889.

Stott was extremely angry with Whistler for having left Maud to go and marry Beatrice Godwin the previous August, while Whistler had not got over the Venus painting and fact that his partner of the time had been prepared to fully undress for Stott, in at least one sense. Whistler’s widely shared version was that he was able to land a kick on Stott’s buttocks, although Stott claimed that he (Stott) had actually set about Whistler with some success. Whistler was undoubtedly better connected and more influential than Stott – he would definitely have had a massive social media following if he was alive today – so his version is the one which is usually told.

Despite showing regularly in London, Stott never seemed to be fully accepted by the art establishment on this side of the channel. He showed at the Royal Academy but was never invited to be a member. His early death at the age of 42 leaves us guessing as to how his career might have progressed had he lived longer. While the critical reaction to his work was often mixed, his work was shown often in galleries and appeared to be popular among the public and fellow artists alike. In an 1896 review in The Speaker, his friend, the artist Walter Sickert, said, 'Mr Stott has never had justice done to him. He is a great painter, and great painters are rare.'

Rebecca Hill, Exhibitions and Collections Coordinator (Art), Gallery Oldham

The exhibition ‘William Stott of Oldham: Great Painters Are Rare’ will open at Gallery Oldham on 26th January 2019.

Stott’s painting Le