Very few artists have captured the subtle contours of the Sussex Downs as well as Sir William Nicholson (1872–1949) whose 150th anniversary is celebrated by two exhibitions in the county this year.

A series of small oil sketches he made while living in the village of Rottingdean, on the outskirts of Brighton, from 1909 to 1914 are masterpieces of understatement.

The Windmill, Brighton Downs (Brighton Downs, Rottingdean)

1910

William Nicholson (1872–1949)

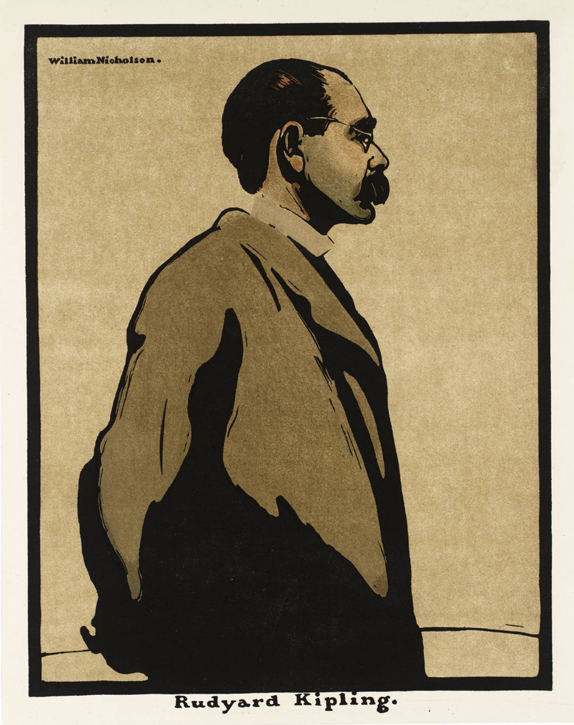

Nicholson strode across Kipling's 'blunt, bow-headed, whale-backed Downs' in the company of the writer himself when he visited him at his house in the village in 1897 for a portrait.

It's a fine example of his graphic art and probably the most striking image of the writer who in some portraits looks more like a mid-level bureaucrat than a literary genius. By taking a viewpoint from below and capturing him in contemplative profile, Nicholson manages to suggest the great man's imaginative scope.

Nicholson himself was the subject of a telling portrait in 1909, the year he moved to Rottingdean. Augustus John (1878–1961) recognised his fellow artist as something of a dandy with his cane, gloves and immaculately polished shoes.

Nicholson installed his family at the vicarage in Rottingdean, which he renamed the Grange, where, until the end of this month (July 2022), there is an exhibition of his work.

The Grange, Rottingdean

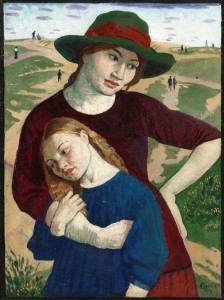

As well as a small selection of paintings and prints, some of Nicholson's clothes, props and equipment are on display, including his woodcutting tools. By the time the artist and his first wife Mabel moved to the village they had four children – Ben, Christopher, Nancy and Tony – all of whom feature in a group portrait painted by William Orpen (1878–1931) two years earlier.

Ben, the eldest, seated right, became an artist who in some ways overshadowed his father; Tony, seated next to Ben, died in the First World War; Nancy, wearing white, married the writer Robert Graves and Christopher (Kit), in a purple dress, died at the age of 44 after a gliding accident. Their mother Mabel, standing at the back, was a victim of the 1918 flu epidemic.

But, in those carefree, pre-war days at the Grange the family enjoyed walking on the Downs and playing on the beach beneath the cliffs, a short distance from their house.

While Nicholson painted his Sussex scenes on the spot, usually on small panels, he was also showing his versatility in a series of exquisite still-lifes for which he is, perhaps, better known. The Lustre Bowl with Green Peas, was painted a year after Cliffs at Rottingdean. The bowl is an earthenware pot with a platinum-lustre glaze which, unlike silver, doesn't tarnish. The combination of superb technique and spare composition is characteristic of his best work.

Nicholson was able to live in some style in Rottingdean thanks, in part, to his portrait commissions and graphic work. His 1901 portrait of William Henley (1849–1903), a poet, critic and dramatist, was his first formal portrait commission paid for by friends of the writer.

Henley was a combative character who had lost a leg and was the model for Robert Louis Stevenson's Long John Silver.

He was also instrumental in launching Nicholson's career, having agreed to publish the artist's woodcut of Queen Victoria in the New Review which he edited. The less-than-flattering image, dating from 1897, marked the 60th anniversary of the Queen's accession to the throne and was the first of many commissions from Henley.

Queen Victoria (1819–1901)

1897

William Nicholson (1872–1949)

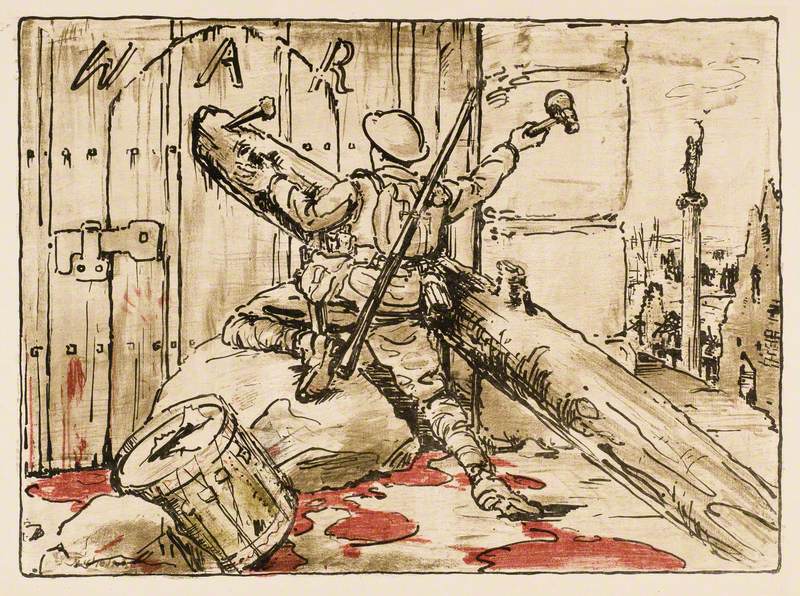

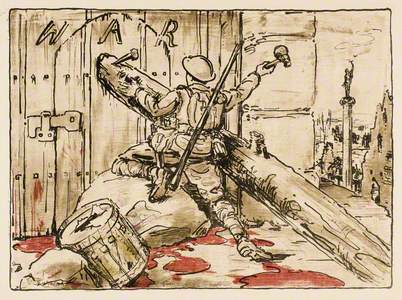

Much of Nicholson's most successful graphic work dates from the late 1890s including An Alphabet, Twelve Sports and London Types and Portraits. An exception is The End of War, which was commissioned by the Government's propaganda department in 1917 when, after three years of fighting and the loss of half a million British soldiers, it was considered vital to maintain public support for the war in France.

Nicholson's image of a soldier hammering shut a door leading to war, with pools of blood in the foreground, carried the message that sacrifice can be justified by victory and lasting peace.

Following the loss of his son Tony and his wife Mabel in 1918, Nicholson swiftly remarried. Edie Stuart-Wortley, whose husband Jack had been killed in the war, was 18 years his junior and had been closer to Ben Nicholson, who was said to have been in love with her.

The marriage further contributed to the uneasy relationship between father and son while William's daughter Nancy refused to attend the wedding.

Ben's portrait of Edie in 1917 is uncharacteristic of the work of an artist who was at the forefront of modernism. Later summarising his father's career he said, somewhat dismissively, 'he merely wanted to paint.'

William returned to Rottingdean in 1920 when, for three years, he, Edie and their new baby Elizabeth lived in North End House, the former home of the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) who designed stained glass windows for the village church.

North End House, Rottingdean

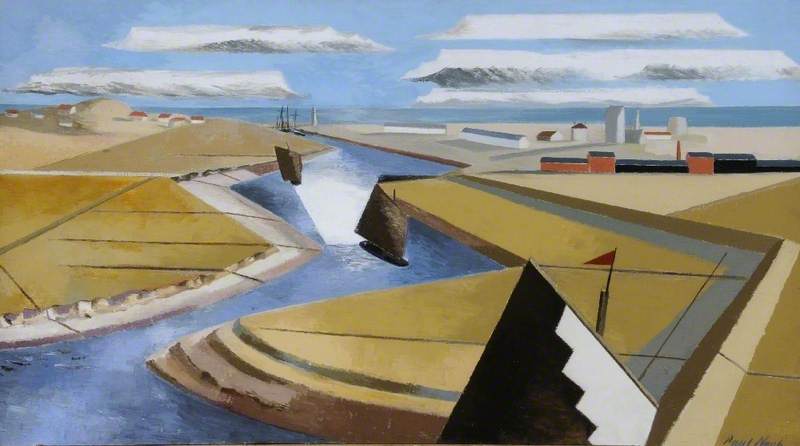

Between the wars, many artists were inspired by the Sussex landscape including Eric Ravilious (1903–1942), whose watercolours of the county provide an interesting contrast to Nicholson's oil sketches. Both will be represented at an exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. Called 'Sussex Landscape: Chalk, Wood and Water', it runs from 12th November 2022 until 23rd April 2023.

Curiously both Ravilious and Nicholson, at very different times, had an affair with an artist called Diana Low (1911–1975) who had been a pupil of Nicholson and produced a portrait of him in old age.

In an interview recorded for the British Library twenty years ago, the artist Humphrey Spender (1910–2005), who had been married to Diana Low's sister, described how Nicholson, then around 60, was friends with the parents of Diana who was about 18 – 'really great friends, to the extent that their young and very pretty daughter was told there was nothing better for her than to go and have lessons in painting from William Nicholson. I need hardly go on, need I?'

Much more lasting than that brief liaison are Nicholson's sketches of Sussex. My favourite is Judd's Farm, now covered by the urban sprawl of Peacehaven.

Not given to theorising, it was one of the few paintings that Nicholson spoke about. 'You may note,' he said, 'that the horizon divides the panel into nearly equal parts; an odd place to find it but the pattern manages to adjust it all right. The colours – few, but inevitable; my subject – so simple that I could finish it in my head before releasing the paint.'

Only an artist of rare, natural talent could say such a thing.

James Trollope, writer and columnist

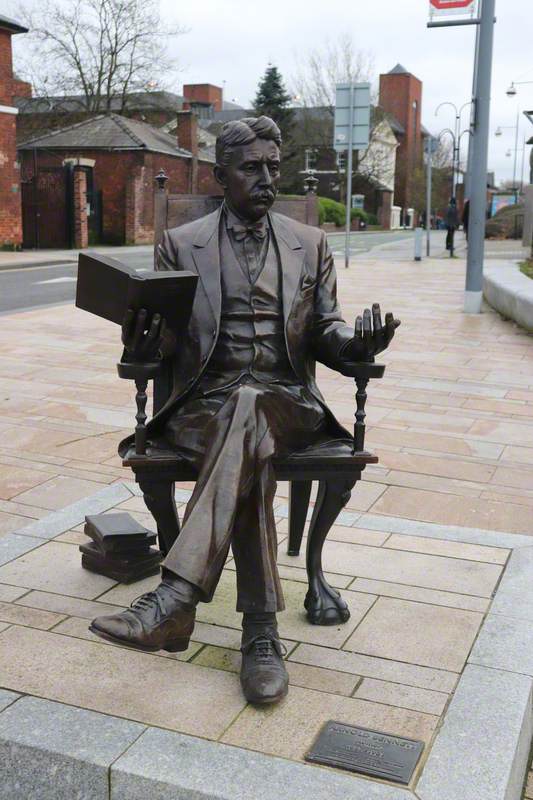

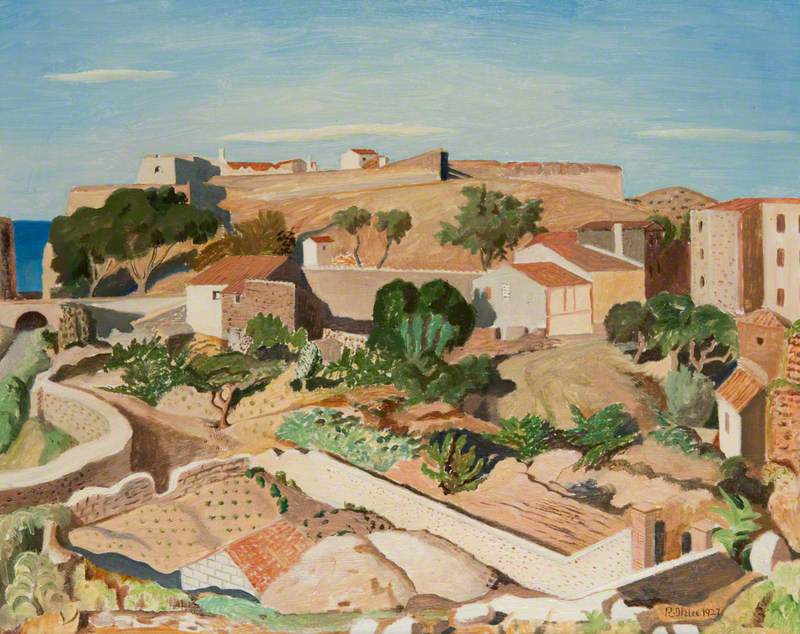

James's latest book Rudolph Ihlee: The Road to Collioure is now widely available