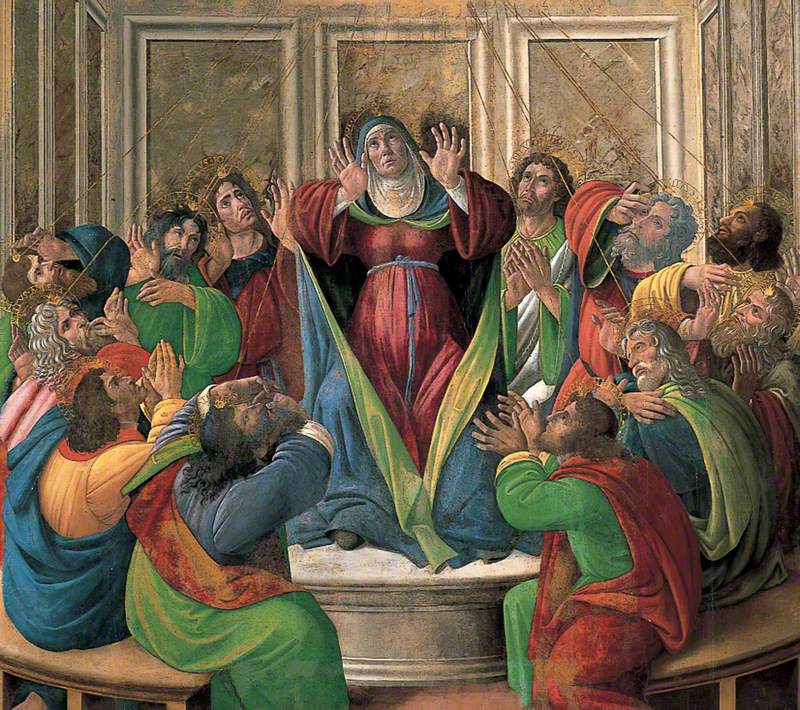

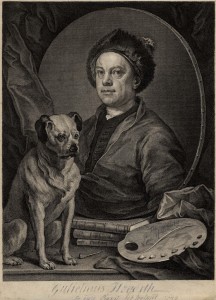

A wealthy man’s bedroom with sumptuous silk hangings and ornate woods painted in warm jewel colours is presented to us. A shaft of bright white light entering the room from the left illuminates the subject of the painting: Francis Matthew Schutz, third cousin of Frederick, Prince of Wales, sitting in a somewhat strange position and intently reading a paper.

Or is he? Extensive analysis undertaken when the painting was acquired by Norwich Castle in 1990 revealed two sets of retouches, one dating from the first half of the nineteenth century and the other from the early twentieth century, with significant overpainting of the central area carried out around the mid-nineteenth century.

Once the painting was cleaned and the overpainting removed, an astonishing detail was revealed, which transformed the whole meaning of the painting: Schutz was in fact depicted in the less dignified act of vomiting into a chamber pot, aching head resting on his hand. Moreover, a nineteenth-century label on the reverse of the painting tells us that this is no ordinary sickbed portrait: Schutz’s wife Susan, exasperated with her husband’s addiction ‘to the vice of intemperance’ and ‘under the hope of reforming him’, had commissioned Hogarth to paint him while suffering the after-effects of his debauchery. Of course, the notorious author of A Rake’s Progress, A Harlot’s Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode would be the perfect candidate for such an entertaining moral tale.

A lyre hangs on the wall below the inscription vixi puellis nuper idoneus, &c. From Horace’s Odes, it is part of a verse that has been translated as ‘For ladies’ love I late was fit, / And good success my warfare blest, / But now my arms, my lyre I quit, / And hang them up to rust or rest.’ The implication here is that Schutz, now a married man, should be giving up wine and women; however, Ronald Paulson, in his book Hogarth, suggests that it could be a hint that Schutz’s drinking ‘incapacitates him from fulfilling his marital duties.’ (Vol.3, 1993, p.269). Another inscription, added after Hogarth’s death, reads cuius octavum trepidavit aetas claudere lustrum and supposedly hints that Schutz, at the close of the fourth decade of his life, had finally given up womanising.

So why the overpainting? The ever-helpful label on the reverse informs us that Schutz’s descendants considered the painting ‘so disrespectful to his memory’ that they had the offending vomit and chamber pot painted out of existence, at least for a century or two. Trust inquisitive museum professionals to reveal them again!

Dr Giorgia Bottinelli, Curator of Historic Art, Norfolk Museums Service