Ten years ago, in 2009, the BBC arts editor and presenter Will Gompertz was on the Edinburgh Fringe with his sell-out show 'Double Art History'. He returns this August for one week – promising audiences a rapid-fire education in the 27 'isms' of modern art, with an impromptu art history exam at the end of it.

Will Gompertz's 'Double Art History – The Sequel'

Gompertz was Director of Tate Media the last time he performed. His new BBC job, which would make him the country's most visible arts reporter, was announced at the end of it.

He is back with an update, and a new 'ism' or two of his own. Ten years is a good time to revisit the themes, he said, and 'see what has happened in the intervening decade.'

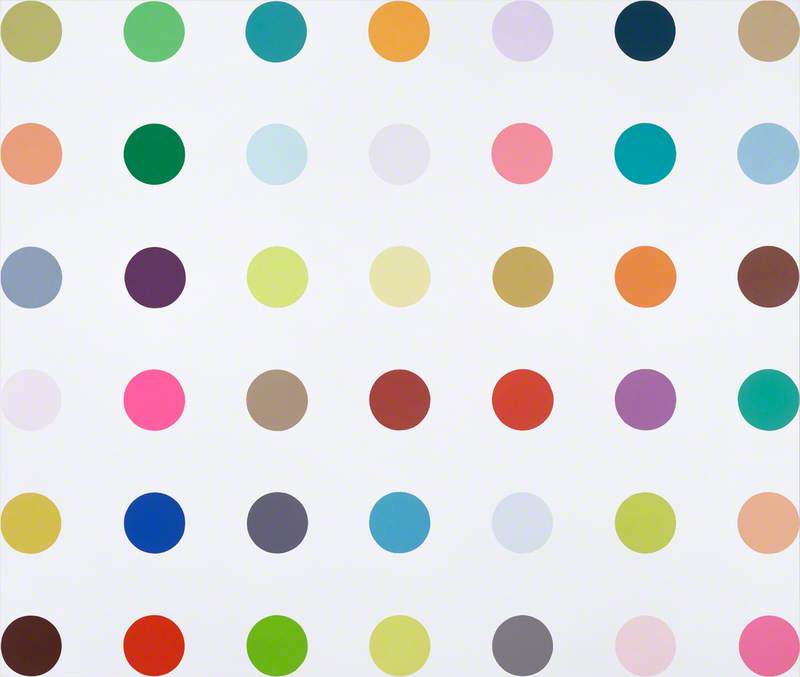

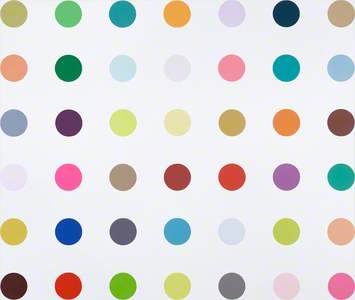

In his 2012 book What Are You Looking At? Gompertz added entrepreneurialism to the art 'isms' of the past to describe the unabashedly commercial outlook of artists like Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons.

Now the Edinburgh show is offering the latest update. I caught up with him on the eve of the festival:

'We are looking at the emergence of a new 'ism' which is social activism,' he said. 'There is no doubt, whether it is Jeremy Deller or Mark Bradford in the United States, El Anatsui in Ghana, Ai Wei Wei – all of these artists are connected with social activism and making political points within their work. Definitely something that has happened, is that art has taken a distinctly political turn, having been all about the market, all about money in the early 2000s. At the cutting edge, it is much more about activism.'

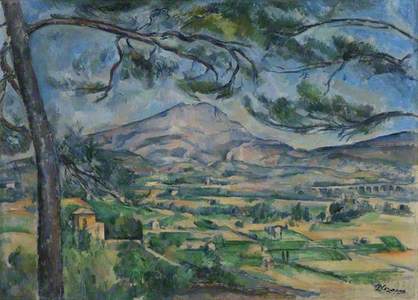

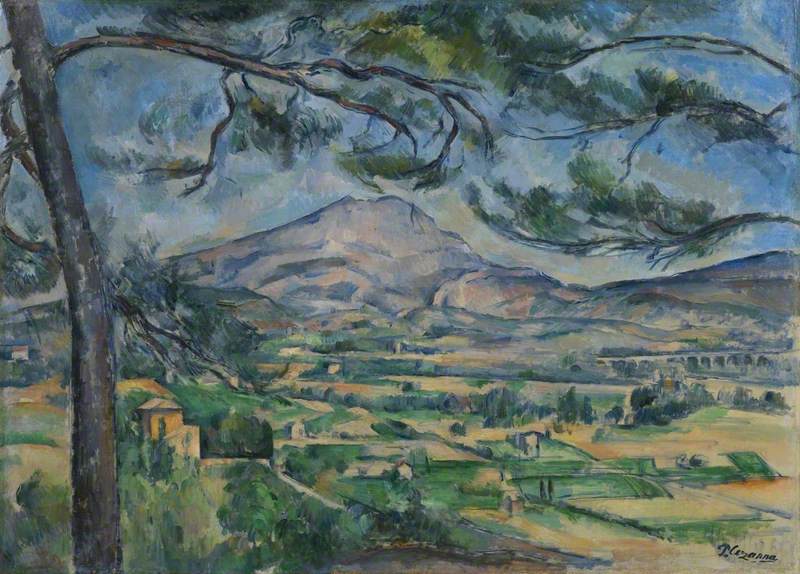

Gompertz's show features about 60–70 images, with many icons of British public collections. They include Paul Cézanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, at The Courtauld Gallery, which he has named in the past as his favourite painting of any.

The Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine

c.1887

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

He cited the 24 melting ice blocks installed at the Tate Modern last year by Scandinavian artist Olafur Eliasson, or the work of Cuban artist and activist Tania Bruguera in the Turbine Hall (who was arrested and briefly jailed several times in Havana) as a measure of the change in contemporary artists' approach.

'There is a definite re-engagement in politics from artists which hasn't been evident particularly since the 1970s,' he said.

But Gompertz will also catch up with another seismic shift of the last decade. 'Ten years ago it was still very much a white western male perspective, and that is changing so radically at the moment, from Scotland to Milton Keynes to London. There are more shows of women artists than you have ever had before. Similarly, works by people of colour are being seen and they are going for enormous amounts of money.'

In Scotland, that new approach was seen in the groundbreaking 2016 exhibition, 'Modern Scottish Women', with signature works like the portrait of Anne Finlay by Dorothy Johnstone, in the Aberdeen Art Gallery. Elsewhere it's reflected in new interest in artists like Dora Maar, and Berthe Morisot.

Maar currently only appears on Art UK as the subject of in two portraits, rather than as poet, photographer and abstract painter in her own right. They include Brenda Chamberlain's accomplished and intriguing study, Dora Maar – Intérieur Provençal, at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery.

Morisot, by contrast, is in a small but neat spread of collections from the National Museum of Wales, to the national galleries of England and Scotland, in the latter with A Woman and Child in a Garden, purchased in 1964. (Intriguingly four of the five works by the nineteenth-century artist in British public collections were added in the 1960s and 1970s – the exception is the lovely Summer's Day in The National Gallery in London, a 1917 bequest.)

A broader 'big change' is facing museums, says Gompertz: 'to rethink what they are and how they present themselves in a post-colonial age of shifting identities.' He notes that the Pitt Rivers in Oxford 'is reconsidering its entire collection and how it describes it, how it thinks about it. How it talks about the countries from whence it came and even what it is going to give back.'

Venus Rising from the Sea (Venus Anadyomene)

c.1520

Titian (c.1488–1576)

The same is true across other museums: the game has changed, perceptions have shifted, there's a demand on them to remake, rethink, re-represent their artworks and exhibits. 'Not necessarily adding new works, but making the works they have feel like they belong in the twenty-first century, not being anachronisms from another age,' he said. 'For example, the male gaze and where that belongs in a museum.' He cites this year's Royal Academy exhibition on the Renaissance nude, where over half the works were male figures, 'definitely a #metoo show or a #timesup show'.

The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her Last Berth to be broken up, 1838

1839

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Gompertz's minute-by-minute art history tour ranges to Pablo Picasso's Weeping Woman, Jackson Pollock's Summertime: Number 9A, and Duchamp's Fountain (urinal) from the Tate, J. M. W. Turner's The Fighting Temeraire from The National Gallery, voted the country's favourite painting in 2005.

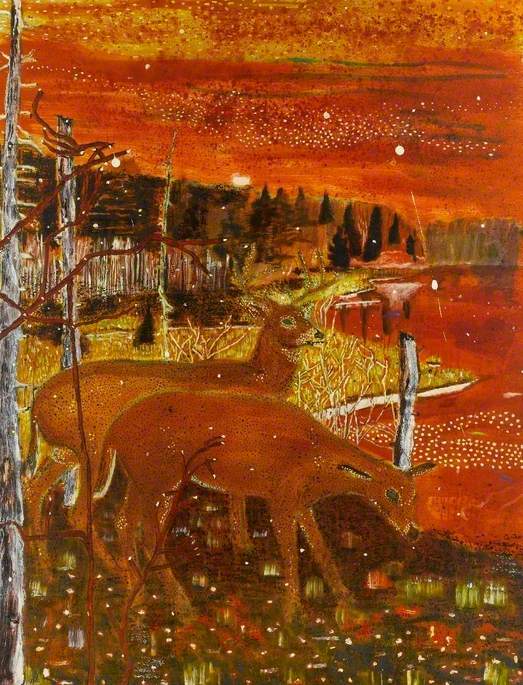

Asked for favourite Scottish artists he seemed to stumble, though he admires the Edinburgh-born Peter Doig, as painter expressing 'a sort of existential anxiety'.

His latest book, Think Like an Artist and Lead a More Creative, Productive Life, promises to offer 'a few practical clues on how usefully we might do that, beyond spending more time baking in the kitchen, at the pottery wheel or dress-making'. He writes in the introduction: 'We are all artists. We just have to believe it. That's what artists do.'

Will Gompertz's 'Double Art History – The Sequel'

Last time round at the Fringe, Gompertz won a certain fame by inviting audience members to draw a penis in different artistic styles. It produced Cubist, Pointillist and Surrealist penises, and a particularly good Pop Art one, which he kept. But he definitely isn't going to repeat that stunt, surrounded these days by that aura of BBC respectability, and perhaps mindful of that #metoo hashtag.

'I will lance the boil, so I will talk about that whole episode and why I did it. It will be addressed, but I'm not going to ask them to draw penises.' He says the show is about dodging 'highfalutin terms' that make art 'feel like distant territory'. But is it time to rein back on 'isms' altogether, terms that might be as obscure as they are over-used?

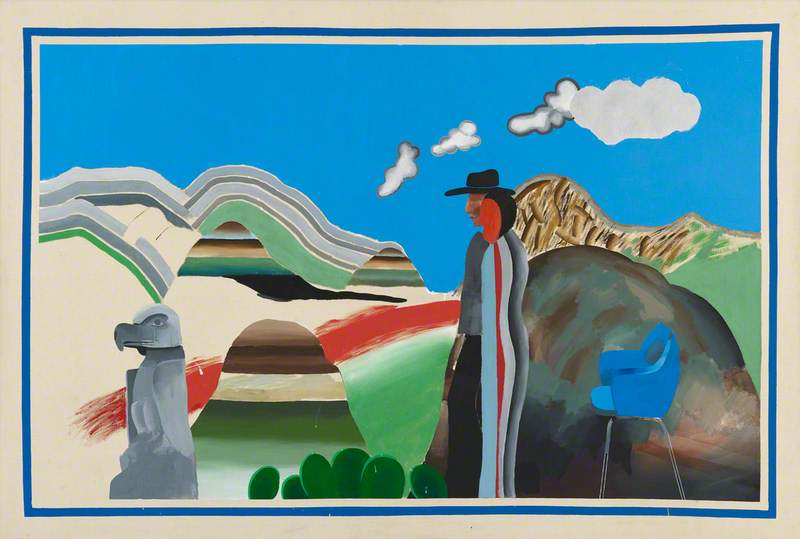

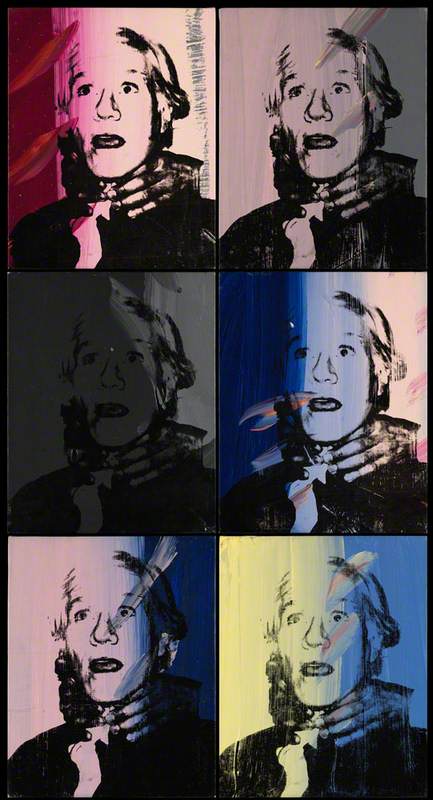

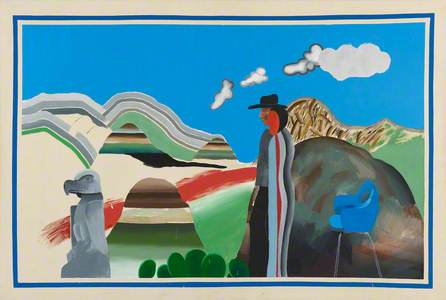

'Artists hate being put into categories. David Hockney does not like being called a Pop Artist,' he responds, but continues: 'We as a species, we need to categorise, it's a whole way of understanding our world. The Impressionists called themselves the Impressionists... the Abstract Expressionists recognised themselves as doing something very different. Andy Warhol was indubitably a Pop Artist. It's a central idea that comes along and people coalesce around the idea, produce work that reflects the time,' he says.

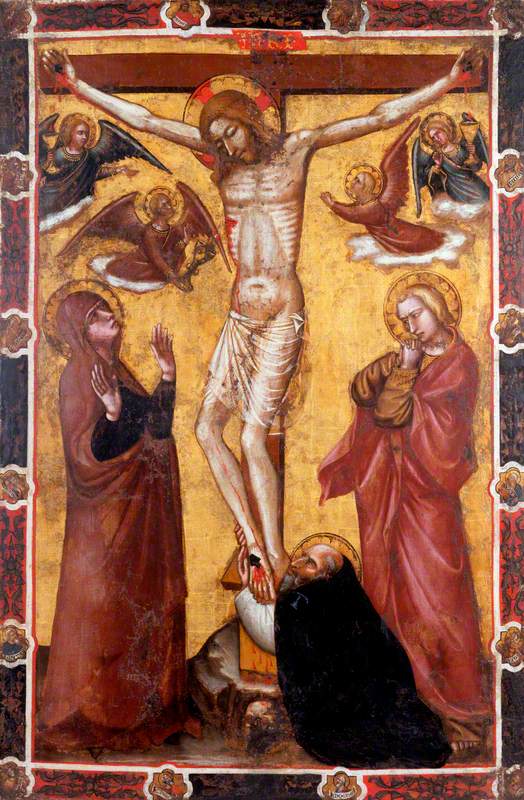

'There are certain common characteristics about certain types of art-making that enable one to put it into a group of like-minded, mutually influenced works,' whether that is late Renaissance Italian or something vastly more contemporary. 'They are fairly blunt tools but I think they are effective and useful tools. Some artists subscribe to them. The Surrealists were a group of artists, they became a movement. The Constructivists saw themselves as a movement to produce a visual language to support the new Communist vision, the Bolshevik state.'

Will Gompertz's 'Double Art History – The Sequel'

So if you're at the Fringe this year don't miss your chance to brush up on your 'isms' with one of the BBC's finest – he promises there will be no penis drawing.

Tim Cornwell, freelance arts writer

'Will Gompertz: Double Art History – The Sequel' is at the Underbelly venue in Bristo Square, Edinburgh from 19th to 25th August 2019. You can book tickets here