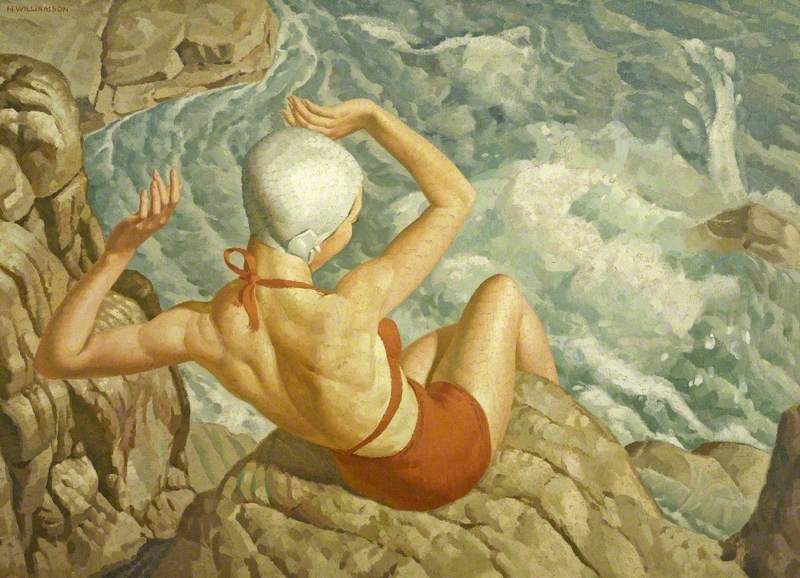

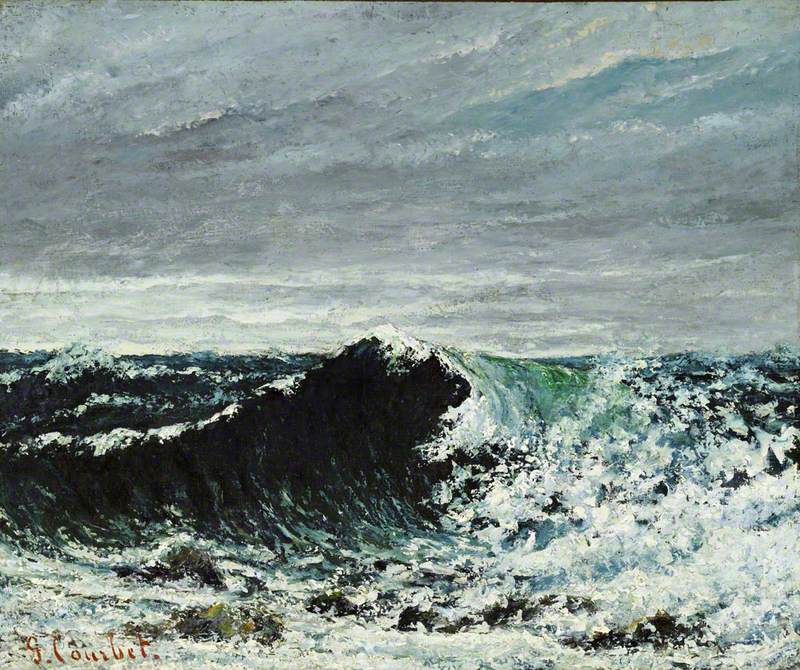

The Oxford English Dictionary defines water, when pure, as transparent, colourless, tasteless and inodorous – hardly the most inspiring of descriptions. Yet water holds a magnetic appeal for human beings. Aside from being essential to life, its fascinations are universal and all of us yearn to immerse ourselves in its magical, liquid embrace.

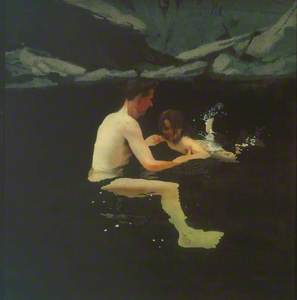

Boy Bathing

(study for 'Summer Morning') c.1886

Henry Scott Tuke (1858–1929)

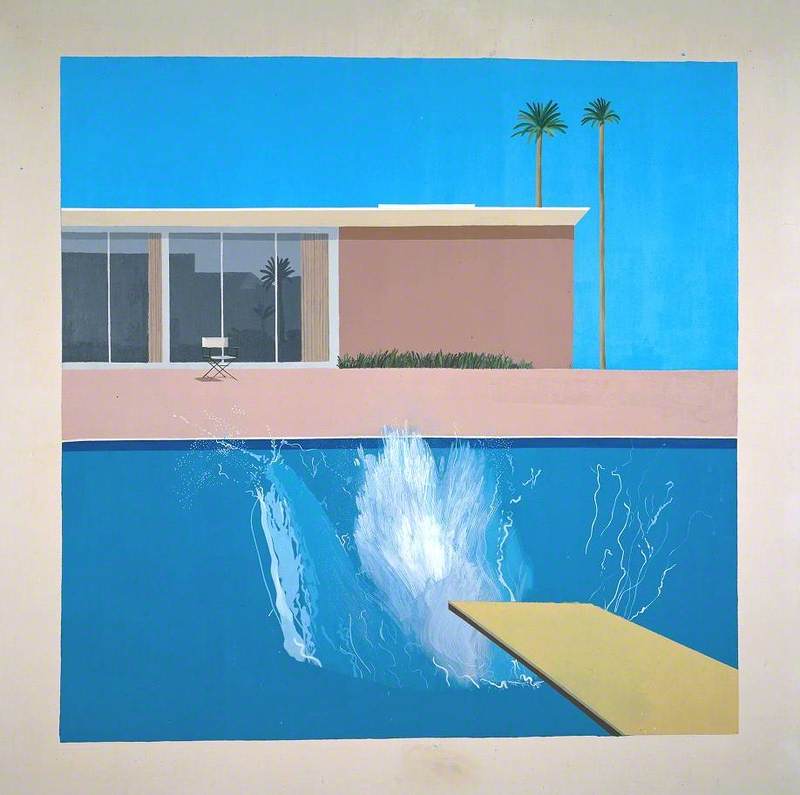

Writer Roger Deakin argued that when you give in to that yearning you feel your body as mostly water and it begins to move with the water around it. 'To swim is to experience how it was before you were born,' he said. 'Once in the water, you are immersed in an intensely private world as you were in the womb. These amniotic waters are both utterly safe and yet terrifying, for at birth anything could go wrong, and you are assailed by all kinds of unknown forces over which you have no control… A swallow-dive off the high board into the void is an image that brings together all the contradictions of birth. The swimmer experiences the terror and the bliss of being born.'

The Tomb of the Diver (detail from the underside of the top slab of the grave)

c.470 BC, fresco on plaster by unknown artist

Our corporeal relationship with water, innate and authentic, has prompted a long line of literary masterpieces: Charles Sprawson's Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer as Hero, Leanne Shapton's Swimming Studies, William Finnegan's Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, Tim Ecott's Neutral Buoyancy: Adventures in a Liquid World. Swimming, surfing and diving are the subjects of a stream of compelling books on the life aquatic – none more so than Roger Deakin's Waterlog: A Swimmer's Journey Through Britain.

First published in 1999, Waterlog became an instant bestseller and is now an established classic of the nature-writing canon. Its author lived in a farmhouse in Suffolk for the best part of four decades and regularly started each day with a mind-cleansing swim in its frog-rich moat. Persuaded that 'following water, flowing with it, would be a way of getting under the skin of things, of learning something new,' Deakin set out from his moat on a journey to swim the British Isles, creating in the process an enchanting portrait of water in the wild.

Some commentators have credited Waterlog with kick-starting our current obsession with wild swimming. Sport England reports that more than four million people are now swimming outdoors, motivated in part by its physical and mental benefits (cold water immersion decreases blood pressure and cholesterol, stimulates the immune system and contributes to a general sense of well being). This backs up anecdotal evidence that points to a rise in the popularity of outdoor swimming, which includes booming membership figures for outdoor swimming clubs and more venues opening throughout the year to cater to the demands of increasing numbers of winter swimmers.

Writer and journalist Rebecca Mead maintains, quite rightly, that the sport's attractions can be hard to imagine if your vision of outdoor swimming is synonymous with summer holidays abroad. '[It's] estimated that nobody in the UK is ever more than seventy miles from a stretch of coastline,' she says. 'But British waters are incontrovertibly cold. Sea temperatures rarely creep above 20 degrees Celsius and England's freshwater bodies, which are often fed by underground springs, tend to be even chillier… The hardiest wild swimmers keep going even when water temperatures fall below freezing; they pack, along with a microfibre towel and a thermos of tea, an axe, for breaking a channel through the ice.'

Going by the number of waterbiographies that have appeared over the last several years, women would seem to make up the greatest number of regular cold-water swimmers. Cultural historian Lara Feigel identifies waterbiographies as confessional titles in which 'the author, often a woman, tries to work out something in her life through swimming in beautiful, often inhospitable waters.' In her Guardian review of Ruth Fitzmaurice's I Found My Tribe, Feigel references Amy Liptrot's The Outrun, Olivia Laing's To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface, Victoria Whitworth's Swimming with Seals and Jessica J. Lee's Turning: A Swimming Memoir.

'Does [wild swimming] offer particular appeal to women?' she says. 'There's the joy of suddenly feeling your body weightless, immersed in a new element … Where the expanse of water is large, there's the freedom of endlessness. And there are hormonal benefits. Jessica J. Lee writes about her need for the endorphins released by cold water. Apparently, she's met opiate users who claim that heroin replicates the effects of cold water swimming. [And] for Fitzmaurice there's also, crucially, the communality of swimming with friends.'

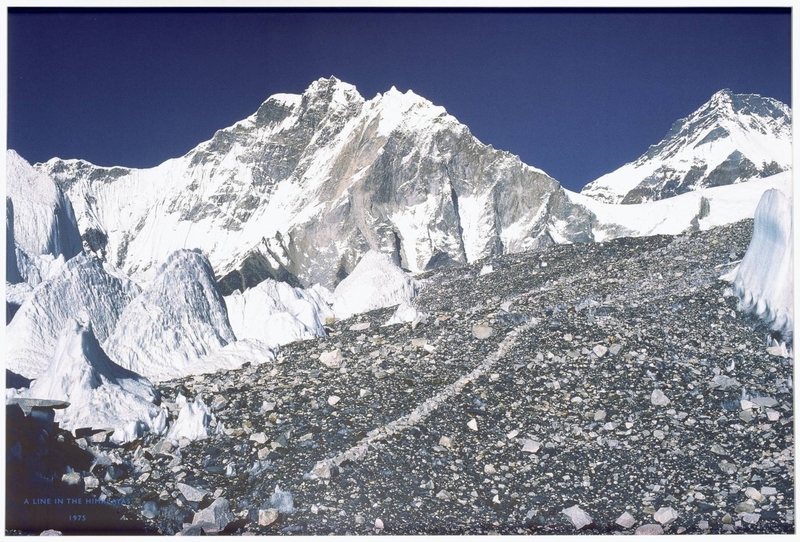

What all of these waterbiographies underscore is that swimming outdoors constitutes an act of defiance. Roger Deakin observed that most of us live in a world where more and more places and things are signposted, labelled and interpreted. 'There is something about all this that is turning the reality of things into virtual reality,' he said. 'It is the reason why walking, cycling and swimming will always be subversive activities. They allow us to regain a sense of what is old and wild in these islands, by getting off the beaten track and breaking free of the official version of things.'

The pursuit of endorphins cited by Jessica J. Lee is what drives swimmers to brave the coldest of waters. Endorphins make us feel good while simultaneously anaesthetising us from the discomfort of exposure to low temperatures, but some swimmers elect to help things along by donning a wet suit, which makes bearable long periods of immersion. And wet suits are essential for anyone wishing to surf or dive in chilly seas.

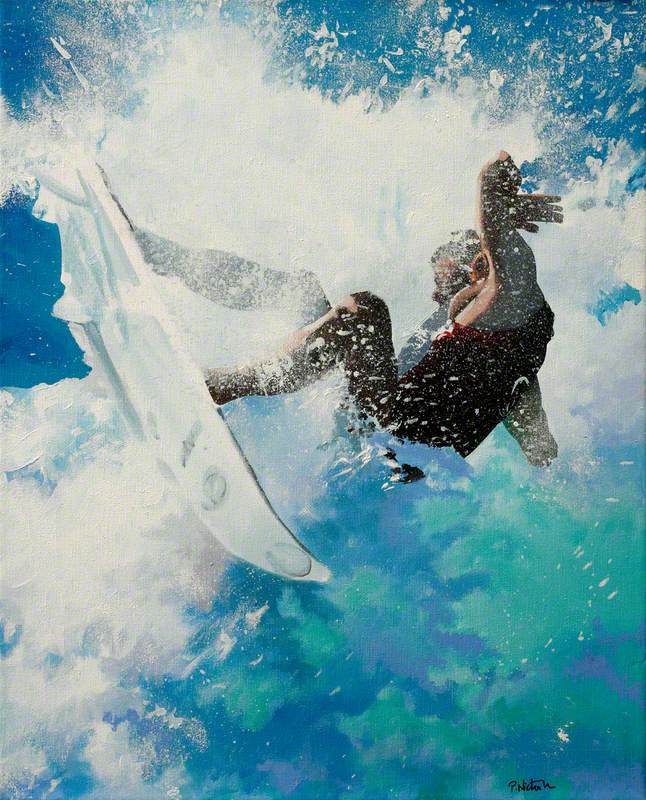

Nobody has written about the thrills and horrors of surfing more brilliantly than William Finnegan. In Barbarian Days, a memoir about Finnegan's lifelong obsession with the sport, the waves are the stars and the author is under no illusion that the allure of the biggest waves is intimately connected to their lethal nature: 'Being out in big surf is dreamlike. Terror and ecstasy ebb and flow around the edges of things, each threatening to overwhelm the dreamer. An unearthly beauty saturates an enormous arena of moving water, latent violence, too-real explosions, and sky. Scenes feel mythic even as they unfold. I always feel a ferocious ambivalence: I want to be nowhere else; I want to be anywhere else.'

The great Australian writer Tim Winton has written numerous novels in which surfing plays a major role. Interviewed around the time that Breath was published in 2008, Winton made a perceptive and lyrical connection between surfing and writing. 'Most of the time [with surfing] you're waiting,' he said. 'And it's quite pleasant, sitting in the water waiting. But you are expecting that the result of a storm over the horizon, in another time zone, usually days old, will radiate out in the form of waves. And eventually, when they show up, you turn around and ride that energy to the shore. It's a lovely thing, feeling that momentum. If you're lucky, it's also about grace. As a writer, you roll up to the desk every day, and then you sit there, waiting, in the hope that something will come over the horizon. And then you turn around and ride it, in the form of a story.'

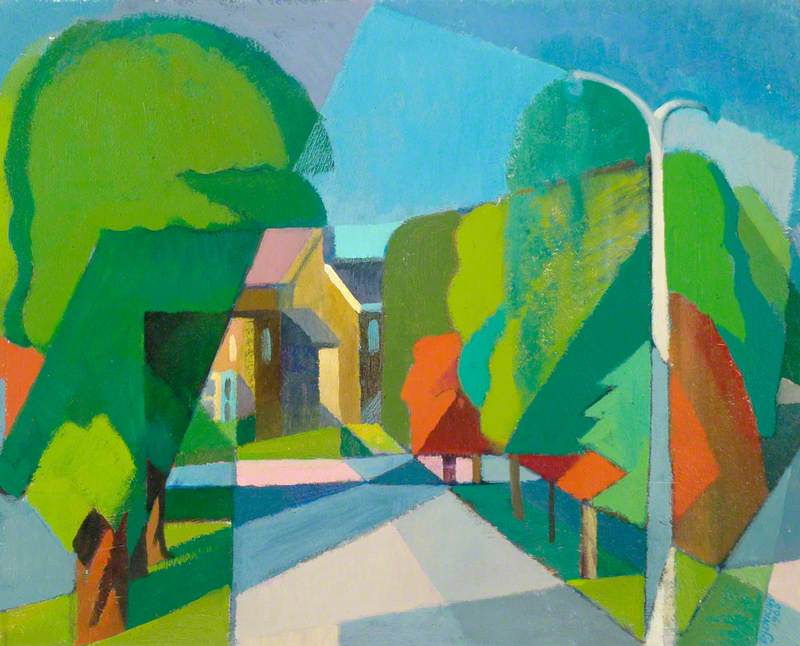

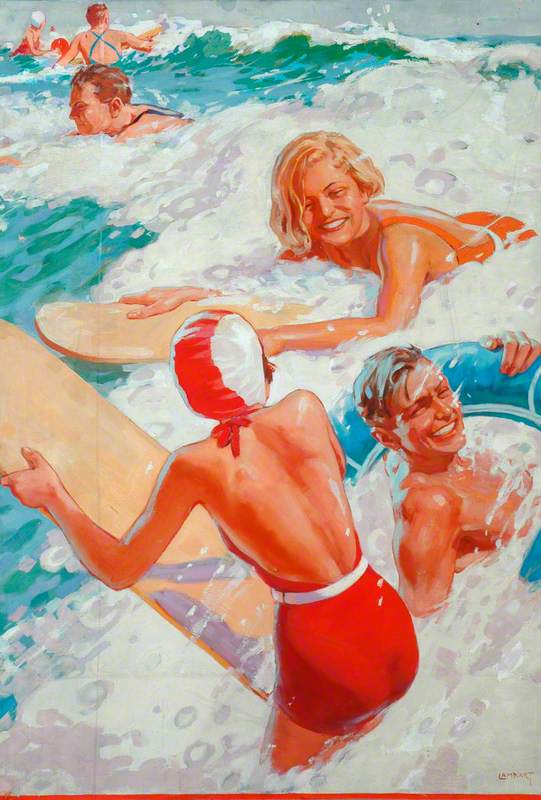

Newquay

(Great Western Railway poster artwork) 1937

Alfred Lambart (1902–1970)

While surfing tends to be a highly visible activity, swimming is a quieter, more reflective pursuit and the same is true of diving. Tim Ecott alludes to this in the opening pages of Neutral Buoyancy: 'In Italy, a young woman once told me that learning to dive had mended her broken heart… In Switzerland, a man told me that he preferred to dive in alpine lakes rather than tropical seas. He said he found the marine life in warm waters too distracting; there was too much colour, too many things to take in. For him the joy of diving was the opportunity to see inside himself. In order to examine his own character he needed to be in cold, dark, deep water where diving, just breathing underwater was an end in itself.'

Diving can be uplifting, transcendent even, but it can also be disappointing. For every once-in-a-lifetime descent, when you find yourself playing with seals in the waters off Cape Town or gliding over the sunken city of Baiae in the Gulf of Naples, there are those routine, low visibility dives, which yield little of note for the logbook. On those occasions, the only rewards are the sensation of hovering weightless in a body of water and watching your air bubble eagerly to the surface.

Paul Bonaventura, independent producer and curator