In 2017, the team at Google's DeepMind used AI to defeat world champion Lee Sedol in the complex Chinese game of Go. Shortly after the event, Lee Sedol retired from the game, saying 'AI is an entity that cannot be defeated.' But even in 2024, it seems AI is still struggling with something very human: drawing hands.

— no context memes (@weirddalle) January 22, 2023

Hands with six or more fingers, two thumbs, or seemingly no joints are one of the key giveaways that an image has been created by generative AI. The problem, as Kyle Chayka writes in The New Yorker, is that hands can 'look very different from different angles.' To train AI, you need clear and vast datasets. One of the problems is that hands are often less visible in images than faces and also much smaller. Generative AI works by using algorithms of probability to generate its outputs; it is not learning from biology. Peter Bentley, a professor of computer science at UCL, reminds us that AI has 'no understanding of what a hand really is.' And as Mira Murati, the Chief technology officer of OpenAI, said recently to Bloomberg: we are a long way off Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), which would be able to understand what a hand really is.

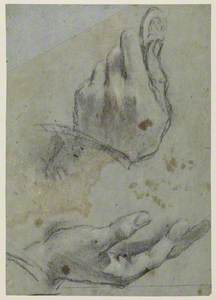

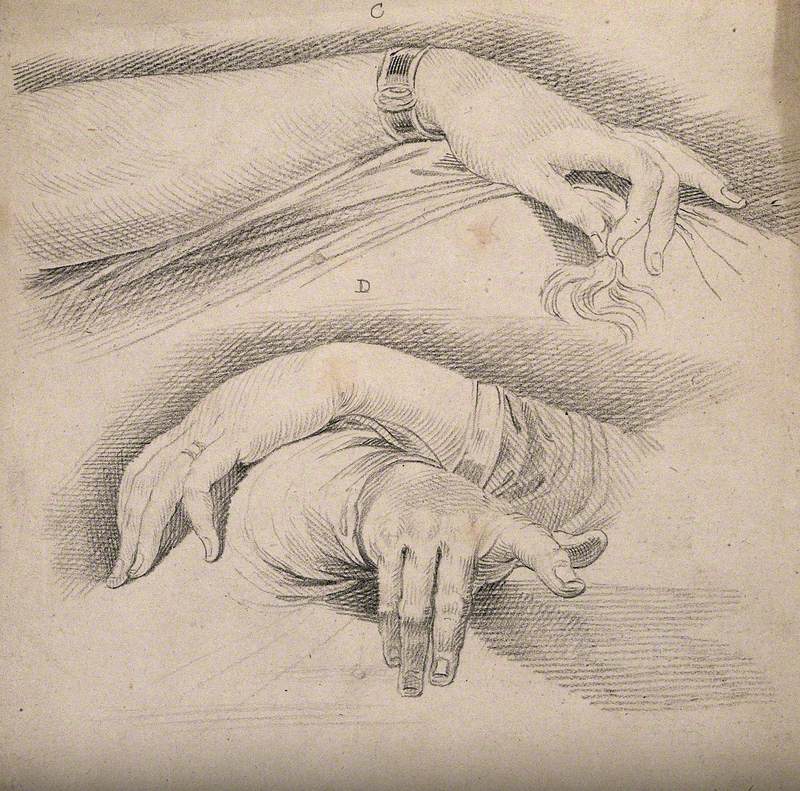

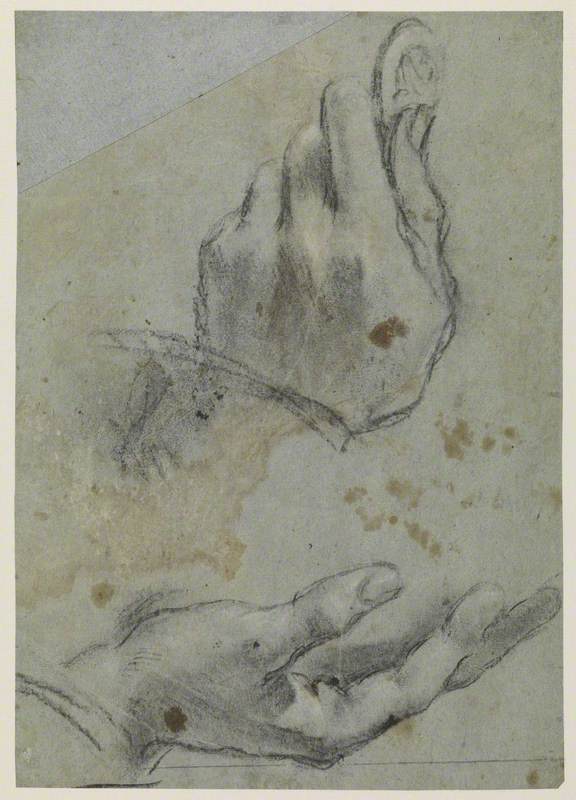

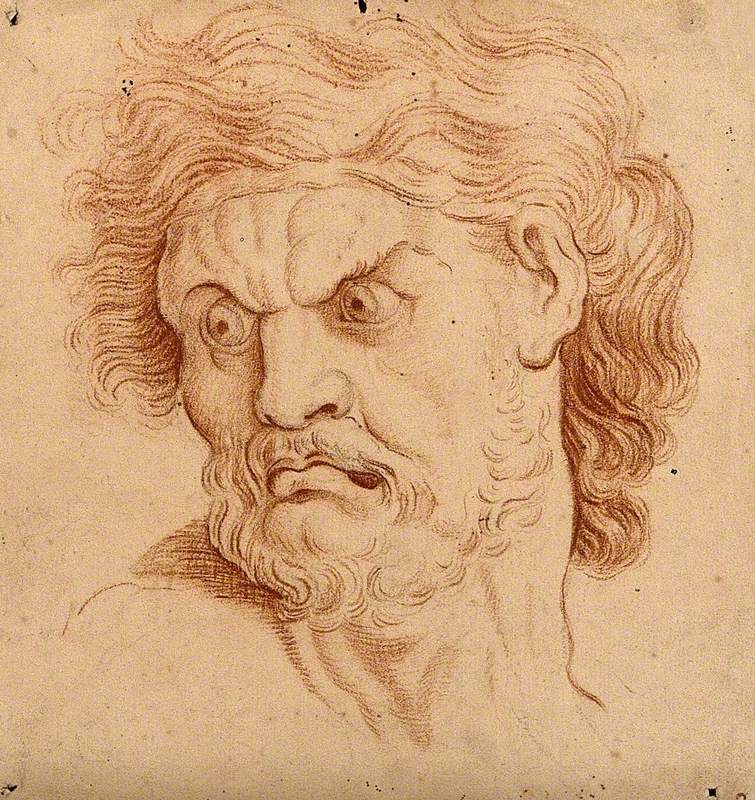

For human artists, hands are both tool and subject, though they are also famously difficult to draw accurately. Artists, however, can learn from biology, unlike AI. Jacopo Bassano the elder's Studies of Hands is an example of the way artists studied hands, often over and over, to get them right. In the Renaissance, artists began studying human anatomy to increase their understanding of the intricacies of the body and draw it more accurately.

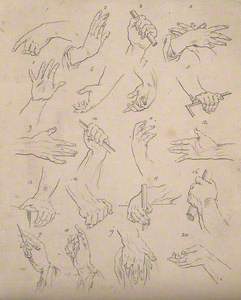

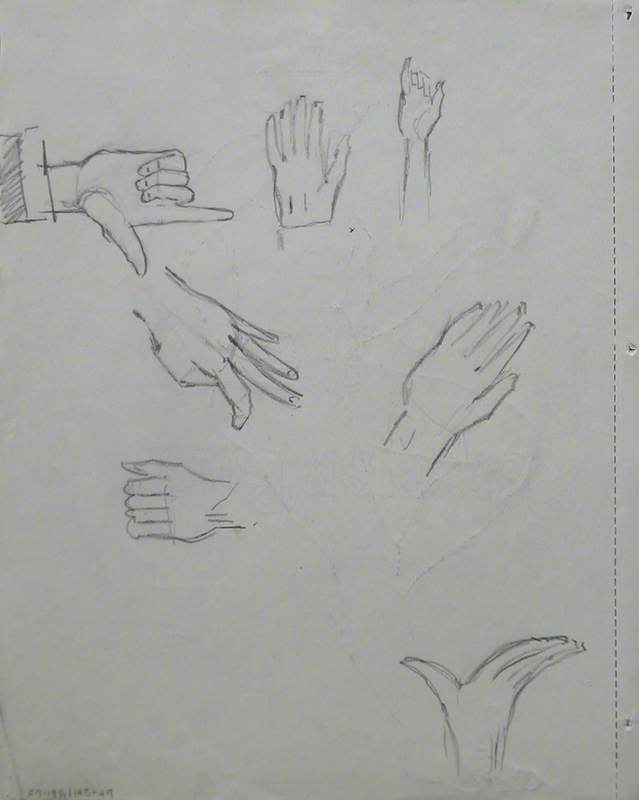

Because hands are so difficult to draw, artists often practice multiple different hand positions. I particularly like the hand on the right-hand side in the middle of A Study of Hands by John Flaxman – the little finger elevated almost as though positioned to become a hand shadow puppet.

Flaxman worked in the nineteenth century. He was able to create beautiful realistic drawings of hands by studying the anatomy of hands and arms like his predecessors in the Renaissance, learning about the inner workings of the body to accurately depict its exterior.

Another artist who studied and drew human anatomy was L. S. Lowry. In one case, he practised many unique hand positions on the back of another work: the one with the cuff of a jacket visible is very much in a recognisable Lowry style. The artist's project is two-fold: both to render accuracy and to communicate their own artistic language. AI does not seem to be aiming for this – it is a photorealist. The hand in the lower right corner of the image is fanned out so far, it almost resembles something entirely different. It has artistic expression – it is distinctively a Lowry.

Artists can also learn from body language, picking up on the nuances of expression and placement of hands, in a way that AI cannot. Two plates from a fascinating book owned by the Wellcome Collection, called Essays on Physiognomy, provide an insight into what AI is missing. Physiognomy is a pseudoscience that claims to be able to assess a person's character from their appearance. It is now rarely practised and hopefully not adopted by AI, although there does seem to be concern that this could be occurring.

Female and Male Hands, Above and Below, Respectively

c.1793

Thomas Holloway (1748–1827) (associated with)

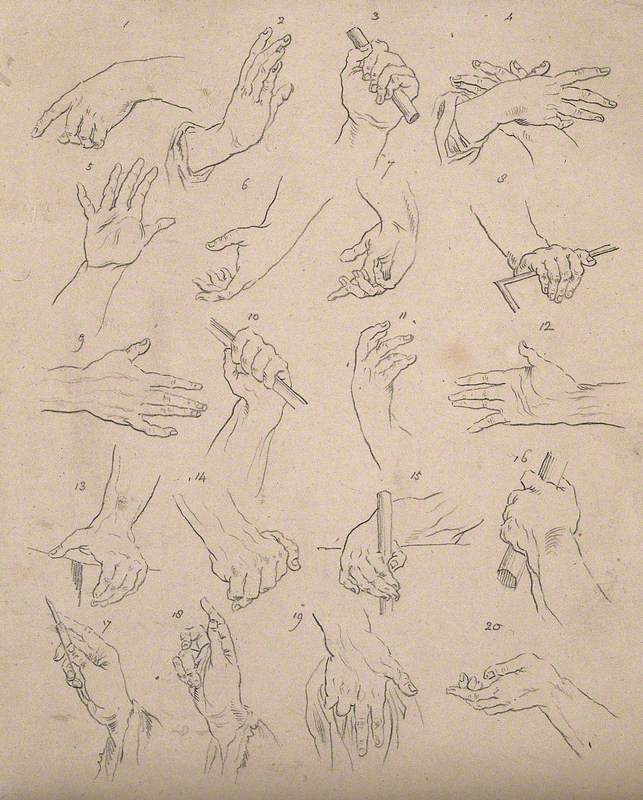

In these drawings of hands, you can see the personality the artist is trying to weave into them to accurately depict hand movements. Whilst twenty hands seems a lot, it is only scratching the surface of the nearly infinite ways a hand can move. The human hand is made up of 27 bones, 27 joints, 34 muscles and over 100 ligaments and tendons.

Twenty Hands Shown in Various Postures, Movements and Deeds

c.1793

Thomas Holloway (1748–1827) (associated with)

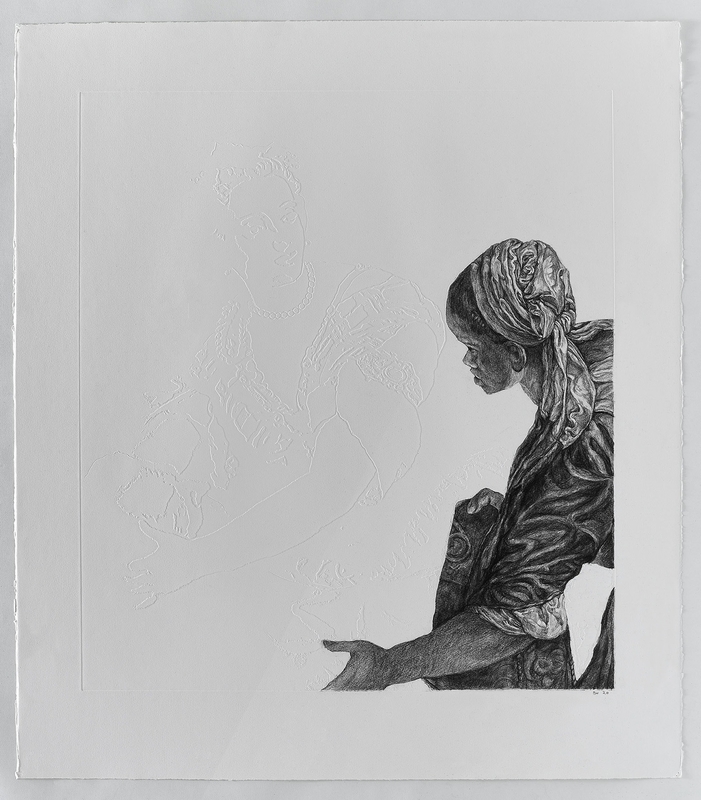

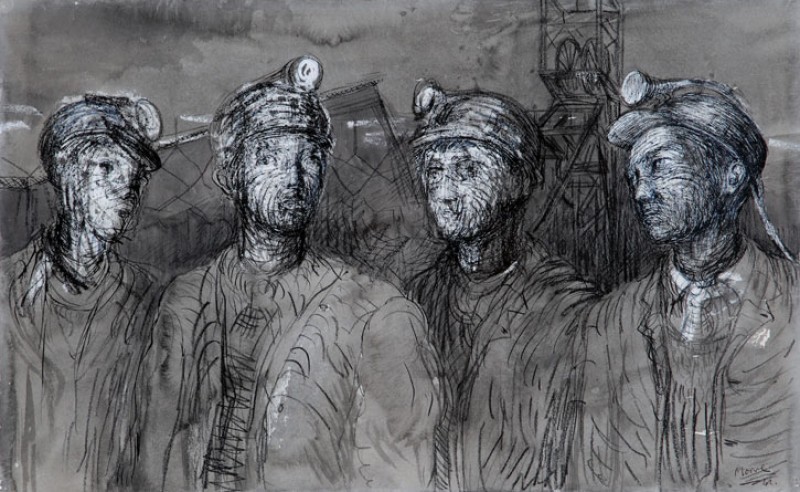

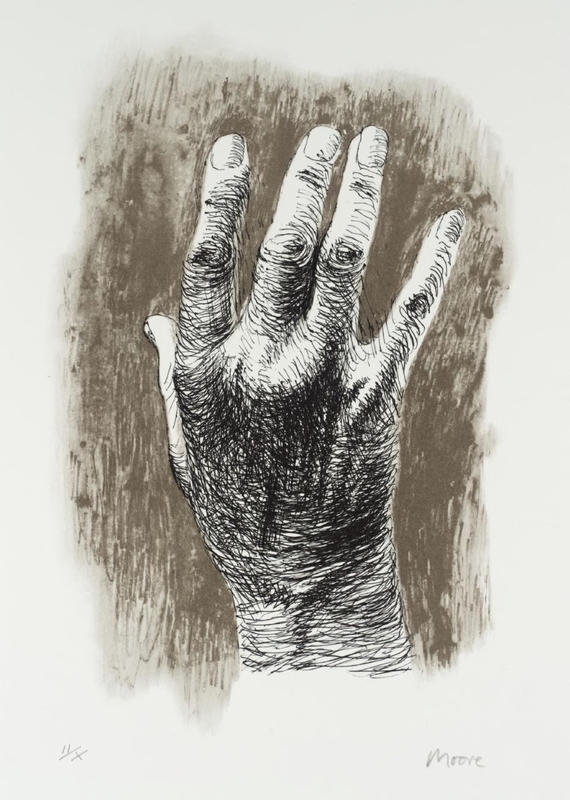

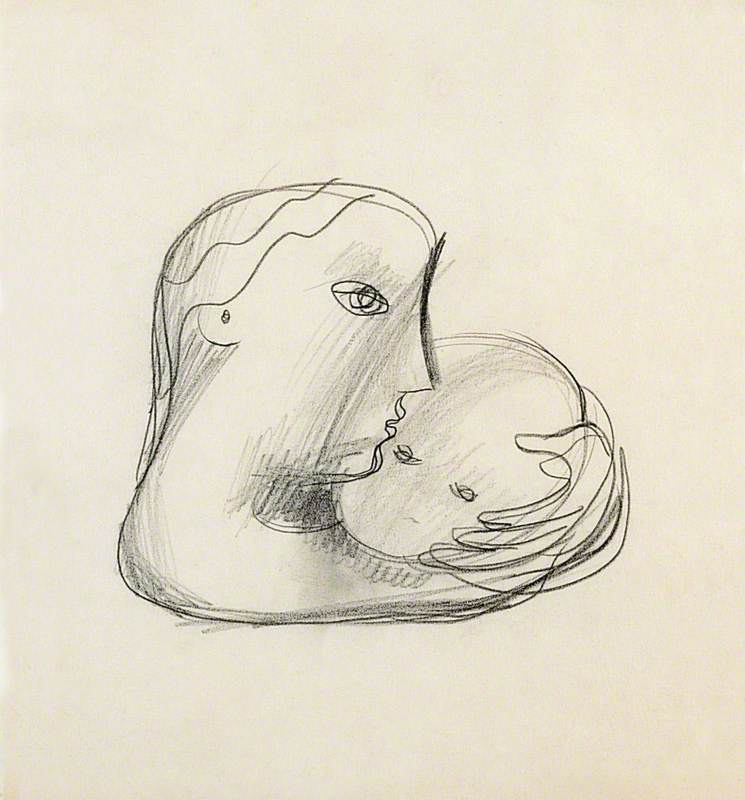

Many artists have used drawing to practice before creating in another medium, and sketches of hands are a prime example of this. One artist in particular who was prolific in his drawings was Henry Moore. Godfrey Worsdale, Director of the Henry Moore Foundation, wrote in Henry Moore Drawings: The Art of Seeing, that Moore wanted to 'understand drawing as a science and as an art.' Moore saw drawing as a 'necessary life skill' and I think, for us, being able to understand AI and be aware of its capabilities, good and bad, will end up being a necessary life skill for generations to come.

Moore produced over 7,500 drawings in his lifetime. Towards the end of his life, Moore's health worsened and drawing was one of the only things he was able to do, including drawing his own hands. To choose to draw something as difficult and complex as hands when his health was worsening shows the gravitas Moore had as an artist.

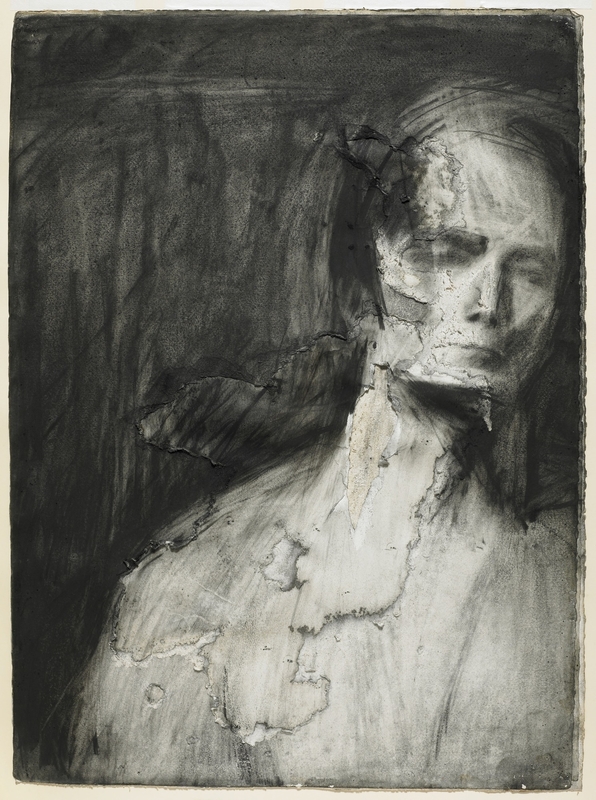

Crucially, drawing by humans is not just about seeing, it is about reflecting, contemplating, and releasing a creative energy. It is about feeling, empathy and so much more. Hands in Moore's earlier drawings are harder to see. But he does not shy away from them completely. Knowing these will often be made into sculptures, the detail may have been reduced on purpose.

In Marcus du Sautoy's The Creativity Code: How AI is Learning to Write, Paint and Think he asks: 'Could our creativity be more algorithmic and rule-based than we might want to acknowledge?' If AI begins to draw hands beautifully with creative intent, does that mean the artist is obsolete? As many have said, art is what makes us human. Art is unique to us as a species, as far as we know. When AI begins to take a part in it, the question is raised: what does it mean to be human? This is complicated, of course, by the fact that AI is created by humans. Art UK itself has used AI to help identify duplicate records and for tagging purposes.

AI image-makers have been notoriously bad at rendering hands. Now, they’re getting better and could make deep fakes harder to spot. https://t.co/fgsKPewW6q

— The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) March 26, 2023

In March of this year, Midjourney, a generative AI company, proclaimed they had been able to solve the problem of creating realistic images of hands using AI. However, this was met with fear rather than celebration as this meant that fake images could be more difficult to identify, potentially causing deepfakes and fake news to proliferate.

Artist Amelia Winger-Bearskin said: 'For AI to become a useful tool for humanity, it has to understand what it is to be human, and the anatomical reality of being human.' Perhaps we are on the road to a world in which AI understands what it is to be human, but that should also include an understanding of the very human challenges of drawing hands.

Alice Read, writer and digital arts marketer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

.jpg)