You may have heard of the term 'Pre-Raphaelite' or 'Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood', but may not be sure what it means.

The history of this artistic movement is not neat and convenient, but messy and at times scandalous. This article will give you a short introduction to what it was, who the artists were, and where you can find some of their works.

Firstly, we must go back to 1848, where the story begins.

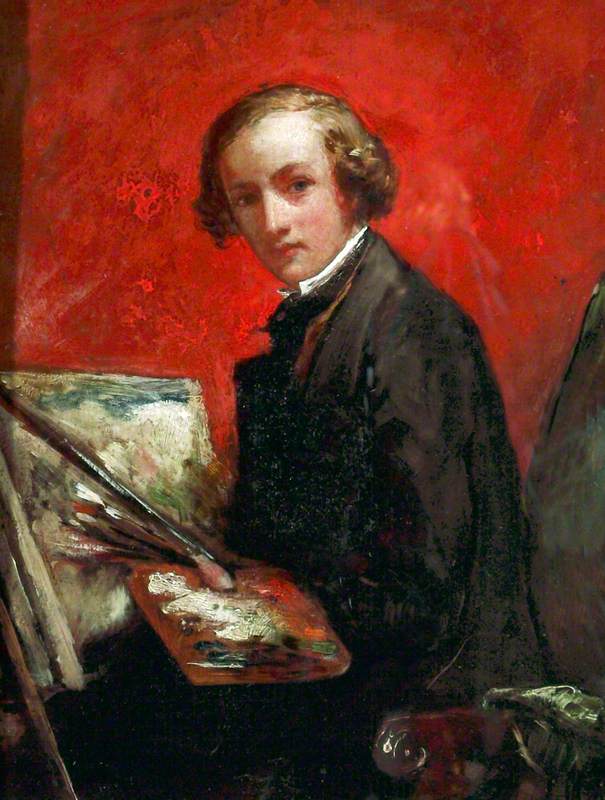

The painter William Holman Hunt was studying at the Royal Academy and displayed his work The Eve of Saint Agnes at the Academy's Summer Exhibition. It was based on the poem of the same name by the Romantic poet John Keats.

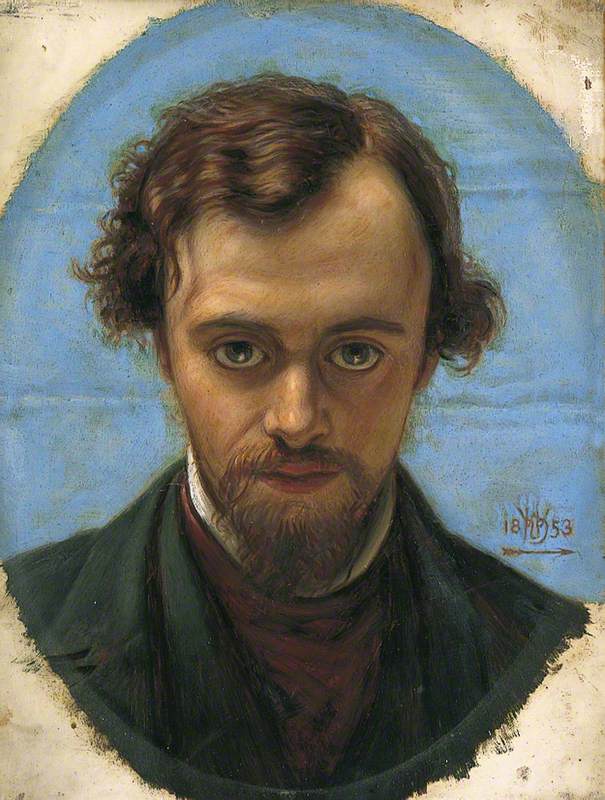

Fellow aspiring painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti saw it and declared it to be the finest of works on display. This led to Rossetti and Holman Hunt striking up a friendship and they began to share lodgings in London, financed by the sale of the painting. Another Academy student, John Everett Millais, joined Rossetti and Hunt to form what they called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and they met for the first time in Millais's parents' house, in London's Gower Street.

But what did Pre-Raphaelite mean?

The group objected to the great influence of the works of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), who had been the first President of the Royal Academy. Rather insultingly, they referred to him as 'Sir Sloshua' as they didn't like his style – they wanted to break from this tradition and paint detailed works, with bright colours, influenced by Romantic poetry, a deep sense of High Anglican Christianity and their imagining of the medieval world.

As a template for this, they looked to Italian painting of the Quattrocento (which means the fifteenth century – quattrocento literally means 'four hundred' and is how Italians refer to that time). The group thought that Mannerist painters like Michelangelo and those who followed him – but particularly Raphael – had ruined painting by bringing in Classical poses from the ancient world and elegant compositions. They wanted complex compositions, vibrant colours and for works to be saturated with detail.

So they thought they would paint in the manner of works before Raphael – hence 'Pre-Raphaelite'. They also wanted it to sound like a movement, with ideals and goals, so they dubbed themselves 'the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood'.

In 1848 Millais was just 19, Rossetti 20 and Holman Hunt 21. They were young artists who wanted to rip up the rulebook, even if it meant going backwards to go forwards...

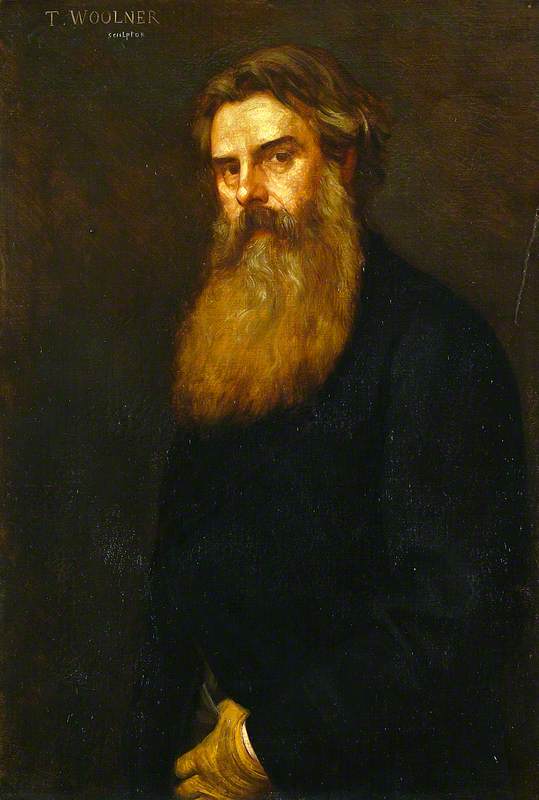

They convinced four other men to join this band – they were the painters James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens, the sculptor Thomas Woolner (who was also a poet), and Rossetti's brother William Michael Rossetti, who wasn't an artist but a critic and poet. They had also asked Rossetti's teacher Ford Madox Brown to join, but he declined, although was generally supportive of their efforts. So then there were seven...

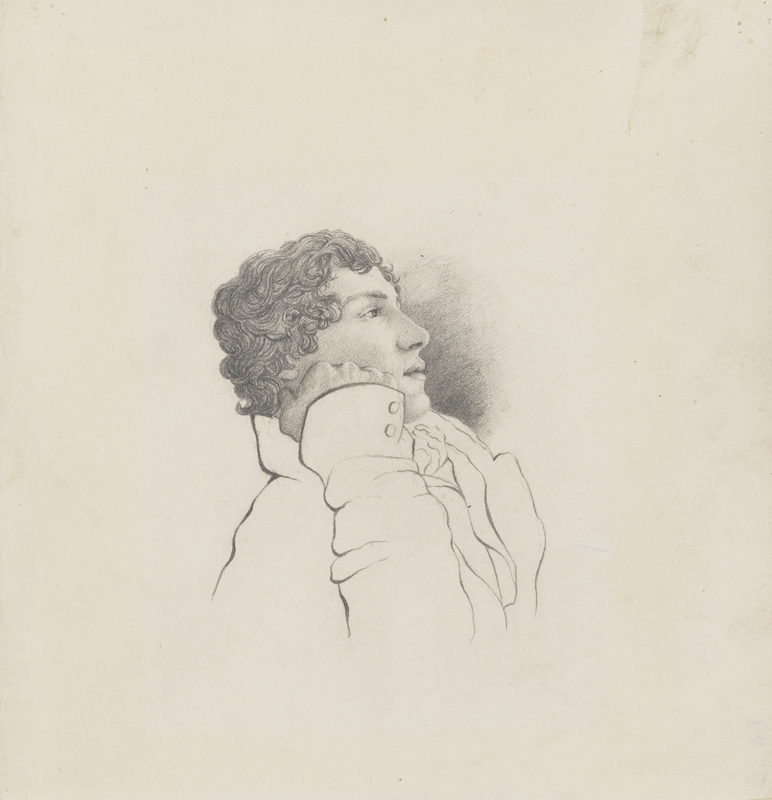

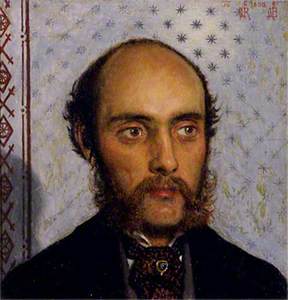

William Michael Rossetti (1829–1919), by Lamplight

1856

Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893)

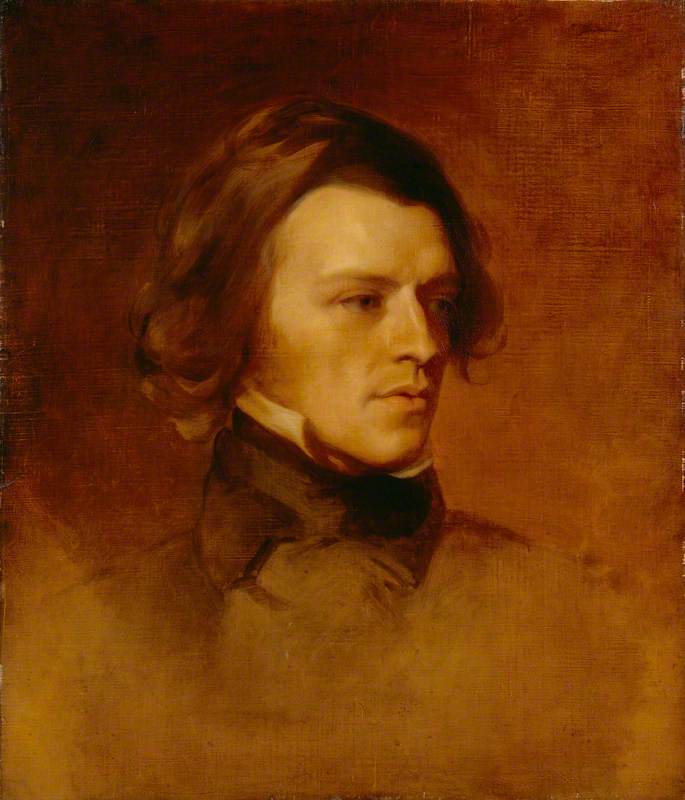

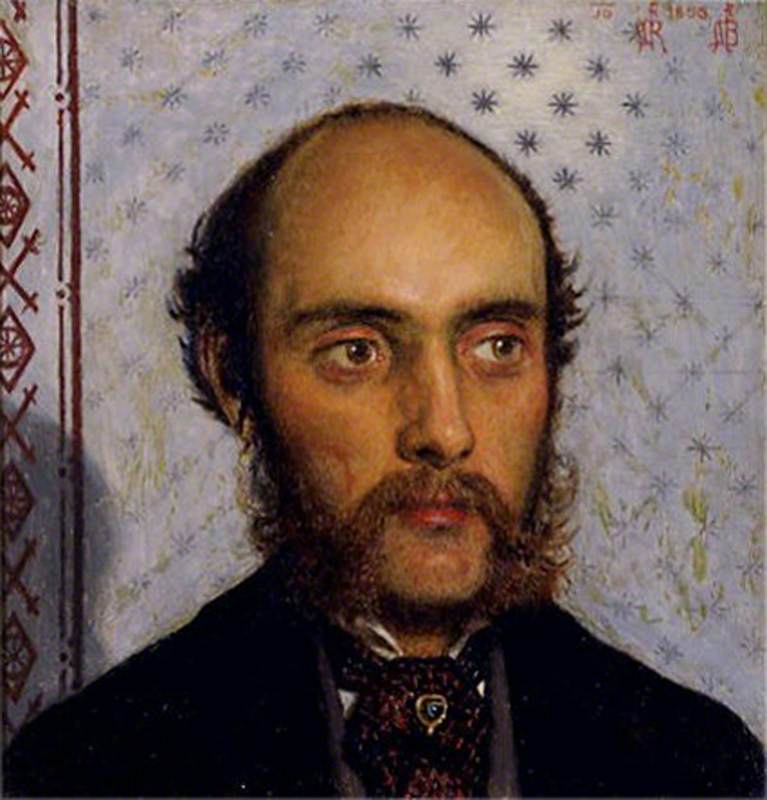

Thomas Woolner (1825–1892)

1879

Alphonse Legros (1837–1911)

Holman Hunt's The Eve of Saint Agnes predated the Brotherhood, but the first works to be created under the banner of the movement were by all three of the core trio – Holman Hunt, Millais and Rossetti. They agreed that they would sign their works with the initials 'PRB' to mark them as part of their secret society.

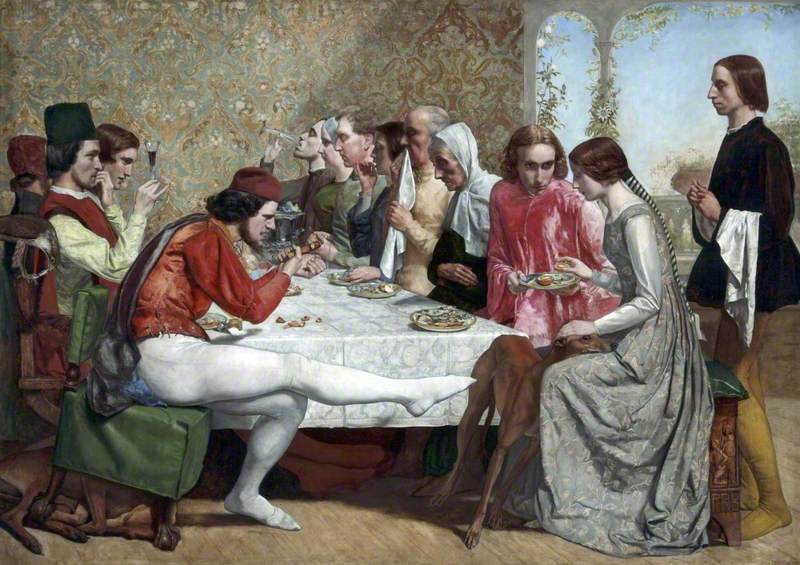

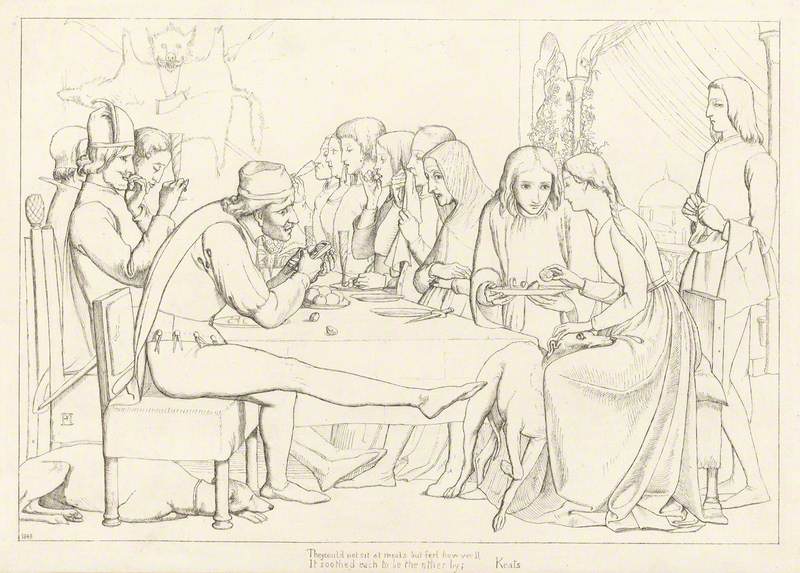

Millais exhibited the painting Isabella at the Royal Academy in 1849. It is now in Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery.

You can see from the study he made for it that the painting is – like Holman Hunt's The Eve of Saint Agnes – inspired by the poetry of John Keats. Underneath, Millais has written the lines 'They could not sit at meals but feel how well / It soothed each to be the other by;' which are lines from the poem Isabella; or the Pot of Basil.

The poem itself is based on an episode in the medieval Italian work Boccaccio's Decameron. It's a rather grisly tale – the titular Isabella is due to be married off to 'some high noble', but instead she falls in love with one of her brothers' employees – Lorenzo. As is customary in these kinds of stories, the brothers subsequently murder Lorenzo and bury his body. However, his ghost comes to tell Isabella of the crime in a dream. Naturally, she exhumes Lorenzo's body – and this is where the pot of basil comes in. She buries Lorenzo's head in the pot, and pines for him.

Millais's painting depicts the early part of the poem, where the lovers are attempting to keep their illicit affair secret. The artist is also not content with just signing 'PRB' – the wooden bench Isabella sits on has PRB carved into the leg too!

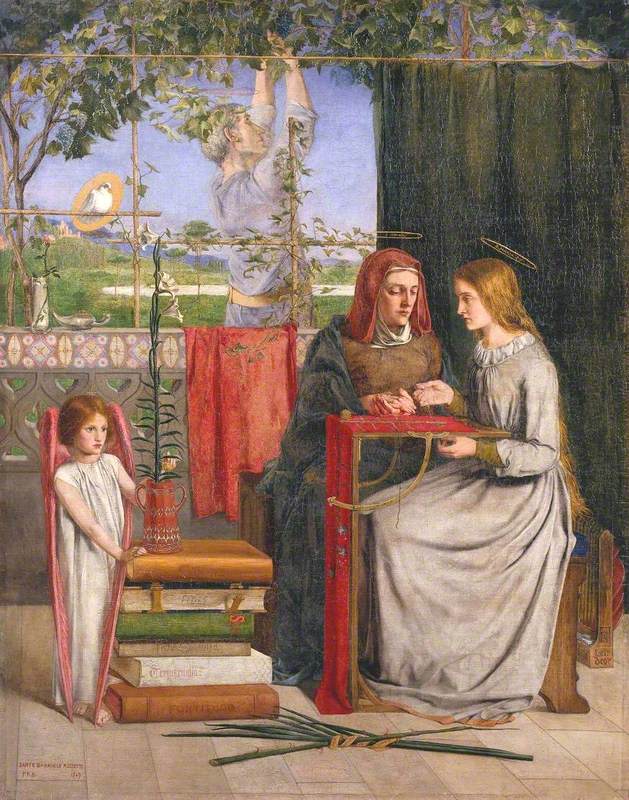

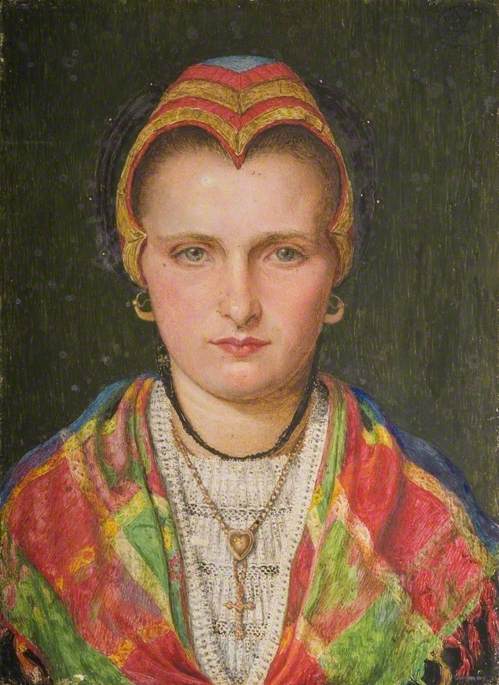

Rossetti was also a big fan of Keats, but his first Pre-Raphaelite painting took a religious story as its subject. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin is an imagined scene from the life of Jesus's mother, as recounted in the apocryphal Gospel of James (i.e. it's not in the Bible). Mary – on the right – is shown working on an embroidery with her mother, Anne. Rossetti used his sister Christina as the model for Mary, and his mother Frances as the model for Saint Anne. Mary's father, Joachim, is in the background pruning a vine.

Rossetti has packed the picture with symbolism – the palm branch on the floor, the thorny rose on the wall and the cross formed by the garden canes prefigure Christ's Passion, the lilies allude to Mary's purity, and the dove represents the Holy Spirit.

Almost incredibly, this wasn't just Rossetti's first Pre-Raphaelite composition, but his first completed oil painting of any kind. He displayed it not at the Royal Academy, but at a free exhibition on Hyde Park Corner. It's now in the collection of the Tate.

Holman Hunt, like Millais, exhibited his first PRB offering at the Royal Academy in 1849. It had the improbably long title Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and the Orsini factions – often known today just as Rienzi. It took its title and subject from a historical novel about a fourteenth-century Roman leader by Edward Bulwer-Lytton – Richard Wagner was also inspired by this work to write his 1842 opera of the same name.

Rienzi

1848–1849, oil on canvas by William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

The work is now in a private collection, but it's the first to show Holman Hunt's adoption of the PRB initials in his work.

The Brotherhood had made their first public foray into the art world, with their twin concerns of religious symbolism and the medieval world – but there had been little impact. They also tried to publish their own journal, called The Germ. However, it only ran for four issues in 1850 and was not a success.

One of the ideas behind the PRB was to keep it secret from the Royal Academy. So what happened next was not necessarily part of the plan.

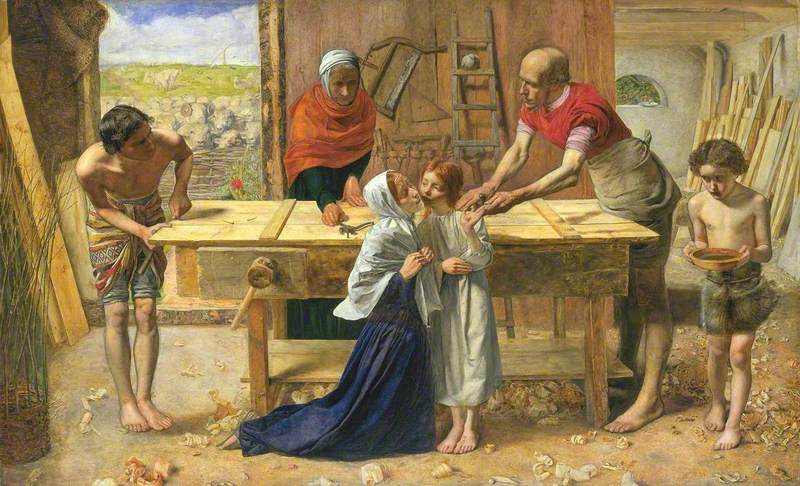

In 1850, Millais exhibited three works at the Academy. The first was a portrait of a man and his grandchild, the second took a theme from Shakespeare, showing Ferdinand lured by Ariel in The Tempest. The third was a religious subject, and this painting is today titled Christ in the House of His Parents. It's in the collection of Tate Britain.

Christ in the House of His Parents ('The Carpenter's Shop')

1849–50

John Everett Millais (1829–1896)

In the Royal Academy catalogue it was given no title, but instead has a quote from the Book of Zechariah:

'And one shall say unto him, What are those wounds in thine hands? Then he shall answer, Those with which I was wounded in the house of my friends.'

Like Rossetti's The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, it is packed with Christian symbolism, intended to be a deeply religious work. The wood and nails suggest the Crucifixion, and Jesus has cut his hand – the blood is on his hand has dropped to his feet, making a none-too-subtle stigmata. The boy on the right is John the Baptist, carrying water towards the injured Christ. The white dove on the ladder is a symbol of the Holy Spirit.

However, it was not well received, with no less than popular novelist Charles Dickens roundly criticising it. He said that Christ was 'a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed gown' and that Mary was ugly and looked like an alcoholic. The Times described the painting as 'revolting'. The critics of the work were objecting to Millais's depiction of the Holy Family as ordinary people, with some suggesting that it was blasphemous.

This must have been frustrating for Millais, who (as per the tenets of the Pre-Raphaelites of being true to nature) had intentionally used real people as his models – his father's head is that of Joseph (the body and hands are based on a real carpenter's), his sister-in-law was the model for Mary (she must have been mortified at Dickens's verdict), and the boys were real children he knew. Even the backdrop isn't imagined – Millais based it on a real carpenter's shop in Oxford Street – and the background sheep were modelled on sheep heads from a butcher.

So notorious was the painting that Queen Victoria asked for it to be transported to Buckingham Palace so she could have her own private viewing.

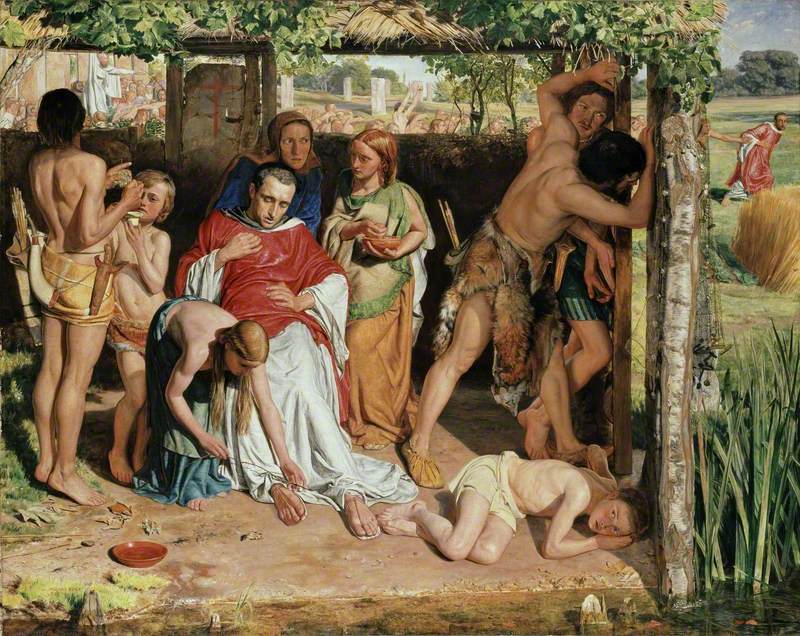

Alongside Millais's offering, in the same room at the Academy's exhibition, was a work by Holman Hunt. It was the snappily titled A converted British Family sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids, now in the collection of the Ashmolean, Oxford.

A converted British Family sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids

1850

William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

Supposedly set at some point when Britain was ruled by pagan Celts but there were Christian missionaries (it is unclear what time period Holman Hunt is imagining), a Christian family is hiding a priest from a crowd of heathens and druids in their hut by a river. In the background you can see the mob have already caught another priest, against the backdrop of a stone circle. The family's hut has a painted cross on a stone, and there are other symbolic allusions in the painting, just as in Millais's work.

The painting caused some controversy, although much less than that caused by Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents. This time the critics didn't like the contorted poses of the figures or the overall composition.

One man who did support the PRB at this time was John Ruskin, an established writer and critic who had previously championed the work of J. M. W. Turner. In May 1851 he wrote letters to The Times defending the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (although he himself did not like Millais's painting!). Ruskin was to become a firm supporter of the PRB and their ideals.

While Millais and Holman Hunt exhibited at the Academy, Rossetti once again exhibited a painting elsewhere. In April 1850 his Ecce Ancilla Domini! was on display at the Old Portland Gallery on Regent Street. It was bought for £50 in 1853 by Francis McCracken, and the Tate Gallery subsequently purchased it in 1886, where it remains in the collection today.

Rossetti's work is again unconventional. It depicts the Annunciation – the moment the Angel Gabriel reveals to the Virgin Mary that she will give birth to Jesus Christ – with Mary (modelled once again by his sister Christina) in a nightgown, in bed, having been woken by Gabriel (modelled by his brother William). Gabriel doesn't have wings, but flames at his feet – this was another point of controversy at the time. The negative reaction to this work led Rossetti to shun exhibiting his oil paintings for most of the rest of his life.

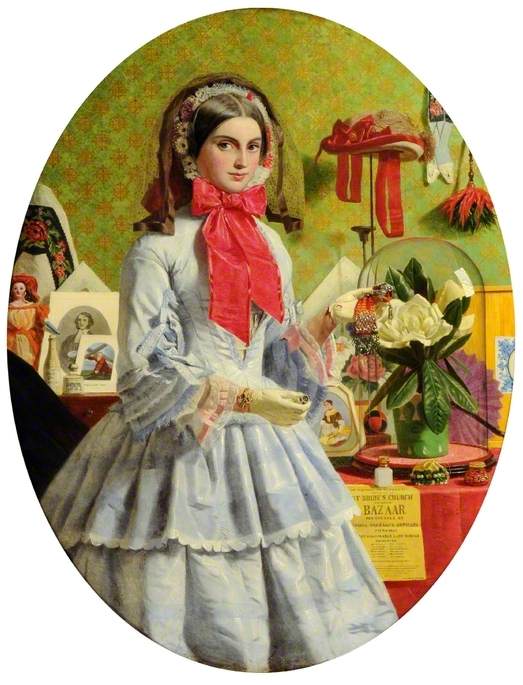

The backlash against the PRB was too much for one of them. James Collinson resigned from the Brotherhood – with the claims of blasphemy, he felt the movement was incompatible with his Roman Catholic faith. In 1852 he began training to be a priest, but had another change of heart and resumed his painting career a couple of years later. His most famous work is The Empty Purse, of which there are versions in the Tate collection, and also in Nottingham City Museums & Galleries and Sheffield Museums.

The Tate description of their version suggests the title of this picture (Nottingham and Tate's versions both reference the title For Sale) and the way the woman looks at the viewer means that she was a prostitute. Abandoning all thoughts of the PRB's ideals, Collinson's paintings like these show stories of everyday life with an explicit moral – exactly the sort of paintings against which the Pre-Raphaelites rebelled. He did keep his palette bright though, and the work is detailed, so some PRB ideas remained in his work.

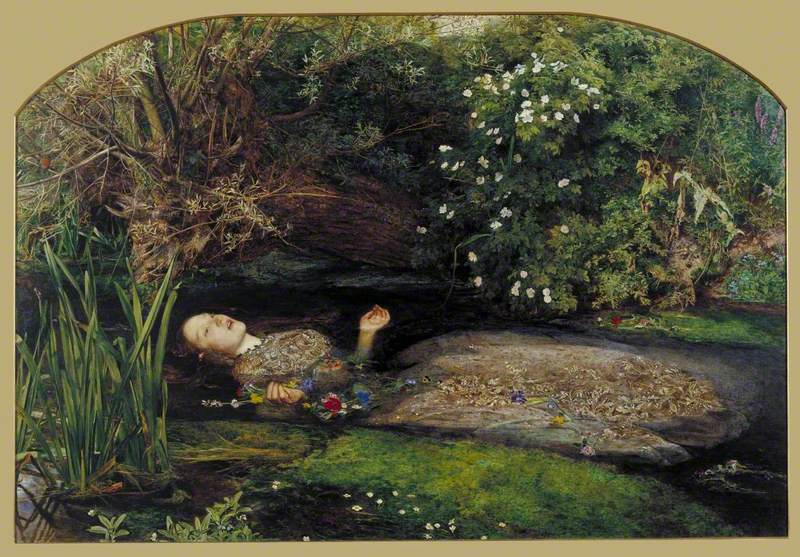

Undeterred by the reaction to his own paintings, Millais began work on what is today perhaps his most famous work, Ophelia. Depicting the character from Shakespeare's Hamlet before her death, it has come to epitomise the Pre-Raphaelite style. Today it is in the collection of Tate Britain.

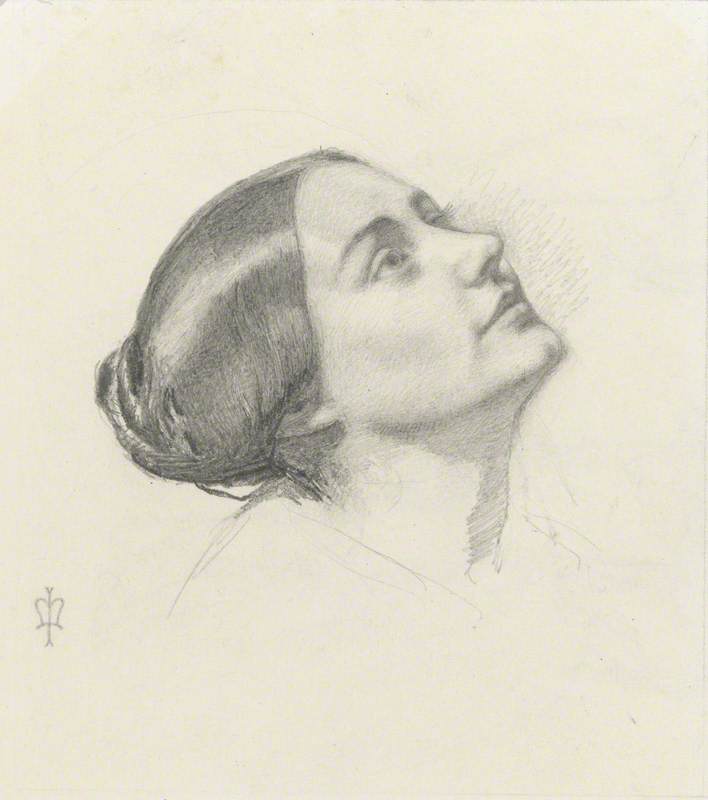

Millais created the work over some time, basing the river and natural world details on the Hogsmill River near Ewell in Surrey and, for Ophelia herself, having model Elizabeth Siddal lie fully clothed in a bathtub in his London studio. Famously, he forgot to keep the lamps burning under the bath and Siddal fell ill, with a cold or pneumonia.

Siddal had met Rossetti in 1850, and she became his primary muse over the following decade – they eventually married in 1860, but she died after an overdose of laudanum in 1862. She was also a model for various painters in their circle. She was, however, an artist in her own right – as were many of the women associated with the Pre-Raphaelites.

Millais's Ophelia was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852, but the previous year he had exhibited three works – Mariana (also in Tate Britain today), The Woodman's Daughter (in the City of London's Guildhall Art Gallery), and The Return of the Dove to the Ark (in the Ashmolean, Oxford).

Mariana is a depiction of a character from Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, but the narrative is from a poem based on the play, written by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who had been made Poet Laureate in 1850. Tennyson was – like Keats – one of the PRB's favourites, as he often wrote poetry inspired by the medieval world. The painting was exhibited without a title and instead with lines from the poem.

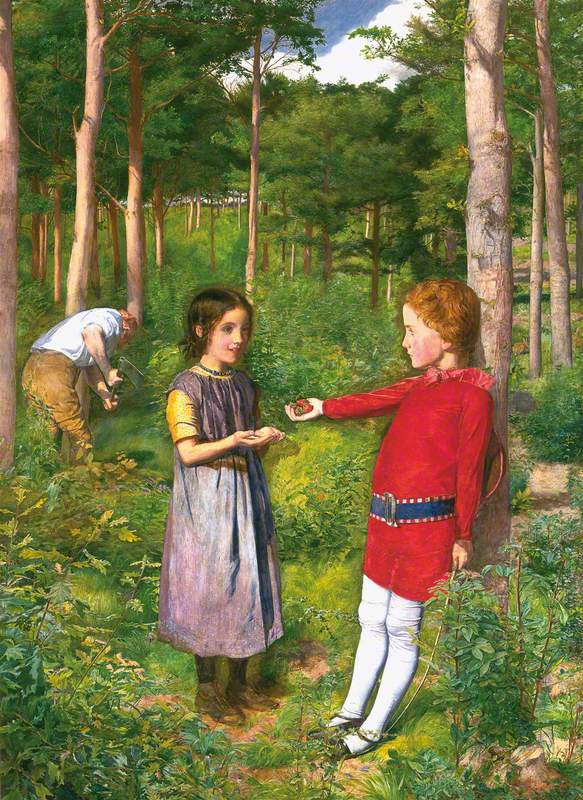

The scene from Coventry Patmore's poem The Woodman's Daughter (published in 1844) was likewise displayed with two stanzas of the poem.

The ark picture depicts the moment in the Biblical Book of Genesis when the Great Flood is over, and Noah and his family have been spared – the dove has returned with an olive sprig.

It was originally intended as part of a larger work that was never realised. Ruskin wanted to buy it, but it had already been sold to art collectors Martha and Thomas Combe. They hung it next to two of their other purchases – Holman Hunt's A converted British Family sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids (see above) and Convent Thoughts by Charles Allston Collins, who was associated with the Pre-Raphaelites but was not a member of the Brotherhood.

In the same year, Holman Hunt exhibited Valentine rescuing Sylvia from Proteus at the RA. Based on a scene from Shakespeare's Two Gentlemen of Verona, it's now in the collection of Birmingham Museums Trust.

Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus

1851

William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

The detailed rendering of the four foreground figures' clothes – as well as the leaves and trees of the forest – are typically Pre-Raphaelite.

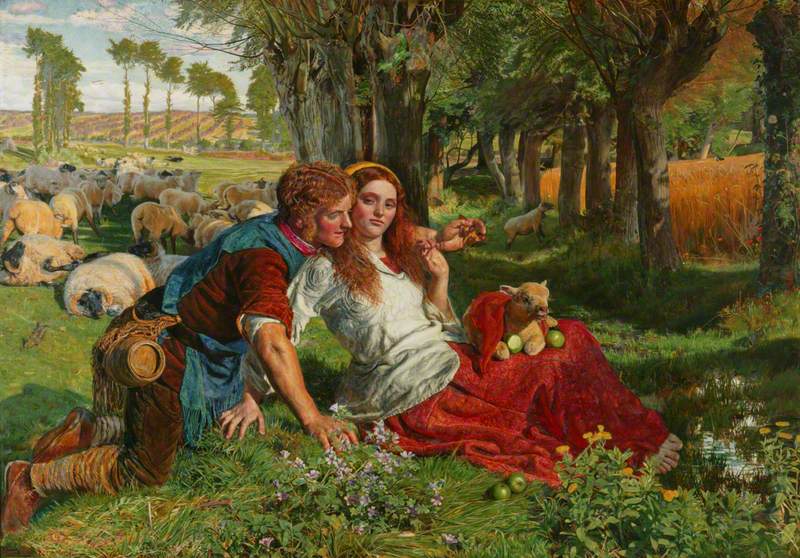

At the Academy the following year, in 1852, Holman Hunt exhibited The Hireling Shepherd, now in the collection of Manchester Art Gallery.

Once again, the detail in this bucolic idyll is particularly striking, with the grass, trees and sheep all finely painted. It's likely that Holman Hunt intended a hidden meaning about Christian flocks going astray, although at the Academy it was accompanied by lines from Shakespeare's King Lear.

The PRB works on display were not universally acclaimed at the time, and it seemed only a few key figures like Ruskin were supporting their aims. The Brotherhood had already been shaken by one resignation, but what happened next was to destroy it.

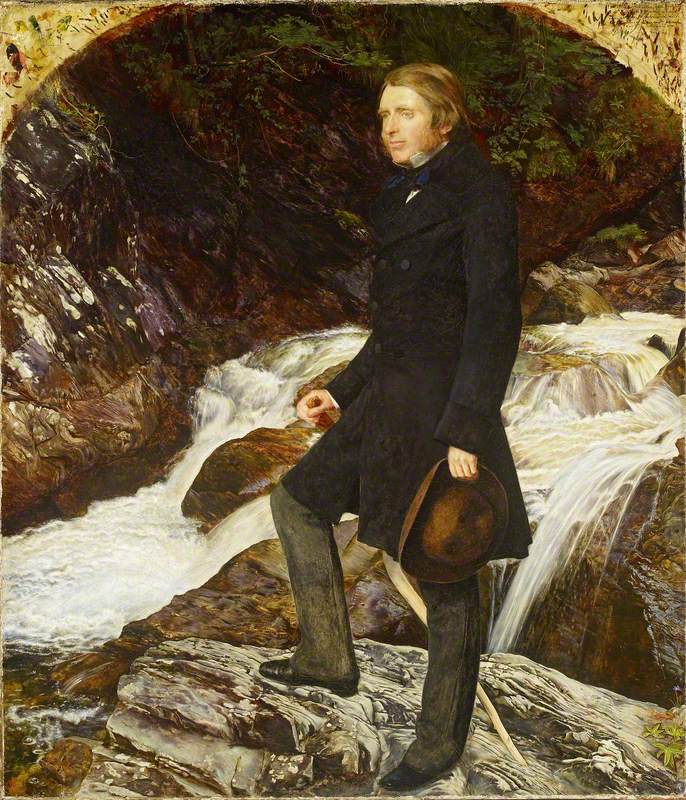

Millais continued to court John Ruskin's patronage, and they made a trip to Scotland in 1853, ostensibly to undertake a portrait – here it is in the collection of the Ashmolean.

However, Ruskin brought his wife, Euphemia Gray, known as Effie. She and Millais grew closer and ultimately the Ruskins' marriage was annulled (due to non-consummation). Millais then married Effie, which resulted in a huge scandal, which you can read more about in this story.

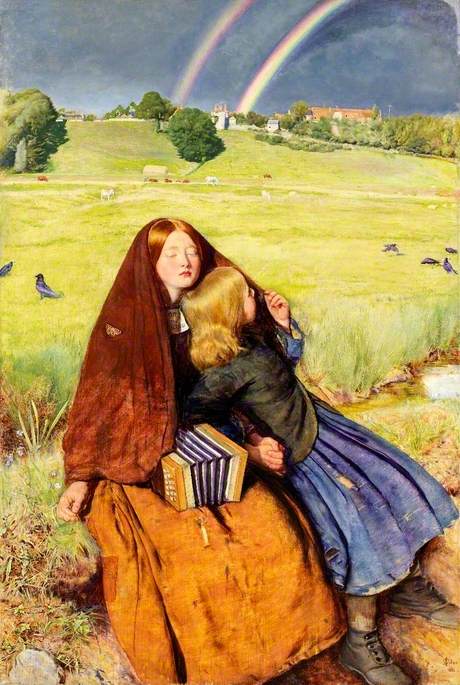

After his marriage, Millais moved away from the ideals of the Brotherhood, and began to paint in a much wider style. This included works such as Autumn Leaves (Manchester Art Gallery) and The Blind Girl (Birmingham Museums Trust), neither of which appear to have an overt link back to poetry, literature or religion.

Millais also painted portraits of eminent Victorians, such as the Prime Ministers Disraeli and Gladstone, as well as Cardinal Newman.

Ruskin, perhaps understandably, attacked his later works, while remaining supportive of Holman Hunt and Rossetti.

For many in the Pre-Raphaelite circle, Millais was a sell-out. His later works grew in popularity with the public and he even allowed his work to be used in a soap commercial.

Perhaps the ultimate irony came as he became (in the final year of his life) President of the Royal Academy. The young firebrand was now transformed – he was Sir Joshua's successor...

Meanwhile, Rossetti spent most of the rest of the 1850s concerned with poetry and went further toward the medieval aspects of the PRB's ideals. He began to associate with other artists such as Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris who encouraged him to continue in this vein, and this second wave of artists also became linked to the name 'Pre-Raphaelite', although they were not part of 'the Brotherhood'.

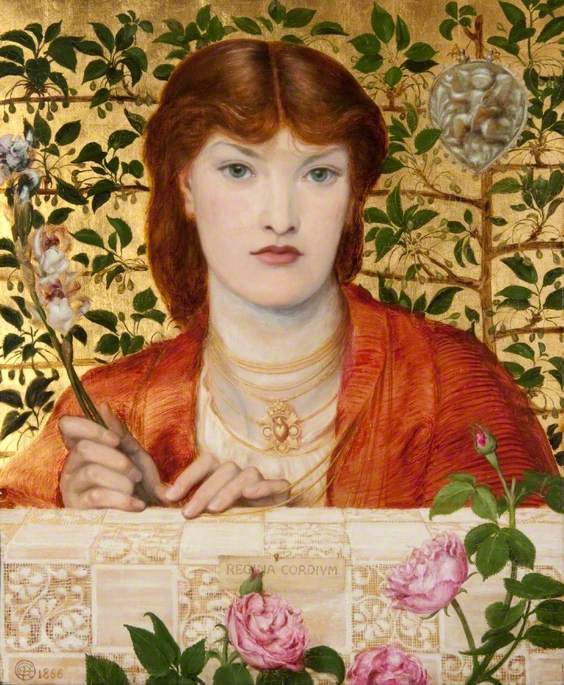

Rossetti's own later works included some of his most famous today – a succession of women with serious expressions and long flowing hair. They are largely based on the High Renaissance works of artists such as Titian and Veronese, and so are another move away from the PRB's original intentions.

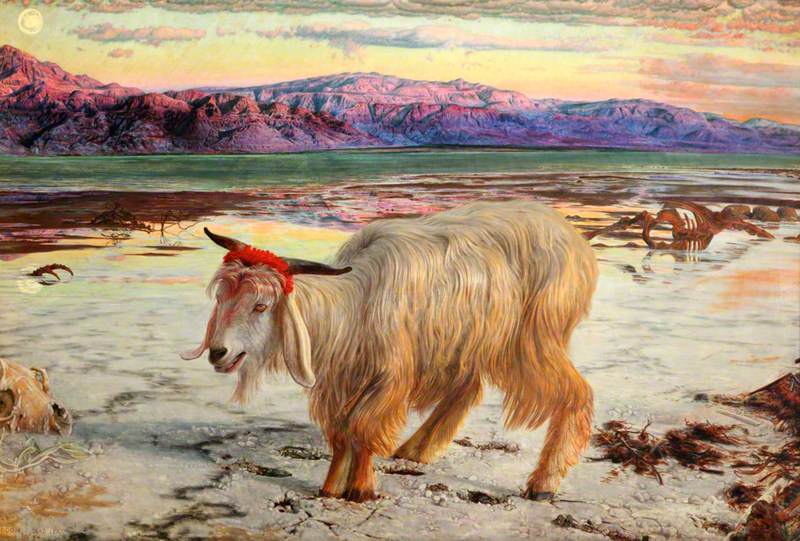

As the original Brotherhood disintegrated, Holman Hunt kept working on his style, becoming ever more entranced by his Christian faith and the symbolism of the Church. He went to the Holy Land in the mid 1850s, painting in Jerusalem and picking up an even brighter colour palette. Some of his most famous works date from this slightly later period, including The Scapegoat and The Light of the World – both of which are in collections across the UK in various versions.

The Scapegoat is deeply symbolic, referring to the animal described in the Book of Leviticus which had its horns wrapped in a cloth on the Day of Atonement. The cloth represented the sins of the people and the animal would be driven off, cleansing the community. The versions in Manchester Art Gallery and Lady Lever Gallery were created at the same time. The smaller Manchester version has a noticeably more vivid colour scheme.

The larger version is the one that was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856.

The first version of The Light of the World is in Keble College, Oxford and it depicts Jesus lighting the way, about to knock on a door that looks overgrown with plants. It alludes to a passage from the Book of Revelation.

A later version toured the world between 1905 and 1907 and is now in St Paul's Cathedral in London.

Today Millais has over 170 works in UK public collections, Rossetti has over 70 in different mediums, and Holman Hunt just over 60 works. Of the other artists in the original Brotherhood, Thomas Woolner has nearly 100 sculptures, F. G. Stephens has just three (all in the Tate collection), and Collinson has nine paintings (although three of them are variations on the same composition).

Although all three of the main artists in the original PRB went their separate artistic ways, the name 'Pre-Raphaelite' became associated with a new group of artists, who ultimately worked into the twentieth century – a lasting influence on British art.

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK