Before feminism gained momentum in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there was the Bluestocking Society, an eighteenth-century literary group run by aristocratic and brilliant women of the day.

Often defined as radical for being the first female-led group to champion the careers of other women, in many ways the group was, in fact, rather conservative in its initial aims.

The Bluestockings defined themselves by what they were not, standing against the debauched hedonism of eighteenth-century high society that encouraged excessive drinking, gambling, and idle tittle-tattle. They regarded themselves as virtuous proponents for the art of refined and intellectual conversation, usually over tea drinking.

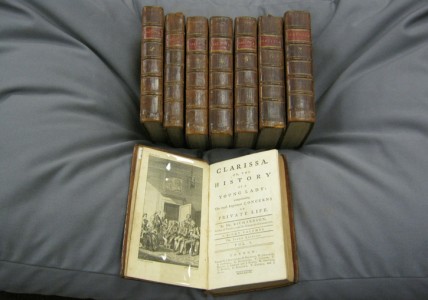

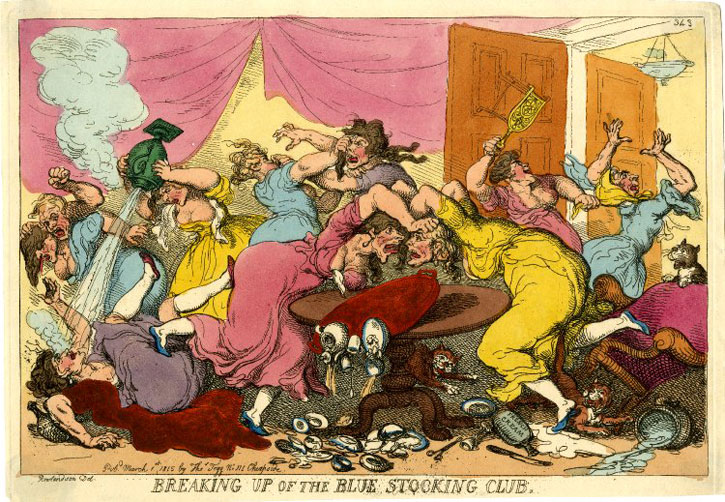

Breaking Up of the Blue Stocking Club

1815, hand-coloured etching on paper by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)

But why did the Bluestockings become a pejorative term by the late eighteenth century? And moreover, why has the group, regarded by some as the foremothers of modern feminism, been so overlooked?

Modern muses

When the Bluestocking Society was initially founded in the 1750s, its members represented a new kind of modern, intellectual women, who were accomplished and well-versed in many fields – artistic, literary and political.

Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo

1778

Richard Samuel (d.1787)

In this painting found in The National Portrait Gallery by Richard Samuel, the leading Bluestockings are portrayed as the nine muses, who in Greek mythology were the daughters of Zeus – each presided over a different art.

On the left, the painting features artist Angelica Kauffmann at her easel, in front of the writers Elizabeth Carter and Anna Barbauld. At the centre of the composition stands the singer Elizabeth Sheridan (née Linley). To the right stands the writer Charlotte Lennox, the historian Catharine Macaulay (holding the parchment), writer and abolitionist Hannah More and the novelist Elizabeth Griffith (holding the tablet).

The co-founder and matriarch of the Bluestockings, Elizabeth Montagu, sits in the middle on the right-hand side.

In Greek mythology, the muses and their arts were Clio (history), Euterpe (music), Thalia (comedy), Melpomene (tragedy), Terpsichore (dance), Erato (love and poetry), Polymnia (sacred poetry, hymn and dance), Ourania (astronomy), and Calliope (epic poetry).

The art of conversation

The art of 'rational' conversation was one of the principal aims of the Bluestockings. But what did 'rational' mean in the eighteenth-century context?

A product of Enlightenment thought, to be 'rational' referred back to the philosophical enquiries of classicism and the Renaissance. In the eighteenth century, the classical world was idealized. The art of refined, intellectual and rational conversation was about more than just proper and polite sociability. It was regarded as a form of moral improvement, a way of promoting 'civic virtue'. The Bluestockings were fighting against social norms amongst aristocratic circles – gossip and shallow conversation stereotypically attached to women at that time.

The group's attitude towards conversation was epitomised in the 1787 poem by Hannah More, aptly titled Conversation.

The founding members

Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800) and Elizabeth Vesey (1715–1791) were the founding members of the Bluestocking Society, although many of the early salons also took place in the home of Frances Boscawen. Often perceived as being a group exclusively for women, the Bluestockings, in fact, were always open to male members. The botanist and writer Benjamin Stillingfleet and influential literary figure Samuel Johnson were central figures in the group. Other salon guests regularly included Joshua Reynolds, Horace Walpole and Edmund Burke.

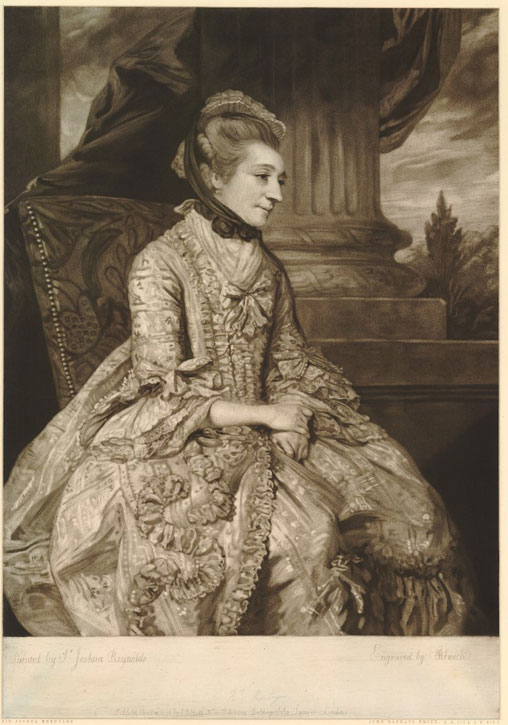

Mrs Montagu (after Joshua Reynolds)

1776, mezzotint on paper by John Raphael Smith (1752–1812)

Significantly, Montagu was the richest woman in England, who was born into gentry but married into aristocracy when she was betrothed to Edward Montagu. A formidable character and celebrity in eighteenth-century society, she was named 'Queen of the blues' and was regarded as the leading lady of the Bluestockings, harnessing the power of her social connections and witty repartee.

Elizabeth Vesey

c.1770, black crayon with touches of sepia and grey wash by unknown artist

Irish-born poet and scholar Vesey, was a close friend to Montagu who established an even more informal salon at her London home. She was renowned for her slender figure, flirtatious nature and unassailable charm. Her nickname was 'Sylph', referring to a mythological air spirit.

In 1781, Montagu wrote a letter to Vesey, in which she stated: 'We have lived the wisest, the best, and the most celebrated men of our Times, and with some of the best, most accomplished, most learned Women of any times.'

Mary Delany

One of the earliest members of the group was Mary Delany (1700–1788), an artist and letter writer, and friend to the Baroque composer George Frideric Handel.

Delany was infamously against the strict traditions of marriage, once proclaiming: 'Why must women be driven to the necessity of marrying? A state that should always be a matter of choice!'

Elizabeth Carter

Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806) was an influential writer, poet, classicist and polymath who was an important member of the Bluestocking circle. She famously translated the work of Stoic philosopher Epictetus.

Catharine Macaulay

Catharine Macaulay, née Sawbridge

c.1775

Robert Edge Pine (1730–1788)

Catharine Macaulay (1731–1791) was the first female historian in Britain (and one of the first in the world), who published the book History of England from the Accession of James I to that of the Brunswick Line (1763–1783).

Hester Thrale

Hester Lynch Piozzi, née Salusbury, Later Mrs Thrale

1785–1786

unknown artist

Hester Thrale (1741–1821) who was later known by the name of her second marriage 'Piozzi', was a Welsh-born author and patron of the arts. Like many of the Bluestockings, she was very close to Samuel Johnson, publishing the controversial bestselling Anecdotes of the late Samuel Johnson in 1786, which caused a stir amongst other members of the group. Horace Walpole condemned her for the publication, comparing it to a 'heap of rubbish'.

Anna Seward

Showing signs of talent from a young age, Anna Seward (1742–1809) was a published poet by the time she was a teenager.

Allegedly her father (also a poet) did not want her to become a 'learned lady' and tried to squash her passion for poetry. Nevertheless, Seward became successful and a member of the Lunar Society, an informal dinner club of notable Enlightenment figures who met regularly outside of Birmingham. Like many other ambitious, literary female figures of her time, she received backlash. She too was criticised by Walpole, who claimed she had 'no imagination, no novelty'.

She famously eschewed marriage and sexual love, proclaiming that friendship was superior to other relationships. Many have speculated that she was gay.

Hannah More

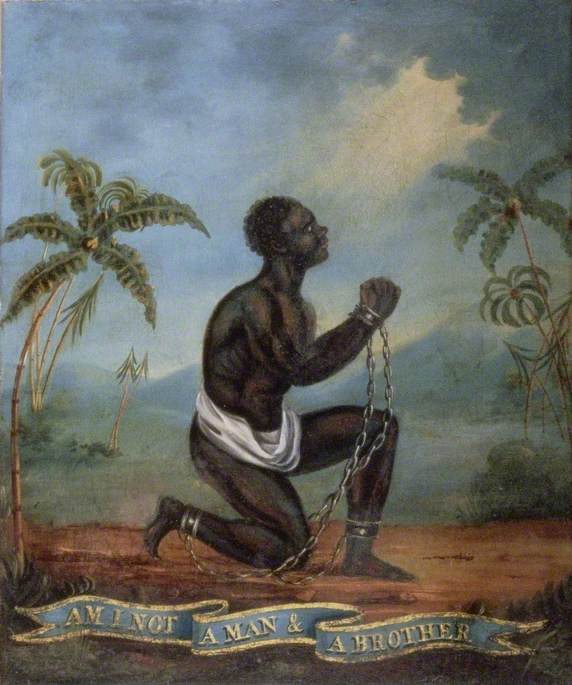

A second generation Bluestocking member, Hannah More (1745–1833) was a famous poet, playwright, education reformer and abolitionist.

She publicly campaigned against the slave trade and established and published the widely successful Cheap Repository Tracts – a series of literary tracts that intended to educate the general public on religious and political matters.

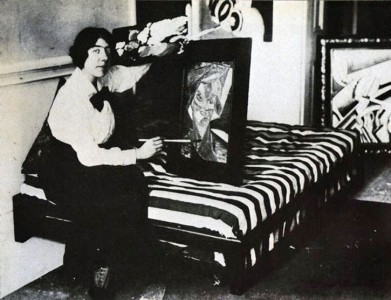

Fanny Burney

Before Jane Austen, there was Fanny Burney (1752–1840) a prolific novelist, playwright, and diarist whose satirical fiction was widely read. Burney's novels were trailblazing, in that they were written from the perspective of a woman, by a woman.

Frances d'Arblay ('Fanny Burney')

c.1784–1785

Edward Francis Burney (1760–1848)

In 1778, she published her first novel Evelina anonymously. The humorous book is a portrayal of a young woman navigating eighteenth-century polite society. Burney satirized the Bluestockings in her unpublished play The Witlings (1779), in which she portrayed Montagu as a character called 'Lady Smatter'. Upon the advice of her father, who feared the play would greatly offend Montagu and the Bluestockings, Burney never published the play. For a woman, to write comedy, let alone make a living off her pen, was unheard of.

Nevertheless, Burney's humorous work would greatly influence her near contemporary, Jane Austen. In Austen's Pride and Prejudice, the tense dialogue between characters Caroline Bingley and Elizabeth Bennet perhaps touched upon society's conflicting opinions about women's intellectual and creative capabilities. In Chapter 8, Bingley questions: 'Are you so severe upon your own sex as to doubt the possibility of all this?' to which Elizabeth replies 'I never saw such a woman. I never saw such capacity, and taste, and application, and elegance, as you describe united.'

Austen was undeniably pointing out that social class was what enabled some aristocratic women to be considered 'accomplished', whereas others (those belonging to the same lower class of Elizabeth) were less accustomed to witnessing impressively accomplished women.

Elizabeth Ann Linley

Elizabeth Ann Sheridan (née Linley) (1754–1792) was a celebrated singer, poet and writer who was famed for her beauty. She was painted several times by Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough and became involved in the Bluestocking society.

Elizabeth and Mary Linley

c.1772 (retouched 1785)

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

Despite the many accomplishments of the Bluestockings, who arguably set new precedents for women, by the 1790s the public's perception of the Bluestockings had shifted drastically.

This was illustrated by Thomas Rowlandson's famous etching, Breaking Up of the Bluestocking Club (which you can see at the top of this piece). The satirical work depicted the group as brawling women in a vicious catfight, any remnants of sisterly solidarity removed. Misogynistic slander towards the group became commonplace by this decade, and the term 'Bluestocking' had acquired negative connotations, becoming synonymous with 'frumpy' or 'fishwife'.

Romantic literary figure William Hazlitt once said: 'The bluestocking is the most odious character in society... she sinks where she is placed, like the yolk of an egg, to the bottom, and carries the filth with her.' Other Romantic male figures such as Lord Byron and Samuel Coleridge also ridiculed the Bluestockings.

With historical hindsight, we can reconsider the remarkable accomplishments of the Bluestockings, who certainly paved the way for other women to prosper and be seen as intellectual equals to men. Like many other movements and watershed moments in women's history, they were not immune to a vitriolic backlash, though today their legacy as brilliant women with unashamed aspirations can be celebrated.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK