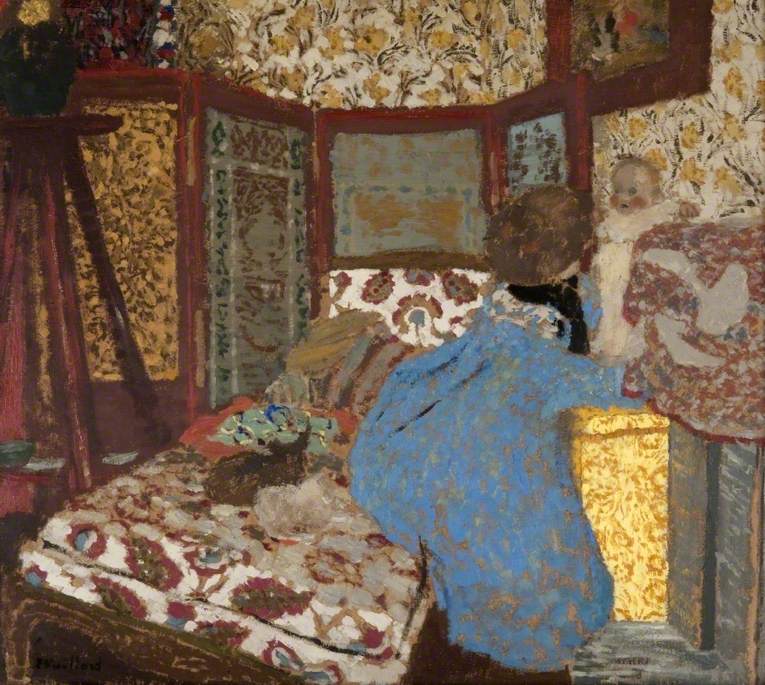

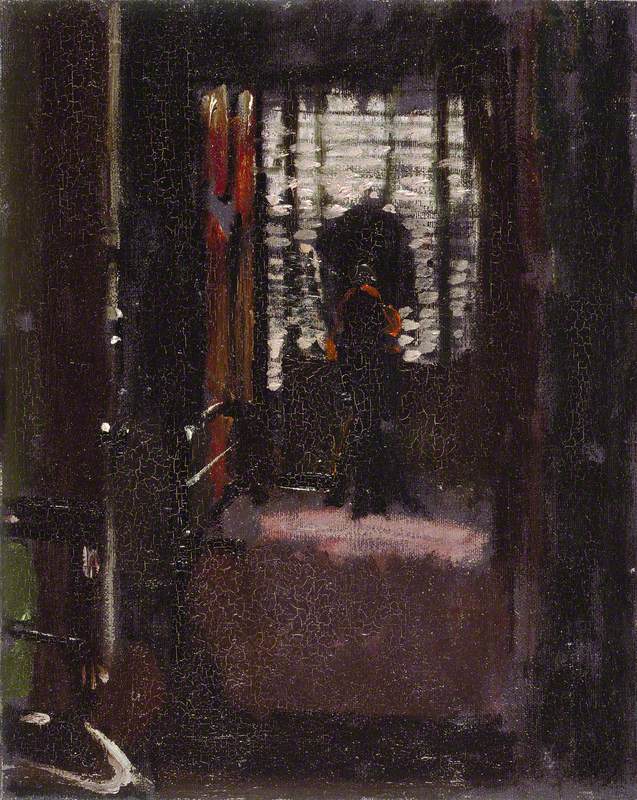

A woman in a military-style buff jacket with distinctive, wide, placketed, buttoned-back cuffs and large black buttons double-breasted to the front; a neat, plain white collar with a soft black silk bow to the neck. Her hooped, softly pleated skirts swell out hugely at the back, characteristic of European styles from about 1860 to 1865. She wears a broad black silk sash similar to a man's cummerbund, with a hint of a bow behind. The outfit is neither conventional nor staid. Its innovation declares the wearer to have a mind of her own.

What might be a wide, large black net shawl of some description, with a simple pattern of large black spots worked into its gauze, is draped across her skirt fronts. Since the skirt is cropped one can only deduce the length, width, or even purpose of this delicate stuff. The woman's black hair is simply and elegantly dressed, evidently by a maid, for from the quality and stylishness of her garments, the woman is upper class.

Her thick black hair, which appears to be her own, is centrally and severely parted and pulled back in wings over her ears, then coiled in thick braids in a low chignon on the back of her head and down to her nape, perhaps smoothed with a fine net. The style sets off her sallow skin, pale lips and shadowed eyes in a bold and striking face.

But even though the painting, done by a young male painter of a beautiful younger woman, is fairly faithful to the photo it was based on, all is not precisely as it seems.

The woman holds an unusual item that is difficult to identify but which appears to be a type of poke bonnet with a gentle flounce to frame the face, enlivened with puffs of unidentifiable plumage at the back, with long wide black silk ribbons to tie it under the chin in a dashing bow, probably knotted to one side. While it is likely that this is what it is, the curious way it has been painted indicates that the painter is not completely certain of its structure or actual shape when worn.

The flourish of his signature, appearing almost as two jaunty smaller red bows on the bonnet, adds by far the brightest colour in the composition.

An inspection of the jacket, of the seams sketched in with a quick, wavering, yet sure line done with a brush of blackish paint at shoulders and at bust, and again to mark the wide cuff openings of the jacket sleeve (where the marks are not quite so certain, and make a slight structural error; though this appears to be due to speed), show that the painter was familiar with the cut of women's clothes and sufficiently interested in them to indicate such details correctly.

The woman wears no jewellery, which is striking at this period, although her ring fingers are not visible, so one cannot tell whether she is single or not. The background appears to be a stylised, smart floral wallpaper, quickly drawn on a curious greenish-yellow, possibly arsenic-based coloured ground, that echoes the colour of the woman's skin.

The French painter's name was Edgar Degas, born 1834; and the Hungarian sitter's name Princess Pauline von Metternich, born two years later in Vienna in 1836. These are known facts. As is the approximate date of the painting, around 1865; and that it is closely based on a photograph of Pauline and her husband, who was also her uncle, Richard Metternich, Austrian Ambassador to Paris during the Second Empire. The photograph was taken by society photographer André Disdéri, in 1864.

But even though the painting, done by a young male painter of a beautiful younger woman, is fairly faithful to the photo it was based on, all is not precisely as it seems.

Degas had met Manet in 1862, and the impressionist quality of his fast but light and sure brushwork; his handling and simplifying of the subject, are evident.

Pauline von Metternich was born Countess Sandor von Slavnicza. Aristocratic Pauline did not consider herself beautiful, as her memoir makes clear; but she liked smoking cigars and was intelligent and lively in company. It has been recounted that she would lift her skirts – presumably to avoid mud when getting in or out of carriages – but this, associated with contemporary attitudes towards showing ankles, was considered racy.

Musically and socially gifted, she was also passionate about clothes and style. She described her dresses and outfits, whether for balls or more pedestrian events, in detail in her memoirs. By her own account, she brought the couturier Charles Frederick Worth to the attention of the Empress Eugénie, by wearing a Worth dress to a ball at the Tuileries Palace.

During an unexpected visit, Worth's wife, Marie, had told the princess that her husband wished to make two dresses for her. One was a huge crinolined white tulle dress with silver spangles and light floral embroidery, which would have looked fresh and youthful – albeit adorned with an added sash of diamonds. It is no surprise that it caught the Empress's eye.

And the outfit Pauline wears in Degas's painting was also designed by Worth, who became the princess's favourite dressmaker. However, one must look at the photograph to be certain of its detail. Several interesting things emerge. For one thing, for her photograph, Pauline actually wore a dress of one principal colour: a pale hue, perhaps deep cream or pale lavender, one cannot tell. But for reasons of his own, Degas turned it into a skirt and jacket. Existing variants of the photo session, studies for a carte de visite, show that she was photographed wearing that dress in several different poses.

One sees in those pictures that, to echo the cuffs, the skirts had a bold, unusual and deep border of about 30 cm in a motif that resembles piano keys. A dark waist ribbon, tied at centre back with long trailing ends, picks this up. However, there is no gauzy shawl laid over the skirts.

She was about 28; Degas 30; and both of them dark and broodingly handsome.

But in the version Degas worked from, which is probably but not necessarily from the same session, Pauline stood with her husband, her left arm hooked into his elbow. That version shows what is evidently her shawl draped over the skirt of her dress, perhaps a sudden inspiration by the photographer, perhaps by the princess. One also sees that the shawl has a much more complex pattern woven into it, of sheer paisley motifs. Degas therefore deliberately simplified it into large spots for his painting.

One sees too that her neck bow was actually a tartan or tarlatan pattern, which again, Degas simplified to plain black. And his decision to turn her dress into a two-piece outfit of skirt and jacket, has been noted. Degas had met Manet in 1862, and the impressionist quality of his fast but light and sure brushwork; his handling and simplifying of the subject, are evident. The immediacy, certainty and indeed intimacy of this portrait are absolutely arresting.

The Metternichs were in Paris for eleven years until the end of the Second Empire, when they had to return to Austria. During that time, although young Degas may not have moved in quite such illustrious circles, he was haute bourgeoise and well off, so it is more than likely that he would have seen the princess on at least one occasion and, one imagines, admired her unique, modern style – which he, as noted simplified and modernised further. Even a cursory inspection of Degas's oeuvre, particularly in his paintings of the painter Mary Cassatt, demonstrates his keen observation of her clothing.

Perhaps it was having some knowledge of the princess that gave this fast, sketchy painting its immediacy and vividness. For Pauline does not appear to have been drawn from a photo, even though we can see that that is indeed the case. She seems to live. Those deep shadows under the eyes, that sideways glance from eyes made less tonally intense, and so more intriguing, than in the photo; the sensual, pale lips.

An intensely fashionable and ultra-modern woman of mysterious appeal with a beautiful figure. A worthy heroine in a novel by rising young literary comet Zola, perhaps. She was about 28; Degas 30; and both of them dark and broodingly handsome. Why did Degas take Pauline's husband out of the composition entirely, and sketch and paint this lovely woman on her own, with such attentive vigour and dash?

Philippa Stockley, author, award-winning journalist, and exhibiting painter