Art UK is undertaking a project to record murals across the country. You might have seen a mural 'in the wild' but perhaps haven't noticed it, so here's a quick start guide to the art form.

What is a mural?

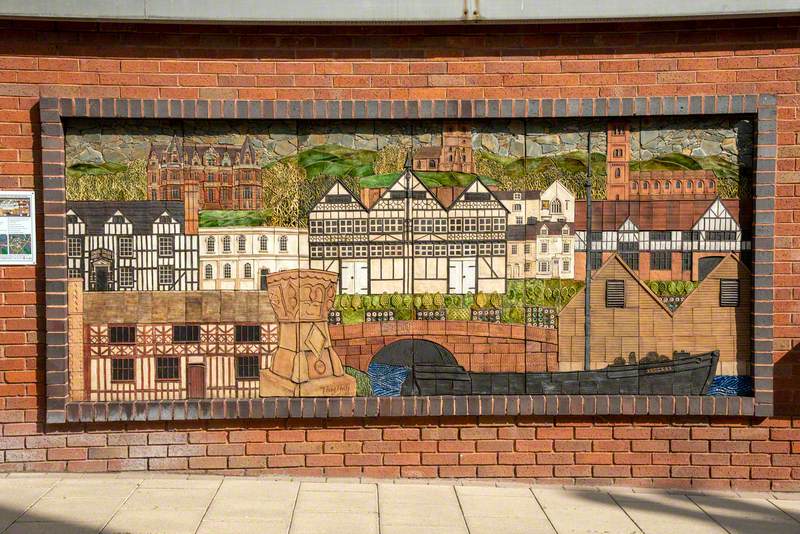

Murals are artworks executed directly onto a wall and can be created in a variety of materials, including paint, concrete, brick, wood, stone, ceramic tile and other materials.

Murals can be flat two-dimensional artworks, especially those created in paint, but they can also be three dimensional and described as reliefs, friezes or sculptures.

Public painted murals are an accessible and immediate artwork that have increased significantly in recent years and have risen in profile as towns and cities embrace ways to inject colour and life back into urban areas struggling to find a new identity. Often able to respond within days of world events, such as the death of Elizabeth II, murals are becoming a barometer of the social conscience, immediately celebrating or mourning events, and allowing and validating the self-expression of communities.

Painted murals can be a more cost-effective way for people and communities to celebrate their local history and notable people, than raising funds to create a sculpture or other sculptural monument.

Captain Edward Smith (1850–1912)

2023

Ethan Lemon and We are Culla

Contemporary street art has become extremely popular in recent years. The term street art may typically make us think of art that is created without official permission but, despite the origins of some forms of street art in graffiti, much street art is now often sanctioned or commissioned. Although many forms of street art developed from graffiti, the main difference between the two is the intention and the audience.

Kendall Road Folly Murals 2

2023

Simon Collins (active since 2008)

Graffiti is primarily a word-based art that emerged in inner-city neighbourhoods as a way for urban youth to express themselves and their presence. Graffiti tags (words, names and symbols) are a form of branding and a way of marking territory. This type of art is not necessarily designed to be understood or interacted with by a wide audience but is intended to be seen by other graffiti artists. Street art, on the other hand, is made to connect with a wide audience putting across a message to them or simply providing something beautiful for everyone to enjoy.

Many cities have a wealth of artists creating striking murals, often under the authority of the local council or the owners of the properties. Towns and cities with an abundance of street art include Glasgow, Bristol, Manchester, Cardiff, Belfast, Aberdeen and Sheffield.

Child Climbing up Building

2018

Ernest Zacharevic (b.1986)

Although many murals have been demolished or removed in recent years, many still survive, especially those produced in Britain between the 1940s and 1980s, which saw an increase in murals created as part of post-war reconstruction and the building boom. Historian Lynn Pearson describes these murals as 'art for the people – not always popular, sometimes controversial but often valued'.

Coventry Market Mural

early 1950s

Dresden Art Students (active early 1950s)

Where can murals be found?

Murals are found in all parts of the UK. They are located on the outside and inside of buildings and in public spaces, such as shopping centres, railway stations, subways, churches and museums.

Stoke-on-Trent Railway Station Murals

1994

Liz Kayley (active 1994) and Johnson Tiles (founded 1901)

They can also be found on more unusual surfaces, such as bollards and electrical supply boxes.

Northern Ireland has a rich history of mural painting that is very different to other parts of the country. In the past, the majority have been paramilitary murals, painted as propaganda and to mark territory in urban areas.

The Bloody Sunday Commemoration

1997

Kevin Hasson (b.1958) and Tom Kelly (b.1959) and William Kelly (1948–2017)

More recently, there are a growing number of cultural murals and street art being created in Northern Ireland, including commissioned, legal works. A programme of re-imaging of painted murals is being undertaken with the cooperation of local organisations and communities.

Are murals at risk?

The location of murals, the circumstances behind their creation and the materials used to create them can result in this type of artwork being ephemeral in nature. Buildings and housing estates are demolished to make way for new developments meaning that many murals have been lost.

All outdoor artworks are at risk from the elements and are especially susceptible to damage from water and light. Murals are at risk from deliberate and accidental damage, structural or mechanical deterioration (cracks, dents, spalling, movement), vandalism, graffiti, weathering, atmospheric pollution, tree sap, bird droppings, damp, inappropriate conservation treatments, and from the building or wall they are attached to being demolished or remodelled.

Murals made from ceramic tiles and concrete are more robust, but outdoor painted murals, as semi-permanent artworks, are at greater risk from the weather or being painted over. Many are only designed to be extant for a short time. The Twentieth Century Society's Murals Campaign was set up to highlight that many murals from the post-war period survive and that although listing will be an option for only a small number of them, many more deserve to survive.

Indoor murals are also at risk. Churches Conservation Trust have told us that as well as the physical threats to murals, such as vandalism and accidental damage, environmental factors are very difficult to control in historic churches. Their churches are monitored and have measures in place to control the temperature and light, but interior environments can be unstable.

The main risks to wall paintings and other delicate elements of church interiors are flooding and the increase of lead thefts. Loss of part of the church roof or water ingress cause environmental damage and accelerate detrimental climate conditions which can damage wall paintings within 24 hours.

Local Life 1890–1910

c.1986–1988

Kenneth George Budd (1925–1995)

Mural artists

Pre-twentieth-century mural artists are more likely to be anonymous, but many more recent murals are often been created by well-known artists.

Artists who are well known for creating murals include the following:

William Mitchell (1925–2020)

William Mitchell was an English sculptor, artist and designer, best known for his large-scale concrete murals and public works of art from the 1960s and 1970s. His work is often of an abstract or stylised nature, with heavily modelled surfaces.

Federation House Concrete Reliefs

c.1965–1966

William Mitchell (1925–2020) and Gilling Dod Architects

Many of Mitchell's extant works in the UK are now being recognised for their artistic merit and contemporary historic value. Sixteen of Mitchell's murals and sculptures have been granted Grade II listed status, including a Brutalist Climbing Wall under Hockley Flyover, Hockley Birmingham built in 1968 and Scenes of Contemporary Life, a two-part mural at the Park Place underpass in Stevenage, Hertfordshire.

Philippa Threlfall (b.1939)

Philippa Threlfall has been making relief murals in ceramic since the 1960s. Together with her husband and partner Kennedy Collings, she has completed over one hundred major works on sites all over the UK and overseas. Some were made for private clients, but most were commissioned for display in public spaces - shopping precincts, banks, building societies, an airport, hospital and office developments.

Peoples Who Used the Essex Road

1969

Philippa Threlfall (b.1939)

Henry Collins (1910–1994) and Joyce Pallot (1912–2004)

Henry Collins and Joyce Pallot (also known as Henry and Joyce Collins) were two artists who lived and worked together for over 60 years. They are best known for their work on several large-scale public concrete murals during the 1960s and 1970s, many of which remain around the UK today.

Droitwich Spa since Roman Times

1976

Henry Collins (1910–1994) and Joyce Pallot (1912–2004)

Banksy (b.1974)

Banksy has been creating satirical street art graffiti in a distinctive stencilling technique since the 1990s. His works of political and social commentary have appeared on streets, walls and bridges throughout the world.

Contemporary muralists are often commissioned to create painted murals to enhance streets and buildings across the UK. We Are Culla, for example, are based in Stoke-on-Trent and aim to alter the negative perceptions of graffiti and street art through designing and creating quality murals and painted commissions to engage businesses and communities.

One of their commissions, Bottle Ovens on End of a House in Middleport, uses a bold geometric design to echo the shape of the bottle ovens and factory buildings from the nearby Middleport Pottery. It is placed on the end of a row of terraced houses which will have housed the factory's pottery workers. The mural reflects the history and heritage of the area, whilst enhancing what was a plain end wall.

Bottle Ovens on End of a House in Middleport

2021

Florence Blanchard and We are Culla

Many contemporary artists take part in street art festivals across the UK, such as Concrete Canvas in Chelmsford, Essex.

These festivals take months of planning to find locations for the murals and bring a wide variety of street artists together to decorate walls and showcase their mural art.

Katey Goodwin, Art UK Deputy Chief Executive and Director of Community Engagement

Further reading

Lisa Brown, Post War Public Art, the modernist, 2021

Lynn Pearson, A Field Guide to Postwar Murals, Blue House Books, 2008

Lynn Pearson, Postwar Murals Database, Academia, 2015

Alan Powers et al., British Murals and Decorative Painting, 1920–1960, Rediscoveries and New Interpretation, Sansom & Co., 2013