The British figurative painter Lucian Freud (1922–2011) was well known for being the grandson of Sigmund Freud, but also for his promiscuity, having fathered numerous children with several different women (he acknowledged 14 children as his own). Although an intensely private man, Freud did not deny intimate relations between himself and other men. But what he did attempt to keep secret through the years was his concurrent love triangle with the artists Adrian Ryan and John Minton.

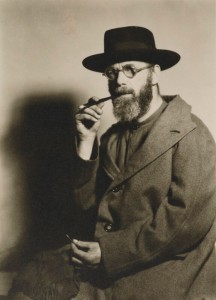

Lucian Freud

c.1945, film negative by Francis Goodman (1913–1989)

In 'Freud, Minton, Ryan: unholy trinity', a collaborative exhibition showing at Victoria Art Gallery, Bath (until 19th September 2021) and subsequently at Falmouth Art Gallery (25th September – 27th November 2021), we find the affair centre stage for the first time in an exhibition showcasing, side by side, works from the trio during that time.

Featuring over 50 paintings by all the three artists between the dates 1937 and 1957 – the period of their 'unholy trinity' – the exhibition is curated by Julian Machin, a biographer of Adrian Ryan who was friends with him from 1987 until his death in 1998. Machin notes in his exhibition essay that Ryan revealed, during an interview for his biography in 1990, the existence of a 'sexual trinity' between the three artists that began sometime during the war.

Developing their practice together during this pivotal time in their careers, having been close confidants in the pre-war London art world, the intimacy between the three artists is examined through the lens of their work.

The intensity that characterised their work reveals how painting was an outlet to express their feelings about their relationship, through metaphors and motifs.

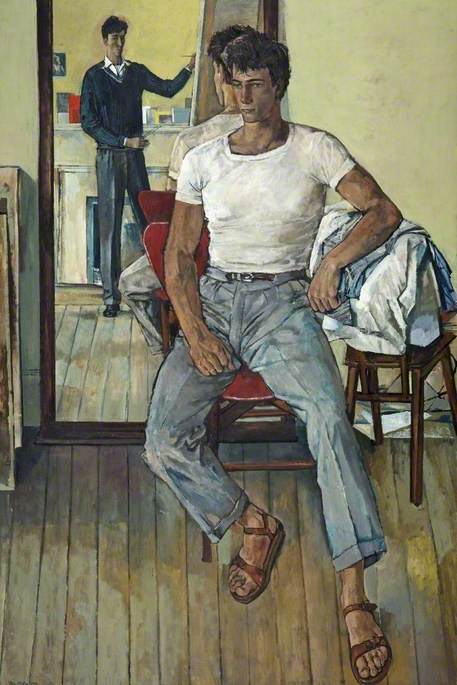

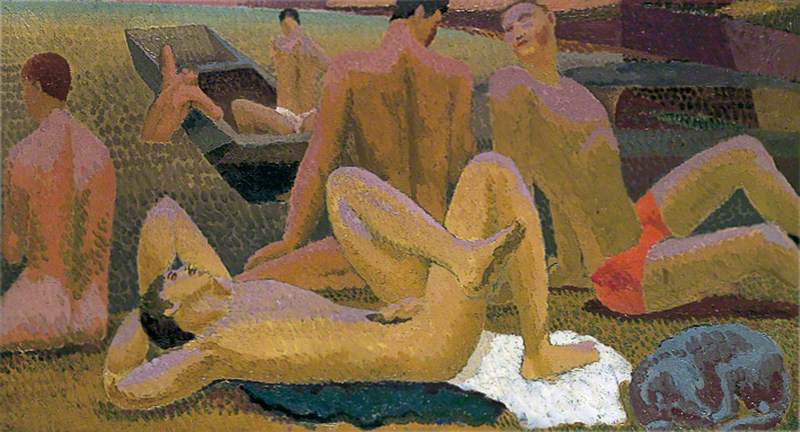

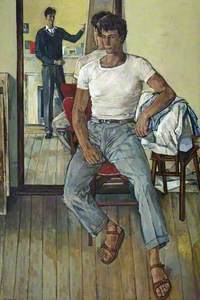

Sensuality is a key element in the exhibition, in which several works focus on the male and female body as subjects, notably seen in Minton's Painter and Model, which features models in euphemistic poses. The more exuberantly queer of the three, Minton did not shy away from direct references to his sexuality. In the relationship, too, Machin describes him as the fuel that propelled Ryan and Freud's intense love affair.

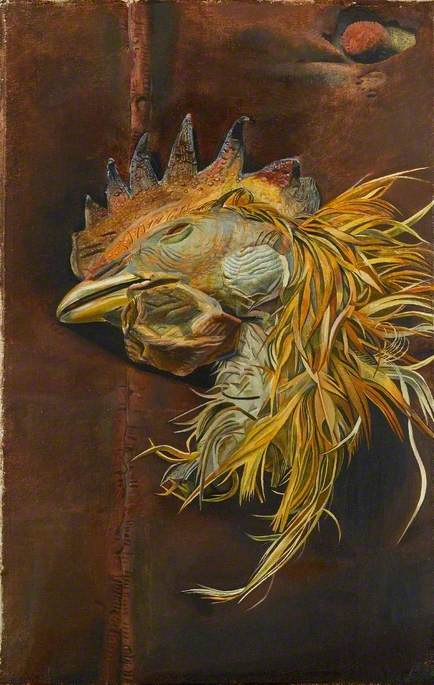

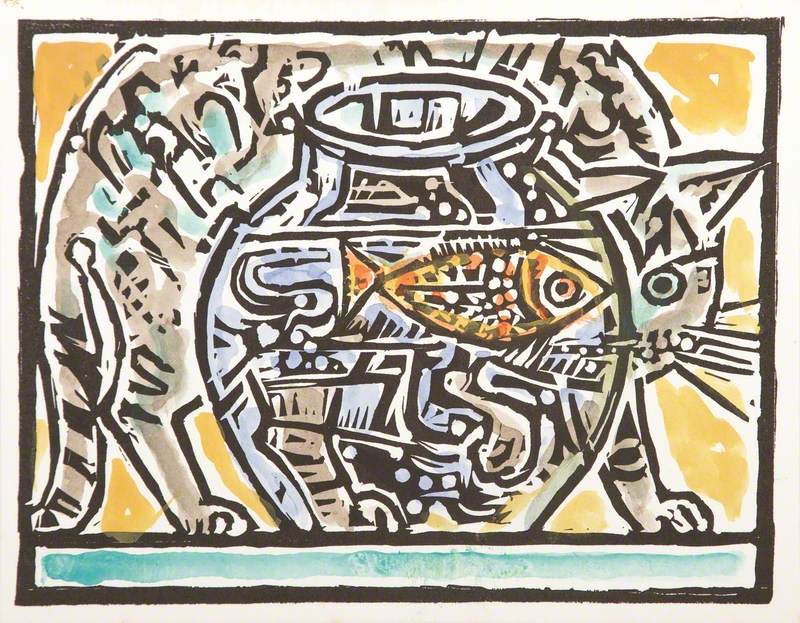

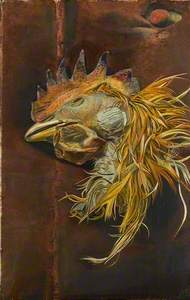

The preoccupation with the visceral amongst the trio extended beyond the human form; Freud and Ryan are revealed to have a similar fascination for the gore and rawness of animal carcasses.

Three Fish may yet be Ryan's closest hint at the trinity, the fish packed tightly and snugly together in a row. He was said to find a curiosity in the enduring quality of the animal, remarking once to Machin: 'When times change, the landscape changes and the urban scene changes, and the fashions and appearances of people change, but the fish remain the same.'

Three Fish

c.1951, oil on canvas by Adrian Ryan (1920–1998)

Created in the same year as Three Fish, Freud's Dead Cock's Head resulted from an avid interest in butchers' displays of raw meat during his visit to Dublin, which he found to be sensorily overpowering. The angle of the cock's head implies the closeness of it to the viewer, lending it an overwhelming immediacy.

Despite the influence and rise of abstraction and Pop Art in the post-war period, all three artists were collectively steadfast in rejecting these movements. They shunned fashionable abstraction in favour of figurative work – an artistic decision that would cost them personal success and recognition in the mid-century.

Nevertheless, the trinity proved highly productive, the figurative work they made imbued equal parts with intensity and melancholy. In Freud's Girl with Roses, a painting of his first wife Kitty Garland, whom he married in 1948, her eyes are bulbous, wide and penetrating – they glare off the easel. Freud focused on his subject's eyes as part of a sensory experience, engendered in the painting process by making the sitter uncomfortable with his close, intense scrutiny.

The opposite of idealised, Kitty's bug-eyed features are unflatteringly visceral. The rose she grips tightly is prominently thorny, and she exudes a glow in her outline with a nervous, buzzing energy.

Freud 'was compulsively committed to the uncompromising and relentlessly honest portrayal of what he saw', according to the exhibition's catalogue essay. Such sharpened intensity on his subject can also be detected in the portrait Head of a Girl with Red Hair, which is also featured in the exhibition.

Head of a Girl with Red Hair

c.1948, pastel on black paper by Lucian Freud (1922–2011)

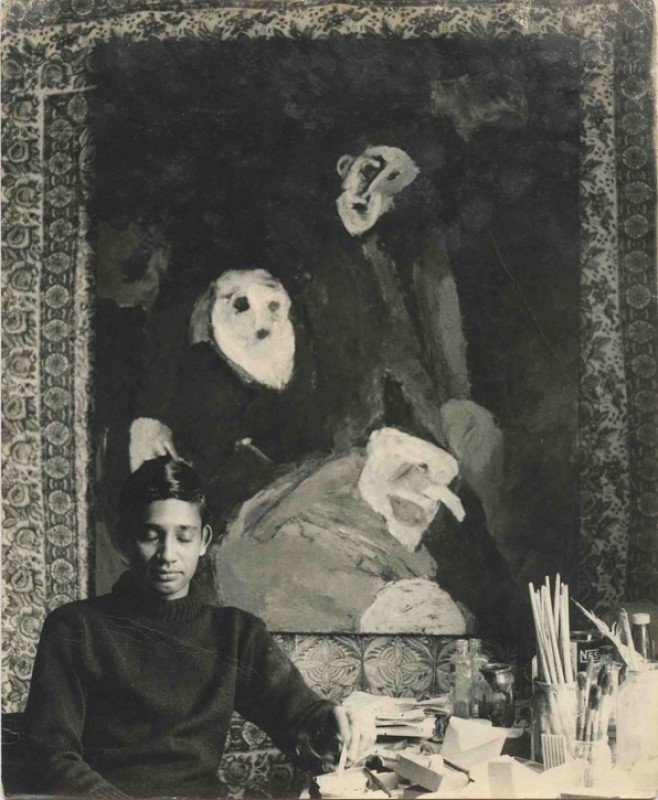

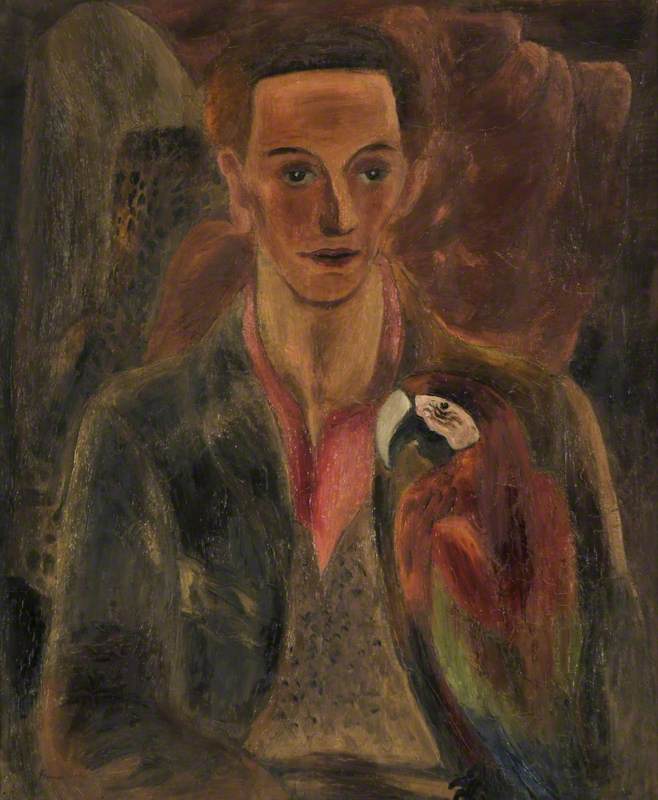

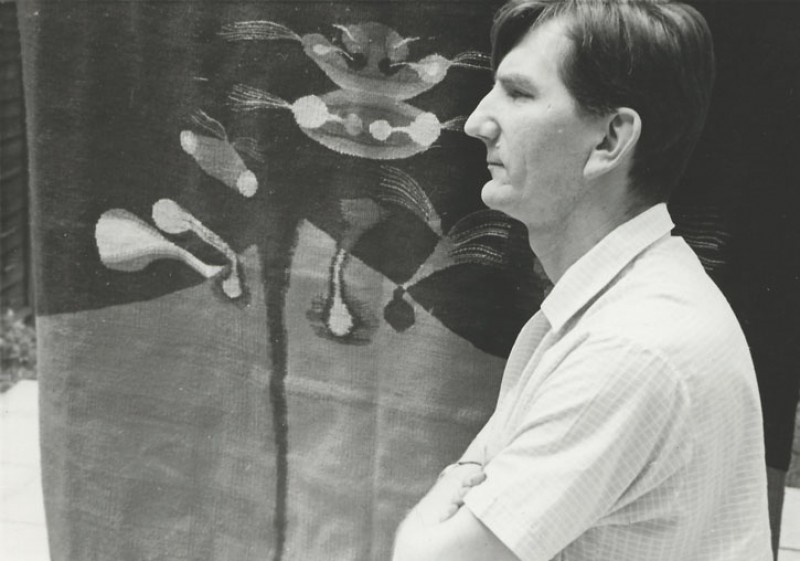

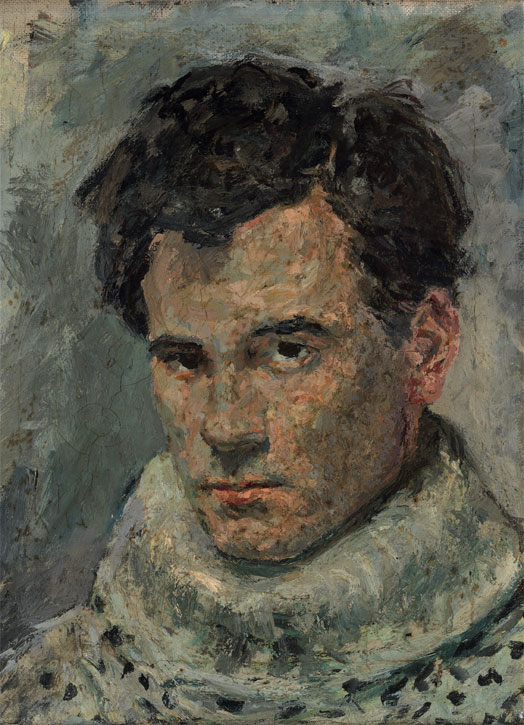

While Freud produced unflinching portrayals of others, Adrian Ryan tended towards harsh paintings of himself that bear hints of emotional self-flagellation. Ryan's upbringing was not a happy one. His self-effacing nature peaked when his mother accused him of cowardice during the war – despite his earning a commendation for his efforts.

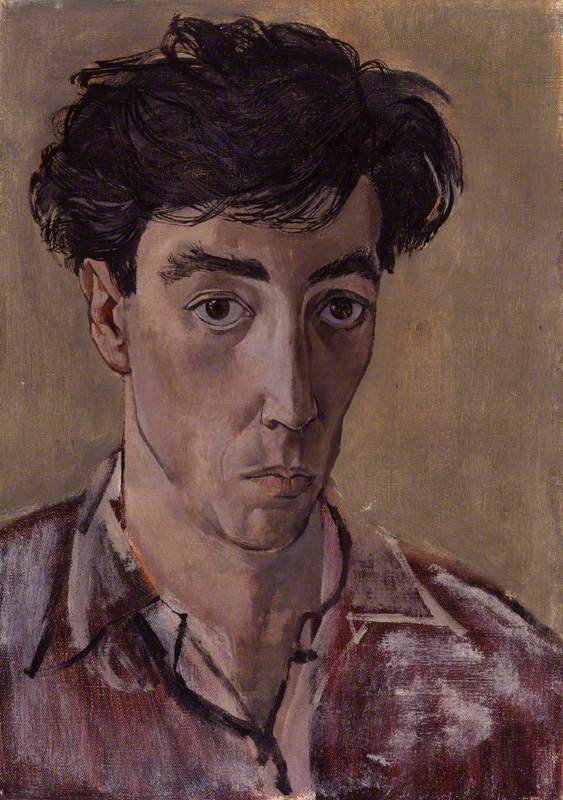

Self Portrait

1944, oil on canvas by Adrian Ryan (1920–1998)

Self Portrait was painted during this time, revealing his perennial self-doubt through the blurred background which he constantly erased and repainted, dissatisfied with how it looked. Yet he was sure of his own emotions. Aged 23, Ryan looks shy, sheepish and unsure in the portrait; he gazes up toward the viewer wistfully.

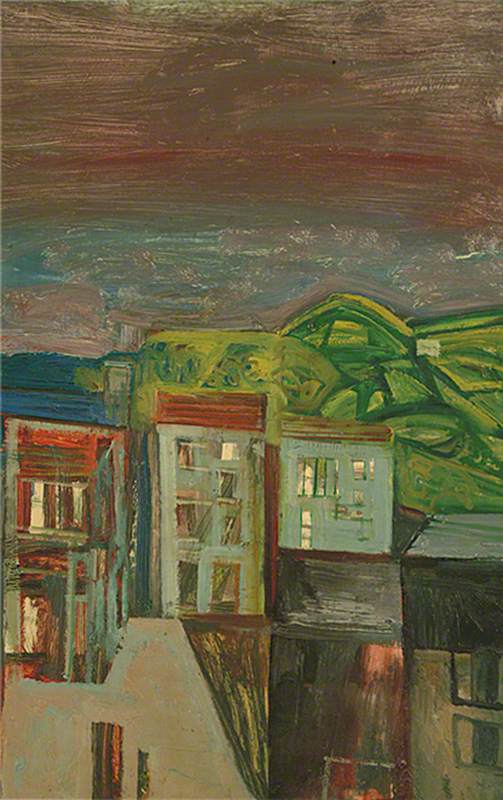

Ryan's use of a dark bluish palette, alongside his murky and manic brush strokes, is a common thread throughout his works in the exhibition. Seen collectively, they lend the viewer familiarity to a maudlin state of mind that stretches over decades and varying subjects. In the context of the trinity, Ryan's still life works such as Tite Street Interior stand in contrast to (or, indeed, complement) Freud's calculated brushstrokes that brim with precision and detail.

Tite Street Interior

1948, oil on canvas by Adrian Ryan (1920–1998)

The trinity found travel to be a key means of escape from the unhappiness of their personal and professional lives, and the three artists became heavily influenced by local scenes.

For Freud, the post-war liberation brought about an itch to leave bombed-out London. Stowing away on a fishing boat intending to get to France, Freud and fellow artist John Craxton were caught and forced off onto the Isles of Scilly. Mesmerised by the relatively more exotic flora and fauna there, he faithfully recreated them with precision.

Palm Tree is a testament to his skills as a draughtsman, detailed and meticulous just as he was to his human and animal subjects.

At times the artists veered into landscapes, which are linked by their deep sense of place and melancholy that they associated with their memories. All three depicted summer homes fondly, nostalgic for a time they were free to be themselves privately.

For Ryan this was seen in Dawn over Nelwyn: View from Myrtle Cottage. Purchased from his lover Polly's mother, Ryan spent a happy spring of 1951 there until an acrimonious split from Polly meant she refused him ownership of the cottage. Made in the aftermath of this loss, the work serves as a longing remembrance of happier times; the intimate knowledge he had of the place is seen in his meticulous tracing of the town's roofs and how the light bounced off the sea onto them. But it's tempered by the dusky twilight, coupled with an eerie emptiness. The town is devoid of human activity, still and silent.

John Minton's landscapes, on the other hand, were human-centred. Buoyant from victory, his post-war scenes were populated by the bustle of commercial activity. He painted everyman subjects seen in works such as The Hop Pickers (noting again the motif of three pickers in close proximity). These depictions brought him into wider relevance as a noted post-war scene painter.

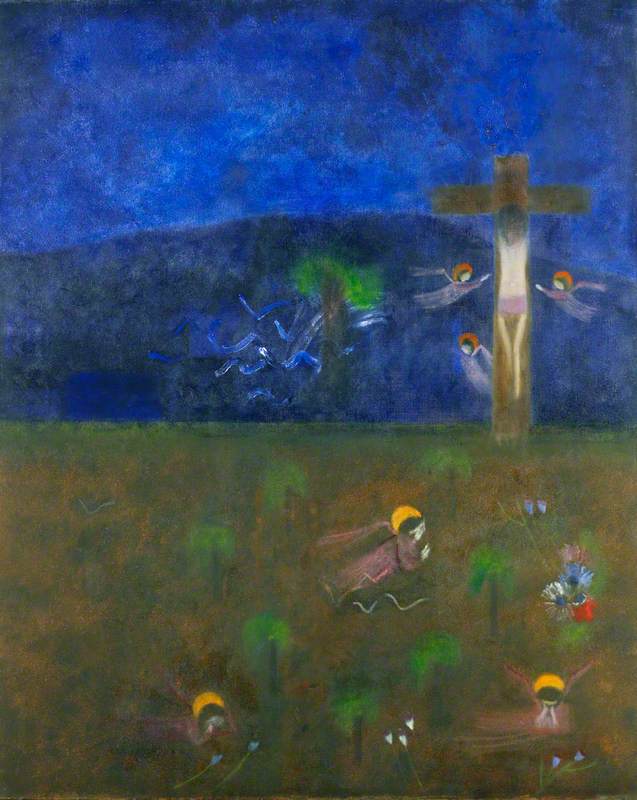

But his frustration with the rise of abstraction led him back to allegorical painting, leading him to produce a somewhat uncharacteristic painting titled The Kite (1940). The painting depicts forlorn figures in a desolate, post-apocalyptic landscape, with a kite possibly serving as a small beacon of hope out of what he saw as an abstractive, senseless nightmare.

The Kite

1940, pen & gouache on paper by John Minton (1917–1957)

With no concrete evidence that the trinity existed bar the revelations from Machin and a few individuals in the artists' social circles, the curators chose to bookend the exhibition with a filmed discussion of the artists' birth charts by the astrologer Reina James. Based on the placement of the constellations above the artists at the time of their birth, James' readings serve to spiritually cement the existence of the trinity.

Her reading reveals that Adrian was predisposed to experiencing betrayal as a new way of experiencing his childhood trauma. 'There's a great pleasure there [of] enjoying each other's company but tremendous fear [of] showing any need or fear or hunger for more intimate connection than they're able,' says James. Her assessments go some way to supporting the hypothesis that the relationship between Ryan and Freud deteriorated with the suicide of Minton in 1957, another aspect we have no true insight to. It is here that the exhibition ends.

'Unholy trinity' gives equal billing to the three artists, placing them as artistic equals, which, with the celebration of Freud whilst Ryan has faded into relative obscurity, Machin notes 'latterly, is not how fate has decreed it.' The exhibition is a visceral journey through their works, a passionate affair identified through multitudes of secrets and metaphors hidden in plain sight.

Ashley Tan, freelance writer

'Freud, Minton, Ryan: unholy trinity' is at Victoria Art Gallery in Bath until 19th September, followed by Falmouth Art Gallery from 25th September to 27th November 2021.