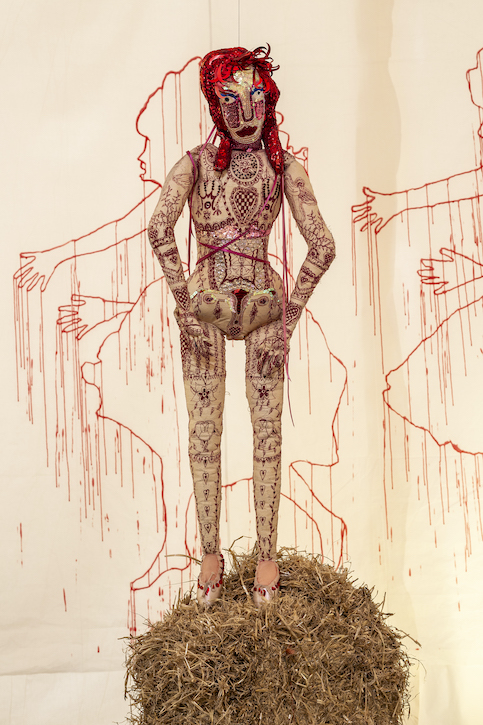

Embroidery, paintings, installations, collections of baby dolls and household ephemera, costumes, masks, films and words: the art of Delaine Le Bas (b.1965) swallows up genres and spits them out whole in a unique commentary on femininity, childhood, Romani heritage, prejudice and our relationship with nature.

Delaine Le Bas

Alongside being nominated for the Turner Prize 2024 for her exhibition 'Incipit Vita Nova' at Secession, Vienna, she currently has a large solo show at Tramway in Glasgow, 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding' – a co-commission with Glasgow International – and an upcoming exhibition 'Rags of Evidence' opening at Brighton's John Marchant Gallery in September. Together, the three exhibitions demonstrate the incredible breadth of the British Romani artist's continually evolving practice. I talk to the artist about textiles, performance and identity.

Rosemary Waugh: We often presume there to be a distinction between 'visual art' and fashion and costuming, whereas in your work it seems these distinctions don't exist. Where does your interest in clothes and costumes stem from, and how does it sit within your wider work?

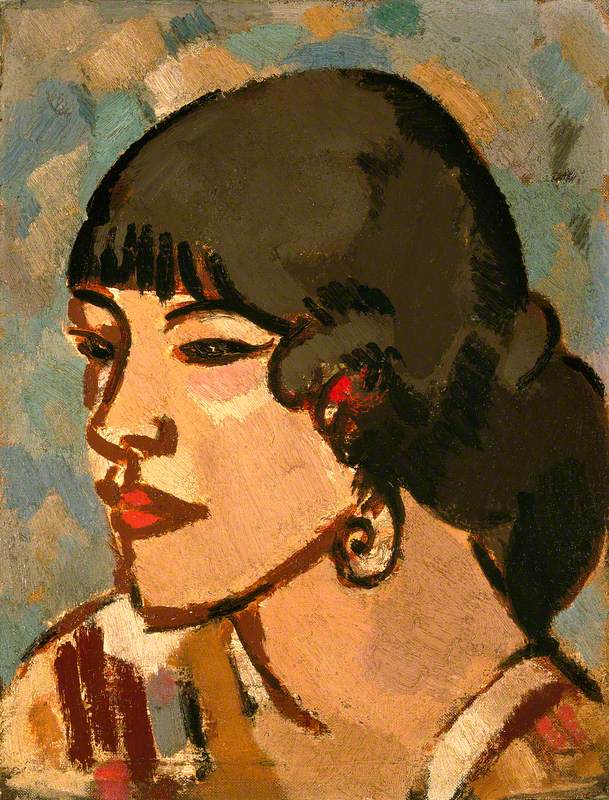

What We Don't Know Won't Hurt Us? (Self Portrait)

Delaine Le Bas (b.1965)

Delaine Le Bas: Growing up, me and my extended family didn't look like anyone else. I went to school dressed very differently, so it was just part of my everyday 'thing'. Later, I became interested in punk and was influenced by Poly Styrene of the band X-Ray Spex and the idea you could wear whatever you liked. I then went to college and studied textiles and later to Central St Martins to do an MA in Fashion and Textiles. I don't really see where things start and where they stop; I like to be able to move from one thing to another quite fluidly. Costuming is part of my clothing as well as part of my performances. I like it to all be a bit blurred.

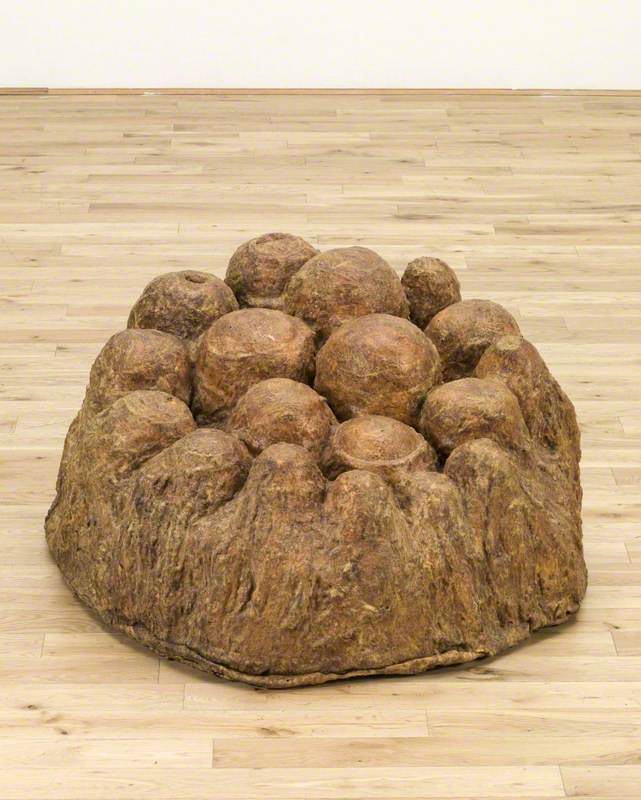

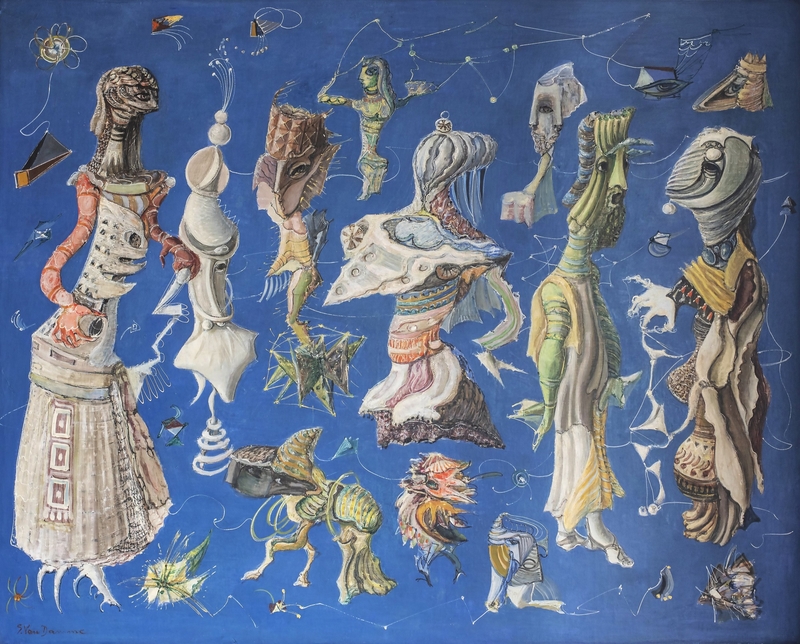

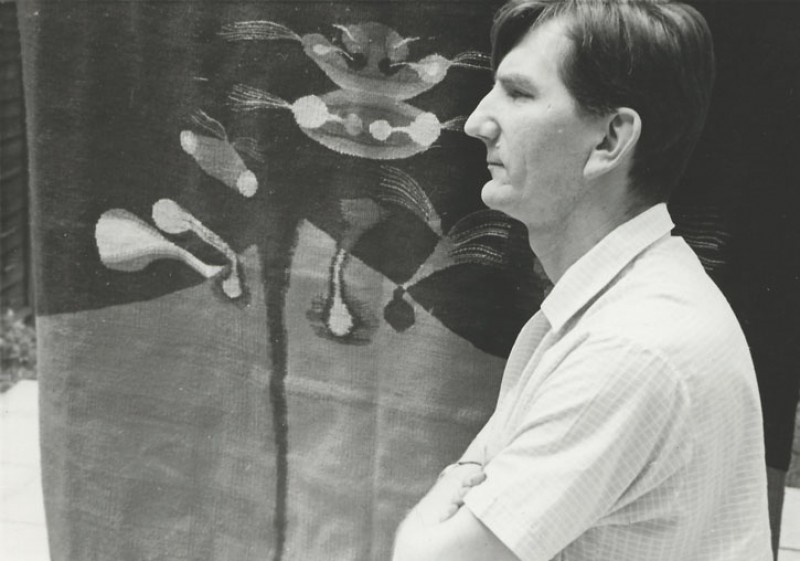

Installation view, 'Delaine Le Bas: Incipit Vita Nova', Secession, Vienna, 2023

Rosemary: You just mentioned performance, which is another part of your work – along with installation, embroidery, decoupage, sculpture, the use of words, film, painting and drawing. In every sense, you are truly multidisciplinary. How do all these different components function when placed in a traditional gallery space?

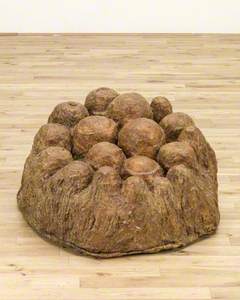

Installation view, 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding', Tramway, Glasgow, 2024

Part of Glasgow International Festival, 7th–23rd June 2024

Installation view, 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding', Tramway, Glasgow, 2024

Part of Glasgow International Festival, 7th–23rd June 2024

Delaine: I try not to think about whether my work is in a gallery, I treat it as just another space. I've worked in so many different spaces and I see every space as having potential. Historically, there were many places where people performed that don't exist anymore. All these different fairs and gatherings that once happened throughout the year have been eroded and eradicated. Part of going to those gatherings involved dressing up, not necessarily in costume but 'dressing up' in a way that meant people were, in a sense, performing.

Installation view, 'Delaine Le Bas: Incipit Vita Nova', Secession, Vienna, 2023

Rosemary: You mentioned being influenced by punk, but what were your early artistic influences?

Delaine: I studied design, not art, so a lot of what we looked at in college were things like Bauhaus and William Morris. But my first real influence was my great-uncle and the old films he showed me. The way people dressed, the music, the colours (in some of them) and the sets all had an impact. We watched things like The Wizard of Oz, The Red Shoes, Singing in the Rain, Imitation of Life and An American in Paris. He was obsessed with Veronica Lake and would do these drawings for me of women looking like Hollywood film stars with amazing hairstyles. He also did my hair for me.

Rosemary: Were there artists who influenced you later on?

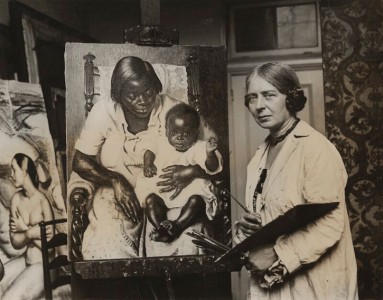

Delaine: I've often been drawn to female artists who have just made work and got on with it: people such as Paula Rego and Louise Bourgeois. For decades, they just made work for themselves, long before anyone realised what they were doing and started to take note.

Rosemary: You wrote a piece for the Whitechapel Gallery's website [linked to the artist's exhibition, 'House of Le Bas' at the gallery in 2023] in which you mentioned using a washing line when creating big paintings. Do you still do that?

Delaine: Yes. I work from my house which is quite small and there's not much space in it because I've got lots of collections – some of them inherited from my late husband [the artist Damian Le Bas] and grandmother. So almost all my big paintings are made outside and the weather influences how they turn out. I like the unpredictability: if the wind catches it, the paint goes in a different direction and then I react to that.

Installation view, 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding', Tramway, Glasgow, 2024

Part of Glasgow International Festival, 7th–23rd June 2024

Rosemary: A lot of the writing about your art focuses, understandably, on your Romani heritage. Can that perspective become reductive or limiting?

Installation view, 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding', Tramway, Glasgow, 2024

Part of Glasgow International Festival, 7th–23rd June 2024

Delaine: As human beings, we are all complex: there are so many layers to us. It's just one part of who I am, it's not my entirety. I'm very proud of what my grandmother and great-uncle managed to achieve. For them, just surviving was a miracle. My grandmother lived outside until she was 21 years old, and they lost siblings because of the way they lived. But it's difficult territory to navigate, especially when there are boundaries around even the language or words used to describe yourself. There needs to be more subtlety with these types of conversations, because it can be difficult for both the person being talked about and the person talking.

Rosemary: A complex understanding of identity links to your current exhibition at Glasgow's Tramway and its title 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding'. The numbers represent your date of birth, but I was intrigued by the word 'unfolding'. Why did you choose this word to represent the show?

Installation view, 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding', Tramway, Glasgow, 2024

Part of Glasgow International Festival, 7th–23rd June 2024

Delaine: I used the word mainly because it relates to fabric and I use so much of that. You have to unfold fabric, even if you're storing it. You unfold and refold it in different ways because otherwise it becomes weak along the fold lines, meaning unfolding is a natural thing to do with fabric. But I also feel my life is continually unfolding because, as human beings, we don't stand still. Sometimes you feel you've got to a certain point and then something else happens and you're constantly readjusting, so it seemed like a very good word to use.

Installation view, 'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding', Tramway, Glasgow, 2024

Part of Glasgow International Festival, 7th–23rd June 2024

Rosemary: Talking of 'things happening', you've recently been nominated for the Turner Prize. What effect has that had on you?

Delaine: I haven't had time to really process it. I feel really privileged to be part of such an amazing group of [nominated] artists. I'm not really allowed to say much about it all at this stage!

Rosemary: Could we end, then, with you saying a little bit about the show in Vienna which earned you the nomination?

Delaine: Yes. It was at Secession and I had the opportunity to make new work, which was fantastic. I was very influenced by the recent death of my grandmother. I had cared for her a lot and spent a lot of time at night nursing her when it was dark, and there was shadows and light playing in a particular way and the sounds were different.

Installation view, 'Delaine Le Bas: Incipit Vita Nova', Secession, Vienna, 2023

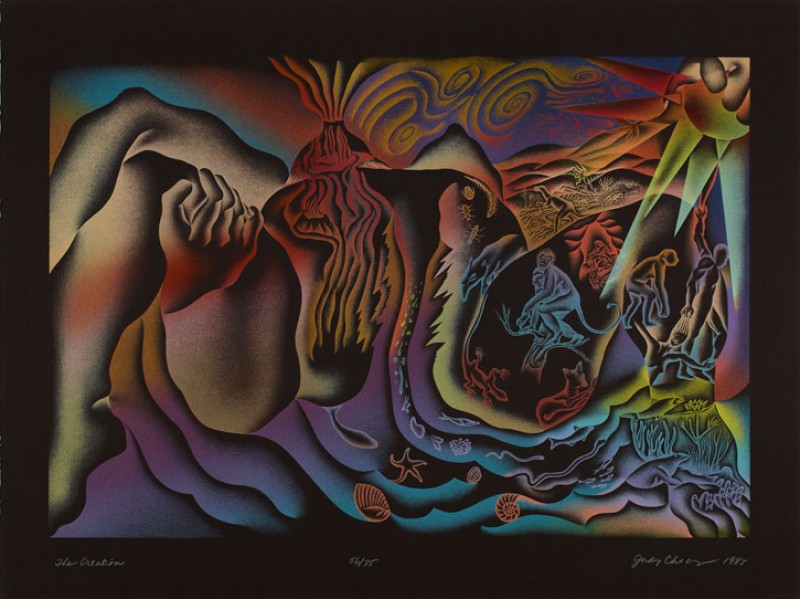

My exhibition was also on the same floor as the Beethoven Frieze by Gustav Klimt, which is a work that's all about hope, really. It goes through typhus and all the pain and suffering, but it ends with hope.

Beethoven Frieze

1902, mixed media by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), installation view, Secession, Vienna

For me, it's very important to see an artwork physically, which I was able to do with the frieze. I don't want a pair of goggles on my eyes, I want to be in front of something, really experiencing it and being in the atmosphere with other people. That's something I'm trying to do with my work as well: make the space more inclusive so anybody can really feel or smell or touch something. That's why I like fabric, it's not behind glass or in a frame. It's more free.

Rosemary Waugh, art critic and journalist

'Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding' at Tramway, Glasgow runs until 13th October 2024

'Rags of Evidence' at John Marchant Gallery, Brighton is on from 7th September to 13th October 2024

The Turner Prize 2024 exhibition at Tate Britain is on from 25th September to 16th February 2024

The exhibition 'The Archipelago on Fire' is on at Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix, London from 4th October 2024 – 25th January 2025 (opening reception on 3rd October)

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation