While the ocean covers over 70 per cent of our planet's surface, only five per cent of it has been topographically imaged or explored. Humans have feared and fantasised about monstrous sea creatures for millennia.

Perseus and Andromeda

1735–1740, oil on canvas by Charles André van Loo (1705–1765)

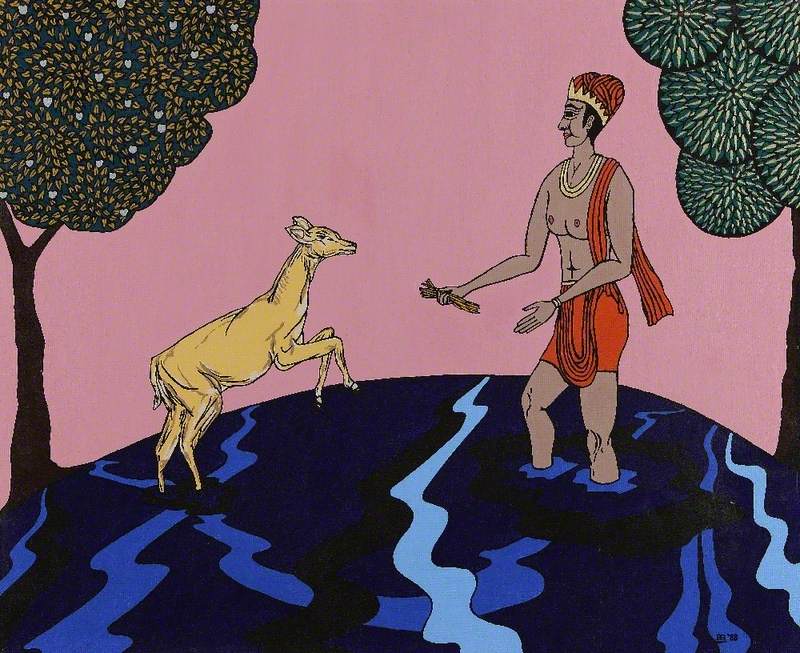

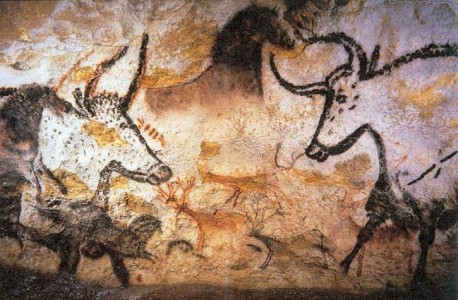

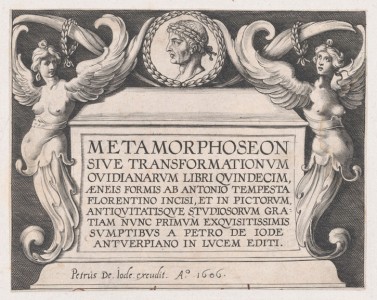

From enchanting sirens to the gargantuan Kraken or biblical Leviathan, tales of underwater beasts from around the world have always found their way into art history through one medium or another. Some of the first modern atlases included illustrations of the bizarre or macabre monsters ships might have stumbled upon as they crossed the world's waters, while later depictions are more open to interpretation. By tapping into ancient traditions and folklore, paintings can explore how some of our deepest fears and anxieties may be symbolised.

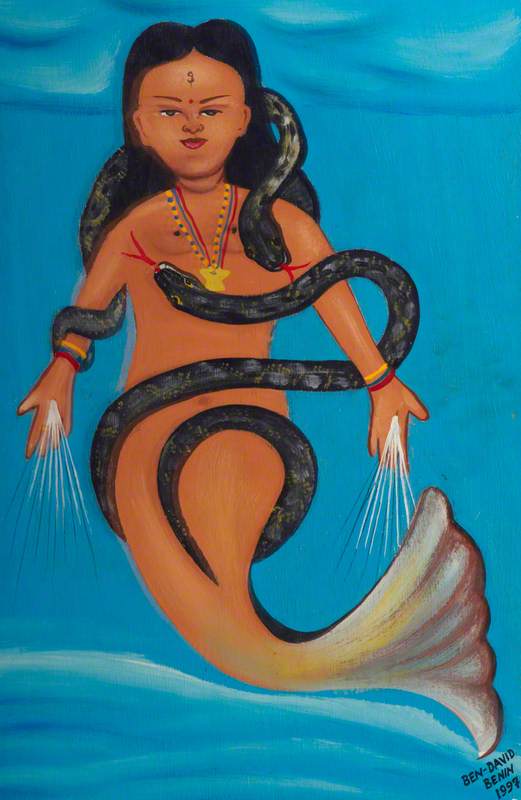

Medieval beliefs, going as far back as the first century, held that every land animal had its own marine counterpart or equivalent. Thanks to the constant shift and movement of waves, it was also believed that animals could combine and become hybrids.

The Roman author Pliny the elder's Natural History is partly responsible for this theory. He also described mythological creatures such as the headless men known as blemmyes, the dog-headed people known as cynocephalus and sciapods, who had a single, large foot extending from their torso. Woodcut illustrations of them were also included in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), one of the first printed books to integrate text with illustrations.

Sea Monster (Das Meerwunder)

c.1498, engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), the godson of Anton Koberger, publisher of the Nuremberg Chronicle, created an engraving which also features a monstrous being as its subject matter. The Sea Monster depicts a naked woman being taken by a merman (the half-man, half-fish counterpart of the mermaid). Other naked women are shown scrambling to the shore, while a gentleman waves his arms in distress. The ambiguity of the captured woman's expression as she looks back suggests she might actually be willing to go with the merman, rather than resisting abduction.

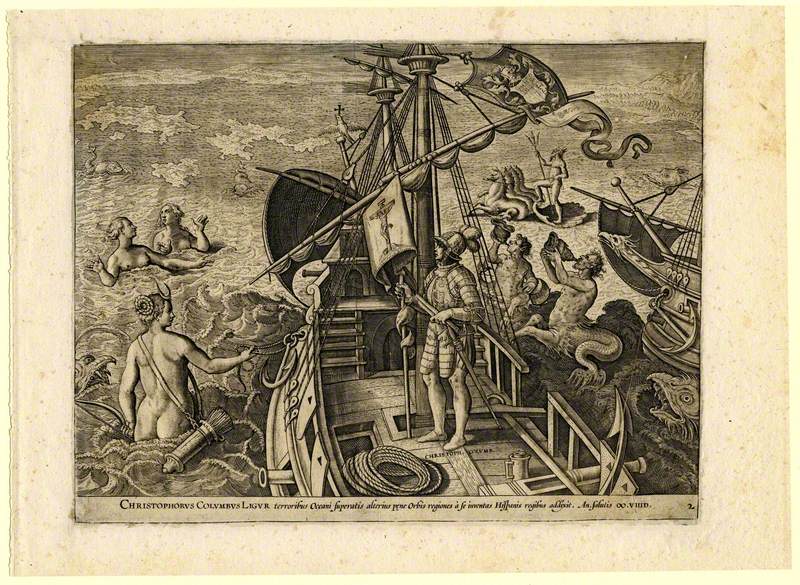

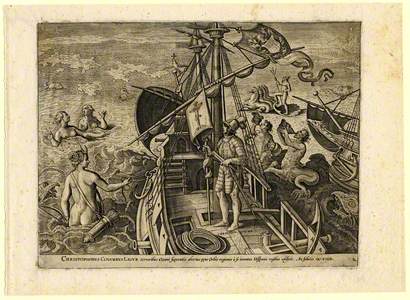

The allure of ocean inhabitants was not felt by Christopher Columbus, who was particularly wary of encountering sea monsters on his many voyages. When sailing close to Haiti in 1493, he reportedly caught sight of three mermaids who were 'not as pretty as they are depicted, for somehow in the face they look like men.' It is now understood that what Columbus actually saw were manatees.

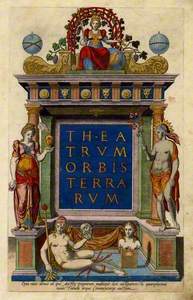

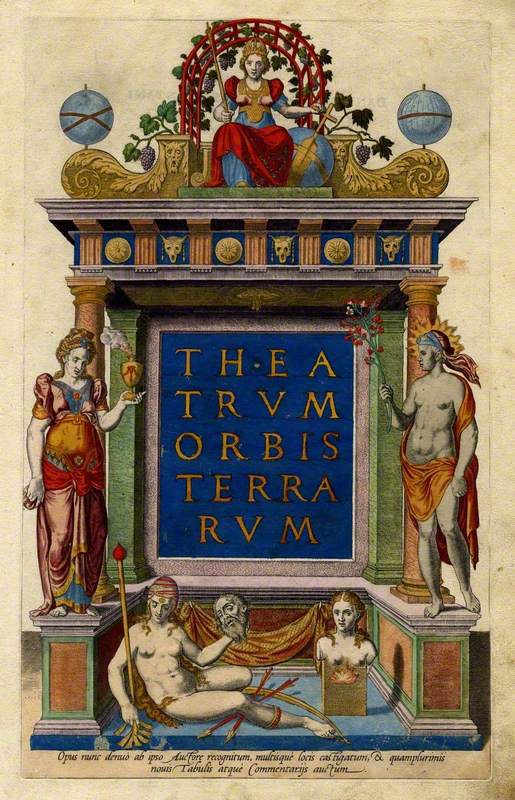

Title Page of ‘Theatrum Orbis Terrarum’

1570–1579

Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598)

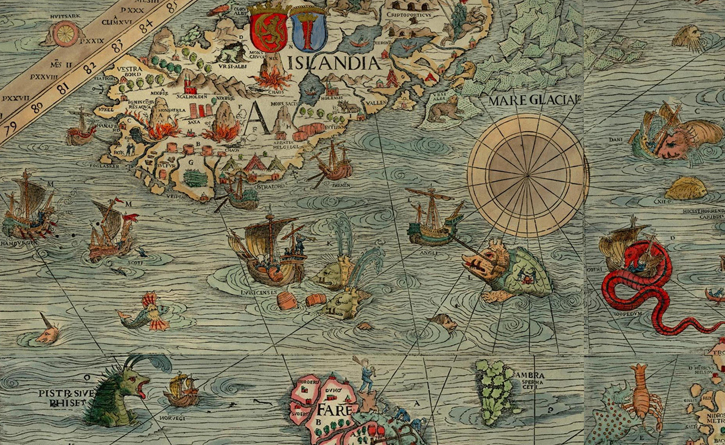

A number of Renaissance maps featuring illustrations of sea monsters were reproduced in Abraham Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of 1570. Descriptions of the creatures could often be found printed on the other side of the maps. On an early map of Iceland copied from the Swedish writer Olaus Magnus, they range from being 'the greatest kind of Whales, which seldome sheweth itselfe; it is more like a little island, than a fish' to a 'horrible sea monster, swallowing the black seal, in one bitte.'

Detail of 'Carta Marina'

1539, parchment map by Olaus Magnus (1490–1557)

Speaking on a podcast about the topic, the author of Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, Chet van Duzer, said that: 'To our eyes, almost all of the sea monsters on all of these maps seem quite whimsical, but in fact, a lot of them were taken from what the cartographers viewed as scientific, authoritative books.'

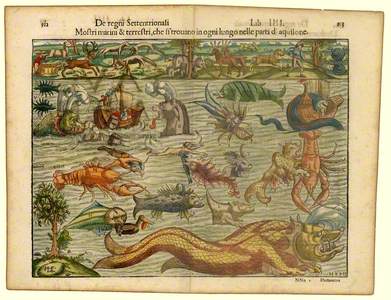

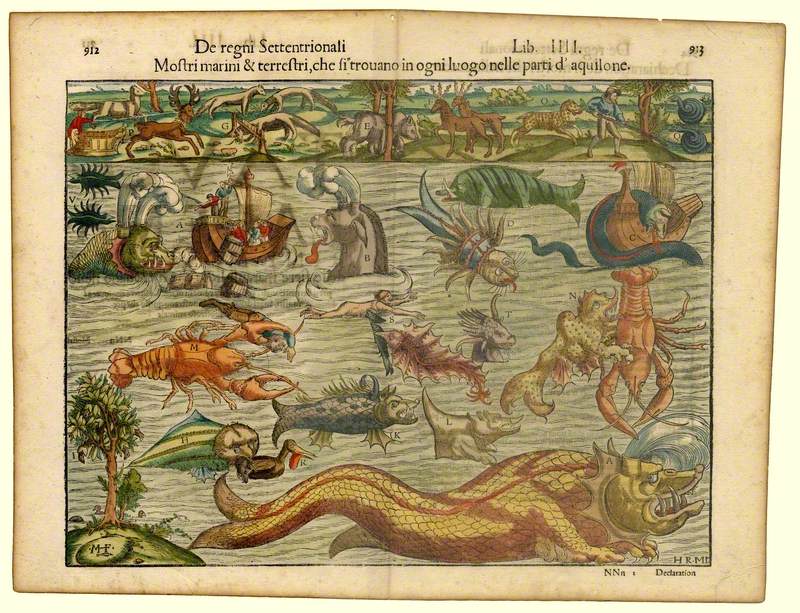

Mostri Marini et Terrestri... (Monsters of Sea and Land...)

1550

Sebastian Münster (1488–1552)

Magnus' writing on such monsters would go on to inspire Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia, considered to be one of the most popular books of the sixteenth century. The illustration Mostri Marini et Terrestri... (Monsters of Sea and Land...) shows a miscellany of monsters which terrified generations of seafarers and landlubbers alike.

Although sea monsters began to disappear from maps by the end of the seventeenth century, they were still a strong presence in fine art. Advancements in technology may have provided sailors and scientists with a greater understanding of navigation and marine biology respectively, but they did not entirely remove the mystery of underwater creatures.

Painted towards the end of his life, J. M. W. Turner's Sunrise with Sea Monsters is thought to be related to a series of paintings of whaling scenes he made during the 1840s. The right-hand side of the painting glows brightly with rich tones of yellow, making the bottom of the painting particularly murky and grey. According to its gallery panel at Tate, 'the obscure pink shape at the lower centre of the canvas probably depicts fish'. Though this is likely to be true, the unfinished painting's label draws attention to the enigmatic presence of eyes (and possibly a monstrous mouth) gazing out from the canvas.

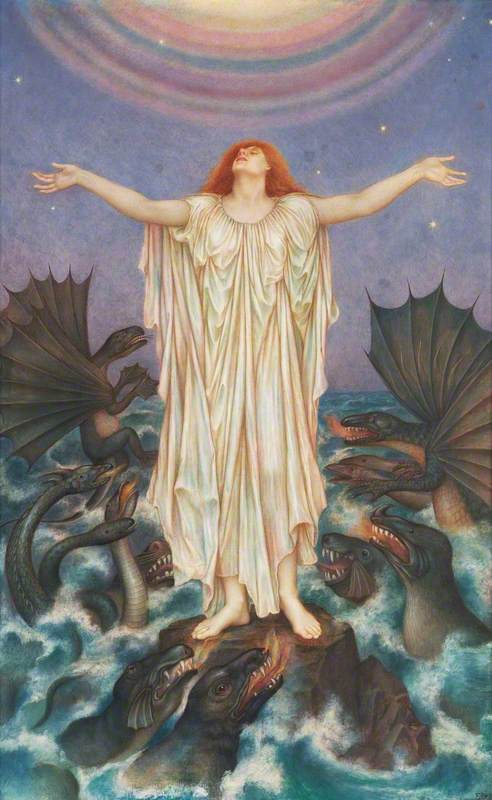

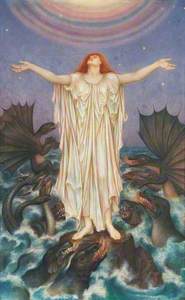

During the twentieth century, the portrayal of sea creatures in art took on greater allegorical significance. In Evelyn De Morgan's SOS, a female figure is shown standing upon a tiny rock surrounded by attacking beasts. She is facing upwards to the heavens with her arms outstretched, completely unaffected by the stormy waters or sea serpents, some of which even resemble dragons. In response to the horrors of the First World War, De Morgan painted this central figure as a symbol of hope and peace rising above the dangers of brutality.

Almost 20 years later, the artist Ithell Colquhoun became affiliated with the Surrealists upon moving to Paris in 1931. Colquhoun's 1938 oil painting Scylla is named after an ancient Greek sea monster which, along with its counterpart Charybdis, fed on passing sailors. On the one hand, it is a conventional seascape showing a ship approaching two rocks and a patch of seaweed or coral, while on the other it shows a pair of phallic-looking thighs with pubic hair at the base. When explaining the painting, Colquhoun said: 'It was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath… it is thus a pictorial pun, or double-image.' In this 'double-image', seduction lies at the heart of both the Greek myth and Colquhoun's Surrealist allusion to it.

A Remarkable Occurrence in the Life of Brook Watson

1778

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) (copy of)

Depictions of sea creatures may no longer appear in art the way they used to, but that does not mean they have completely disappeared from the collective consciousness. Perhaps we should look at the enduring legacy (and countless sequels or remakes) of films like Godzilla and Jaws. Aside from its iconic score and critical acclaim, the impact of Jaws following its release in 1975 was particularly detrimental to the public perception of sharks and the need for their protection, as well as causing reductions in beach attendance that year. More recent incarnations have ranged from the award-winning The Shape of Water to the widely lampooned Mega Shark series.

We still see the term 'sea monster' being applied to anything remotely unusual washing up on our shores. In 2017, The Independent reported that a 'mysterious giant sea monster [was] found off the coast of Indonesia.' This was only a year after a 'hideous 13-foot beast was found on Bonfil Beach in Acapulco, Mexico', as described by the Metro. It was also not long ago, in 2013, that a giant squid and 16-foot megamouth shark were captured on film (in their native habitats) for the first time.

A 60-foot fin whale washed up, and later died, on a nearby beach during the installation of the 'Monsters of the Deep' exhibition at the National Maritime Museum Cornwall earlier this year. Compared to our ancestors, we have seemingly mastered the seas, but with so much of our oceans yet undiscovered, the question of what lies beneath remains as enthralling and uncanny as always.

'Monsters of the Deep' runs at the National Maritime Museum Cornwall until January 2022.

Victoria Rodrigues O’Donnell, Museum Assistant at the Fashion and Textile Museum and freelance writer